The kite had dived-bombed around here; he knew it. Even though he couldn’t see it yet, he felt confident he would find it.

It was a perfectly blustery day, the exact reason he and Rose had decided to take the kite for its maiden flight. Slate and silver clouds marbled the powder-blue sky, misting the weak sunlight but taking none of its warmth.

But here in the undergrowth, Billy could see none of that. His bare arms felt cool, his forearms prickling as he stumbled over ancient exposed roots that felt like gnarled bones beneath his unsteady feet.

Still, Billy bravely ventured further into the dense woodland, beating a pathway through with his trusty stick.

He had a good sense of direction. His class teacher had said so last summer when they went on the mini-beast hunt, here at Newstead Abbey. And so Billy forged ahead, his inner compass telling him that the kite was definitely around here somewhere.

He wanted to show his big sister how grown-up he was, by recovering the kite and bringing it back to her. If he behaved himself, Rose might take him out again.

They hardly ever did stuff together these days, didn’t even play Monopoly or anything.

Billy heard a rustling sort of noise behind him. Ceasing the kite hunt for just a moment, he peered into the thick greenery but he could see nothing.

Perhaps it was a fox. Rose would be scared of that but Billy certainly wasn’t. He was eight years old now and Dad had said big boys like him weren’t scared of bears or wolves and certainly not foxes.

Billy inhaled the cool, damp scent of the earth, batting back the leaves and branches, eagle-eyed and waiting to spot the bright blue-and-white kite that Rose had bought him for his birthday just a few weeks ago.

A snapping branch and more rustling behind him. Billy spun around, brandishing his stick in case a fox was moving in to attack. His eyes caught a shadowy movement and then a figure stepped out of the foliage, towards him.

Billy breathed out and frowned. What was he doing here?

‘I’m looking for my kite,’ Billy said by way of explaining. ‘I don’t need any help.’

It would be just like him to take all the glory with Rose.

Billy looked up at him and thought how his face looked… different, sort of angry and he hadn’t answered him yet or explained why he was there. And yet Billy knew he hadn’t done anything wrong. His mouth felt dry and his chest burned.

‘I’ve got to get back to Rose now,’ he said, turning to run from the bushes, but before he could dodge past him, two strong arms shot out and held him fast.

Billy heard the chatter of voices close to them and he tried to call out but found he couldn’t because there was a powerful hand clamped over his nose and mouth.

He kicked and struggled but quite soon he couldn’t get his breath at all. He heard a crow cawing up ahead and he thought about his new kite, torn and lost in the undergrowth.

Billy strained to pull in breath to his straining lungs through fingers that were wrapped around his nose and mouth like an iron mask.

The voices he’d heard before sounded muffled and far away from him now.

Slowly, like a fading light switch turning, everything around him went very, very dark.

I sweep the book scanner across the two large-print Catherine Cookson novels Mrs Groves has spent the last thirty minutes selecting, and wait for the beep. Once I’ve checked they’ve successfully updated to the Library Management System, I push them back across the counter.

‘Would you like to sign our petition, Mrs Groves?’ I ask.

The old lady slides the books into her shopping bag and peers at the list of signatures I’m holding in front of her. ‘What’s it for, dear?’

‘We’re campaigning to save the library,’ I explain. ‘The local authority have issued a list of possible closures for next year and Newstead library is on there.’

‘Really?’ Mrs Groves frowns. ‘But that’s preposterous.’

‘I know but it could happen if we don’t actively do something about it,’ I explain. ‘It’s happening all over the country. Libraries are closing on a monthly basis.’

Mrs Groves looks at me. ‘You know it’s wonderful, the work you do here in the village, Rose. You make the library such a friendly place to come…’ Her face changes and I brace myself. ‘All in spite of everything else you’ve had to cope with… the tragedy you went through…’ Her eyes shine.

‘Thank you.’ I lower my eyes and smile the smile before moving on. ‘But this is about standing up for what we believe in, isn’t it? They’ve taken so much from our village as it is.’ I push the petition a little closer to her.

