- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

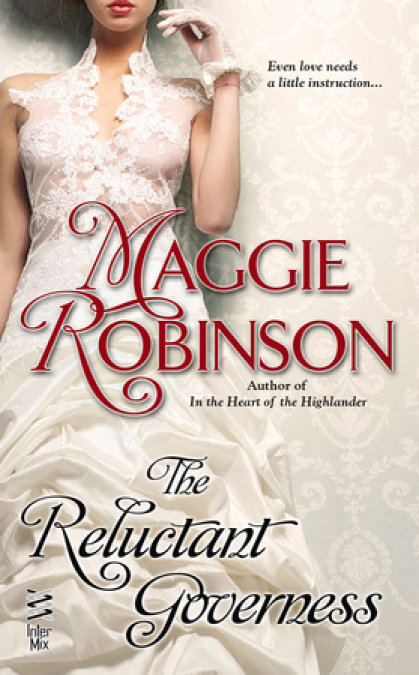

From the author of In The Arms of the Heiress, a seductive romance about getting schooled in the ways of the heart—and desire…

A secretary for the renowned Evensong Agency, Eliza Lawrence may have a pretty face, but she’s much prouder of her mind and her morals. When she’s pressed into temporary governess duty as a favor to her boss, she doesn’t expect to bend one bit for the rakish Nicholas Raeburn. Not even when he opens the door to her half-dressed…

Despite his bad reputation, Nicholas is a man of honor. To Nick’s way of thinking, he doesn’t need any help raising his daughter, Domenica. If only he weren’t so drawn to the meddlesome woman’s sparkling wit and uncommon beauty...

But when an act of misplaced chivalry goes seriously awry, resulting in mayhem and almost murder, Eliza becomes the only woman he can depend upon. Nick will do anything to protect his family, but who will protect him from falling in love with his reluctant governess?

Praise for the Ladies Unlaced Novels

“Downton Abbey fans will fall in love…A must read!”—Tessa Dare, USA Today bestselling author

“A fun, light and very sexy historical.”—Smexy Books

“Charming…Filled with action, love and secrets.”—Fresh Fiction

Maggie Robinson, author of the Ladies Unlaced series, including In the Arms of an Heiress and In the Heart of the Highlander, is a former teacher, library clerk, and mother of four who woke up in the middle of the night absolutely compelled to create the perfect man and use as many adverbs as possible doing so. A transplanted New Yorker, she lives with her not-quite-perfect husband in Maine, where the cold winters are ideal for staying inside and writing hot historical romances.

Release date: August 19, 2014

Publisher: InterMix

Print pages: 311

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Reluctant Governess

Maggie Robinson

Mount Street, London, October 1904

“I would not ask if it were not so urgent. With me going away on a delayed honeymoon, you know I can’t afford to spare you here at the office. But Nicholas needs someone reliable today. Yesterday, really.” Lady Mary Raeburn widened her hazel eyes, hoping she resembled an entreating puppy. She prayed Eliza Lawrence would be softhearted enough to return to her previous employment as a governess for a few days, rather than the efficient Evensong Agency receptionist she had proved to be the past two months. Mary had great hopes for Eliza, which did not include sticking her with her new brother-in-law’s illegitimate child forever.

Illegitimate. What a cruel concept. Mary was sure Domenica had every right to exist as much as any other little girl.

She’d caught a brief glimpse of her yesterday, all black ringlets and enormous dark eyes. The child was beautiful, even if she did not favor her father, Nicholas Raeburn, wicked artist and Continental reprobate in the least. But Domenica’s mother had been Italian, so that explained it.

“Oh, Mary, I don’t know,” Eliza said. “Is there no one else?” She waved in the general direction of a massive oak filing cabinet that was indeed filled with numerous governess candidates.

“It won’t be for very long, I promise. Just a matter of days. Oliver will have to warn—I mean vet—the applicants properly. We can’t put just anyone in Mr. Raeburn’s household—he’s rather unconventional, you know. An artist with somewhat peculiar ideas. It would be awful for the child to become attached to someone and then have the woman leave in high dudgeon.”

Mary was counting on Eliza’s good sense to ignore whatever mischief her brother-in-law got up to now that he was back in London. She’d heard the stories. A permanent employee would have to be very flexible when it came to dealing with him. A contortionist. Not only did Mary see Domenica yesterday, but there had been three totally nude young models traipsing up the stairs to the studio in Nick’s Kensington house. Surely Nick had the money to supply them with robes.

He didn’t seem to even notice them, but his brother Alec had. Mary had berated her husband all the way to Raeburn House, rather wishing for her old black umbrella.

Alec had kissed her and called her silly, then ably demonstrated he had no interest in any other woman but her. The interlude, pleasant though it had been, had distracted her from packing for their transatlantic trip to New York tomorrow. She must finish, once she got Nick’s difficulties settled.

Lady Mary Raeburn was famous for settling difficulties. One had to live up to the Evensong Agency’s motto: “Performing the Impossible Before Breakfast Since 1888.” She had worked for her Aunt Mim’s agency the past four years, supplying everything from housemaids to husbands to the peerage for a price. An exorbitant price, according to her husband.

But look how well she’d solved his problems. He was happy for the first time in ages, and becoming quite adept at the devoted husband business.

Mary had only met Nicholas Raeburn yesterday, but she could not see the man as anyone’s devoted husband. And that was her one misgiving. Eliza was very pretty in a chocolate box sort of way, blond and blue-eyed. All wrong for a governess, really, just asking for trouble. If Nick noticed her, there would be hell to pay, and Mary would be delivering the payment personally. With her umbrella if need be.

Of course, Nick hadn’t asked Mary to find him a governess. He seemed to think Domenica was perfectly happy with his little kitchen maid and the models that darted in and out of his house. The child had been half-dressed and barefoot, thumb in her mouth, and had fled when Mary smiled at her. Certainly she needed a governess, and Mary had told him so.

“You were so good with the Hurst children,” Mary continued. “And Domenica is nothing like little Jonathan. She’s very, very quiet. As I said, it will only be for a few days—a week at the most. I’ll get Oliver started immediately to find your replacement.”

“The quiet ones are the most dangerous,” Eliza grumbled. “I’ve gone through all this before, you know. When Mr. Hurst took me out of the typing pool, he promised me it would be temporary. I was his children’s governess for a year, Mary. If I hadn’t met you by chance at the Forsyth Palace Hotel, I’d still be there in the schoolroom. You know how grateful I am to you for rescuing me. I love this job—it’s so very interesting to meet the clients and do my little part to help.”

“And you have been a great credit to the agency. I know Oliver and Aunt Mim depend on you.” Oliver Palmer had once held Eliza’s position, and the two of them exchanged advice and strategies. Since they were still short-staffed, Eliza’s duties had expanded beyond the reception desk to office manager. Recovering from a problematic surgery, Mary’s assistant Harriet only worked part-time. Mary herself had spent most of the summer and fall in Scotland learning how to be a baroness. She was not entirely sure the lessons had stuck.

“It won’t be long,” Mary repeated, sensing Eliza weakening. “I promise.”

“Oh, very well. How bad can it be?”

***

Eliza soon found out. She went home to her mother’s, packed a small suitcase, took an omnibus to Kensington High Street, and followed Lady Raeburn’s directions to Lindsey Street. Halfway down the short block, she climbed the steps of Nicholas Raeburn’s neat terraced house. Eliza was not going to use the servants’ entrance—she was no one’s servant. She’d had a secretarial course, and her late father had been a respected accountant. She’d worked in a barrister’s office before Mr. Hurst drafted her to be his motherless children’s governess, and she had managed both jobs with aplomb.

Eliza was a managing sort of girl. People expected her to be uselessly ornamental because of her looks, and she liked to surprise them. She was not bookish by any means, but she was practical. Levelheaded. Quite good with numbers, too, a legacy of her father’s. One day she’d like to own her own business, although she was uncertain what kind of business it might be, or where the money would come from to found it. Eliza admired Lady Raeburn for breaking the mold of the delicate Edwardian female. Even now that she had married a Scottish baron, she still came down to London to work a week or so every month. She was frequently on the telephone to her aunt, and marconigrams and letters flew back and forth when she wasn’t.

Eliza rang the brass bell next to the sage green door. The bell needed polishing, but that would not be within the purview of a governess. The street was absolutely silent, the white façades of the identical buildings rather blinding in the bright October sun. The houses were newish, not more than two decades old, and respectable, and Eliza wondered why the “unconventional” artist Nicholas Raeburn had purchased property here. Surely he would have been better off to remain abroad, perhaps in Paris where morals were more disposable.

Or so she thought. Eliza had never been to Paris, or anywhere, really. She knew nothing about art or artists. She’d accompanied her frail mother to the National Gallery on a few occasions, and had been unmoved by the vast canvasses celebrating war and gore through the centuries, interspersed with fat cherubs hovering above star-crossed lovers. Heathen that she was, Eliza thought the frames more useful.

A lace curtain twitched on the second story. The window above was bare. The studio, probably. Lady Raeburn had described the layout of the house; there were two large rooms on each floor. Eliza would be sharing a bedroom with the little girl. Domenica. It meant Sunday in Italian, quite a lovely if unusual name.

She waited, listening for footfalls on the stairs. There weren’t any. Putting her bag down, she rang the bell again.

And waited some more. Perhaps she should go down the basement steps and go in by way of the kitchen. Someone had to be down there, surely. It was almost teatime, and Eliza had not had lunch in her haste to pack and save the day. She wouldn’t turn down a biscuit, would be happy to share one with her new charge.

Third time was the charm, they said. Eliza gave the bell a vigorous—well, vicious—turn. If no one answered the door, she would go back to the Evensong Agency and await instructions.

Her resolve proved unnecessary. The door opened, and so did Eliza’s mouth.

The man before her was no butler. For one thing, he appeared to be wearing paint-stained silk pajama bottoms, something no self-respecting butler would wear, even to sleep in.

And nothing else.

His hair was auburn, curly, and disheveled. He had not shaved lately, although she wouldn’t call what he sported a full-fledged beard. She gripped the railing as she noted a golden ring pierced through one ear, and the tongue of a serpent licking its own tail around his left bicep. She shut her eyes. The ring and the snake was still there when she opened them.

“Oh good. You’ll do, I suppose. Tubby’s told me all about you. Come in, come in.”

Eliza remained rooted to the front step. Who was Tubby? She could not picture Mary Evensong Raeburn ever answering to such a name even if she did carry a bit of extra weight now that she’d married. Happiness seemed to include an extra éclair or two.

“Cat got your tongue?” He thrust out a dirty hand. “I’m Nick Raeburn. Tubby didn’t tell me yours, just that you were a prime article.”

Should she be flattered? Eliza didn’t think so. “E-E-Eliza. Lawrence. Eliza Lawrence.”

He gave her a cheeky grin. “Well, E-E-Eliza-Lawrence-Eliza Lawrence, welcome to my humble atelier. We won’t have much light left, so you’ll have to take off your clothes at once. Normally I like to go through some polite preliminaries, but we don’t have time. The other girls are waiting.”

Eliza gripped the handrail more firmly. “I beg your pardon?”

“Tubby said you were quite the la-di-da lady. I see he was right. Come now, don’t be shy. Perhaps you’d like some whiskey to relax you. My family happens to make the best single malt in the Highlands, and that’s saying a lot. I’ve got cases of it. Come on up and we’ll have some and then you can get naked.”

Eliza recoiled at the hand that was proffered. “Mr. Raeburn, I believe you are under a misapprehension.”

A bronze eyebrow rose. “I’m under a lot of things, love. Aren’t you Tubby’s friend?”

“It depends on who this Tubby is. I have been sent by your sister-in-law Lady Mary Raeburn to act as an emergency governess for your daughter. I am certainly not going to disrobe now or at any time in the future, no matter how much whiskey you ply me with.”

It was his turn to be shocked, but it didn’t result in him making a mad dash for some proper clothing. “An emergency governess? What rot. I told Alec’s interfering little wife we’re fine as we are.”

“Oh, I can see that.” Eliza wished she could unsee. She had never in her life had such an encounter with a member of the male sex. He was practically naked himself. In broad daylight on the front steps, where anyone might see him. When she had lived in Mr. Hurst’s house, she’d never seen her employer with a hair out of place or without a cravat the whole year she was there.

Nicholas Raeburn’s jaw twitched. “You doubt we’re fine?”

“It’s not for me to doubt. I came here as a favor to Lady Raeburn. I confess it’s a great relief you do not require my services.”

“You aren’t a model, then—this isn’t some lark Tubby put you up to.”

“I do not get put up to larks, Mr. Raeburn,” Eliza said quite firmly.

“Pity. I do need a girl, and as I said, you would have done. Just. Blondes in general bore me, but you have a certain spark.”

“Thank you so much.” Her insincerity was deliberate. What a rude, reprehensible man.

Just then Eliza’s attention turned from the gleaming gold earring to the long hallway behind its wearer. A little girl of about four or five was standing on a chair and attempting to climb into an enormous Chinese urn. Any warning cry Eliza might have made came too late. The child disappeared into the pottery, and then proceeded to shriek.

“What the devil?” Nick Raeburn raced down the hall, carpets flying. “Not again, Sunny! I’ve told you a dozen times!”

Eliza couldn’t help but follow him. She peered down into the vase. A pair of deep brown eyes blinked back at her. The child giggled, then put her grubby hands over her face.

“We can still see you, moppet, even if you can’t see us. If you break this valuable antique, I’ll have to send you to the orphanage.”

“Don’t say such things, even in jest,” Eliza hissed. “Children are very literal minded.”

“Sunny knows I don’t mean it. I’d never send you away, would I, sweetheart?” He smiled down at his daughter. Eliza noted it was a rather nice smile, nothing like the semi-leer he’d given her on the doorstep.

“No, Papa.” Domenica—Sunny—sounded as if she were at the bottom of a well. She was a very little girl, and the vase was very big.

“She’s done this before?”

“Several times. Sunny likes to play hide-and-seek. I’m forever finding her in one cupboard or another.”

“It’s not safe. Who is minding her?”

Nicholas Raeburn ran a paint-stained hand through his disordered hair. “Sue. The kitchen maid. But I suppose Mrs. Quinn needs her help getting supper ready. I’m having a sort of welcome home party tonight.”

“And where will Domenica be while you have this party?” Eliza asked.

“In bed, of course.”

“Who will put her to bed? I imagine this Sue will be serving your guests.”

“I don’t know. It will all work out,” Nicholas said, sounding annoyed.

“Will it? Why does your child have no proper nurse or governess? You can afford one. For that matter, where is your butler?”

“You are just as bad as my sister-in-law. Though she is a vast improvement on Alec’s first wife. It’s really none of your business.”

“Lady Raeburn has made it my business. She’s concerned for the child’s welfare, and frankly, so am I.”

“Will you help me out now, Papa?” came a little voice.

Good grief. They’d stood over the girl, arguing, when she might be smothering in the confines of the urn. Eliza watched as Nicholas tipped the thing on the Turkey carpet, and Domenica crawled out, a little dustier than before she went in. She gave a very creditable curtsey to Eliza. “Are you to be my new nanny? My old one is in Heaven with Mama.”

“I don’t know.” Eliza looked up at Nicholas. “Am I?”

He threw up his hands. “Oh, fine. But it’s just temporary. I will find someone that suits me.”

“Temporary is exactly the word. The Evensong Agency is reviewing applicants even as we speak for a responsible person to join your household.”

“Damn it! I never asked Mary to do anything. She may lead my brother around by his co—nose, but I’ll be damned before she runs my life. I only got back to London last week. We’re not even unpacked.”

Eliza glanced around the hallway. She had never seen such a number of antiquities, paintings, patterns, and embellishment in a private house in her life. One hardly knew where to look first. Could there be even more stowed away in boxes? It boggled the mind.

“I bought the house furnished,” Nicholas said, anticipating her question. “An artist friend of mine had to let it go. These are his things. Well, mine, now, I suppose.”

“It’s very—decorated,” Eliza said, searching for the right word. She longed for a broom and a dustbin. There was just too much stuff.

“Yes, isn’t it fabulous? Leighton would eat his heart out if he were still alive. I’ll get your bag.”

Eliza felt a little light-headed watching the man walk to the open door. His pajamas were slipping down his slim hips, and she thought she could see—

There was a tug on her coat. “Come up to my room. We can have a party of our own.” Domenica smiled, and Eliza followed the child up the stairs, wondering what precisely she’d gotten into and just how long “temporary” was.

Chapter 2

He was in a pickle now. Damn Maria for dying and leaving him in the lurch and at the mercy of Miss Eliza Lawrence. Of course, Maria must have been close to eighty. She had been Barbara’s nurse, and even then she had been too old. But to die on a train across France was just plain careless, especially since Sunny had been in the berth beside her.

Nick shuddered to think what would happen if his daughter realized that Maria was not just sleeping. In the week since, she seemed to be satisfied that her nurse had gone to Heaven to visit her mother without realizing she’d been next to a corpse for who knows how long. In a few months, perhaps her memories of Maria would be as hazy as they were of Barbara.

Nick had not expected fatherhood to fall upon his shoulders. In fact, he was completely unaware of Sunny’s birth until two years ago, when Barbara summoned him to her villa. She had done very well for herself, but now she was dying. She had a child, possibly Nick’s. Could he keep her?

Possibly. Perhaps. Maybe. To give Barbara credit, she did not lie to him, couching his paternity in the vaguest way. There had been other men—and Nick remembered them—but no one good enough to raise her daughter. He had been both flattered and frightened. But he was a Raeburn. Raeburns did the right thing, or died trying. So he had taken Sunny away with Maria, and let Barbara abandon her bravery to die.

There was money. Quite a lot of it. Barbara had been shrewd with both her body and her finances. Sunny would never want for anything, and neither would Nick, should he choose to touch any of the funds.

He did not choose. He had an inheritance from an aunt, and his paintings actually sold for outrageous sums. Along with a share in the distillery, his brother Alec had been beyond fair divvying up the family fortune. Nick wasn’t a starving artist any longer. Sunny would be an heiress, which should more than make up for her questionable provenance.

When he looked into her little face, all he saw was Barbara. After two years, it didn’t matter who Sunny’s father was—she was his. Nick had enjoyed the past few days alone with her. But now starchy Miss Lawrence would put a stop to freedom for both of them.

He’d intended on getting a proper governess eventually. It seemed eventually had begun this afternoon.

Nick loped up the stairs to the top of the house. What had been intended as servants’ quarters served ably as his studio. His friend Daniel Preble had knocked a hole in the roof and installed a very pretty domed window. The box room next door served as a photography lab, for Nick’s artistic visions knew no bounds. He split his day between painting and taking pictures as the spirit moved him.

Two nude Titian-haired girls were draped on a chaise, eating the apples that were to be props in his reconstructed photographic homage to Raphael’s Three Graces.

“Is she here, then?” one of them asked.

“No. False alarm. I think we’d better call it a day.” Nick raised a hand to stop their objections. “Don’t worry, I’ll still pay you for the full afternoon, and give you prints of what we already shot for your portfolios. Come round next Wednesday afternoon. I should have a third by then when Tubby’s girl comes through.”

“Too bad about Maisie’s man beating her. No amount of makeup would cover those bruises,” the other model said.

“Yes, it is,” Nick said darkly. He would see to Maisie’s man after his little dinner party. The fellow would not be using his fists on another woman after Nick had his say.

Daniel Preble had very kindly supplied him with a list of his favorite models, so it had been a seamless transition to get right to work as soon as Nick landed in London. He had only had the benefit of Maisie’s services for one day, but she was a good-natured little thing and he felt responsible for her welfare. Foolish, perhaps, when her own lover was ill-treating her.

The girls dressed as Nick organized his equipment. He was particular—he didn’t care if he smelled of chemicals or had paint in his ear, but his things were sacred. The housekeeper-cook and underage maid he’d inherited from Daniel were forbidden to come upstairs unless it was to tell him the house was on fire. He had no butler—there wasn’t room for one, now that he’d taken over the attics. The staff slept in the basement. He presumed Miss Lawrence would bunk in with Sunny as the little maid Sue had done.

His bedroom room was right next door. It was a bit unsettling to think of a strange young woman so close at hand, and yet so forbidden. Nick was used to acting upon his urges, but wasn’t it lucky he had no urge whatsoever for her? How awkward it would be to importune the governess. He was no Rochester, and Eliza Lawrence was no plain Jane Eyre.

The girl was very pretty. Not his type, of course, but as an artist he had an eye for beauty, and Miss Lawrence’s quintessentially English looks would attract attention anywhere. But there was nothing of the flirt in her. Her clothes were dull and her hat merely serviceable. She had no sense of style. Nick was a bit of a peacock himself, teased by his brothers for years at his love for color and texture. He was not going to pose as a black-and-white penguin anytime soon—Beau Brummell had a lot to answer for in dulling the social scene for decades. What was wrong with scarlet waistcoats and checked trousers?

The bathroom was on the landing below, and he locked himself in to rid himself of his dirt. It was the only room in the house he’d put his own imprint on so far. The walls were covered with his photographs. Wouldn’t he like to be a fly on the wall when Miss Lawrence saw them?

There was nothing shameful about the human body. He kept his in fine fettle. Thank the gods the old queen was gone and her priggish mores with her. Covered piano legs indeed!

Nick hadn’t bothered shaving in a couple of days—there had been too much to do getting settled in the new house. Daniel’s loss was his gain. Nick felt sorry for the fellow, having to leave such a splendid collection of objets behind. But Preble had fled to France, creditors hot on his heels, and Nick had been happy to help an old friend when they’d met up in Paris. He had offered Daniel the use of his villa in a tiny Tuscan town at a reasonable rent in exchange for the deed to the Lindsey Street house at a reasonable price. Daniel had been desperate to leave all this behind.

Nick had been gone so long on the Continent he wondered if his old cronies would recognize him. Even before Alec’s horrible first wife threw him out of the family home five years ago, he had spent most of his time traveling—hence the possibility of Sunny. The light in Italy was a vast improvement over a gray Scottish winter, and Barbara a warm bed partner. The other signoras and signorinas and madames and mademoiselles after Barbara were equally delightful. He sometimes wondered why he had agreed to return, but his brothers Alec and Evan had bedeviled him with an avalanche of letters, so here he was. And he reckoned it was time for Sunny to meet her uncles, annoying as they were.

He unpacked his kit and pulled out a razor. No butler. No valet. He supposed he might arrange a standing appointment at Trumper for a proper shave, but that would mean setting up some sort of schedule. Nick didn’t believe in schedules—why should one hem oneself in? He might not want to wake up early on a Tuesday, for who knew how he’d spend Monday evening?

Though things were bound to be much duller in London. Some of his wildest mates had settled down into suburban domesticity, hampered by wives and children and dogs and mortgages. Nick might be raising Sunny, but that was no reason to take vows of abstinence and self-abnegation. Barbara had trusted him, and she of all people knew what he was capable of.

The rasp of the razor required his concentration, and the next minutes were spent in the diligent removal of the copper bristles on his face. Beards were very much in fashion, which was as good a reason as any to eschew them. Nick didn’t wish to be caught with crumbs or drops of alizarin crimson adhering to his moustache, and his lady friends seemed to prefer a smooth cheek against their thighs.

Nick needed a local lady friend now that he was back. In his experience, most of the models he had used in the past were generally willing, but that sometimes complicated things. Jealousy amongst the girls was dead boring, and sometimes dangerous. Nick sported a sliced left eyebrow from a palette knife gone awry. He was lucky he hadn’t been blinded.

Satisfied that he looked a little less piratical, he ran his bath and sunk into the tub, closing his eyes to the photographs else he might become inspired and be late to his own dinner party. There would be time tonight to find someone, after he dealt with Maisie’s man.

The tension had just about disappeared from between his shoulder blades when there was a peremptory knock on the door.

“Papa, may I come in?”

“No, you may not, monkey. I’m taking a bath.”

“But Sue is sick in the downstairs bathroom, and I have no shoes on.”

Nick took that to mean his daughter did not want to use the privy in the corner of the back garden. He couldn’t blame her—the garden was a tangle. Daniel may have perfected the house, but had no interest in horticulture. The space would be ideal for photography once he hacked his way through the jungle, though.

“I’m sorry, love. A man needs his privacy. Get Miss Whatshername to take you outside.”

“But it’s cold!”

“I said no, Sunny,” Nick replied. “You may not enter. And what are the three reasons?”

“Because you said so, you said so, and you said so.”

“That is correct. Now off you go.”

He thought he might have heard the stamp of a bare foot, then Miss Whatshername’s mild admonition. Nick frowned—if Sue was sick, wasn’t it providential that the governess turned up? He hoped whatever she had wasn’t contagious, or Sunny would be next. She and Sue had been thick as thieves since last week, racing all around the house after Sunny’s confinement on trains and boats.

Mrs. Quinn could probably manage the dinner on her own. Nick’s friends weren’t fussy. As long as there was plenty of wine, the evening would be a success.

After a vigorous scrubbing, he rose from the tub and wrapped himself in a bath sheet. The bath was on a landing between the bedroom floor and the attics above it, and wasn’t it just his luck to run into Miss Lawrence in the hallway. He realized she’d seen him mostly unclothed in their two encounters today. It didn’t bother him, but from the look on her face, she was fairly horrified. Nick knew his tattoo bothered some, but he found the ouroboros’s symbolism of eternity comforting, despite the hell he’d gone through to get it. Even Plato had claimed the snake was the first living thing in the universe. Rebirth, renewal, the soul of the world—what could be better?

“We need to stop meeting like this,” he quipped, clutching the towel just in case it had a mind to horrify Miss Lawrence further.

“Do you not own a dressing gown? You have a young daughter who should not be exposed to such—to such—words fail.”

“There’s nothing shameful about the human body, Miss Lawrence. If you’re going to live here, you’d better get used to seeing it.”

Miss Lawrence’s rosebud mouth shrivel

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...