- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

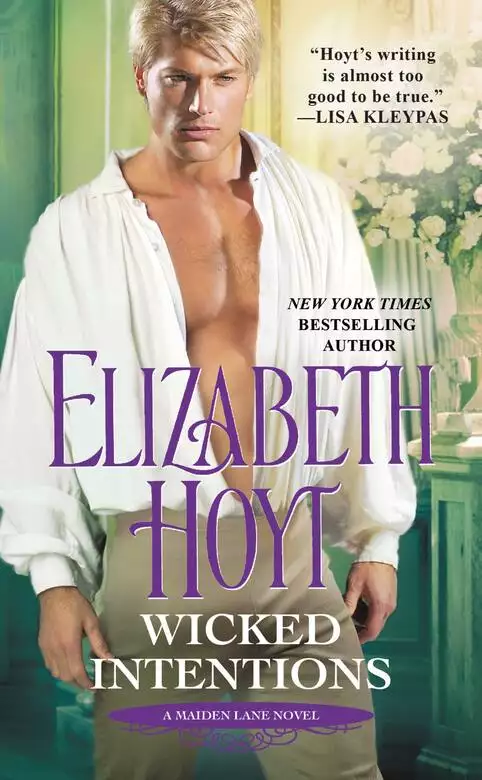

From the New York Times bestselling author of To Desire a Devil comes this thrilling tale of danger, desire, and dark passions.

A MAN CONTROLLED BY HIS DESIRES . . .

Infamous for his wild, sensual needs, Lazarus Huntington, Lord Caire, is searching for a savage killer in St. Giles, London's most notorious slum. Widowed Temperance Dews knows St. Giles like the back of her hand-she's spent a lifetime caring for its inhabitants at the foundling home her family established. Now that home is at risk . . .

A WOMAN HAUNTED BY HER PAST . . .

Caire makes a simple offer-in return for Temperance's help navigating the perilous alleys of St. Giles, he will introduce her to London's high society so that she can find a benefactor for the home. But Temperance may not be the innocent she seems, and what begins as cold calculation soon falls prey to a passion that neither can control-one that may well destroy them both.

A BARGAIN NEITHER COULD REFUSE

Release date: July 17, 2010

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Wicked Intentions

Elizabeth Hoyt

Lockedheart….

—from King Lockedheart

LONDON

FEBRUARY 1737

A woman abroad in St. Giles at midnight was either very foolish or very desperate. Or, as in her own case, Temperance Dews

reflected wryly, a combination of both.

“’Tis said the Ghost of St. Giles haunts on nights like this,” Nell Jones, Temperance’s maidservant, said chattily as she

skirted a noxious puddle in the narrow alley.

Temperance glanced dubiously at her. Nell had spent three years in a traveling company of actors and sometimes had a tendency

toward melodrama.

“There’s no ghost haunting St. Giles,” Temperance replied firmly. The cold winter night was frightening enough without the

addition of specters.

“Oh, indeed, there is.” Nell hoisted the sleeping babe in her arms higher. “He wears a black mask and a harlequin’s motley

and carries a wicked sword.”

Temperance frowned. “A harlequin’s motley? That doesn’t sound very ghostlike.”

“It’s ghostlike if he’s the dead spirit of a harlequin player come back to haunt the living.”

“For bad reviews?”

Nell sniffed. “And he’s disfigured.”

“How would anyone know that if he’s masked?”

They were coming to a turn in the alley, and Temperance thought she saw light up ahead. She held her lantern high and gripped

the ancient pistol in her other hand a little tighter. The weapon was heavy enough to make her arm ache. She could have brought

a sack to carry it in, but that would’ve defeated its purpose as a deterrent. Though loaded, the pistol held but one shot,

and to tell the truth, she was somewhat hazy on the actual operation of the weapon.

Still, the pistol looked dangerous, and Temperance was grateful for that. The night was black, the wind moaning eerily, bringing

with it the smell of excrement and rotting offal. The sounds of St. Giles rose about them—voices raised in argument, moans

and laughter, and now and again the odd, chilling scream. St. Giles was enough to send the most intrepid woman running for

her life.

And that was without Nell’s conversation.

“Horribly disfigured,” Nell continued, ignoring Temperance’s logic. “’Tis said his lips and eyelids are clean burned off, as if he

died in a fire long ago. He seems to grin at you with his great yellow teeth as he comes to pull the guts from your belly.”

Temperance wrinkled her nose. “Nell!”

“That’s what they say,” Nell said virtuously. “The ghost guts his victims and plays with their entrails before slipping away

into the night.”

Temperance shivered. “Why would he do that?”

“Envy,” Nell said matter-of-factly. “He envies the living.”

“Well, I don’t believe in spirits in any case.” Temperance took a breath as they turned the corner into a small, wretched

courtyard. Two figures stood at the opposite end, but they scuttled away at their approach. Temperance let out her breath.

“Lord, I hate being abroad at night.”

Nell patted the infant’s back. “Only a half mile more. Then we can put this wee one to bed and send for the wet nurse in the

morning.”

Temperance bit her lip as they ducked into another alley. “Do you think she’ll live until morning?”

But Nell, usually quite free with her opinions, was silent. Temperance peered ahead and hurried her step. The baby looked

to be only weeks old and had not yet made a sound since they’d recovered her from the arms of her dead mother. Normally a

thriving infant was quite loud. Terrible to think that she and Nell might’ve made this dangerous outing for naught.

But then what choice had there been, really? When she’d received word at the Home for Unfortunate Infants and Foundling Children

that a baby was in need of her help, it had still been light. She’d known from bitter experience that if they’d waited until

morn to retrieve the child, it would either have expired in the night from lack of care or would’ve already been sold for

a beggar’s prop. She shuddered. The children bought by beggars were often made more pitiful to elicit sympathy from passersby.

An eye might be put out or a limb broken or twisted. No, she’d really had no choice. The baby couldn’t wait until morning.

Still, she’d be very happy when they made it back to the home.

They were in a narrow passage now, the tall houses on either side leaning inward ominously. Nell was forced to walk behind

Temperance or risk brushing the sides of the buildings. A scrawny cat snaked by, and then there was a shout very near.

Temperance’s steps faltered.

“Someone’s up ahead,” Nell whispered hoarsely.

They could hear scuffling and then a sudden high scream.

Temperance swallowed. The alley had no side passages. They could either retreat or continue—and to retreat meant another twenty

minutes added to their journey.

That decided her. The night was chilly, and the cold wasn’t good for the babe.

“Stay close to me,” she whispered to Nell.

“Like a flea on a dog,” Nell muttered.

Temperance squared her shoulders and held the pistol firmly in front of her. Winter, her youngest brother, had said that one

need only point it and shoot. That couldn’t be too hard. The light from the lantern spilled before them as she entered another

crooked courtyard. Here she stood still for just a second, her light illuminating the scene ahead like a pantomime on a stage.

A man lay on the ground, bleeding from the head. But that wasn’t what froze her—blood and even death were common enough in

St. Giles. No, what arrested her was the second man. He crouched over the first, his black cloak spread to either side of him like the wings of a great bird of prey. He

held a long black walking stick, the end tipped with silver, echoing his hair, which was silver as well. It fell straight

and long, glinting in the lantern’s light. Though his face was mostly in darkness, his eyes glinted from under the brim of

a black tricorne. Temperance could feel the weight of the stranger’s stare. It was as if he physically touched her.

“Lord save and preserve us from evil,” Nell murmured, for the first time sounding fearful. “Come away, ma’am. Swiftly!”

Thus urged, Temperance ran across the courtyard, her shoes clattering on the cobblestones. She darted into another passage

and left the scene behind.

“Who was he, Nell?” she panted as they made their way through the stinking alley. “Do you know?”

The passage let out suddenly into a wider road, and Temperance relaxed a little, feeling safer without the walls pressing

in.

Nell spat as if to clear a foul taste from her mouth.

Temperance looked at her curiously. “You sounded like you knew that man.”

“Knew him, no,” Nell replied. “But I’ve seen him about. That was Lord Caire. He’s best left to himself.”

“Why?”

Nell shook her head, pressing her lips firmly together. “I shouldn’t be speaking about the likes of him to you at all, ma’am.”

Temperance let that cryptic comment go. They were on a better street now—some of the shops had lanterns hanging by the doors,

lit by the inhabitants within. Temperance turned one more corner onto Maiden Lane, and the foundling home came within sight.

Like its neighbors, it was a tall brick building of cheap construction. The windows were few and very narrow, the doorway

unmarked by any sign. In the fifteen precarious years of the foundling home’s existence, there had never been a need to advertise.

Abandoned and orphaned children were all too common in St. Giles.

“Home safely,” Temperance said as they reached the door. She set down the lantern on the worn stone step and took out the

big iron key hanging by a cord at her waist. “I’m looking forward to a dish of hot tea.”

“I’ll put this wee one to bed,” Nell said as they entered the dingy little hall. It was spotlessly clean, but that didn’t

hide the fallen plaster or the warped floorboards.

“Thank you.” Temperance removed her cloak and was just hanging it on a peg when a tall male form appeared at the far doorway.

“Temperance.”

She swallowed and turned. “Oh! Oh, Winter, I did not know you’d returned.”

“Obviously,” her younger brother said drily. He nodded to the maidservant. “A good eventide to you, Nell.”

“Sir.” Nell curtsied and looked nervously between brother and sister. “I’ll just see to the, ah, children, shall I?”

And she fled upstairs, leaving Temperance to face Winter’s disapproval alone.

Temperance squared her shoulders and moved past her brother. The foundling home was long and narrow, squeezed by the neighboring

houses. There was one room off the small entryway. It was used for dining and, on occasion, receiving the home’s infrequent

important visitors. At the back of the house were the kitchens, which Temperance entered now. The children had all had their

dinner promptly at five o’clock, but neither she nor her brother had eaten.

“I was just about to make some tea,” she said as she went to stir the fire. Soot, the home’s black cat, got up from his place

in front of the hearth and stretched before padding off in search of mice. “There’s a bit of beef left from yesterday and

some new radishes I bought at market this morning.”

Behind her Winter sighed. “Temperance.”

She hurried to find the kettle. “The bread’s a bit stale, but I can toast it if you like.”

He was silent and she finally turned and faced the inevitable.

It was worse than she feared. Winter’s long, thin face merely looked sad, which always made her feel terrible. She hated to

disappoint him.

“It was still light when we set out,” she said in a small voice.

He sighed again, taking off his round black hat and sitting at the kitchen table. “Could you not wait for my return, sister?”

Temperance looked at her brother. Winter was only five and twenty, but he bore himself with the air of a man twice his age.

His countenance was lined with weariness, his wide shoulders slumped beneath his ill-fitting black coat, and his long limbs

were much too thin. For the last five years, he had taught at the tiny daily school attached to the home.

On Papa’s death last year, Winter’s work had increased tremendously. Concord, their eldest brother, had taken over the family

brewery. Asa, their next-eldest brother, had always been rather dismissive of the foundling home and had a mysterious business

of his own. Both of their sisters, Verity, the eldest of the family, and Silence, the youngest, were married. That had left

Winter to manage the foundling home. Even with her help—she’d worked at the home since the death of her husband nine years

before—the task was overwhelming for one man. Temperance feared for her brother’s well-being, but both the foundling home

and the tiny day school had been founded by Papa. Winter felt it was his filial duty to keep the two charities alive.

If his health did not give out first.

She filled the teakettle from the water jar by the back door. “Had we waited, it would have been full dark with no assurance

that the babe would still be there.” She glanced at him as she placed the kettle over the fire. “Besides, have you not enough

work to do?”

“If I lose my sister, think you that I’d be more free of work?”

Temperance looked away guiltily.

Her brother’s voice softened. “And that discounts the lifelong sorrow I would feel had anything happened to you this night.”

“Nell knew the mother of the baby—a girl of less than fifteen years.” Temperance took out the bread and carved it into thin

slices. “Besides, I carried the pistol.”

“Hmm,” Winter said behind her. “And had you been accosted, would you have used it?”

“Yes, of course,” she said with flat certainty.

“And if the shot misfired?”

She wrinkled her nose. Their father had brought up all her brothers to debate a point finely, and that fact could be quite

irritating at times.

She carried the bread slices to the fire to toast. “In any case, nothing did happen.”

“This night.” Winter sighed again. “Sister, you must promise me you’ll not act so foolishly again.”

“Mmm,” Temperance mumbled, concentrating on the toast. “How was your day at the school?”

For a moment, she thought Winter wouldn’t consent to her changing the subject. Then he said, “A good day, I think. The Samuels

lad remembered his Latin lesson finally, and I did not have to punish any of the boys.”

Temperance glanced at him with sympathy. She knew Winter hated to take a switch to a palm, let alone cane a boy’s bottom.

On the days that Winter had felt he must punish a boy, he came home in a black mood.

“I’m glad,” she said simply.

He stirred in his chair. “I returned for luncheon, but you were not here.”

Temperance took the toast from the fire and placed it on the table. “I must have been taking Mary Found to her new position.

I think she’ll do quite well there. Her mistress seemed very kind, and the woman took only five pounds as payment to apprentice

Mary as her maid.”

“God willing she’ll actually teach the child something so we won’t see Mary Found again.”

Temperance poured the hot water into their small teapot and brought it to the table. “You sound cynical, brother.”

Winter passed a hand over his brow. “Forgive me. Cynicism is a terrible vice. I shall try to correct my humor.”

Temperance sat and silently served her brother, waiting. Something more than her late-night adventure was bothering him.

At last he said, “Mr. Wedge visited whilst I ate my luncheon.”

Mr. Wedge was their landlord. Temperance paused, her hand on the teapot. “What did he say?”

“He’ll give us only another two weeks, and then he’ll have the foundling home forcibly vacated.”

“Dear God.”

Temperance stared at the little piece of beef on her plate. It was stringy and hard and from an obscure part of the cow, but

she’d been looking forward to it. Now her appetite was suddenly gone. The foundling home’s rent was in arrears—they hadn’t

been able to pay the full rent last month and nothing at all this month. Perhaps she shouldn’t have bought the radishes, Temperance

reflected morosely. But the children hadn’t had anything but broth and bread for the last week.

“If only Sir Gilpin had remembered us in his will,” she murmured.

Sir Stanley Gilpin had been Papa’s good friend and the patron of the foundling home. A retired theater owner, he’d managed

to make a fortune on the South Sea Company and had been wily enough to withdraw his funds before the notorious bubble burst.

Sir Gilpin had been a generous patron while alive, but on his unexpected death six months before, the home had been left floundering.

They’d limped along, using what money had been saved, but now they were in desperate straits.

“Sir Gilpin was an unusually generous man, it would seem,” Winter replied. “I have not been able to find another gentleman

so willing to fund a home for the infant poor.”

Temperance poked at her beef. “What shall we do?”

“The Lord shall provide,” Winter said, pushing aside his half-eaten meal and rising. “And if he does not, well, then perhaps

I can take on private students in the evenings.”

“You already work too many hours,” Temperance protested. “You hardly have time to sleep as it is.”

Winter shrugged. “How can I live with myself if the innocents we protect are thrown into the street?”

Temperance looked down at her plate. She had no answer to that.

“Come.” Her brother held out his hand and smiled.

Winter’s smiles were so rare, so precious. When he smiled, his entire face lit as if from a flame within, and a dimple appeared

on one cheek, making him look boyish, more his true age.

One couldn’t help smiling back when Winter smiled, and Temperance did so as she laid her hand in his. “Where will we go?”

“Let us visit our charges,” he said as he took a candle and led her to the stairs. “Have you ever noticed that they look quite

angelic when asleep?”

Temperance laughed as they climbed the narrow wooden staircase to the next floor. There was a small hall here with three doors

leading off it. They peered in the first as Winter held his candle high. Six tiny cots lined the walls of the room. The youngest

of the foundlings slept here, two or three to a cot. Nell lay in an adult-sized bed by the door, already asleep.

Winter walked to the cot nearest Nell. Two babes lay there. The first was a boy, red-haired and pink-cheeked, sucking on his

fist as he slept. The second child was half the size of the first, her cheeks pale and her eyes hollowed, even in sleep. Tiny

whorls of fine black hair decorated her crown.

“This is the baby you rescued tonight?” Winter asked softly.

Temperance nodded. The little girl looked even more frail next to the thriving baby boy.

But Winter merely touched the baby’s hand with a gentle finger. “How do you like the name Mary Hope?”

Temperance swallowed past the thickness in her throat. “’Tis very apt.”

Winter nodded and, with a last caress for the tiny babe, left the room. The next door led to the boys’ dormitory. Four beds

held thirteen boys, all under the age of nine—the age when they were apprenticed out. The boys lay with limbs sprawled, faces

flushed in sleep. Winter smiled and pulled a blanket over the three boys nearest the door, tucking in a leg that had escaped

the bed.

Temperance sighed. “One would never think that they spent an hour at luncheon hunting for rats in the alley.”

“Mmm,” Winter answered as he closed the door softly behind them. “Small boys grow so swiftly to men.”

“They do indeed.” Temperance opened the last door—the one to the girls’ dormitory—and a small face immediately popped off

a pillow.

“Did you get ’er, ma’am?” Mary Whitsun whispered hoarsely.

She was the eldest of the girls in the foundling home, named for the Whitsunday morning nine years before when she’d been

brought to the home as a child of three. Young though Mary Whitsun was, Temperance had to sometimes leave her in charge of

the other children—as she’d had to tonight.

“Yes, Mary,” Temperance whispered back. “Nell and I brought the babe home safely.”

“I’m glad.” Mary Whitsun yawned widely.

“You did well watching the children,” Temperance whispered. “Now sleep. A new day will be here soon.”

Mary Whitsun nodded sleepily and closed her eyes.

Winter picked up a candlestick from a little table by the door and led the way out of the girls’ dormitory. “I shall take

your kind advice, sister, and bid you good night.”

He lit the candlestick from his own and gave it to Temperance.

“Sleep well,” she replied. “I think I’ll have one more cup of tea before retiring.”

“Don’t stay up too late,” Winter said. He touched her cheek with a finger—much as he had the babe—and turned to mount the

stairs.

Temperance watched him go, frowning at how slowly he moved up the stairs. It was past midnight, and he would rise again before

five of the clock to read, write letters to prospective patrons, and prepare his school lessons for the day. He would lead

the morning prayers at breakfast, hurry to his job as schoolmaster, work all morning before taking one hour for a meager luncheon,

and then work again until after dark. In the evening, he heard the girls’ lessons and read from the Bible to the older children.

Yet, when she voiced her worries, Winter would merely raise an eyebrow and inquire who would do the work if not he?

Temperance shook her head. She should be to bed as well—her day started at six of the clock—but these moments by herself in

the evening were precious. She’d sacrifice a half hour’s sleep to sit alone with a cup of tea.

So she took her candle back downstairs. Out of habit, she checked to see that the front door was locked and barred. The wind

whistled and shook the shutters as she made her way to the kitchen, and the back door rattled. She checked it as well and

was relieved to see the door still barred. Temperance shivered, glad she was no longer outside on a night like this. She rinsed

out the teapot and filled it again. To make a pot of tea with fresh leaves and only for herself was a terrible luxury. Soon

she’d have to give this up as well, but tonight she’d enjoy her cup.

Off the kitchen was a tiny room. Its original purpose was forgotten, but it had a small fireplace, and Temperance had made

it her own private sitting room. Inside was a stuffed chair, much battered but refurbished with a quilted blanket thrown over

the back. A small table and a footstool were there as well—all she needed to sit by herself next to a warm fire.

Humming, Temperance placed her teapot and cup, a small dish of sugar, and the candlestick on an old wooden tray. Milk would

have been nice, but what was left from this morning would go toward the children’s breakfast on the morrow. As it was, the

sugar was a shameful luxury. She looked at the small bowl, biting her lip. She really ought to put it back; she simply didn’t

deserve it. After a moment, she took the sugar dish off the tray, but the sacrifice brought her no feeling of wholesome goodness.

Instead she was only weary. Temperance picked up the tray, and because both her hands were full, she backed into the door

leading to her little sitting room.

Which was why she didn’t notice until she turned that the sitting room was already occupied.

There, sprawled in her chair like a conjured demon, sat Lord Caire. His silver hair spilled over the shoulders of his black

cape, a cocked hat lay on one knee, and his right hand caressed the end of his long ebony walking stick. This close, she realized

that his hair gave lie to his age. The lines about his startlingly blue eyes were few, his mouth and jaw firm. He couldn’t

be much older than five and thirty.

He inclined his head at her entrance and spoke, his voice deep and smooth and softly dangerous.

“Good evening, Mrs. Dews.”

SHE STOOD WITH quiet confidence, this respectable woman who lived in the sewer that was St. Giles. Her eyes had widened at the sight of

him, but she made no move to flee. Indeed, finding a strange man in her pathetic sitting room seemed not to frighten her at

all.

Interesting.

“I am Lazarus Huntington, Lord Caire,” he said.

“I know. What are you doing here?”

He tilted his head, studying her. She knew him, yet did not recoil in horror? Yes, she’d do quite well. “I’ve come to make

a proposition to you, Mrs. Dews.”

Still no sign of fear, though she eyed the doorway. “You’ve chosen the wrong lady, my lord. The night is late. Please leave

my house.”

No fear and no deference to his rank. An interesting woman indeed.

“My proposition is not, er, illicit in nature,” he drawled. “In fact, it’s quite respectable. Or nearly so.”

She sighed and looked down at her tray, and then back up at him. “Would you like a cup of tea?”

He almost smiled. Tea? When had he last been offered something so very prosaic by a woman? He couldn’t remember.

But he replied gravely enough. “Thank you, no.”

She nodded. “Then if you don’t mind?”

He waved a hand to indicate permission.

She set the tea tray on the wretched little table and sat on the padded footstool to pour herself a cup. He watched her. She

was a monochromatic study. Her dress, bodice, hose, and shoes were all flat black. A fichu tucked in at her severe neckline,

an apron, and a cap—no lace or ruffles—were all white. No color marred her aspect, making the lush red of her full lips all

the more startling. She wore the clothes of a nun, yet had the mouth of a sybarite.

The contrast was fascinating—and arousing.

“You’re a Puritan?” he asked.

Her beautiful mouth compressed. “No.”

“Ah.” He noted she did not say she was Church of England either. She probably belonged to one of the many obscure nonconformist

sects, but then he was interested in her religious beliefs only as they impacted his own mission.

She took a sip of tea. “How do you know my name?”

He shrugged. “Mrs. Dews and her brother are well-known for their good deeds.”

“Really?” Her tone was dry. “I was not aware we were so famous beyond the boundaries of St. Giles.”

She might look demure, but there were teeth behind the prim expression. And she was quite right—he would never have heard

of her had he not spent the last month stalking the shadows of St. Giles. Stalking fruitlessly, which was why he’d followed

her home and sat before this miserable fire now.

“How did you get in?” she asked.

“I believe the back door was unlocked.”

“No, it wasn’t.” Her brown eyes met his over her teacup. They were an odd light color, almost golden. “Why are you here, Lord

Caire?”

“I wish to hire you, Mrs. Dews,” he said softly.

She stiffened and set her teacup down on the tray. “No.”

“You haven’t heard the task for which I wish to hire you.”

“It’s past midnight, my lord, and I’m not inclined to games even during the day. Please leave or I shall be forced to call

my brother.”

He didn’t move. “Not a husband?”

“I’m widowed, as I’m sure you already know.” She turned to look into the fire, presenting a dismissive profile to him.

He stretched his legs in what room there was, his boots nearly in the fire. “You’re quite correct—I do know. I also know that

you and your brother have not paid the rent on this property in nearly two months.”

She said nothing, merely sipping her tea.

“I’ll pay handsomely for your time,” he murmured.

She looked at him finally, and he saw a golden flame in those pale brown eyes. “You think all women can be bought?”

He rubbed his thumb across his chin, considering the question. “Yes, I do, though perhaps not strictly by money. And I do

not limit it to women—all men can be bought in one form or another as well. The only trouble is in finding the applicable

currency.”

She simply stared at him with those odd eyes.

He dropped his hand, resting it on his knee. “You, for instance, Mrs. Dews. I would’ve thought your currency would be money

for your foundling home, but perhaps I’m mistaken. Perhaps I’ve been fooled by your plain exterior, your reputation as a prim

widow. Perhaps you would be better persuaded by influence or knowledge or even the pleasures of the flesh.”

“You still haven’t said what you want me for.”

Though she hadn’t moved, hadn’t changed expression at all, her voice had a rough edge. He caught it only because he had years

of experience at the chase. His nostrils flared involuntarily, as if the hunter within was trying to scent her. Which of his

list had interested her?

“A guide.” His eyelids drooped as he pretended to examine his fingernails. “Merely that.” He watched her from under his brows

and saw when that lush mouth pursed.

“A guide to what?”

“St. Giles.”

“Why do you need a guide?”

Ah, this was where it got tricky. “I’m searching for… a certain person in St. Giles. I would like to interview some of the

inhabitants, but I find my search confounded by my ignorance of the area and the people and by their reluctance to talk to

me. Hence, a guide.”

Her eyes had narrowed as she listened, her fingers tapping against the teacup. “Whom do you search for?”

He shook his head slowly. “Not unless you agree to be my guide.”

“And that is all you want? A guide? Nothing else?”

He nodded, watching her.

She turned to look into the fire as if consulting it. For a moment, the only sound in the room was the snap of a piece of

coal falling. He waited patiently, caressing the silver head of his cane.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...