Mrs Groves adjusts her spectacles and takes the paper and pen.

‘Very true but I’ll tell you now, they’re not going to take our library, dear.’ Her spidery scrawl fills the next available box on the petition grid and she looks up defiantly. ‘We’ll make sure of that.’

I smile, silently wishing it were that simple. Newstead has one of the smallest libraries in the county of Nottinghamshire. We open for a total of just three days a week; all day on a Wednesday and a mixture of mornings and afternoons on the other weekdays.

I like working here and I’ve never had ambitions to move to one of the bigger libraries. I started my career about eight years ago, when I finished university, as Assistant Librarian to Mr Barrow. And when Mr Barrow eventually retired and I’d had the requisite interview, they made me Librarian.

The library is housed in a flat-roofed building tucked neatly away off the main road and sits opposite the primary school at the entrance to the main village. On a fine day, from the main desk, I can see the woods beyond the busy Hucknall Road that skirts past us.

The sun, on the days it shines, bathes my workspace from mid-morning to mid-afternoon.

Inside, the library decor is tired and the whole interior is now rather grubby in places. The wiry, grey carpets are worn worst where the heaviest footfall lands and the fabric on the edges of the chair cushions in our comfortable reading area is torn and frayed.

In winter the cold air seeps in through the rotting wooden window frames and the antiquated warm-air ducted heating system probably malfunctions on more days than it works.

But people like coming here all the same.

Miss Carter, a lifelong resident of the village now in her mid-eighties and living on Abbey Road with her thirteen cats, reliably informs me she can sense the library has ‘a subtle, sacred energy’. I suspect she might change her opinion if she heard Jim Greaves, the part-time caretaker, cursing loudly in his broad Geordie accent when the heating is on the blink again.

Still, I do know what she means. Even though it desperately needs upgrading, the place has a nice feeling about it. I put it down to all the wonderful books we have here. Shelf upon shelf of sparkling characters, addictive storylines and worlds that feel real enough to get lost in for a spare hour here and there, or for days on end.

I run a couple of fundraising events a year and from the proceeds, we’ve managed to buy some colourful bean bags to brighten up the children’s fiction corner a little, and we also had enough left to equip a mother and baby room, located next to the main toilet.

The flat roof sprung yet another leak last week, prompting Jim to buy another brightly coloured bucket from petty cash, and the whole place is desperate for redecorating, but I like working here.

I feel comfortable and safe, despite everything that’s happened.

My job allows me full contact with the villagers and even some of the new people who’ve moved here in recent years, without having to get fully involved in their lives. I’ve learned how to wear a convincing mask during my working hours. I say the right things, smile that smile and reassure everyone that despite the tragedy that happened here sixteen years ago, I’m OK and soldiering on.

I’ve realised that’s all they really want: to show me that they haven’t forgotten about Billy, and for me to say that yes, I’m fine now.

So that’s exactly what I give them and watch with a weary resignation as the relief floods over their concerned faces.

Nobody ever mentions Gareth Farnham.

The full horror of what he did here is still too much for the village psyche to handle. But the legacy of him hovers, like an undulating cloud of flying insects, above the heads of all of those who remember.

Over the years, I’ve learned the correct response to every question, each sympathetic look and every well-meaning touch of the arm. I can keep it up no problem until I get home and close the door behind me.

Then it’s a different story altogether.

Today is a half-day at work, so on the way home I plan on stopping off at the Co-op to pick up some bits for both myself and for Ronnie, my next-door neighbour.

As I sit re-jacketing a couple of our well-worn titles, I can’t help worrying a bit about him.

A fiercely independent man now in his late seventies, Ronnie has been out of sorts for the last few days with a nasty stomach bug and on top of that, his legs have started playing up; stiffening up and aching terribly if he walks too far. Yet I have to virtually beg for him to let me help him.

‘You’ve enough to do, Rose, without worrying about me,’ he’d complained when I’d popped round yesterday and checked on the sparse contents of his cupboards and fridge.

