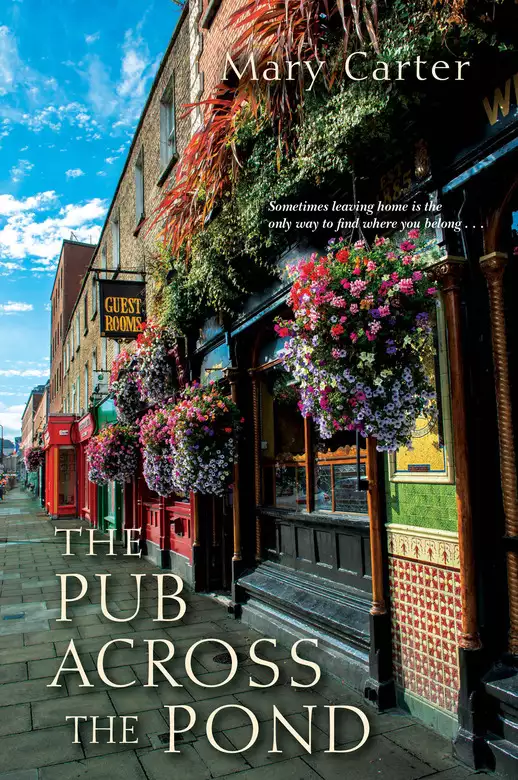

The Pub across the Pond

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Sometimes leaving home is the only way to find where you truly belong.

Carlene Rivers is many things. Dutiful, reliable, kind. Lucky? Not so much. At thirty, she’s living a stifling existence in Cleveland, Ohio. Then one day, Carlene buys a raffle ticket. The prize: a pub on the west coast of Ireland. Carlene is stunned when she wins. Everyone else is stunned when she actually goes.

As soon as she arrives in Ballybeog, Carlene is smitten, not just by the town’s beguiling mix of ancient and modern but by the welcome she receives. In this small town near Galway Bay, strife is no stranger, strangers are family, and no one is ever too busy for a cup of tea or a pint. And though her new job presents challenges—from a meddling neighbor to the pub’s colorful regulars—there are compensations galore. Like the freedom to sing, joke, and tell stories and, in doing so, find her own voice. And in her flirtation with Ronan McBride, the pub’s charming, reckless former owner, she just may find the freedom to follow where impulse leads and trust her heart—and her luck—for the very first time.

Release date: May 26, 2011

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Pub across the Pond

Mary Carter

Hopeless romantic, they call Katie. Katie agrees with all but the hopeless bit. She likes to think of herself as an optimist, even if it’s only true about 10 percent of the time. She’s twenty years of age, but nobody thinks of Katie McBride as grown-up, least of all herself. She looks around the pub, demanding an audience. Guests are still piling in, shedding their winter coats, revealing long satin dresses that will shimmer when the ladies dance and smartly pressed suits the men only wear for weddings and wakes. Women discreetly slip off their heels and massage their toes, men loosen their ties, their belts, and their wallets, and then finally their tongues. The band is lively and drunk. They’ve yet to start playing.

“A fairy tale,” Katie adds, with a loud sigh.

“Only you would call that ordeal a fairy tale,” Siobhan says, slapping her handbag on the counter and eyeing me. She thinks that one sultry look from her will be enough to send me running. And let me tell ye something. It works. Siobhan’s the oldest, the only redhead of the sisters, and practical about most things, especially love. In trounces the other four McBride girls, and whether by habit or coincidence, they sit down in order of their birth. From youngest to oldest it goes: Katie, Sarah, Liz, Clare, Anne, and Siobhan.

At the end of the bar, and no relation to the girls, sits Riley, whose real age is a bit of a mystery all right, but he’s at least a thousand years old in drinking age, and more of a fixture at Uncle Jimmy’s than the stool he’s perched on. He leans in conspiratorially and winks at the girls.

“So?” he says. “What was the result?” Even I move in to hear the answer.

“The result?” Katie says. “Why, what a way to put it.”

“Did the groom flee the scene?” a voice calls from the doorway. Laughter rolls forth, I must admit, even from me. Ah, but there’s no harm in it, we all love the bride.

“It ’twasn’t him that flew out of the church, it ’twas her,” another voice adds. The laughter doubles, and there are a few cheers, mostly from the women. Katie has her audience now. Her broad smile is lit from underneath by one of the dozen tea candles that float the length of the bar like lilies on a pond.

Into the mix slips a young German man. He looks like a student. He’s wearing denim trousers and a striped sweater, and he has an oversized backpack strapped to him. In his right hand, he holds a long piece of rope. Just about enough to hang yourself with. We don’t have too many high bridges around these parts, so students under stress get creative. He stands sideways at the edge of the bar like a puppy trying to squeeze himself into another’s litter. He orders a pint of Guinness. The chin-wagging momentarily halts, partly so I can take care of him, partly because everyone wants to ask him about the fecking rope but we’re all too fecking polite. In addition to his pint, he orders a shot of whiskey, then another shot of whiskey, then another shot of whiskey. He drinks them without ever letting go of the rope.

“Woman trouble?” I ask him. When you’re holding rope, no use taking the long way to the point. The young man nods. I pour him another whiskey. Everyone is looking at him. He has a square jaw, high cheekbones, and black eyelashes so thick that even I notice. It looks like two daddy longlegs superglued themselves just below his bushy eyebrows. His hair is fair and cropped short, and in the dim light of the pub I can’t really tell what color his eyes are. Dark, I would say they are dark, all right. Dark eyes for a dark horse. Now that I look at him, I would’ve pegged him as a wrist cutter or a jumper. Just goes to show, you never know, do ye?

“I love Lady Gaga,” the German says as if it’s just occurred to him. His voice fills our little pub. He puts his hand over his heart. “When I see Lady Gaga, everything is all right.” I nod and smile, the two biggest tools of the trade. A tear comes into his eye—looks like we’ve got a squaller. Alcohol affects everyone differently. Some people get in fights, some take off their clothes and knock boots with strangers, others have a good cry. When it comes to the ladies, I prefer the ones who like to lose their knickers, but not as much as I hate seeing a grown man cry.

“Some days, Lady Gaga is the only reason I don’t hang myself,” yer man continues.

“Well, here’s another reason for ye,” I say, setting another pint in front of him. I turn to Katie and whisper, “Who’s Lady Gaga?” Katie tells me she’s a singer and turns back to the suicidal student. She starts introducing everyone in the entire pub. It takes a while, especially when she starts saying where they live and who their young ones are, and gives a quick update on the status of their occupations, hobbies, living situations, health, recent deaths, births, or graduations, and lastly an update on their romantic entanglements. When she’s done the suicidal student looks all glassy-eyed, blinks his spider lashes slowly, and he tells us his name is The David. That’s how he says it, all right.

“I am The David.”

“Boy George thinks Lady Gaga is weird,” Sarah says out of nowhere. Sarah’s an avid reader, always has the latest tabloid clutched in her hand. The David looks stricken. “After one of his concerts she asked him to sign her vagina,” Sarah continues. “He signed her hat instead.”

“Are you on holiday, then?” Siobhan asks the man.

“University,” The David said. I knew it, but I keep my gob shut. A humble man eats more pie.

“Galway?” I ask. The David nods.

“But now I’m thinking of killing myself,” he says. None of us are surprised, but we do a good job of hiding it. Most of us anyway. Riley is too old to hide anything. He points at the rope.

“I think it’s a bit too short to do the job,” he says. “If ye like, I’ve got a bigger piece that’ll do ye.”

“D’mind him,” Katie says. “We’ll sort ye out.”

“Cheer up, things will get worse,” Siobhan says.

“Just keep thinking of Lady Gaga’s vagina,” I say. “Shite. I mean her hat.” The David nods, but tightens the grip on his rope. I don’t know what it is, but I’m starting to like this lad.

“Why do you want to kill yourself?” Liz asks.

“He already told us,” Anne says. “Woman trouble.”

“You think you have woman trouble,” Sarah says. “Try growing up with these five.”

“D’mind her,” Katie says. “Never give up on love. Ever. Do you hear? We have a love story that might cheer you up.”

“Ah, bollix,” Riley says. He bangs his pint on the bar. Beer sloshes over the edge.

“Mind your pint,” I say. “Yer wastin’ resources.” Riley lowers his head and hides his face behind his Guinness.

“Which love story are ye on about?” Liz pipes in.

“Is there more than one?” The David asks.

“Depends how you look at it,” Liz says. “Right?” Like all good middle children, she and her fraternal twin, Clare, are dutiful, exact, and the self-appointed diplomats of the lot. Always mad to get the details right. In other words, right pains in the arse.

“I’ve been married forty-six years,” Riley said. “Now that’s love.”

“Not when you’ve spent forty-five of them sitting right here,” I say. Riley pretends he didn’t hear me and turns to The David.

“Would you look after a woman for forty-six years?” Riley asks.

“I wouldn’t look after you for forty-six minutes,” Anchor says. I turn, startled. He’s sitting in the mix, drinking his pint, happy as a clam. He’s such a big man, it’s hard to figure how half the time I forget he’s there.

“Forty-six years,” The David says politely. “What’s your secret?”

“Even if you come home intoxicated, always come home with something for her,” Riley says. The David nods.

“The clap doesn’t count,” Anchor says. I shush him with a look. You can’t let the young lads get too fresh, even if they aren’t so young anymore, and even though Riley’s too hard of hearing to cop on to the slag. I too wonder when the last time was that Riley brought something home for the missus, but once again I keep my gob shut.

“Can we get back to our love story, like?” Clare says.

“Better get us another pint, then,” Anchor says. He holds up his glass, which is half-full by my account, but of course when it comes to the pint, most lads around here say it’s half-empty. By the time he takes his last sup, he’ll be expecting a new one. I’m happy to oblige.

“Get us all one,” Anne says.

“I’ll just have a mineral,” Liz says.

“Good girl,” I say.

“Good girl?” Anne says. “She downed seven glasses of champagne before the bride walked down the aisle.”

“Walked the plank is more like it,” Sarah says. The girls all laugh at the same time. I’ve got to tell you, when they all go at once, they’d bounce the bubbles out of a glass of champagne. I can’t imagine Ballybeog without the half dozen. Sometimes I feel lucky just to be in their presence, and I realize there are millions of people who will never meet these girls, never hear them laugh at the same time, and I can’t help but think, those poor fucking bastards.

“I only drank six glasses,” Liz says when their laughter ebbs. “The first one never counts.”

“I’ll drink hers,” Sarah says.

“Why are ye all here?” Riley says. He looks bewildered, as if he’s just awoken from a long nap.

“We’re waiting for the bride,” Clare reminds him. I set down a fresh round of pints. “From the beginning, pet,” I say.

“I just want to drink in peace,” Riley says. A collective “Shut yer gob” rises from behind him. The crowd moves in even closer. After all, besides the whiskey, and the beer, and the music, and the games, and the races, and the rain, this is why we gather. We gather after weddings. We gather after wakes. Saint Stephen’s Day, Saint Patrick’s Day, Saturday. Monday through Friday. Sunday after mass. We come to celebrate. Birthdays. Births. We come for gossip. We come on rainy days, we come on sunny days. Cloudy days too, plenty of those. And don’t forget windy days, and calm days, and slightly breezy days. Terrific storms. The calms before. Squalls. Wives sometimes come to drag husbands home. A few come to sip tea and listen to the music. But most of all, we gather for this, the stories. There’s nothing we love more than a good story. And so far, this is not one of them.

“What’re you on about over there?” Mike Murphy, the local guard (that’s police officer to you Yanks) and banjo player, asks. He’s warming up his instrument in his left hand while holding his pint in his right.

“A love story,” The David says.

“Right, right,” Murphy says. “Time for our break.” He motions to the rest of the band, and they join our little cluster.

Katie looks at her sisters. “I’m not sure where to start,” she says.

“Start where all good love stories begin,” Siobhan says.

“Paris?” The David asks.

“Rome?” someone else ventures. “Venice? Las Vegas?”

“No,” Siobhan says. “With a good woman and a fucked-up man.”

Ronan McBride leaned forward and rested his elbows on his knees. His right foot continuously tapped the ground, funneling all the energy in his body through his bouncing leg. He gripped his cards underneath the table. Across from him, Uncle Joe reclined in his chair. His right leg was crossed over his left, a cigarette dangled from the corner of his mouth, and he held his cards loosely in front of him, like a fan. The friendly game of poker, five-card draw, was going on its thirteenth hour.

In the beginning there were two tables of ten players. Around one A.M. it dwindled to one table of ten. As men lost, they smoked their last cigarette, swallowed the dregs of their pints, and stayed to watch. Nobody dared go home. Not when Ronan McBride and his uncle Joe were still at the table. Not when they could recoup some of their losses by betting on who was going to take the pot, and certainly not when the pot was up to fifteen thousand. Ronan was a bigger gambler, but Joe, a businessman and a teetotaler, was well suited to take him on. It was hard to believe they were related. Joe ran the general shop next door and hardly ever set foot in the pub.

In the center of the table, crumpled bills lay on top of each other like a massive pileup in a rugby game. They were out of cash and had switched to using bingo chips. It was never supposed to get up this high—it was five thousand when it came down to the two of ’em, and Joe was willing to keep the pot as it was, but Ronan had to push it.

Ronan tossed his faded yellow chip into the pot. “Twenty thousand,” he said. He could feel his mates behind him: a chorus of shuffles, and grunts, and murmurs. He wanted to yell at them to shut their pieholes, but he didn’t want to give anything away. He had four aces. Two on the deal, and two more sweet babies on the draw. It was a sure winner. He almost felt sorry for his uncle. Not sorry enough to stop. Uncle Joe had never given him a break, had never given his father a break, argued with him over the property until the day their da died, and even after, even at his father’s wake, Joe was still onto Ronan to sell him the pub. He never understood his father’s love of the drink, or the craic, or even the money that could be made from a pub.

Joe gave Jimmy grief over every twig or stone that landed on his side of the property line. He reported infractions to the guards every chance he got. His mother thought Uncle Joe had driven his father straight to the grave. Besides the drinking, and the smoking, and the fact that he never turned down a good feed, she was probably right; Joe was the one left standing.

But Ronan would take his father’s short, boisterous life over his uncle’s nervous, plodding existence any day. And he had four aces. No, he wouldn’t feel sorry for Joe, not after his crass comments at his father’s wake. He could still feel Joe’s arm around him, his breath stinking of tea. He wouldn’t even drink a pint to the oul fella.

“What are you going to do now, lad?” Joe said at the wake. Ronan looked at his pint, held it up by way of an answer. “I mean about the pub,” Joe said. “I can take it off your hands.” And then, by God if he didn’t start in on turning the pub into a spa with sunbeds. Sunbeds. At his own brother’s wake. Sunbeds, in fecking Ireland.

That’s the beauty of it, Joe said. Pale, sun-deprived, Irish women would go mental over it. They’d be millionaires. Ballybeog had enough pubs. Uncle Joe had been thinking about this for a while. He’d purchased one sunbed, and it had been sitting in the back of his truck for months. Ronan told him he should just drive it directly to these sun-deprived women, whoever they were, but Joe said he didn’t have the time, and besides, he needed a place for the sunbeds; one wouldn’t make a profit, but think what he could do with twenty!

Like Ronan was going to let his father’s pub become a roasting pit for the sun-obsessed. If they wanted the sun, they should move out of fecking Ireland. Besides, sunbeds gave you cancer. Ronan lit another cigarette and waited for Uncle Joe to react to his raise. Uncle Joe would take his sweet old time, as always. Ronan glanced with disgust at the overflowing ashtray. He smoked too much, he always smoked too many fags when he played cards. Declan quietly moved in, cleared the empty pint glasses, and replaced the ashtrays. Thanks be to God, Ronan didn’t want to look at the evidence, not stacked up against Joe’s little cuppa tea.

Four aces. Four aces. Four aces.

Joe dug in his pockets. He was such a thin man, and he was starting to look old. Was he shrinking? He and his father had never looked alike, his father so tall, so large, so full of life. Like two balloons, only somebody popped Joe and sucked all the air out of him. How was it that he was the one still alive?

Joe took out a set of keys. He was going home. This would all be over. He could probably sense Ronan’s unbelievable luck. Four aces. Maybe Ronan had signaled his hand, shaking his damn leg. Well, it was all he could do to contain himself. He was too wrecked to keep up his poker face. He smiled and reached for the pot. Joe’s hand slapped over his with surprising force. “Settle,” Joe said. It was the same tone he’d used with Ronan when he was a child. “Settle.” Ronan snatched his hand back and tucked it under his armpit. Joe dangled the keys over the center of the table. They swirled clockwise over the pot like a dousing rod sensing water. The men watching moved in, mesmerized. Once, around, twice around, three times around before they dropped with a clink.

Ronan stared at the keys. He looked at Uncle Joe. Ronan could hear his best friend, Anchor, standing behind him, smacking his lips. Anchor always smacked his lips when he was excited, which is why he was out of the game after the first round.

“What’s that now?” Ronan said, pointing to the keys. “Your truck?” Joe’s truck was a rusty old thing, not worth piss, even with the sunbed thrown in.

“Keys to the shop,” Joe said.

“Keys to the shop,” Ronan repeated.

“Now you put in the keys to the pub,” Joe said. The lads reacted behind him. They said, “oh man,” and “oh fuck,” and “no fucking way,” and he couldn’t tell who was saying what because the loudest voice was inside his head, and it belonged to his father.

Joe’s crafty. Did I tell ye about the time he tricked me outta me own shoes? You did, Da. Many times. They were new shoes too. I’d only worn ’em one hour. Was sent home from school for walking around in me socks. Quiet, Da. I have to focus.

Four aces. He had four aces. He had to have him beat. Joe was bluffing, or Joe thought he was bluffing. Joe never took Ronan seriously, always thought he was a fuckup, probably couldn’t imagine him with pocket aces and two more sweet babies on the draw. You did not fold with four aces. With four aces you owned the table.

Ronan studied his uncle’s face. Round, drawn, and lined like a basket. With his stick-thin body and round head, he looked like an aging lollipop. His hair was surprisingly still hanging on, soft curls that had long since turned gray and were in desperate need of a snip. Bushy eyebrows, thin lips, watchful brown eyes underneath heavy spectacles. He always looked slightly drunk—ironic wasn’t it, for a teetotaler? He looked relaxed. Too relaxed?

Ronan glanced behind the bar to see if Declan was watching. He was wiping down the bar, as if paying no attention whatsoever.

“Declan?” Ronan called.

“Yes, lad?” Declan didn’t look up, but he visibly flushed.

“Toss me the keys, will ye?” Anchor, so named because he had the strength to hold most anything down, clamped his hand down on Ronan’s shoulder.

“Roe,” he said. “Don’t.” Despite his heft, Anchor was a softy, always looking out for the lads. He worked hard, he played hard, and he’d be the first to arrive and last to leave if you ever needed anything from him. But in this case, Ronan knew he was looking out for his own self. Anchor would go mental if his local pub suddenly morphed into Tan Land. Even if the place was filled with half-naked women. As the old joke went, a gay Irishman was an Irishman who would pick pussy over a pint.

“Throw ’em,” Ronan said. Declan lifted the set of keys from the hook on the back wall and tossed them into the air. Ronan caught them in his left hand without even looking up. Had it not been such a tense moment, that kind of catch would have been cause for a celebration, and a round of shots would’ve been bought and downed. As it stood they were suddenly sober, and deathly silent. Even their cigarettes seemed to hover in midair. As Ronan gripped the keys to the pub, he and his uncle Joe stared steadily at each other from across the table.

“Wait,” Anchor said. “Just hold on.” Sweat poured into Anchor’s goatee. He adjusted his baseball cap, then held both hands out. He took his cap off, wiped his brow with his massive, freckled forearm, then put it back on. “Just hang on here,” Anchor said. He paced a stretch of floor. “This is fecking nuts. We have to have some kind of sit-down.”

“We are sitting down,” Ronan said.

“It’s not your game, lad,” Joe said.

“How about a fallback?” Anchor said.

“How’s that now?” Joe said.

I have four fucking aces, Ronan tried to convey with his eyes.

“How about—a hundred thousand euros—within a month—or you get the pub?” Anchor said. “Or shop,” he added with an apologetic glance to Ronan.

“Bollix,” Ronan said. “Leave it be.” Anchor put his hand on Ronan’s shoulder and leaned down until his breath wheezed in Ronan’s ear.

“I’m giving you a fucking fallback,” he said. “Take it.” Like Ronan would ever be able to raise a hundred thousand euros. He looked at his uncle. Joe smiled; he was thinking the same thing. Everyone is always underestimating me, he thought. Not this time.

“A hundred thousand euros within the month,” Ronan said.

“Or?” Joe said.

“Or my pub is your tanning bed,” Ronan said. The men laughed. This time, Ronan didn’t. “You want to give me the same deal?”

“No,” Joe said. “If I lose, you get the shop.”

“Fair enough,” Ronan said. This was crazy. His uncle was losing it. Maybe he was getting demented. Maybe Ronan was taking unfair advantage of an old fella. A straight flush was the only hand in the whole world that could beat four aces. Who wouldn’t bet with these odds? If Joe wasn’t bluffing, he probably had a high straight at best. Once again, Ronan almost felt sorry for him. But there was no pity in gambling, and they were all getting tired, and it was time to end this. Ronan laid down his cards in one swift smack to the table.

“Four aces,” he said. “Sorry, Joe.” The lads whooped. Anchor cried out, tried to fist-bump Ronan, but caught him in the jaw. Ronan was too psyched to feel the pain. He’d just won Uncle Joe’s shop. He didn’t even know what he’d do with it, maybe see if his mam or the half dozen wanted to run it. Joe would turn it over all right, just like Ronan would’ve turned over the pub if he lost. An Irishman always honored his bets, even the foolish ones. Anchor put both hands on Ronan’s shoulders and squeezed. It hurt like hell, but Ronan was too happy to yell. But then, something shifted. Uncle Joe fixed Ronan with a look, and instantly Ronan felt as if he’d been hit with a blast of cold air. He even looked down at his shoes, half expecting to see only socks, with holes in the big toe, laughing up at him. Joe smiled. A crafty fecking smile if Ronan ever saw one. Then, one by one, as if serving tea to the queen, Uncle Joe laid his cards on the table. As Ronan said, only one hand in the great game of poker could beat Ronan’s four aces. And when Uncle Joe laid his high straight down on the table, Ronan’s face wasn’t the only thing that was flush.

It dawned on Ronan, as he sat in his mother’s house at the kitchen table where he was reared, that given the choice, he would have rather faced a firing squad. Anchor, who had refused to leave his side since the game went down, sat across from him. Apart from occasional lip smacks, and chairs creaking as the lads shifted in their seats, the house was silent. Mary McBride was still asleep. Ronan hoped it was a good sleep; thanks to him, it could be her last good sleep for the foreseeable future. Despite the renovated living room with fireplace, and the den with a flat-screen television that Ronan built into the wall, and the screened-in porch with soothing rocking chairs, the kitchen was where everyone gravitated, no matter where else they began. It had never struck Ronan until now how white everything was. White walls, white tiled floor, white fridge, white stove, white cabinets. Except for the faded rectangular wood table where he sat, everything else was white. He’d grown up in this kitchen and he’d never really registered the shocking amount of white. It was like a celestial haven, designed to soak in the smells of home cooking and the laughter and chatter of children, and their children, and the occasional friend or neighbor who stopped in for tea. It was the heart of the house, the place where they all ran for comfort. It was fitting, then, to choose this location to break his mother’s heart.

If only he could take the night back. Guilt churned in his stomach. But who could blame him? With three aces he would have folded sure, but for the life of him he couldn’t imagine anyone folding with four aces—even those who didn’t have a bit of gambling in their blood. That was the worst bit. If he had to do it all over, he would have done the same thing. It was a nightmare, the kind you had after too much drink, the kind designed to warn him that he was gambling too much; the waking lesson: Slow down. Was he just dreaming? Unfortunately, the hangover felt real, and Anchor’s brooding presence reminded him it was all too real. Maybe he should have done this with a phone call instead.

It was too late to run now. He’d already woken up all six of his sisters, and they were on their way to Ronan’s “emergency family meeting.” In his thirty-three years, Ronan had never called an emergency family meeting. That was usually the MO of his mam and his sisters, always wanting to convalesce over some emotional upheaval. Ronan dreaded the family meetings. Five out of six sisters said they’d be there and left it at that, but Siobhan grilled him incessantly. She kept repeating, “What have you done now?” He refused to get into it on the phone. Siobhan would have been the fifth dentist, as in “four out of five dentists recommend.” Siobhan is the one fucking dentist who just can’t agree. Emergency family meetings were supposed to be treated like births in the McBride family—it was simply mandatory to show up for them, regardless of what was about to come out.

Anchor looked as if he was going to cry. Ronan only felt numb, although as the minutes ticked by, dread slowly crept in. His head was pounding, his mouth was dry, his hands were shaking. He was too hungover for this shit. When would he ever learn? This was it, this was his lesson, and by God he was going to learn it.

A pot of tea, a pitcher of milk, and a bowl of sugar sat in the middle of the table, along with nine porcelain cups on saucers and a pile of little gold spoons. In the “Tea Party from Hell” he was definitely playing the role of the Mad Hatter.

He thought about making a fry, but he knew he’d get sick. They all would. He’d put them through a lot in his lifetime, what with gambling, drinking, women, and the time he almost set fire to the shed, and the time he landed in the slammer at eighteen for drag racing, a stunt that ended with John O’Grady in traction after he smashed head-on into the town wall. And although he got out of it with nothing more than a few broken bones, John O’Grady never drove again; to this day he rode his bicycle everywhere he went. And there were many such incidents over the years to add to the list of dumb things Ronan had done.

But this was by far the dumbest. And there was no time to waste, no avoiding this one; by the time breakfast was being cleared in Ballybeog, everyone would know that Ronan McBride had fucked up once again, and this time he’d lost the family pub.

Ronan curled his fists up and stuck the right one in his mouth. Otherwise he was going to scream. He didn’t know who he dreaded facing the most, his mam or the estrogen gang, as he liked to call the half dozen. He’d disappointed them plenty over the years. Disappointed them, angered them, and at times tortured them as only a big brother could. It was still hard to believe they were all grown women now. He still saw them as little girls. Vicious, evil little girls.

He deserved whatever they were going to throw at him. He was a grown man. Grown men should not be risking the family’s livelihood in a game of cards. His mother would weep; oh God, he hated it when she cried—especially if he was to blame. She would pray too, she would pray for him, which would make it even worse. Jaysus, he didn’t think about kindness. What if they killed him with kindness? Ronan shot up from his seat. The chair squealed on the tile floor.

“I gotta get outta here,” he said. “Will you tell them?” Anchor pointed to the chair like the grim reaper. Ronan knew Anchor would physically restrain him if he tried to leave, nail his ass to the chair if he had to—he was that kind of friend. Ronan fell back into the chair, legs splayed, arms clutching his head. Then slowly, visions of racehorses circled the tracks of his thoughts.

What if he could rake in enough wins on the ponies to pay Joe the hundred thousand? He mentally jotted down names of jockeys and trainers who owed him; he’d call

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...