My favourite place isn’t real and that’s why it’s called a virtual world. It is a place that is far away from real life. Headphones on, volume up high. I can screen everything out when I’m inside a game.

You look as if you’re just sitting there, but it feels like you’re actually leaving your body where it is and setting your mind free in a completely different world. A place where bad stuff only happens to the people on the screen.

Best of all, you can’t hear the real-life shouting.

I take off my headphones and listen. There are no raised voices, no slamming doors, so I get up to go to the bathroom.

Everything is quiet, as if I’m completely alone. I don’t feel scared, I like the silence. I like it better than the sound of adults fighting.

The door opposite the bathroom is open a little and I hear a noise coming from behind it. A sort of puffing, scratching sound.

I take a couple of steps closer and peer through the crack.

For a moment, it feels like I’m still in the game world. Where things aren’t real, where nothing that’s in front of your eyes makes any sense.

Before I can stop it, my breath catches in my throat. My hand flies up to my mouth but it’s too late. The gasp is already out and I know I have been heard.

I turn to run, but I hear shouting and I feel a hand clamp down on my shoulder.

‘I won’t tell,’ I cry out. ‘I promise I won’t tell.’

My teacher, Mrs Booth, speaks to us a lot in class about secrets. She always says the same thing, but does it in lots of different ways.

Last week she said, ‘Some secrets are fun and safe to keep. Like, if your dad is going to throw a surprise party for your mum, for instance.’ I looked over at Matthew Brown, who hasn’t even got a mum. ‘You wouldn’t want to tell a secret like that, as it would spoil the surprise.’

The class started to buzz with everyone telling their own stories of good, safe secrets, but then Mrs Booth clapped her hands once and started to count, ‘ONE, TWO…’

The rule is, if she gets to three and we’re still noisy, we might have to forfeit our break time.

So everyone stopped talking right away and the classroom was so quiet you could hear a pin drop. Except that’s just a saying because it’s virtually impossible to hear a pin drop. You’d have to have what’s called ultrasonic hearing, which I’d like but haven’t got.

‘But we have to remember that some secrets are not good to keep,’ Mrs Booth continued. ‘Some secrets are not safe to keep. If something makes you sad or afraid, or if you, or someone else, could get hurt by keeping a secret, then what should you do?’

‘Tell a trusted adult,’ we all say, in unison.

Despite what Mrs Booth says, I used to think that secrets were mostly exciting, something to look forward to.

I used to think that telling a secret, at the right time, was a joyful thing to do. Like ages ago, when Dad surprised Mum with her new car and she cried and hugged us both and didn’t get her frowny face for days.

But now I know that there are some secrets that can lie on your chest like a sheet of lead, or seethe at the bottom of your stomach like a knot of poisonous snakes.

I could get top marks in literacy if I wrote a story like that, but it doesn’t feel as good when it happens to you in real life.

There’s a sort of secret that grows bigger and bigger in your mind like a tumour and it stops you feeling any happiness at all.

Mrs Booth doesn’t realise that if you tell a trusted adult a big enough secret, it can get you into serious trouble.

Worst of all, telling a secret like that can hurt the people you love the most.

‘Be a good boy for Auntie Alice,’ Louise says, and gently pushes my reluctant nephew towards me.

She hands me an overstuffed plastic sack and places Archie’s school bag and coat behind the door.

It has been precisely five days since my sister deposited the poor kid on my doorstep for an impromptu overnight stay. It seems to be happening more and more.

At least this time it’s just for the evening, I console myself.

‘It’s boring here.’ Archie plants his feet and folds his arms. ‘There’s never anything to do.’

I’m the first to admit, I haven’t anything in the flat that would be remotely interesting to an eight-year-old. Apart from Magnus, that is, my big white tom, who detests Archie with a vengeance.

‘I’m sorry, poppet,’ Louise tells him, and ruffles his hair. She looks at me and pulls her lips and eyes into a squinty face. ‘Sorry he’s here again. His Xbox is in the bag, so he shouldn’t be too much trouble.’