I’d rolled my eyes at him.

‘Ronnie, I’m just getting you some milk and bread on my way home from work tomorrow, OK?’

‘OK.’ He’d given me a little smile, suitably chastised.

Ronnie might be just a neighbour to some but, to me, he feels more like family. He’s always been there. I was born in this house and I remember Mum telling me that, virtually as soon as I could walk, off I’d toddle next door to the Turners’ house to get spoiled with sweets and Sheila’s legendary home-made strawberry ice cream.

‘Ronnie used to leave the little gate between our back gardens open so you could nip through and see Sheila whenever you liked,’ Mum remembered fondly one time. ‘And when Ronnie and your dad went for a pint, you used to try and follow them down to the Station Hotel.’

From the first moments Billy went missing, Ronnie and Sheila Turner were there for us. Ronnie stayed up all night to co-ordinate a community search of the abbey grounds and the local woods early the next day, and Sheila made drinks and sandwiches for everyone while we all waited for news. The legion of police, drafted in from all over Nottinghamshire, said they’d never seen anything quite like it.

When they found Billy’s body two days later, Ronnie and Sheila were there to catch us as we fell. We were feathers in a storm for days that bled into weeks then months and they held us down, stopping us from drifting into oblivion.

Sheila died just over five years ago and now, with Mum and Dad both gone too, there’s just me and Ronnie left. And I owe him.

Picking up a few bits for him from the store is never going to be a problem.

From my desk, I keep an eye on the clock and watch the unstoppable tick of the hands towards one o’clock.

Most people can’t wait to knock off work but it’s never like that for me. I always dread finishing time.

Once the last customer has left the library, Jim locks the external doors and stands rattling his keys. When I tell him I have some things I need to finish off, his face drops and he disappears into the back office again.

I feel bad because I know he can’t go home to Janice, his wheelchair-bound wife of forty years, until the building is empty.

But it’s just one of those days and I don’t feel strong enough to leave yet. I need to work up to going home.

I start by running an update to the LMS software while I tackle the big pile of today’s checked-in books, returning them to the shelves.

Paula, my assistant, only comes in on Wednesdays when we stay open all day. On half-days, I’m on my own. I don’t mind it, I like the variety and find that the simplest duties – like re-shelving the returns – bring back happy memories of when I first volunteered here and life was still safe and simple.

Books helped me get well back then and I feel happiest now when I’m around them. Sometimes I wish I could put up a camp bed in the back office, and then I’d never need to go home at all.

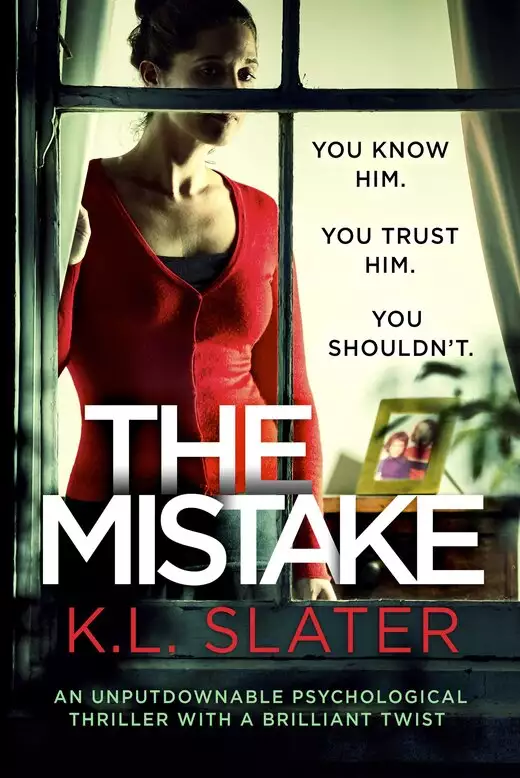

I load the returns on to a trolley and push it down to the bottom wall of shelves: the Crime section. It’s probably the most popular genre in the library.

Our customers love a good mystery, a page-turner. They seem fascinated by terrifying tales or awful deeds that could quite feasibly happen to them in their own ordinary lives. But of course that’s because they are safely afraid; they can close the book at any point and keep those emotions firmly in check.

When I was younger, I used to love reading crime novels for exactly this reason. My choice of late-night read before sleep beckoned was often a classic Agatha Christie or a chilling Ruth Rendell mystery.

But I haven’t touched a book like that in sixteen years.

Reading about deceitful personalities, the hidden underbelly of society and unreliable characters who appear to be one thing but are soon found out to be something else entirely… all that stuff now fills me with a curdling discomfort that can last for days.

After I’ve re-shelved the returns and checked that the update is complete, I enter the new books that were delivered mid-morning onto the system inventory.

We’ve a copy of the new Jeffery Deaver novel and two copies each of the latest blockbusters from Martina Cole and Val McDermid. They are all reserved and have been for weeks. In fact, one of the Martina Coles has Jim’s wife’s name on it. Hopefully, that will be a small consolation for her when he rolls home late from work yet again, courtesy of moi.

We have lots of keen readers in the village who still struggle to make ends meet, even all this time after the pit closed. They’ve never fully recovered, and never will. Especially the older residents. They were once valued contributors to the UK’s national coal supply and now, well, they’re just about managing on their reduced pensions.

They almost certainly haven’t got the funds to splash out on their favourite author’s latest hardback.

Next job is sending out the emails, texts and in some cases, for our less technical, older customers, I ring, leaving a message to tell readers their long-awaited books are now available for collection.

Tomorrow, in they’ll stride with purpose, their faces bright, their smiles of anticipation in place, and for a few hours, they’ll forget about their problems.

And when they return their books, we’ll have lengthy conversations about what they thought of the storyline, the setting, the characters. It’s one of the highlights of my job and it’s a massively important function of this library.

Jim’s face lights up when I hand him the book.

‘This will help my Jan with the pain far more than her medication ever could.’ He looks genuinely touched and pats the cover of the novel. ‘Cheer her up no end, this will. Thanks, pet.’

I smile and feel a sense of resolve inside. This is precisely why we can’t afford to let them close the place down.

The moment I leave the building, all positive thoughts desert me and I catch myself in exactly the same tortuous place; relentlessly checking again.

Every single day, for goodness knows how many years, I’ve promised myself I’ll try to stop doing it. But once I’m outside in the open air, even if there are plenty of people around, it’s an automatic reaction.

It honestly feels like there’s not a thing I can do about it.

Looking behind me every thirty seconds, monitoring the cars driving past to check the same one doesn’t keep passing me. I never listen to music while I walk; I couldn’t possibly. I need to be fully aware of any footsteps approaching behind. I cross the road if I pass by bushes or trees and I always give a wide berth to shadowy alleyways.

Years ago, Gaynor Jackson, my therapist, said, ‘This compulsive behaviour will exhaust you, Rose. You have to stop.’

But even after all this time, it’s still the only way I can feel remotely in control.

One of the reasons I stopped turning up for my therapy appointments was because I couldn’t stand listening to the constant utopian ideology that Gaynor spewed on an endless loop.

She’d repeat the same clichéd phrases: ‘You can learn to manage your fear’ and ‘you must strive to live in a state of relaxed awareness.’ She believed in the stuff she told me, really believed it could work and it might have done. If only it were as easy as it sounded.

Gaynor meant well, I’m sure. But her advice all came from a textbook. It was clear from her sunny disposition and naïve expression, when I tried to articulate my terror, that she had never been in fear of her own life.

She’d never lain awake in the summer months, sweating buckets in a stifling bedroom because she was too scared to open even a small window in case someone climbed up the drainpipe and forced his way in.

She’d never had to run to the bathroom to be physically sick when she heard a noise out in the garden at dusk and felt too afraid to peer out of the curtains.

It wasn’t Gaynor’s fault, of course. I realised a long time ago that unless a person has experienced true terror, there is nothing you can do to make them understand how utterly debilitating it can be.

Or how your safe, ordinary life can disappear in the space of a heartbeat.

At first, Rose hadn’t even realised that someone was watching her.

Weighed down with an enormous black art portfolio case, a shoulder bag and a large wallet that was full of art supplies, she juggled her load, swapped hands, but still almost tumbled from the passenger platform.

The bus stop was situated on Hucknall Road, which traced the edge of Newstead village leading to the A611 towards Nottingham. The village sat on one side of the road and Newstead woods on the other, a curious merging of the sharp steely edges of a moribund industry and the soft green haze of nature.

Rose sighed as her feet touched the pavement. After a good day at college, the same familiar air of resignation had settled over her during the journey.

It happened every day. As the bus trundled closer to home, the heavier her heart felt, hanging there in her chest.

It hadn’t always been that way. The atmosphere at home had grown steadily worse over the last few months. Mum and Dad screaming at each other, both saying awful things designed to inflict the maximum hurt.

But Rose had noticed a new, unwelcome development. When they tired of insulting each other, they seemed to have taken a liking to turning on her. Voicing everything that was wrong with her, everything she’d done wrong, every way she continuously disappointed them.

Every day, Rose asked herself how much longer she could stand it.

She would turn eighteen years old in June and that was just a couple of months away now. If she really wanted to, she could leave the village and make a new start somewhere a long way from here. Nobody could stop her.

It felt good and powerful to imagine it without considering how she’d begin to support herself. And Rose knew she could never leave Billy. So it wasn’t a real option but still… it sometimes helped when she tried to block out the worsening situation at home.

Looking at the telltale small puddles here and there in the uneven pavement, Rose could see it had rained here quite heavily earlier in the day. She hadn’t noticed the weather at college, snug in a classroom, absorbed in her art.

But it had begun to rain again and, as Rose stood there, still trying to shuffle her various loads into a manageable position, she could smell the dank, old earth and fresh, young leaves; not for the first time, she thought how strange it was having a wood so close to the road.

She’d barely found her balance in her flat, sensible shoes, when the pneumatic doors whooshed closed behind her and the bus rumbled off down the road. She lost her grip and the bulky wallet slipped from her hands, spilling out her precious soft pastels on to the asphalt.

‘Looks like you might need a bit of help,’ a voice said behind her. ‘Can I carry something?’

She turned to see a man with an amused expression standing watching her. The first thing she noticed was that he looked quite a bit older than her, she guessed probably in his late twenties. He stepped clear of the trees and she noticed his waxed green jacket shone with droplets of water and his hair was damp, stuck to his forehead and cheeks.

She looked up to the sky but it was still only spitting, certainly not enough to fully douse someone.

‘I know, I’m wet through.’ He grinned, displaying slightly crooked teeth in an attractive smile. ‘I’ve been climbing up in the trees and brushing against the leaves. For the photos, you see.’ He held up an expensive-looking camera.

Rose thought how quiet it was, now that the bus had gone. There was no one else around. The rainclouds had gathered moodily above them and she wondered how long it might be before the heavens truly opened.

She lay down the portfolio case and began to gather up the scattered pastels, praying none had reached a puddle. There was no way her parents would be able to afford more and it would be another thing for them to chastise her about.

He was staring at her. She felt her cheeks begin to heat up, despite the chilly air.

‘So, what do you say?’

‘I’m sorry?’ She packed the last crayon back in the wallet, stood up and swapped the ungainly portfolio case over to her right hand.

‘Can I help you carry anything?’

‘Oh, yes.’ Her cheeks heating up, she held out the large portfolio case. ‘Thanks.’

Although she couldn’t deny part of her was intrigued, Rose wished the stranger would just go on his way and leave her alone. She was only too aware she looked like an idiot. Bright red cheeks to match her pale-red hair. What a mess.

‘Gareth Farnham,’ he said. ‘I’d shake your hand but you. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved