- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

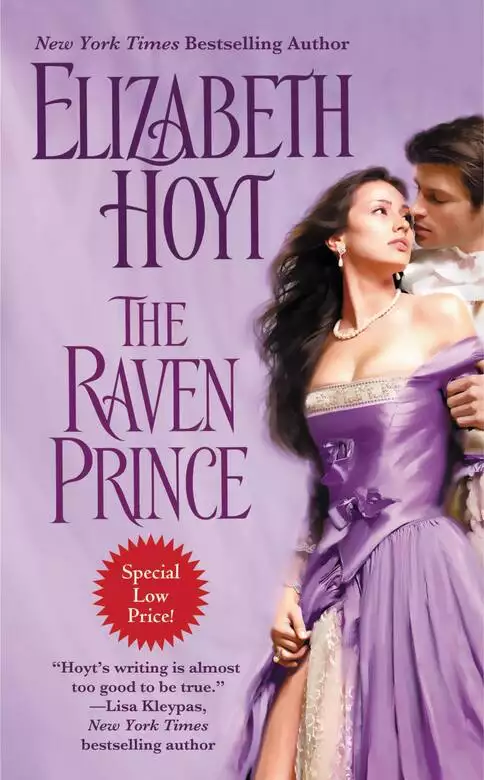

The Raven Prince: Booktrack Edition adds an immersive musical soundtrack to your audiobook listening experience! *

Widowed Anna Wren is having a wretched day. After an arrogant man on horseback nearly crushes her, she arrives home to learn that she is in dire financial straits.

THERE COMES A TIME IN A LADY'S LIFE

The Earl of Swartingham is in a quandary. Having frightened off two secretaries, Edward de Raaf needs someone who can withstand his bad temper and boorish behavior.

WHEN SHE MUST DO THE UNTHINKABLE . . .

When Anna becomes the earl's secretary, it would seem that both their problems are solved. But when she discovers he plans to visit the most notorious brothel in London, she sees red-and decides to assuage her desires . . .

*Booktrack is an immersive format that pairs traditional audiobook narration to complementary music. The tempo and rhythm of the score are in perfect harmony with the action and characters throughout the audiobook. Gently playing in the background, the music never overpowers or distracts from the narration, so listeners can enjoy every minute. When you purchase this Booktrack edition, you receive the exact narration as the traditional audiobook available, with the addition of music throughout.

Release date: November 1, 2006

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 392

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Raven Prince

Elizabeth Hoyt

—from The Raven Prince

LITTLE BATTLEFORD, ENGLAND

MARCH, 1760

The combination of a horse galloping far too fast, a muddy lane with a curve, and a lady pedestrian is never a good one. Even in the best of circumstances, the odds of a positive outcome are depressingly low. But add a dog—a very big dog—and, Anna Wren reflected, disaster becomes inescapable.

The horse in question made a sudden sideways jump at the sight of Anna in its path. The mastiff, jogging beside the horse, responded by running under its nose, which, in turn, made the horse rear. Saucer-sized hooves flailed the air. And inevitably, the enormous rider on the horse’s back came unseated. The man went down at her feet like a hawk shot from the sky, if less gracefully. His long limbs sprawled as he fell, he lost his crop and tricorn, and he landed with a spectacular splash in a mud puddle. A wall of filthy water sprang up to drench her.

Everyone, including the dog, paused.

Idiot, Anna thought, but that was not what she said. Respectable widows of a certain age—one and thirty in two months—do not hurl epithets, however apt, at gentlemen. No, indeed.

“I do hope you are not damaged by your fall,” she said instead. “May I assist you to rise?” She smiled through gritted teeth at the sodden man.

He did not return her pleasantry. “What the hell were you doing in the middle of the road, you silly woman?”

The man heaved himself out of the mud puddle to loom over her in that irritating way gentlemen had of trying to look important when they’d just been foolish. The dirty water beading on his pale, pockmarked face made him an awful sight. Black eyelashes clumped together lushly around obsidian eyes, but that hardly offset the large nose and chin and the thin, bloodless lips.

“I am so sorry.” Anna’s smile did not falter. “I was walking home. Naturally, had I known you would be needing the entire width of the throughway—”

But apparently his question had been rhetorical. The man stomped away, dismissing her and her explanation. He ignored his hat and crop to stalk the horse, cursing it in a low, oddly soothing monotone.

The dog sat down to watch the show.

The horse, a bony bay, had peculiar light patches on its coat that gave it an unfortunate piebald appearance. It rolled its eyes at the man and sidled a few steps away.

“That’s right. Dance around like a virgin at the first squeeze of a tit, you revolting lump of maggot-eaten hide,” the man crooned to the animal. “When I get hold of you, you misbegotten result of a diseased camel humping a sway-backed ass, I’ll wring your cretinous neck, I will.”

The horse swiveled its mismatched ears to better hear the caressing baritone voice and took an uncertain step forward. Anna sympathized with the animal. The ugly man’s voice was like a feather run along the sole of her foot: irritating and tantalizing at the same time. She wondered if he sounded like that when he made love to a woman. One would hope he changed the words.

The man got close enough to the bemused horse to catch its bridle. He stood for a minute, murmuring obscenities; then he mounted the animal in one lithe movement. His muscular thighs, indecently revealed in wet buckskins, tightened about the horse’s barrel as he turned its nose.

He inclined his bare head at Anna. “Madam, good day.” And without a backward glance, he cantered off down the lane, the dog racing beside him. In a moment, he was out of sight. In another, the sound of hoofbeats had died.

Anna looked down.

Her basket lay in the puddle, its contents—her morning shopping—spilled in the road. She must’ve dropped it when she dodged the oncoming horse. Now, a half-dozen eggs oozed yellow yolks into the muddy water, and a single herring eyed her balefully as if blaming her for its undignified landing. She picked up the fish and brushed it off. It, at least, could be saved. Her gray dress, however, drooped pitifully, although the actual color wasn’t much different from the mud that caked it. She plucked at the skirts to separate them from her legs before sighing and dropping them. She scanned the road in both directions. The bare branches of the trees overhead rattled in the wind. The little lane stood deserted.

Anna took a breath and said the forbidden word out loud in front of God and her eternal soul: “Bastard!” She held her breath, waiting for a thunderbolt or, more likely, a twinge of guilt to hit her. Neither happened, which ought to have made her uneasy. After all, ladies do not curse gentlemen, no matter what the provocation.

And she was, above all things, a respectable lady, wasn’t she?

By the time she limped up the front walk to her cottage, Anna’s skirts were dried into a stiff mess. In summer, the exuberant flowers that filled the tiny front garden made it cheerful, but at this time of year, the garden was mostly mud. Before she could reach it, the door opened. A small woman with dove-gray ringlets bobbing at her temples peered around the jamb.

“Oh, there you are.” The woman waved a gravy-smeared wooden spoon, inadvertently flinging drops on her cheek. “Fanny and I have been making mutton stew, and I do think her sauce is improved. Why, you can hardly see the lumps.” She leaned forward to whisper, “But we are still working on dumpling making. I’m afraid they have a rather unusual texture.”

Anna smiled wearily at her mother-in-law. “I’m sure the stew will be wonderful.” She stepped inside the cramped hall and put the basket down.

The other woman beamed, but then her nose wrinkled as Anna moved past her. “Dear, there’s a peculiar odor coming from…” She trailed off and stared at the top of Anna’s head. “Why are you wearing wet leaves in your hat?”

Anna grimaced and reached up to feel. “I’m afraid I had a slight mishap on the high road.”

“A mishap?” Mother Wren dropped the spoon in her agitation. “Are you hurt? Why, your gown looks as if you’ve wallowed in a pigsty.”

“I’m quite all right; just a bit damp.”

“Well, we must get you into dry clothes at once, dear. And your hair—Fanny!” Mother Wren interrupted herself to call in the general direction of the kitchen. “We’ll have to wash it. Your hair, I mean. Here, let me help you up the stairs. Fanny!”

A girl, all elbows, reddened hands, and topped by a mass of carroty hair, sidled into the hall. “Wot?”

Mother Wren paused on the stairs behind Anna and leaned over the rail. “How many times have I told you to say, ‘Yes, ma’am’? You’ll never become a maid in a big house if you don’t speak properly.”

Fanny stood blinking up at the two women. Her mouth was slightly ajar.

Mother Wren sighed. “Go put a pot of water on to heat. Miss Anna will be washing her hair.”

The girl scurried into the kitchen, then popped her head back out. “Yes, mum.”

The top of the steep stairs opened onto a miniscule landing. To the left was the elder woman’s room; to the right, Anna’s. She entered her small room and went straight to the mirror hanging over the dresser.

“I don’t know what the town is coming to,” her mother-in-law panted behind her. “Were you splashed by a carriage? Some of these mail-coach drivers are simply irresponsible. They think the entire road is theirs alone.”

“I couldn’t agree with you more,” Anna replied as she peered at her reflection. A faded wreath of dried apple blossoms was draped over the edge of the mirror, a memento from her wedding. “But it was a single horseman in this case.” Her hair was a rat’s nest, and there were still spots of mud on her forehead.

“Even worse, these gentlemen on horses,” the older woman muttered. “Why, I don’t think they’re able to control their animals, some of them. Terribly dangerous. They’re a menace to woman and child.”

“Mmm.” Anna took off her shawl, bumping her shin against a chair as she moved. She glanced around the tiny room. This was where she and Peter had spent all four years of their marriage. She hung her shawl and hat on the hook where Peter’s coat used to be. The chair where he once piled his heavy law books now served as her bedside table. Even his hairbrush with the few red hairs caught in its bristles had long ago been packed away.

“At least you saved the herring.” Mother Wren was still fretting. “Although I don’t think a dunking in mud will have improved its flavor.”

“No doubt,” Anna replied absently. Her eyes returned to the wreath. It was crumbling. No wonder, since she had been widowed six years. Nasty thing. It would be better in the garden rubbish pile. She tossed it aside to take down later.

“Here, dear, let me help you.” Mother Wren began unhooking the dress from the bottom. “We’ll have to sponge this right away. There’s quite a bit of mud around the hem. Perhaps if I applied a new trim…” Her voice was muffled as she bent over. “Oh, that reminds me, did you sell my lace to the milliner?”

Anna pushed the dress down and stepped out of it. “Yes, she quite liked the lace. She said it was the finest she’d seen in a while.”

“Well, I have been making lace for almost forty years.” Mother Wren tried to look modest. She cleared her throat. “How much did she give you for it?”

Anna winced. “A shilling sixpence.” She reached for a threadbare wrap.

“But I worked five months on it,” Mother Wren gasped.

“I know.” Anna sighed and took down her hair. “And, as I said, the milliner considered your work to be of the finest quality. It’s just that lace doesn’t fetch very much.”

“It does once she puts it on a bonnet or a dress,” Mother Wren muttered.

Anna grimaced sympathetically. She took a bathing cloth off a hook under the eaves, and the two women descended the stairs in silence.

In the kitchen, Fanny hovered over a kettle of water. Bunches of dried herbs hung from the black beams, scenting the air. The old brick fireplace took up one whole wall. Opposite was a curtain-framed window that overlooked the back garden. Lettuce marched in a frilled chartreuse row down the tiny plot, and the radishes and turnips had been ready for a week now.

Mother Wren set a chipped basin on the kitchen table. Worn smooth by many years of daily scrubbing, the table took pride of place in the middle of the room. At night they pushed it to the wall so that the little maid could unroll a pallet in front of the fire.

Fanny brought the kettle of water. Anna bent over the basin, and Mother Wren poured the water on her head. It was lukewarm.

Anna soaped her hair and took a deep breath. “I’m afraid we will have to do something about our financial situation.”

“Oh, don’t say there will be more economies, dear,” Mother Wren moaned. “We’ve already given up fresh meat except for mutton on Tuesdays and Thursdays. And it’s been ages since either of us has had a new gown.”

Anna noticed that her mother-in-law didn’t mention Fanny’s upkeep. Although the girl was supposedly their maid-cum-cook, in reality she was a charitable impulse on both their parts. Fanny’s only relative, her grandfather, had died when she was ten. At the time, there’d been talk in the village of sending the girl to a poorhouse, but Anna had moved to intervene, and Fanny had been with them ever since. Mother Wren had hopes of training her to work in a large household, but so far her progress was slow.

“You’ve been very good about the economies we’ve made,” Anna said now as she worked the thin lather into her scalp. “But the investments Peter left us aren’t doing as well as they used to. Our income has decreased steadily since he passed away.”

“It’s such a shame he left us so little to live on,” Mother Wren said.

Anna sighed. “He didn’t mean to leave such a small sum. He was a young man when the fever took him. I’m sure had he lived, he would’ve built up the savings substantially.”

In fact, Peter had improved their finances since his own father’s death shortly before their marriage. The older man had been a solicitor, but several ill-advised investments had landed him deeply in debt. After the wedding, Peter had sold the house he had grown up in to pay off the debts and moved his new bride and widowed mother into the much-smaller cottage. He had been working as a solicitor when he’d become ill and died within the fortnight.

Leaving Anna to manage the little household on her own. “Rinse, please.”

A stream of chilly water poured over her nape and head. She felt to make sure no soap remained, then squeezed the excess water from her hair. She wrapped a cloth around her head and glanced up. “I think I should find a position.”

“Oh, dear, surely not that.” Mother Wren plopped down on a kitchen chair. “Ladies don’t work.”

Anna felt her mouth twitch. “Would you prefer I remain a lady and let us both starve?”

Mother Wren hesitated. She appeared to actually debate the question.

“Don’t answer that,” Anna said. “It won’t come to starvation anyway. However, we do need to find a way to bring some income into the household.”

“Perhaps if I were to produce more lace. Or, or I could give up meat entirely,” her mother-in-law said a little wildly.

“I don’t want you to have to do that. Besides, Father made sure I had a good education.”

Mother Wren brightened. “Your father was the best vicar Little Battleford ever had, God rest his soul. He did let everyone know his views on the education of children.”

“Mmm.” Anna took the cloth off her head and began combing out her wet hair. “He made sure I learned to read and write and do figures. I even have a little Latin and Greek. I thought I’d look tomorrow for a position as a governess or companion.”

“Old Mrs. Lester is almost blind. Surely her son-in-law would hire you to read—” Mother Wren stopped.

Anna became aware at the same time of an acrid scent in the air. “Fanny!”

The little maid, who had been watching the exchange between her employers, yelped and ran to the pot of stew over the fire. Anna groaned.

Another burned supper.

FELIX HOPPLE PAUSED before the Earl of Swartingham’s library door to take stock of his appearance. His wig, with two tight sausage curls on either side, was freshly powdered in a becoming lavender shade. His figure—quite svelte for a man of his years—was highlighted by a puce waistcoat edged with vining yellow leaves. And his hose had alternating green and orange stripes, handsome without being ostentatious. His toilet was perfection itself. There was really no reason for him to hesitate outside the door.

He sighed. The earl had a disconcerting tendency to growl. As estate manager of Ravenhill Abbey, Felix had heard that worrisome growl quite a bit in the last two weeks. It’d made him feel like one of those unfortunate native gentlemen one read about in travelogues who lived in the shadows of large, ominous volcanoes. The kind that might erupt at any moment. Why Lord Swartingham had chosen to take up residence at the Abbey after years of blissful absence, Felix couldn’t fathom, but he had the sinking feeling that the earl intended to remain for a very, very long time.

The steward ran a hand down the front of his waistcoat. He reminded himself that although the matter he was about to bring to the earl’s attention was not pleasant, it could in no way be construed as his own fault. Thus prepared, he nodded and tapped at the library door.

There was a pause and then a deep, sure voice rasped, “Come.”

The library stood on the west side of the manor house, and the late-afternoon sun streamed through the large windows that took up nearly the entire outside wall. One might think this would make the library a sunny, welcoming room, but somehow the sunlight was swallowed by the cavernous space soon after it entered, leaving most of the room to the domain of the shadows. The ceiling—two stories high—was wreathed in gloom.

The earl sat behind a massive, baroque desk that would’ve dwarfed a smaller man. Nearby, a fire attempted to be cheerful and failed dismally. A gigantic, brindled dog sprawled before the hearth as if dead. Felix winced. The dog was a mongrel mix that included a good deal of mastiff and perhaps some wolfhound. The result was an ugly, mean-looking canine he tried hard to avoid.

He cleared his throat. “If I could have a moment, my lord?”

Lord Swartingham glanced up from the paper in his hand. “What is it now, Hopple? Come in, come in, man. Sit down while I finish this. I’ll give you my attention in a minute.”

Felix crossed to one of the armchairs before the mahogany desk and sank into it, keeping an eye on the dog. He used the reprieve to study his employer for an idea of his mood. The earl scowled at the page in front of him, his pockmarks making the expression especially unattractive. Of course, this was not necessarily a bad sign. The earl habitually scowled.

Lord Swartingham tossed aside the paper. He took off his half-moon reading glasses and threw his considerable weight back in his chair, making it squeak. Felix flinched in sympathy.

“Well, Hopple?”

“My lord, I have some unpleasant news that I hope you will not take too badly.” He smiled tentatively.

The earl stared down his big nose without comment.

Felix tugged at his shirt cuffs. “The new secretary, Mr. Tootleham, had word of a family emergency that forced him to hand in his resignation rather quickly.”

There was still no change of expression on the earl’s face, although he did begin to drum his fingers on the chair arm.

Felix spoke more rapidly. “It seems Mr. Tootleham’s parents in London have become bedridden by a fever and require his assistance. It is a very virulent illness with sweating and purging, qu-quite contagious.”

The earl raised one black eyebrow.

“I-in fact, Mr. Tootleham’s two brothers, three sisters, his elderly grandmother, an aunt, and the family cat have all caught the contagion and are utterly unable to fend for themselves.” Felix stopped and looked at the earl.

Silence.

Felix wrestled valiantly to keep from babbling.

“The cat?” Lord Swartingham snarled softly.

Felix started to stutter a reply but was interrupted by a bellowed obscenity. He ducked with newly practiced ease as the earl picked up a pottery jar and flung it over Felix’s head at the door. It hit with a tremendous crash and a tinkle of falling shards. The dog, apparently long used to the odd manner in which Lord Swartingham vented his spleen, merely sighed.

Lord Swartingham breathed heavily and pinned Felix with his coal-black eyes. “I trust you have found a replacement.”

Felix’s neckcloth felt suddenly tight. He ran a finger around the upper edge. “Er, actually, my lord, although, of course, I’ve searched qu-quite diligently, and indeed, all the nearby villages have been almost scoured, I haven’t—” He gulped and courageously met his employer’s eye. “I’m afraid I haven’t found a new secretary yet.”

Lord Swartingham didn’t move. “I need a secretary to transcribe my manuscript for the series of lectures given by the Agrarian Society in four weeks,” he enunciated awfully. “Preferably one who will stay more than two days. Find one.” He snatched up another sheet of paper and went back to reading.

The audience had ended.

“Yes, my lord.” Felix bounced nervously out of the chair and scurried toward the door. “I’ll start looking right away, my lord.”

Lord Swartingham waited until Felix had almost reached the door before rumbling, “Hopple.”

On the point of escape, Felix guiltily drew back his hand from the doorknob. “My lord?”

“You have until the morning after tomorrow.”

Felix stared at his employer’s still-downcast head and swallowed, feeling rather like that Hercules fellow must have on first seeing the Augean stables. “Yes, my lord.”

EDWARD DE RAAF, the fifth Earl of Swartingham, finished reading the report from his North Yorkshire estate and tossed it onto the pile of papers, along with his spectacles. The light from the window was fading fast and soon would be gone. He rose from his chair and went to look out. The dog got up, stretched, and padded over to stand beside him, bumping at his hand. Edward absently stroked its ears.

This was the second secretary to decamp in the dark of night in so many months. One would think he was a dragon. Every single secretary had been more mouse than man. Show a little temper, a raised voice, and they scurried away. If even one of his secretaries had half the pluck of the woman he had nearly run down yesterday… His lips twitched. He hadn’t missed her sarcastic reply to his demand of why she was in the road. No, that madam stood her ground when he blew his fire at her. A pity his secretaries couldn’t do the same.

He glowered out the dark window. And then there was this other nagging… disturbance. His boyhood home was not as he remembered it.

True, he was a man now. When he had last seen Ravenhill Abbey, he’d been a stripling youth mourning the loss of his family. In the intervening two decades, he had wandered from his northern estates to his London town house, but somehow, despite the time, those two places had never felt like home. He had stayed away precisely because the Abbey would never be the same as when his family had lived here. He’d expected some change. But he’d not been prepared for this dreariness. Nor the awful sense of loneliness. The very emptiness of the rooms defeated him, mocking him with the laughter and light that he remembered.

The family that he remembered.

The only reason he persisted in opening up the mansion was because he hoped to bring his new bride here—his prospective new bride, pending the successful negotiation of the marital contract. He wasn’t going to repeat the mistakes of his first, short marriage and attempt to settle elsewhere. Back then, he’d tried to make his young wife happy by remaining in her native Yorkshire. It hadn’t worked. In the years since his wife’s untimely death, he’d come to the conclusion that she wouldn’t have been happy anywhere they’d chosen to make their home.

Edward pushed away from the window and strode toward the library doors. He would start as he meant to; go on and live at the Abbey; make it a home again. It was the seat of his earldom and where he meant to replant his family tree. And when the marriage bore fruit, when the halls once again rang with children’s laughter, surely then Ravenhill Abbey would feel alive again.

Now, all three of the duke’s daughters were equally fair. The eldest had hair of deepest pitch that shone with blue-black lights; the second had fiery locks that framed a milky-white complexion; and the youngest was golden, both of face and form, so that she seemed bathed in sunlight. But of these three maidens, only the youngest was blessed with her father’s kindness. Her name was Aurea….

—from The Raven Prince

Who would have guessed that there was such a paucity of jobs for genteel ladies in Little Battleford? Anna had known that it wouldn’t be easy to find a position when she left the cottage this morning, but she’d started with some hope. All she required was a family with illiterate children needing a governess or an elderly lady in want of a wool-winder. Surely this was not too much to expect?

Evidently it was.

It was midafternoon now. Her feet ached from trudging up and down muddy lanes, and she didn’t have a position. Old Mrs. Lester had no love of literature. Her son-in-law was too parsimonious to hire a companion in any case. Anna called round on several other ladies, hinting that she might be open to a position, only to find they either could not afford a companion or simply did not want one.

Then she’d come to Felicity Clearwater’s home.

Felicity was the third wife of Squire Clearwater, a man some thirty years older than his bride. The squire was the largest landowner in the county besides the Earl of Swartingham. As his wife, Felicity clearly considered herself the preeminent social figure in Little Battleford and rather above the humble Wren household. But Felicity had two girls of a suitable age for a governess, so Anna had called on her. She’d spent an excruciating half hour feeling her way like a cat walking on sharp pebbles. When Felicity had caught on to Anna’s reason for visiting, she’d smoothed a pampered hand over her already immaculate coiffure. Then she’d sweetly enquired about Anna’s musical knowledge.

The vicarage had never run to a harpsichord when Anna’s family had occupied it. A fact Felicity knew very well, since she’d called there on several occasions as a girl.

Anna had taken a deep breath. “I’m afraid I don’t have any musical ability, but I do have a bit of Latin and Greek.”

Felicity had flicked open a fan and tittered behind it. “Oh, I do apologize,” she’d said when she’d recovered. “But my girls will not be. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...