Her phone beeps and she reads the text message, staring at the screen. Looking up at last, she gives me a tight smile and heads for the door.

‘Hang on, when are you picking him up?’

‘I’ll be back soon as I can get away from the meeting. It shouldn’t be too long after nine.’ She backtracks a few steps. ‘That’s all right, isn’t it?’

I brush down the front of my old grey fleece. It must be obvious I’m not going anywhere, but that’s hardly the point.

Despite the fact that she’s been at work all day, my sister’s make-up looks fresh, and she’s wearing tailored black trousers with high heels and a stylish mixed-tweed jacket. Her perfume fills the hallway, a fusion of sharp citrus notes softened by delicate florals.

Louise is the kind of woman who wears a different perfume on each day of the week. Not for her a signature scent.

There was a time I wore my Miss Dior fragrance like a piece of essential clothing. Wrapped myself every day in its comforting cloak of Italian mandarin, jasmine and patchouli.

When I wore it, I walked a little taller, spoke a little easier… I thought then that the scent helped to show others who I was, when in actual fact it became clear that it merely helped to cover up the fault line I hadn’t yet recognised in myself.

Too shallow, too impulsive, too shy, too selfish.

What I did to Jack proves it beyond doubt.

Louise is staring at me.

‘Where is it you’re going again?’ I say vaguely. I can’t remember if she’s actually told me or not.

‘Just a last-minute work thing,’ she says briskly. ‘Tedious but necessary, I’m afraid.’

Three months ago, Louise was promoted to the position of senior marketing manager at the Nottingham-based PR company she’s worked at for the last three years. At the time, she hinted she’d benefited from a very good salary hike, but I’ve noticed they now seem to expect a great deal more of her. Over recent weeks, there have been frequent late evenings and even the odd overnight stay in London.

It doesn’t help matters that Darren, Louise’s husband and Archie’s stepdad, also works very long hours.

Consequently, when Louise finds herself in a childcare fix with Archie, I’m usually her first port of call. I’m happy to help out, of course. I’d like to do more, if only it didn’t take so much out of me.

‘They ought to make allowances at work; they know you’ve got a child.’ I look at Archie’s glum face. ‘It’s hardly fair, just landing stuff on you like this.’

Louise gives a mirthless laugh.

‘Welcome to my world. I don’t mean to be unkind, but we don’t all get to watch daytime TV and stare out of the window for hours on end at some bloke on the tram we fancy, you know.’ She ruffles Archie’s hair as she heads for the door again. ‘See you soon, pudding.’

I swallow hard but say nothing. Louise has always engaged her tongue before her brain, but I wish now I’d never told her about my man on the tram.

I wouldn’t have thought it possible to feel a connection with someone you’ve never met, but that’s what has happened. It became harder to keep it to myself, so one day I told my sister about him in passing. Louise being Louise, she wanted the lowdown on him, of course. But there was very little to tell, although the date has seared itself into my memory.

Friday 26 February. It was the first time I saw him and a day that also happened to be my thirtieth birthday.

I was standing right by the front window, opening my single birthday card, from my sister. I set it on the windowsill, its bright metallic greeting and colours incongruous against the scudding grey sky.

Sounds dramatic, but the bleak outlook from the window seemed to pretty much sum up how my day, and most probably my life, was likely to pan out, and I’d already started to turn away when I happened to glance down to street level.

The 8.16 tram had just arrived at the busy hub that sat right outside my apartment block.

This was just a regular street when Mum first bought the flat; not a busy high street dotted with shops, not a quiet back road with residential parking only, but somewhere in between mainly used by traffic rather than people.

Before she got too ill, she would sit by the window in her nightie and slippers, watching the starlings and sparrows that perched on the rooftops of the houses across the road. When they flew past, she’d press her fingertips to the glass and get this expression of longing on her face that made me look away.

But since the city council’s much-lauded tram scheme was completed, the road and the stretch outside the apartment block have been transformed into a buzzing hive of activity at all hours of the day. I don’t see Mum’s birds as much now.

That morning, as usual, there were so many different faces and moving bodies to watch. Everyone seemed lost in their thoughts and plans for the day ahead. I found it fascinating and comforting, watching others.

Popular advice online for single people with few friends is to join clubs, walk a dog, do their food shopping at the same time every evening, I assume in the hope of casing the aisles to spot a potential suitable mate who is perhaps browsing the cook-chill meals or queuing at the deli counter.

That may all work splendidly. I wouldn’t know, I haven’t tried it. What I have discovered, however, is that it’s sometimes surprising how little it takes to make one feel a bit less lonely.

I turned back to the window again and watched the numerous passengers boarding and alighting. It was done as nothing more than a welcome distraction from the empty day that stretched out endlessly in front of me.

A few seconds before the tram pulled away, passengers rushed down the aisle to get a seat and my eyes were drawn to a pocket of stillness in the middle of the second carriage… to him.

He sat there amongst the chaos, all calm and together, fully absorbed in a book. I reached for Mum’s small bird-spotting binoculars I’d not yet had the heart to move and twisted the lenses to focus in on the tram window.

My breath caught in my throat when the striking cover of The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway filled the viewer. It was the exact same edition as the slim volume I had in my bedside drawer. The one that had remained my favourite book of all time after I first read it at school.

It felt like some kind of a sign. At that point, I hadn’t even realised his physical resemblance to Jack.

In that moment, if I’d known the extent that seeing him would rattle me and unearth the memories I’d worked so hard to bury, I’d have turned away.

But I didn’t turn away. I couldn’t.

Some time ago, I read a convincing article in a magazine about cosmic ordering. It gave examples of celebrities who subscribed to this method of thinking and had subsequently applied it to their lives with great success. I spent the months leading up to my thirtieth birthday silently beseeching the universe to send me a sign.

The morning of my thirtieth birthday, I thought that maybe, just maybe, this was it.

‘Hello, earth to Alice, you still with us?’ Louise’s glossy red manicured fingernails wiggle in front of my eyes.

‘Yes.’ I snap back to attention. ‘Sorry.’

‘See you later, then…’ She turns before stepping out of the door and onto the communal landing. ‘If I don’t break my neck going back downstairs, that is. I don’t know how you stick it here. The lifts are never working and the foyer always looks in need of a good clean. My colleague has just moved to a nice new flat in Cinderhill and it’s immaculately maintained.’

She’s exaggerating. This is not the poshest apartment block in town, but it’s far from the worst. The valuations of the flats here have really shot up in the last couple of years.

We’re no longer stuck on the outskirts of the city at the mercy of a scant and unreliable bus service. It’s just a fifteen-minute tram ride into town and there are plenty of young professional buyers with good salaries that it seems to suit perfectly.

When Mum became ill and I stopped work, we sold the family home to buy a more manageable place and to pay for regular home help, which wasn’t available on the NHS.

Mum hated it at first, missed her garden terribly, but I quickly discovered I rather liked apartment living. The way that up here you feel sort of safely tucked away from the street and from other people.

Although when Mum was still alive, her companionship made it a cosier place that felt more like home. I didn’t realise how empty and soulless the apartment would feel without her.

I close and lock the door behind Louise and walk back into the lounge. A sullen Archie flops down on the sofa and swings his legs up.

‘Just slip your shoes off, please, Archie,’ I say lightly.

With the opposite foot, he forces each shoe off, scattering small lumps of dried mud over the carpet.

‘You might want to take your fleece off too,’ I suggest.

I’m terrible for feeling the cold and I know the flat is too warm for most people’s tastes.

‘I’m OK, thanks, Auntie Alice.’ He zips up the fleece as though I might tear it off him. ‘Can you set up my Xbox?’

‘Please,’ I chide him.

‘Please.’

I suppose that’s my planned soap-viewing scuppered for the evening. Thank goodness for catch-up TV.

I pick up his shoes and head for the kitchen.

‘What’s that noise?’ Archie says, cocking his head and looking up at the ceiling.

‘Just upstairs. They can be noisy sometimes.’

‘It sounds as though someone is throwing furniture around.’ Archie frowns.

‘I’ll sort your game out in five minutes. I’ll put your tea on first,’ I call distractedly as I leave the room.

‘Not hungry,’ Archie shouts back just as I turn on the oven. ‘Mum bought me a McDonald’s on the way here.’

I turn the oven off again with a sigh. I bought some healthy breaded chicken pieces especially for Archie. Not much use to me, as a vegetarian.

More worrying is the fact that my nephew is piling on weight. It’s logical to assume that if I’ve noticed, surely Louise must have done too. I know only too well how cruel other kids can be about that sort of thing.

As I start to fill the kettle, a terrible yowling noise comes from the lounge.

I drop the kettle in the sink and tear into the other room.

‘Stop it!’

Archie releases Magnus from a bear hug and the cat scoots away.

‘I only wanted to cuddle him.’ He looks upset. ‘I want him to be my friend.’

‘You can’t force animals to like you, Archie,’ I explain. ‘You have to relax around them so they learn to trust you.’

‘I always do the wrong thing.’ He sighs and flops back onto the sofa again. ‘I’m just a stupid fat lump.’

‘Hey! I don’t want to hear you talking that way about yourself. Has someone called you that?’

‘No, but that’s what they all think.’ He shrugs and looks down. ‘I’m bored.’

I take a deep breath and try to look at it from his point of view. He’s had his evening plans ruined just as I have.

‘Look, let’s not start our time together like this. I’ll set your Xbox up right now on one condition.’

He raises an eyebrow in anticipation.

‘Are we friends?’ I say, beseechingly.

Archie gives me a half-hearted high five and I set about sorting out the tangle of wires, trying to work out what goes where.

In the end, the struggle is worth it… almost. For the next two hours at least, Archie doesn’t complain about being bored.

Instead he is engrossed in yet another virtual world that has been designed for streetwise teenagers over the age of fifteen, most certainly not for impressionable eight-year-old boys.

I really need to point out the age classification to Louise. She leads such a busy life and probably hasn’t realised that most of the games in his carrier bag have an age restriction.

Archie reluctantly pauses the game so he can visit the bathroom. It’s scary, how rapt he becomes while playing.

I sit for a moment, relishing the silence.

My eyes are drawn towards the window. I don’t feel the need to draw the curtains, being on the third floor. It’s another benefit of apartment living, having nobody overlooking me.

The tram stop below is well illuminated and the light permeates up, giving a soft glow, so it’s never really fully dark outside. I find that reassuring rather than irritating.

The day after I first spotted my man on the tram, I impulsively pushed the tiny square table from the kitchen over to the front room window. I decided I’d now start each day by taking my morning coffee and toast there, eating my breakfast while I listened to the morning show on BBC Radio Nottingham.

That change, although slight and seemingly insignificant, seemed a fitting way to begin my thirty-first year. Any change was better than nothing.

And after that, every weekday morning, on the 8.16 tram that I knew terminated at Old Market Square, he was there. Always sitting in the exact same kerbside seat.

I couldn’t see much detail up here on the third floor, yet it was still close enough to garner an impression of him. Such as how his short brown hair was shot through with gold when the weak sun shone through the glass.

In some ways, he looked nothing like Jack. It was more to do with his mannerisms, the way he held himself. He had a pale complexion and he always looked clean-shaven. His outerwear seemed to alternate between an unremarkable beige raincoat and a more casual black Puffa jacket, which I noticed he would don on the days the temperature dropped a little.

He seemed to gravitate from reading to staring blankly out of the window. Increasingly, as the tram slowed each morning, he’d look down and swipe rapidly through his brightly lit phone. Often he seemed quite absorbed in tapping away.

He always looked so… I don’t know, lost, I suppose.

There was something about him that touched a part of me I kept well hidden from everyone. I didn’t always acknowledge it, even to myself.

Such observations about someone you’ve never actually met sound crazy, I know. I’m just saying that’s how it was at first.

Archie reappears, back from his visit to the bathroom.

‘Only ten more minutes.’ I check my watch as he slumps into the chair without answering.

‘Die! Die!’ he screams, pummelling the console.

I wish I could build a bit of rapport with my nephew.

Despite trying to entice him – unsuccessfully – to play a board game or watch a film with me, I’ve spent most of the time looking up from my Kindle, lurching between horror and disbelief at the amount of blood and gore – not to mention bad language – on the television screen.

I issue a second ten-minute warning, which falls on deaf ears. My hearts sinks as I realise certain warfare looms ahead.

My third warning is futile.

Finally, I’ve had enough. I turn off the television at the mains.

‘No, Auntie Alice, please… I’d nearly finished that level!’ Archie launches the joystick at the wall. It hits the framed photograph of Mum and knocks it off the coffee table. I rush over and snatch it up.

The day I took the picture, Mum was heading out of the door to get to the pre-booked cab that would take her to her regular ladies’ group meet-up. That week it was afternoon tea at the local garden centre.

She’d curled her hair and put a little eyeshadow and lipstick on. She seemed to be lit up from the inside.

‘You look lovely, Mum,’ I told her. ‘Bright and energised.’

‘You sound surprised.’ She laughed. ‘There’s still life in the old dog yet, you know.’

I knew she found great pleasure in the freedom of choice she had. Getting out to events, deciding what to have for tea, watching what she wanted on television. Things that most people wouldn’t give a second thought to, but that were massively important to her.

Even this long after Dad had gone, the novelty of living her life for just her remained fresh.

‘Smile for Candid Camera.’ I grinned as I picked up her camera from the side.

She rolled her eyes and stood still at the door for me. I could tell she was flattered, despite her objections.

That photo that Archie knocked to the floor as though it were nothing was taken just two weeks before she collapsed.

I use my sweater to dust it off and place it back on the table as I give Archie a look.

‘That’s enough.’ I try to affect a firm but calm tone, even though I’m shocked at his sudden angry outburst. ‘You’ve been playing now for two and a half hours. That’s far too long.’

‘I’m nine soon. I’m not a baby.’

‘You need to be at least fifteen to play some of these games,’ I try to reason with him.

‘Please put it on again, Auntie Alice,’ he whines.

‘I think you’ve had enough, Archie. How long does your mum allow you to play?’. . .

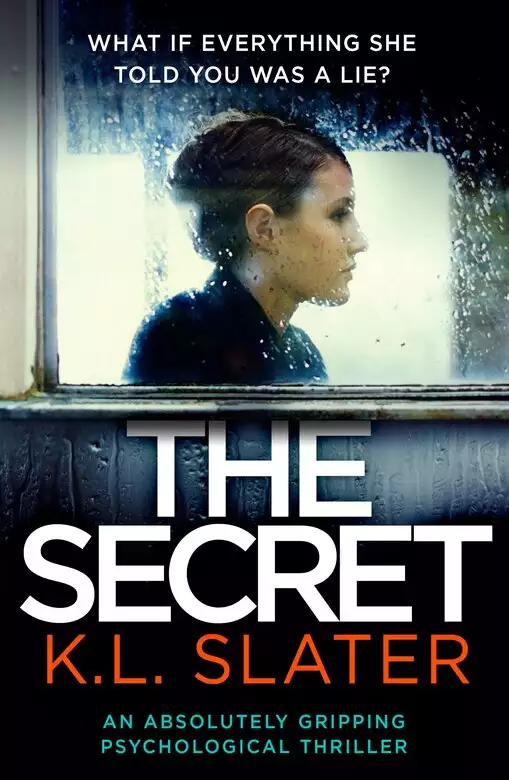

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved