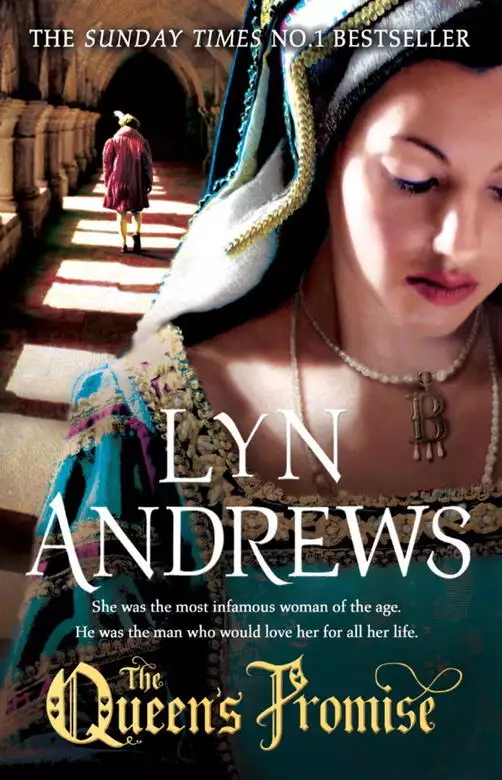

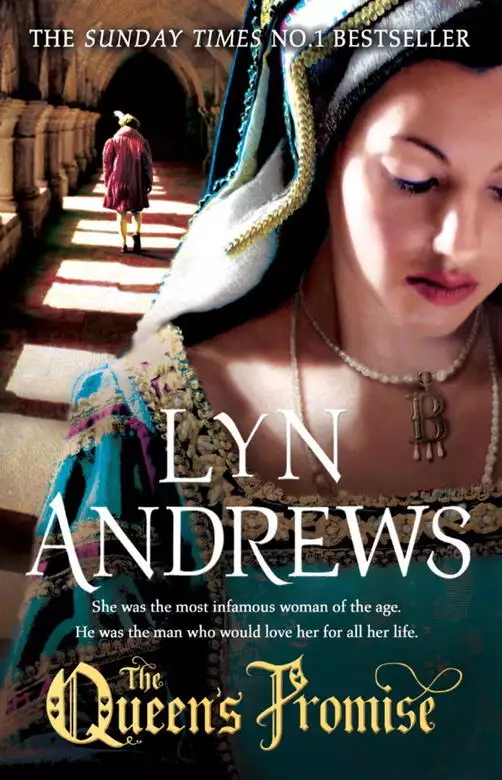

The Queen's Promise

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From bestselling author Lyn Andrews comes a compelling historical epic set at the endlessly fascinating Tudor court about the most infamous woman of the age - Anne Boleyn - and the man who loved her before she became queen.

From the moment Henry Percy, future Earl of Northumberland, glimpses the beautiful Anne Boleyn he is captivated and quickly proposes marriage Anne has been taught to use her charms to her advantage and to secure her family's position of power at court. She sees that Henry Percy's affection is sincere and agrees to marry him.

But a match of the heart has no place in a world where marriage is a political manoeuvre. Torn apart, the lovers are exiled to separate ends of the kingdom. For Henry a lifetime of duty awaits, while he remains true to the only woman he will ever love. But he is not the only man to be bewitched by Anne. And when King Henry VIII determines to make her his queen, the course of history is changed for ever...

Release date: September 27, 2012

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 369

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Queen's Promise

Lyn Andrews

Wressle Castle, Yorkshire

IT WAS UNSEASONABLY HOT for May. The late-morning sun blazed down from a perfect sky, casting parts of the crenellated battlements into deep shade

whilst illuminating others with its brilliant rays. The air was still and heavy and sound carried clearly: the drone of bees

in the blossoms on the fruit trees in the orchards beyond the courtyard wall; the scrape of a shovel against stone as a boy

mucked out in the stable block; and the faint, mournful lowing of cattle in the distant water meadows beside the River Derwent.

Muted by the thickness of the castle walls, the voices of servants could be heard as the hour for dinner approached.

Sir William Percy swatted away the flies that, attracted by the steaming pile of dung from his horse and the beads of sweat

that stood out on his brow, were annoying him. He leaned forward in the saddle, his gaze fixed on the figure of his young

nephew some yards away in the centre of the tilt yard. The boy was clad in a short dark blue tunic bordered with gold thread.

Around his waist he wore a belt of Spanish leather and his hands were tightly clasped around the hilt of a sword, the blade

of which was equal to his height. A slight, pale child with short brown hair covered by a hood of mail, he fixed his eyes

on his opponent, a lad not much older than himself.

‘Again, Henry! Again! Feign to the left this time and put more of your weight behind the thrust.’ Sir William shouted the

instructions with a note of impatience in his voice.

The child struggled to raise the weapon but with an effort managed to do so; he doggedly swung it in an arc towards his opponent,

who parried the blow easily, causing the child to lose his balance. He staggered and then fell heavily, dropping the sword.

A cloud of dust rose to sting his eyes and cling to his lips. Spitting the dirt from his mouth he drew the sleeve of his tunic

across his face, trying to ignore the pain that was searing his cheek and blinking rapidly to stem the tears of humiliation

and frustration that filled his brown eyes. The sword was too heavy, too large and unwieldy. His arms were arching and he

could feel the sweat trickling down his neck beneath the tight hood of metal links. He lacked neither the courage nor the

will for combat, just the strength and the skill.

Sir William leaned back, shook his head and sighed heavily before turning to his older brother, Henry Algernon Percy, Fifth

Earl of Northumberland, who was seated beside him on a fine chestnut gelding, its saddlecloth and trappings also of blue and

gold damask. ‘There are times when I think his heart is just not in it, Henry. He makes little improvement despite my tutoring

and the hours spent in practice.’

His brother frowned, shifting his position slightly and adjusting his dark blue velvet bonnet which was growing increasingly

uncomfortable in the heat. ‘He will learn, William. In time he will improve. He is five years old.’

‘And Harry “Hotspur” was eight when he accompanied his father to France as a page in the campaign against du Guesclin,’ his

brother reminded him succinctly.

Irritated by the comparison of his eldest son and heir to their illustrious ancestor, Henry Algernon flicked the rein and

turned the gelding’s head towards the stable block. ‘There are other ways of gaining esteem and favour, William. Am I not

assembling the greatest collection of literature and learning in the North? Have I not advanced our position at court; does

the King not look with affection upon our loyalty? Did our sovereign lord not choose me to escort the Princess Margaret to

her wedding with King James of Scotland?’

Sir William urged his horse forward, his lips set in a line of disapproval. He did not agree with his brother. The Earl’s

ways were not the ways of the Border. In his view his brother had spent too much time and money in London, courting the favour

of a suspicious and watchful King. He well remembered how much money it had cost to escort King Henry’s daughter, Princess

Margaret Tudor, to her wedding, for his brother had spared no expense. Accompanied by a dozen knights, the Northumberland

Herald, the Percy Herald and four hundred mounted gentlemen all clad in velvet and damask bearing the Percy arms of the crescent

and manacles, the Earl had led the procession wearing a surcoat of crimson velvet, the collar and sleeves of which had been

thickly encrusted with precious stones and pearls set in goldsmith’s work. His black velvet boots bore his stirrups of gold, his horse’s crimson velvet saddlecloth had been bordered with gilt and reached to the ground.

He’d heard it said the Earl had looked more like a prince than a subject and that was a comment that had reached the ears

of the rapacious Henry VII, who abhorred such displays of wealth and power by a subject. In consequence – under the guise

of a wardship dispute – that display had cost the Earl a fine of ten thousand pounds. No, he did not approve of Henry Algernon’s

ways or his wasteful extravagance. And what use were fine clothes, books, manuscripts and illuminated texts in fighting the

Scots or marauding moss troopers?

‘He will have to learn, for what use is a Percy – a Warden of the Scottish Marches – if he cannot fight? Would you have the

Scots mock us? Would you have them reiving the Marches at will?’

The Earl dismounted and passed the reins to a groom. ‘I say he will learn and when the time comes he will not dishonour the name of Percy,’ he snapped. ‘Now, let us eat.’

Sir William remained silent as he followed his brother into the castle. He was a veteran of numerous violent and bloody border

campaigns and he grudgingly admitted that his brother’s courage and fighting skills could not be lightly dismissed either.

Ten years ago the Earl had led the Northern Horse in the royalist army’s victorious assault on the pretender Perkin Warbeck’s

army of rebellious Cornishmen at Blackheath, capturing the causeway at Deptford Strand. Sir William hoped that when the time

did indeed come, his young nephew would not be found wanting in courage, skill or leadership.

Blickling Hall, Norfolk

The chamber was uncomfortably hot and stuffy. Outside the sun bathed the courtyard and gardens in a golden light and sparkled

on the small diamond-shaped panes of the windows of the old manor house. The new green leaves on the trees that surrounded

the rear of the building rustled in the soft warm breeze. The scent of flowers – violets, gilly flowers and early roses –

filled the air but their perfume did not drift in through the window for no window in the chamber had been opened for days.

No sunlight penetrated the room; heavy curtains covered the windows. The tapestries and painted cloths that hung from the

walls increased the oppressive, stifling atmosphere and not even the sweet herbs that had been strewn on the rushes on the

floor could dispel the cloying odours of sweat and blood.

Her nightgown and the sheet on which she lay were soaked with perspiration; her light brown hair was plastered to her skull.

Her skin was clammy with sweat and her throat felt raw and dry. Her lips were sore and bloody for she’d bitten them as she’d

fought to stifle her cries of agony. The palms of her hands bore the deep indentations of her fingernails. As the pain diminished

she fell back on the pillows, gasping for breath.

‘Sweet Virgin! How much longer must I bear this?’ she begged.

‘Be of good cheer, my lady. It will soon be over and you can rest. Take a few sips of wine, it will help.’ Mistress Tyndall,

the midwife, held the goblet to her mouth but she shook her head, turning away.

‘I cannot. Take it away, it sickens me. It was the same when I laboured with George.’

‘I remember now, my lady. Maybe it is an omen – a good omen. Maybe the child will be another boy.’

She tried to smile but the pain tore through her again and she writhed, sinking her teeth again into her ragged bottom lip.

She was a Howard, a daughter of the Earl of Surrey, and she would not scream out in her agony . . . but it had gone on for so long now and she was close to exhaustion. Surely, surely the child

must come soon.

The pain became unbearable, as was the urge to bear down. She was being consumed by this agony, it was tearing her apart and

yet she knew she would not die from it. With a rush of blood and mucus that stained the damp sheet the child was thrust out

and she felt waves of dizziness, relief and exhaustion wash over her.

‘My lady, it is a fine healthy girl,’ Mistress Tyndall cried, lifting the baby and giving it a slap on the tiny buttocks.

The child immediately wailed loudly and fretfully. The woman laughed. ‘See how strong and lusty she is.’ The midwife tied

and cut the cord and wrapped the baby in a clean linen sheet.

The maids had gently lifted her up and slipped more pillows behind her. They stripped off her stained nightgown, bathing her

face, neck and shoulders with rose water. Then they changed the soiled bedding and dressed her in a clean, sweet-smelling

robe and Mistress Tyndall handed the baby to her. She smiled down at the little scrap of humanity in her arms. The child waved

tiny fists and briefly opened her eyes. They were dark brown and her head was covered with soft, downy hair that looked almost

black in the flickering candlelight.

‘You will send word to my lord husband?’

Mistress Tyndall nodded. ‘I have already sent a girl to find Sir Thomas and inform him of the news.’

Lady Elizabeth Boleyn nodded slowly. ‘He will perhaps be disappointed it is not another son.’

Mistress Tyndall frowned. ‘We should all praise God that the child is healthy.’

Elizabeth sighed, feeling wearied almost to death now the ordeal was over. ‘But girls are of little use to an ambitious father

and a dowry will cost him dear.’

Mistress Tyndall nodded as she went about overseeing the tidying and sweetening of the chamber. ‘There will be a goodly time

before Sir Thomas needs contemplate that, my lady. Have you a name for her?’

Lady Boleyn nodded. ‘She will be christened Anne.’

1513

Alnwick Castle, Northumberland

WINTER SEEMED TO COME very early to the northern counties of England and particularly to Northumberland, Henry thought as he sat shivering on his

horse in the inner courtyard of the castle. At eleven he was still a slender boy with a pale, often wan, complexion, and he

would have preferred to have stayed at Wressle, his father’s castle further south beyond the city of York. It was far more

comfortable than Alnwick, whose sandstone walls towered above and around him, glittering in the frosty November morning.

Alnwick was an impregnable fortress built on a natural bluff above the River Aln and the small town that bore the same name.

The curtain wall was ten feet thick in parts and rose to forty feet in height. The turrets of its many towers were adorned

with heraldic shields and medieval figures of knights and men-at-arms carved from stone which, from a distance, looked lifelike and were intended to deter potential raiders, be

they marauding Scots or the thieves and brigands that infested the valleys of Redesdale and Tynedale to the north-west. Alnwick

was impressive, Henry thought, but it was far from comfortable.

He pulled the collar of his heavy, fur-lined cloak up around his ears and then reached out to pat the neck of Curtall, who

was becoming restless, pawing the ground with an iron-shod forefoot. He glanced around at the two dozen men who waited with

him. Their horses also becoming restive; metal bits and curb chains clinked as heads were tossed and their breath rose like

steam from a cauldron into the cold air. The riders were all his father’s men, their weather-beaten faces grim beneath thick

cloth hats and hoods of chain mail. Born and bred in Northumberland, they were marcher men all. Beneath their heavy felt cloaks

they wore padded tunics and steel breastplates. They were armed with swords and short battle-axes; heavy leather gauntlets

protected their hands and high leather boots their feet. They waited impassively and in silence and he felt safe within their

company.

Frowning, he tried to sit taller in the saddle and control the shivering, which was compounded of both cold and apprehension.

He hadn’t wanted to be part of this expedition – he was content to sit with his books in the comparative warmth and comfort

of his chamber above the gatehouse – but his father had insisted.

‘By God’s blood! Is it a weakling I’ve bred?’ the Earl had demanded angrily when he’d tried to excuse himself. ‘When I am

dead the Wardenship of the Marches will be yours. As Earl of Northumberland it will be your duty to administer justice on behalf of King Henry. Since William of Normandy came to this

land we have protected the King’s realm against the Scots. It’s time you looked to your duty and responsibilities! You are

eleven years of age, Harry Hotspur was of that age when he was knighted by King Richard and at twelve his father granted him

the honour of leading the victorious assault on the castle at Berwick.’

Henry had ceased to protest but he still felt ill at ease and apprehensive. He was fully aware that he did not have the warlike

temperament of his illustrious ancestor, who had fought the Scots at Otterburn two hundred years ago and become the most acclaimed

knight in the realm. His younger brothers Thomas and Ingram did. Arrogant and strutting, they both would have relished this

opportunity; instead they were inside the castle sulking and posturing because they were not accompanying their father this

time. Now a hard day’s ride lay ahead, followed by what would be a very cold and cheerless night spent in Ros Castle, which

was little more than a fortified tower house near Chillingham, before their return to Alnwick.

The looting, burning and murdering by the brigands of Redesdale, behaviour known throughout the Borders as ‘reiving’, had

increased of late and the Earl was determined to show by force of arms that the House of Percy would no longer stand for such

flagrant disregard of the law. In the minds of the inhabitants of this wild and inhospitable part of the country London was

far away and King Henry VIII but a vague, distant figurehead. It was the Earl they feared rather than the King.

The comparative quiet of the crisp November morning was disrupted by the sudden clattering of hooves on the cobbles as a groom

led out the Earl’s destrier. Seventeen hands in height at the shoulder and as black as the night, it looked gigantic beside

Curtall and the mounts of the marcher men. It was truly a magnificent beast, young Henry thought. His father strode out behind,

preparing to mount, and the familiar mixture of respect and fear filled him at the sight: ‘Henry the Magnificent’ inspired

awe; a tall, strong man on whose features were etched grim determination and pride. His clothes were the most fashionable

and expensive to be seen outside of London. He was dressed for hard riding in a dark green doublet, slashed to show the white

shirt he wore beneath, and padded breeches. Italian leather boots encased his muscular legs and over his fine clothes he wore

a cape of soft russet leather lined with sable fur. His hat was of black velvet – a flat bonnet adorned with a black feather

– which would be covered by the furred hood of his cape when the journey commenced. At his side hung his two-handed sword

of tempered steel and upon the horse’s saddle was strapped a battle-axe.

The Earl acknowledged Branxton, his sergeant, with a brief nod and then stared down at his eldest son. Henry tried hard not

to quail beneath that hard, speculative gaze.

‘Ride close to Branxton,’ his father instructed him sharply before urging his horse forward. ‘Come, we have delayed too long,’

he commanded.

They moved off under the iron-studded portcullis, the horses’ hooves clattering upon the wooden drawbridge, and rode quickly

through the parkland that surrounded the castle. Riding next to Branxton Henry realised they were heading in a north-westerly direction towards the Cheviot Hills and the border with Scotland. A border where an almost constant state of

war had existed for hundreds of years.

He felt the warmth begin to creep slowly back into his limbs as eventually the moorland stretched out before them, deep purple

in places where the heather grew thickest but grey and stark in the distance where the hills rose, etched against a pale duck-egg-blue

sky.

Although he rode well it was far from easy going for frost had turned the ground iron hard. By mid-morning a wind had sprung

up and the watery sun was hidden behind sullen, lowering clouds the colour of gunmetal. The first icy drops of rain stung

his cheeks and the biting wind made his eyes water. Thomas would be welcome to this, he thought miserably as the rain became

heavier and began to soak into his cape. He would be chilled to the bone and aching all over before this day was out and then

no doubt he would be laid low with an ague to which he was prone. Ahead of him rode his father, his back erect, his head unbent

in the face of the elements, as though disdainful of them. The soldiers, familiar with both the terrain and the harsh climate,

kept up with the Earl’s relentless pace, hunched and silent in their saddles.

At noon, to Henry’s relief, they reached the village of Hepburn and the Earl halted. It wasn’t a very prepossessing place,

he thought, peering through the curtain of rain; it was poor and miserable, a huddle of daub and wattle cottages, their thatched

roofs held down securely against the winter gales by boulders and ropes. A road that was little more than a muddy track led

to a barn of sorts and the ubiquitous midden heap, but a few yards beyond that there did appear to be an inn.

‘Branxton, ale and such food as they can furnish and water and fodder for the horses,’ the Earl instructed curtly as he dismounted

a little stiffly.

‘And a good fire, my lord. Lord Henry’s face is the colour of parchment,’ the sergeant informed his master in a low voice.

When they reached the inn, Henry slid slowly down from Curtall’s saddle, his knees buckling with the numbness of fatigue.

The man nearest him held out his arm and the boy clutched it tightly to steady himself.

‘A pot of spiced ale will soon warm you, Lord Henry,’ he said, not unkindly, for he thought the boy looked ill and wondered

if the rigours of this expedition would be too much for him. The young lord was reputed to be of a sickly disposition, unlike

both his brothers Thomas and Ingram.

The inn comprised one long, dark, low-ceilinged room, the roughly hewn beams black with smoke from the fire that burned at

the far end, the floor hard packed earth. The furnishings consisted of a few crude benches and stools; empty upturned barrels

served as tables. Upon being informed of the identity of his illustrious guests the landlord hastily beat his wife and daughter

into a flurry of activity to prepare the small room beside their kitchen for the Earl and the young lord.

As the landlord ushered them in, grovelling before them, the Earl looked askance at the old and rancid rushes on the floor,

which were probably alive with vermin and lice, the hastily cleared table devoid of any covering and the two battered stools.

Henry, despite his wretchedness, wrinkled his nose in distaste at the smell of sour ale, stale food and sweat, animal fat

and dung that seemed to permeate the room, the latter wafting in from the midden heap behind the building. With the dubious benefits of a pot of hot spiced ale and the warmth from the fire, however, he began to feel a little better.

The landlord’s daughter, an unkempt slattern overcome with awe to the point of dumbness, served them with flat, coarse trencher

loaves and thick wedges of strong-smelling cheese. This, her father explained with abject humility, was all a poor but God-fearing

man such as himself could provide. Had his lordship sent word ahead he would have killed some chickens and his wife would

have cooked them.

‘Plain fare will suffice. You will be paid for your hospitality,’ the Earl informed him, before slicing up the bread with

the jewelled knife he had drawn from his belt.

It was a brief respite but when they departed an hour later Henry felt stronger. The rain had ceased and the entire population

of the village had turned out. Many had never seen the Earl before and were staring in open astonishment at the richness of

his clothes and the magnificence of the horse’s saddle and trappings. Men doffed shapeless hats; women bobbed curtsies while

small, grubby children clung wide-eyed to their stained skirts. A ragged cheer, instigated by the landlord of the inn went

up as the Earl and his men prepared to depart. Henry was still cold and stiff but his teeth had ceased to chatter, he wasn’t

shivering so hard and his belly was full.

They resumed their journey, which took them with each passing mile ever closer to the notorious valley of Redesdale. The landscape

grew more desolate. The few trees that had survived were stunted and twisted by the prevailing winds. Steep hills strewn with

huge boulders slowed them down and a chill numbness again penetrated Henry’s bones. His head had begun to ache.

‘My lord! Look! Smoke! Over to the left!’ Branxton cried.

The Earl reined in his horse and peered in the direction of the sergeant-at-arms’s outstretched finger. Many miles away on

the distant horizon, thick black smoke rose in a column and then appeared to be absorbed by the heavy cinereous clouds.

‘The work of those murdering bastards of Redesdale, I’ll warrant!’ Branxton muttered grimly. He had only contempt for the

thieves and cowards who skulked in these remote valleys and terrorised the poor peasants.

The Earl did not reply but his mouth was set in a hard line and his eyes were the colour of flint as he turned his horse’s

head in the direction of the steep, gravel-strewn path that led towards the column of smoke.

Henry’s throat felt dry and his heart lurched. He just wanted to go home; to crawl into a soft bed, pull the thick warm blankets

around him, lay his aching head on a soft pillow of goose down and have his mother soothe and fuss over him. With an effort

he straightened his back and swallowed hard. He was not a mewling child. He must put aside all the discomforts. He must not

shame his father or his ancestors. He was a Percy of Northumberland, the great border lords who upheld the law and kept the

King’s peace. He must remember that above all else – whatever lay ahead.

Redesdale, Northumberland

‘WILL, LAD, TAKE IN that bundle of kindling to your mother. I’ll chop up this blackthorn trunk; it will burn well when seasoned. It’s not often

such a stroke of luck falls to us.’

Will Chatton grinned at his father, squinting up through the unkempt fringe of brown hair that was always falling into his

hazel eyes. His rough homespun tunic, tied around the waist with twine, and the dun-coloured leggings, also bound with twine

around his calves and ankles, did little to keep out the cold blasts of wind that blew down the valley. His feet were encased

in badly fitting, patched old boots and his hands were rough, chapped and ingrained with dirt. He was a hardy if rather skinny

lad of eleven and had never in his life known the comfort of warm, serviceable clothes, good boots or a full belly. He worked

hard helping his father to wrest a meagre living from the poor patch of land that surrounded the cottage and barn, which nestled in a hollow at the base of a rocky outcrop.

‘I’ll help you drag it into the barn out of the weather,’ he offered.

‘After you’ve done as you are bid. Your mother will need that kindling for the fire if we’re to have any hot food inside us

today,’ Jed Chatton reminded him. ‘Get off with you, lad.’ Then he picked up the axe and turned his attention to the fallen

blackthorn. The stunted old tree had come down in the wind two nights ago and he’d thanked the Blessed Virgin for such good

fortune. It was hard, back-breaking work scratching a living in this barren country. Times had been better some years ago

when they’d had a cow, a sow and her litter and some sheep and goats but they’d all been taken from them. All that was left

now were a few scrawny chickens, he thought bitterly.

‘Here’s the kindling, Ma. What be there for the dinner?’ Will asked as he hauled the bundle of twigs into the single room

where his mother sat at a bench scraping and chopping the few vegetables she’d pulled from the stony garden patch beside the

barn earlier. The smoke from the fire had blackened the squat stone walls; the floor was strewn with reeds gathered from the

edge of one of the many burns that coursed down the valley. The one small, unglazed window let in little light and the air

was dank and chilly. A pile of dried bracken in one corner served as a bed for them all, with a few sacks as bedding. Rushes

dipped in animal fat gave them scant light at night for even cheap tallow candles were beyond their means.

Will grinned at the antics of the two young bairns squabbling beside the open hearth, over which was suspended a small black pot of steaming water. John, his brother, was seven and Margaret, or ‘Meggie’ as he called her, was five.

‘Vegetable broth and I’ve a few handfuls of barley to thicken it, but it’s the last of it,’ his mother informed him. She sighed

heavily. It wasn’t much for the only hot meal of the day, barely enough to keep body and soul together, and no coarse bread

to go with it. ‘Would you go out and try to snare a coney, Will?’

He nodded. ‘I will, Ma, after I’ve helped Da to drag the trunk into the barn.’ He grinned at her, pushing his hair out of

his eyes. ‘You hear that, Meggie? We’ll have a great fire this Christmas.’

Mary Chatton smiled tiredly at him. He was a good lad, he worked hard and seldom complained. But her smile faded and a worried

frown creased her brow as she heard shouts coming from outside. ‘Go and see who that be, Will!’ she urged, getting to her

feet and pulling her coarse wool shawl tightly around her thin shoulders.

Will felt a shiver of fear run through him as he ran to the door for travellers were few and not always welcome. Then he cried

out as he saw the band of mounted men emerging from the track and heading rapidly toward the cottage. ‘Da! Da! What be they

coming here for now?’ He ran to where his father stood beside the tree trunk, gripping the axe tightly. Jed Chatton’s thin,

sallow face was flushed with anger but there was fear, too, in his eyes.

‘We’ll find out soon enough, lad,’ he said grimly as the group grew closer. There were six men mounted on small, sturdy, shaggy

ponies. He knew them well enough. They were all villainous-looking individuals, their hair and beards long and matted. They wore jerkins of leather over rough woollen shirts. Three of them wore cloaks of a green and brown woven tartan

over their jerkins and all were armed with knives and swords. They drew to a halt a few paces away and two of them dismounted.

The bigger and more thickset of the pair grinned at Jed, revealing blackened teeth. A jagged scar ran from the corner of his

mouth to his ear.

‘Good day to you, Farmer Chatton! It’s time for the dues to be paid to us,’ he announced.

‘What dues be they?’ Jed asked sullenly.

‘For our protection should the Scots come raiding across the border.’

‘We’ve seen no Scots in these parts for two years and more,’ Will retorted, stepping closer to his father and wishing he had

some sort of weapon, if only a stout stave. He hated these men, as did every poor farmer and labourer for mil

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...