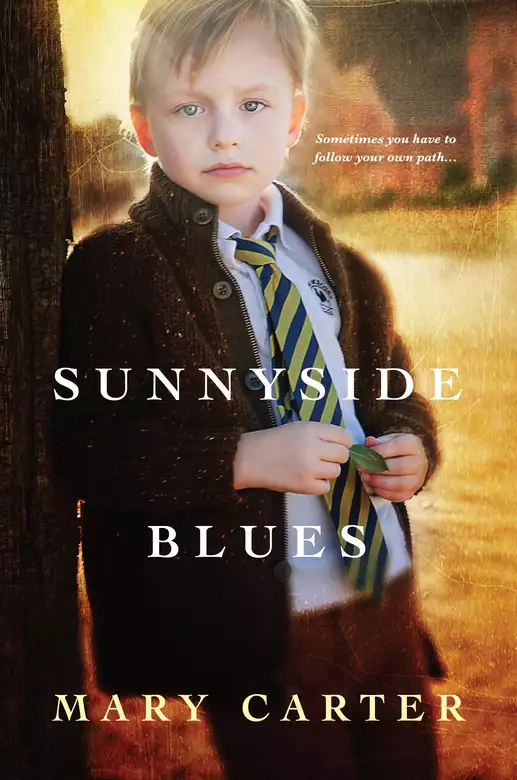

Sunnyside Blues

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In this funny, surprising, and heartfelt novel, Mary Carter explores the unlikely connection between a rootless young woman and a troubled boy--and the life-changing adventure that ensues. . . Twenty-five-year-old Andes Lane has spent nine years moving restlessly from place to place as she searches for somewhere that feels right. In the little blue houseboat bobbing on a Seattle lake, she thinks she's found it. But Andes has barely had a chance to settle in before her new life is upended by her landlord, Jay, and his son, Chase. Smart, guarded, and precocious, Chase touches a chord with Andes even as he plays on her last nerve. And though she agrees to accompany the boy on a burning quest to Sunnyside, Queens, Andes is sure it will prove fruitless--in fact, she has promised Jay it will be. But in this new, strange, unexpectedly welcoming city, both Andes and Chase will unravel their deepest secrets and darkest fears--and in the face of longed for truths, discover a freedom that feels very much like home. . . Praise for Mary Carter "The unique spin Carter takes on the familiar theme of self-discovery gives this a welcome, fresh feel." – Publishers Weekly on My Sister's Voice "Guaranteed to become one of the books on your shelf that you'll want to read again." -- The Free Lance-Star on The Pub Across the Pond

Release date: June 19, 2009

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 337

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sunnyside Blues

Mary Carter

Police Precinct

Sunnyside, Queens

There was nothing remarkable about the police interrogation room. If it were a bar, the sign on the wall would have read: TWO PERSONS MAXIMUM. Eggshell walls and a brown tile floor. Andes suddenly wished she were wearing yellow; she’d complete the metaphor: the yolk in the middle. Perhaps they were going for that effect, as if they wanted her to crack, or hatch her confession. Was there really anyone behind the one-way mirror? It too had cracks, and scratches, and particles of dust at the edges that begged for a healthy dose of Windex. Who was watching them from behind the mirror? Were they clutching little notepads and slurping strong black coffee? Andes thought she caught a whiff of it, but she hadn’t been offered any. The tape recorder was running.

“I’m telling you right now, this is one big misunderstanding. I didn’t kidnap anyone.” The officer, who looked like a kindly old grandfather, if your kindly old grandfather was the type to pick you up by your neck and give you a good shake while slowly but surely cutting off your oxygen with his gnarled knuckles, didn’t say a word. Having grown up among them, Andes was no stranger to the strong, silent type. Men with deep voices hiding behind their common-man exterior, vocal cords covered up by flannel shirts, wool scarves, and social norms. The quiet workingman, who, instead of a word, would just as soon give you a nod or a grunt, despite an eternal spring of sound, and thoughts, and jokes, hidden deep within.

Voices that could shout, sing, and speak in tongues. Voices ragged from years of working in coal mines and smoking cigarettes would somehow transform, melt into deep, dark, silk when the Lord moved on them to preach. The quiet whisper of their day voices would open up into a world of sound that both enchanted and commanded. Sitting here, on the verge of arrest, Andes could taste their voices on the tip of her tongue, catch them like snowflakes. Yet like these strong, silent men, she was suddenly at a loss for words. And it was looking like Andes, the self-proclaimed atheist, was in desperate need of an act of God.

But even if he was a religious man, it didn’t look like the Lord or anything else was going to move on the police officer sitting across from her anytime soon, so she pushed her memories aside and continued with her confession. “In the beginning, I didn’t even want to baby-sit the kid. Not that I’m not a kid person, because I am. Kids adore me, and I’ve always tolerated them extremely well.” Andes paused again just in case he wanted to jump in, lead the interrogation. She didn’t need a lawyer; she’d already told him that, this was just one big misunderstanding.

And people who asked for lawyers always looked guilty, everybody knew that. Still, Andes was keeping an ear out for what her lawyer might be objecting to if she had one. Since the officer had done little more than turn on a tape recorder and stare at her as if she were guilty until proved innocent, she’d done all the talking. Her little voice was whispering for her to stop, but her big voice plowed on.

“That sounded awful—tolerating them—didn’t it? I just mean they’ve always liked me a little bit more than I’ve liked them. But if you saw how kids take to me, you’d realize it’s not a fair comparison. Basically, they fall madly in love with me, and I fall ‘normally’ in love with them. That’s what I should have said. And I did fall madly in love with the kid. But I won’t lie; in the beginning I wanted to kill him.”

The officer raised an eyebrow. “Not literally, of course,” Andes jumped in. “That would be wrong.” The eyebrow went back down. Andes held her breath. Officer Friendly was starting to look bored. Andes wished again for a cup of coffee and this time added a chocolate cream–filled doughnut to her silent wish list as well.

“But that’s okay, because at first the kid hated me too. I know, I just told you children fall madly in love with me. Well, the kid was the exception. The first time we met, he mortified me in front of an entire dock of people. I’m sorry.” Andes apologized for the tears, now spilling out of her eyes and rolling down her cheeks.

She patted down her pockets for a tissue. Ever since she’d met the kid, she’d taken to carrying tissues in her pockets—who would have ever believed that? But she didn’t find one, he’d taken her last one, so instead she sniffed, inhaled, and topped her fantasy cup of coffee off with a shot of Baileys. But her doughnut, once sweet and decadent, now had an arsenic-centered filling. She imagined sliding it across the table to the overweight mute in blue. A glazed Trojan horse. Would she smile as he ate it? Make polite conversation? Would he recognize her betrayal seconds before the poison infiltrated his body? Poison doughnuts, poison pens, poison lipstick. Poppies, apples, parades. A harsh look from a lover. Painted toys from China. The single bite of a deadly snake. Kill him with kindness. Hello, Juliet. Wake me up when Romeo’s dead.

Andes bit her lip and tried to remember if she’d given to the policemen’s ball last year. “I’m sorry. I don’t normally cry in front of people. But the kid and I—we’ve come a long way, baby.” Andes laughed. “Oh. Don’t misunderstand that either. I don’t smoke and neither does the kid. Believe me, if I was going to start, it would have been in here (not that you would have offered me one), and if the kid ever started, I’d kill him. Not literally, of course—”

“That would be wrong,” the officer finished for her. He heaved forward and snapped off the tape recorder. Andes, who had become accustomed to him being seen and not heard, was startled when he started speaking.

“You don’t smoke?” he asked.

“No.”

“Then why all these?” The officer reached into his lap, brought up a plastic Foodtown bag, and shook the contents onto the table. Once again, he clicked Record on the tape recorder. Andes stared at her matchbook collection, obscenely splayed across the table for the world to see. She curled her fingers around the side of her chair and squeezed, fighting the urge to sweep the matchbooks onto her lap and caress them.

“Do these belong to you?” the officer asked. The tiniest flicker of apprehension manifested itself on Andes’s upper lip in the form of a little bead of sweat.

“Where did you get them?” she asked. Her voice sounded hollow and foreign in her ears. It wasn’t really what she wanted to know anyway. What she really wanted to know was what had happened to the carved wooden box in which her collection belonged. It was an old snake box Brother Elliot carved by hand forty years ago. It once housed cottonmouths, diamondbacks, and timber snakes, but Andes didn’t bother to mention that either. “Where’s the box? Didn’t they come in a wooden box?” She was aware of her voice rising and cracking, but compared to the out-and-out fit she wanted to throw, she was holding it together remarkably well. Who would take those beautiful little works of fire art out of a hand-carved box and toss them into a plastic Foodtown bag?

How many people had touched her gems, how much oil from how many fingers had seeped into the miniature works of art, marring their individuality with anonymous fingerprints? As if wanting to ratchet up her distress, the officer grabbed her matchbook from Barcelona and flicked it open with his fat thumb. He was going to ruin the cover! Had he no respect for the vibrant orange cover and tiny flamenco dancers?

“Can you please—” Andes said, bringing her hands up and clutching at air. The officer stared at her, matchbook in hand. He didn’t drop it, but at least he stopped rubbing it between his dirty fingers. “I know they might not look like much to you—”

“What? These?”

“But they are part of a collection.”

“I can see that.”

“And I would really appreciate it if you wouldn’t bend the cover like that.” There, she’d said it. Andes watched incredulity invade the officer’s face only to be swallowed up by a shake of his head. It was just as she thought; he had no clue how precious they were to her, how gorgeous, how priceless. Each little packet a painting, a purse of potential fire, the start of something, a flick, a flame. Matchbooks with names of places she’d been; the snapshot of the traveler’s life.

“You don’t mind if I…?” The officer feigned taking a match out of the book.

“I do, I do. As you can see, none of the matches have ever been used. Not a single one.” Andes, who minutes ago had been crouched over in a self-pitying pose, was now sitting ramrod straight. The officer threw the matchbook down and crossed his arms across his stonewall chest. He’d been waiting for this.

“I know that. I’ve had them thoroughly checked out.” Andes couldn’t have been more mortified if he’d passed her panties around the precinct for New York’s finest to sniff. She had to remind herself to focus on the kid. He was her first priority here, no matter what was being done to her. The officer was just trying to bait her. Calm down and focus on the kid.

“Is Chase okay? I need to know he’s okay.”

“This ain’t Guantanamo.” The officer laughed at his little joke, a chuckle that rose sharply and died down just as quickly when he realized he, alone, found it humorous.

“It’s just, the kid can really bottle it up,” Andes tried to explain. “I thought I was bad, but you’ve never seen someone stuff down feelings like that kid.”

“Ah. That explains the hunger strike.” The stress of the day, coupled with the thought of Chase going on a hunger strike for her, struck Andes as absurdly funny. This time it was her turn to laugh, and the officer’s turn to shame her into silence.

“I’m sorry. It’s just that—he never would have done anything like that before he met me. I think I’ve really helped him express his feelings in productive ways. Not that starving is necessarily productive—but it’s creative, don’t you think? And—how long have I been here?”

The officer looked at his watch. “Thirty minutes.”

“Oh. It seems like longer. He likes cheese pizza.”

“That’s what we offered him.”

“Oh. Well, did you cut it into circles?”

The officer raised an eyebrow.

“That’s the only way he’ll eat it,” Andes explained. “He’s diametrically opposed to triangles. Get it? He likes circles. Never mind. And squares are—well—square. I’ve never tried a rhombus or an octagon, so feel free, but I’m doubtful. After all, even a kid like Chase likes routine. I’m sorry, but can I have some tissues?” And maybe a fucking cup of coffee and a motherfucking glazed doughnut, you fat fuck?

The officer spread his hands out in an I-have-nothing type of way. Andes nodded and wiped the back of her hand against her nose. “I’m sorry. This has been a very emotional day. And that woman out there. I don’t care what you call her. She is not his mother. Do you hear me? She’s a horrible person who doesn’t even know that kid, let alone love him. And if you let her walk out of here with him, I’m going to the newspapers and I’m going to let everyone know that you turned an innocent ten-year-old boy over to a gold-digging crack whore.” Andes leaned down and shouted the last bit into the tape recorder before putting her head down on the table and sobbing. After a few moments she lifted her head and tried to calm herself in her sea of matchbooks, spread out on the table like stepping-stones to unseen worlds.

“Have you called his dad yet?”

“Are you speaking of Dave Jensen or Jay Freeman?”

Andes bit her lip. Apparently, the officer had been talking to people. What had they told him? Pick a father. Any father.

“Jay,” she said at last. Then, “How long am I going to be here?”

“That’s up to you.”

“How so?” The officer had another surprise waiting for her underneath the table, and he wasted no time producing it. It was extremely disorienting seeing his thick hand wrapped around her slim neck. It was her doll, Rose. Or what used to be her.

The left half of her body was completely charred; only one eye was still twinkly and blue, the other was seared out of its socket except for a single eyelash pointing straight up like the last stick standing in a desperate attempt to spell out “HELP” on a deserted beach. Gone was all but a few wisps of her silky blond hair, plastered against a blackened plastic head, and the remains of her purple dress were singed beyond repair. She was barely recognizable; Jane Doe, Jane Doll. Andes stared. The officer leaned in.

“Who did this, Emily?” he said. “Who’s been setting the fires?” Andes looked at her matches. She looked at the one-way mirror. She looked at the wall. She wanted to yell at him that he wasn’t supposed to call her Emily. Nobody had called her Emily for a long, long time. And okay, maybe she never legally changed her name, but a person should be called what they want to be called. Of course he couldn’t have known that. And even now she wasn’t opening her mouth to explain it to him. Because deep down, she was still Emily; she hadn’t run far enough or fast enough, she had always been Emily. The thought, while bringing tears to her eyes, brought with it a surprising sense of relief, of letting go. She thought about all the chances some people got in life, and then she thought about the kid out there and all that he’d already been through in his ten young years. Maybe it was too late for her, but she could still save him. “I used to be a peaceful world traveler,” Andes said. “Did you know that?”

“I asked the kid who’s been starting the fires. Do you want to know what he said?”

“Would you please go and cut that pizza in circles before it gets cold?”

“Why don’t you answer my question and then you can go and cut it yourself?”

“And remind him Gandhi was a lot older than ten, okay? But don’t say it like that—like he doesn’t already know exactly how old he was, because as you’ve probably figured out by now, the kid is a genius. And I’m not using that term lightly. But he does need emotional support.”

“What does Satya—oh what was he saying?”

“Satyagraha.”

“Yeah. Who’s that?”

“He’s trying to tell you he’s taking a nonviolent stand to my arrest. Ahimsa. You gotta love that kid. But you tell him he’s gotta eat. Just get a glass or a bowl or something and turn it upside down on the pizza and cut. But don’t make it an oval. He won’t eat an oval. Believe me, I learned that the hard way.” With that, Emily Tomlin leaned forward and snapped off the tape recorder.

“So what are you saying here?” the officer asked.

“I’d like to call that lawyer now,” Andes answered.

9 months earlier

Seattle, Washington

“Pedophile!” he screamed at her from the middle of the dock. “Pedophile!”

Andes Lane, a petite twenty-five-year-old world traveler, was standing on the dock with a worn green yoga mat clutched in one hand and a shiny penny outstretched in the other. In her split-second fantasy, the kid had taken the penny out of her hand and treated her to a dazzling smile, so in the moment, she was immobilized not only by the accusation hurled at her by the red-faced boy, but by the simple realization that no matter how Andes imagined people reacting, they always disappointed her.

And not only did the kid have a healthy set of lungs, but his declaration was buoyed by the water that surrounded them; Lake Union acted as a giant aqua echo chamber that amplified the boy’s voice, carrying his cry of “pedophile” out to every sailboat, house barge, and Fourth of July reveler on deck, as well as the boat full of Canadian tourists who were at that very moment passing by in Stanley’s Steamship, sipping on Stanley’s signature chocolate root beer floats and angling their digital cameras to get a better shot of the Sleepless in Seattle houseboat. When his cries of “pedophile” reached their finely tuned Canadian ears, they craned their necks to get a better look at her, the aforementioned pedophile, as they simultaneously praised and blamed the fall of the American dollar for the spectacle she had become. All that was missing was a bugle call and a posse of foxhounds unleashed for the hunt.

Instantly Andes’s mind conjured up horrible images: young, scraggly, long-haired convicts dangling puppies as they lured children into beat-up vans decorated with dancing bear bumper stickers, and middle-aged, potbellied perverts, palms stained with Skittles, sweet-talking innocent children into doing more than just sitting on Santa’s lap. She glanced down her body just to make sure she still had breasts, as the dock full of pale half-dressed Seattleites looked at her as if they were watching a live episode of To Catch A Predator.

Not that women couldn’t be pedophiles. In fact, she suddenly remembered it was in the Seattle area—Mary Kay someone—not the makeup lady, but the teacher who slept with her student and went on to have two children with him—shit—Letourneau—that was it, Mary Kay Letourneau, she remembered how sorry she felt for Mary Kay’s husband and her four children—although he’d since taken the kids to Alaska and remarried—all useless information at the moment—although fleeing to Alaska was starting to look like an attractive possibility. After all, she was fond of layering up and wouldn’t mind living in a place where at any given moment you could spot a moose or a bear ambling down the road.

Andes racked her brain for what she should say in her defense—I’m not a pedophile of course came to mind, but then she wondered if that would be like declaring you weren’t an alcoholic to your AA group. So instead she raised her yoga mat high above her head like an offering, as if a faithful practicer of Downward Facing Dog couldn’t possibly be expected to defend such drivel. My God. All she tried to do was give the boy the shiny penny she’d plucked off the dock—find a penny, pick it up, and all day long you’ll have good luck; a penny for your thoughts, and all that jazz. Would she be standing here humiliated if she had offered the kid a quarter instead? There was even a Sacagawea dollar in her fanny pack, but it was too late now.

If she were a pedophile, what would she say? She often played this mental game with directions, since she had no sense of them; if she reached a fork in the road, she would ask herself which way her instincts told her to go, and then she would go in the opposite direction, since her instincts usually led her astray. But if she were a pedophile, she would deny it, of course, so that was of little use in this situation. What Andes didn’t know as she stood there utterly humiliated was that she was about the tenth person the boy had called a pedophile that week, in part due to a recent school assembly on the subject, but mostly because the kid didn’t know how to scream at the person he was really angry with, the man who was currently bobbing in a rowboat underneath the dock. So instead, he unleashed his rage on strangers, giving him a shot of pleasure that often lasted the whole day.

Andes flipped the offending penny out onto Lake Union and held up the Houseboat for Rent advertisement she had torn off the bulletin board in the laundromat. “I’m looking for Jay,” she said. Suddenly, several people on the dock immediately looked at their feet. It struck her as odd, yet Andes couldn’t help but follow suit and look at her own feet. They were housed in bright pink flip-flops, and turning slightly pink, most likely because like her fingernails, her toenails were painted black, drawing the sun directly to them, roasting her little piggies one by one. She wiggled her toes and wondered if anyone would let her buy a hot dog or hamburger; it seemed as if every single sailboat was sporting a hibachi, and the smell of barbecue tugged at her hunger. She hadn’t eaten a single thing all day. It had been the last leg of her Greyhound trek from San Diego, and by the time the journey was done, she’d lost her appetite. But now that she was on land, even if by the sea, her hunger was returning with a vengeance. Just then one of the gatherers stomped on the dock.

“Jay,” the voice belonging to the stomping foot said. “You have company.” Seconds later, a pair of hands emerged from underneath the dock, gripped the wooden planks, and pulled. The tip of a rowboat slid out, and Andes found herself looking at a good-looking head in his early thirties. He had a strong, tanned face, sandy hair, and blue eyes that reminded her of a summer sky.

“Yes?” he asked, looking directly at Andes.

“Are you Jay?” she asked, jostling the advertisement.

“I am,” he answered. Then, before she could inquire about the houseboat, he said, “You don’t look like a pedophile to me.” Those who hadn’t ambled back to sunning themselves, or flipping burgers, or whatever else it was the residence of Westlake Marina did on the Fourth of July, laughed easily at the man’s joke. Andes did not. “Although I guess you never can tell these days,” Jay continued.

“I’m not a pedophile,” Andes said, but it was barely a whisper. Before she could explain or defend herself any further, a woman drowning in a flowered sundress, floppy orange hat, and oversized sunglasses descended on them. She was sloshing champagne from a crystal flute precariously balanced in her manicured hand. She tapped a long fingernail at the head in the rowboat.

“Jay,” she said. “I assume you got my message?” Jay pushed out a little farther, so that now he was a head, arms, and a chest. He crushed a can of Miller beer in his left fist and closed his eyes. “Jay?” the woman demanded. There was no reply. The woman turned and stared at Andes as if she were to blame. Even though his eyes were closed and he couldn’t possibly see her, Andes held the advertisement in Jay’s direction and jostled it up and down again.

“I was wondering if the houseboat was still for rent?”

“Be careful what you wish for, dear,” the woman said, pushing down on Andes’s forearm. She smelled like a field where a hundred gardenias had come to die. “Now, you listen to me, Jay. Did you or did you not get the message?”

“I did.”

“So we have an understanding?”

“We do.” Jay let the woman get a few steps away before continuing. “You left me a message, and I got it. That’s our understanding.” The woman stopped, turned on her red heels, and click-clacked back the few steps she had gained.

“I mean it, mister. If you urinate in my flowers again this year, I swear to God, I’ll—I’ll—”

“You’ll what?”

“I’ll call Child Protective Services!” the woman screamed. Andes first thought was: I didn’t know Child Protective Services handled plants. Her mind was already conjuring up overwrought social workers swarming in to protect verbally abused petunias. Then she followed the woman’s gaze down the dock in the direction of the kid. Andes let out a little gasp, but Jay just laughed.

“You promise, Mrs. Mueller?” he toyed. Mrs. Muller’s hand fluttered up to her sunglasses and she fiddled with them, even though they were perfectly snug around her face. A white line wrapped around her wedding finger, as if a well-worn ring had recently been removed. Jay must have been following her gaze, for he turned to Andes and said, “Do you know how many women chuck their engagement and wedding rings into this lake?”

An old man sitting on the deck of a yacht behind them shot up and shouted, “Betty!”

“If you take Stanley’s tour along the lake, he’ll tell you all about the heartbroken brides-to-be and brides who have tossed their tiny little diamonds into the lake. Now, men would never be that stupid, even if the thing is tiny. We’d pawn it.” Andes was trying politely to listen to the story, but it was rather difficult given the fact that she’d never actually seen another human being vibrate without the help of any electronics. But Betty Mueller’s body was literally shaking.

“I mean it, Jay. Any drunk and disorderly behavior out of you today and I’m calling the police.”

“Betty,” the old man shouted again. “You said you lost that ring!” Mrs. Mueller click-clacked away again, even ignoring the old man in the yacht, leaving Andes to wonder who was talking to whom. Jay looked up at Andes and smiled.

“Now, if I pee in the kid’s Kool-Aid, I can see calling CPS. Or his science project. He made a volcano last year. Come to think of it, pissing on it would have been brilliant! It would have given it the extra spurt it needed. Thing didn’t explode whatsoever. Just kind of gurgled and then popped.” Andes held up the flier again, for she had nothing to say on the subject of pissing or premature-ejaculating volcanoes, and her fair skin was at the mercy of the sun.

“I want to rent this houseboat,” she said.

“Finally,” he said. “I’ve put up dozens of those fliers, and had just about given up.”

Dozens? Andes tried to feign surprise, but the reality was she’d spent the entire morning taking down every one of them within a three-mile radius so nobody else could beat her to it. Now, standing on the dock, looking out toward the lake, she spotted several houseboats, shoebox-shaped barges gently bobbing in the water. She prayed the blue one in the middle was the one for rent.

“So it’s still available?” Andes asked.

“It will be,” Jay said. “After tonight, of course.”

“Oh.” As Andes wondered where she would spend the night, Jay pushed off with his hands, sending the entire rowboat into view. Instead of pulling himself up onto the dock, he simply floated in front of her and studied her. Full six-packs of Miller Lite rested on either side of him, and empty cans formed little mountains at his feet. Andes took a moment to gaze out onto the lake. It was a perfect July day. Lake Union looked custom-made for the celebration, glittering like a giant sparkler, bouncing pins of light off the water and shooting them into to the sky.

Andes’s eyes feasted on the houseboats once again. She’d already fallen in love; it had to be the little blue one in the middle. She stood on the dock, not knowing whether she was coming or going, her body stiff and still, as if she were waiting for a gust of wind to come along and make up her mind. Up ahead the kid was kneeling on the dock, his shoulders hunched over to such a degree that the tip of his runny nose was practically kissing the lake, his lips almost brushing against the discarded debris the lake had gathered into its core. It was standing here taking in his collapsed frame that Andes felt a surge of pity for the boy, and something akin to a motherly instinct grabbed her so hard she swayed on the dock and had to do a little two-step to keep from keeling over.

“Easy there,” Jay said. “And here I was going to offer you a beer.” At this the kid’s head shot up, although how he could have possibly heard that all the way down the dock, she didn’t know, but suddenly he was glaring at her, and she half expected him to scream obscenities at her again, only this time instead of hating him, she felt tender toward the boy. But he didn’t scream at her, he simply lasered her with a lifetime of hatred and then stomped out of sight. Without turning his head in that direction, Jay shrugged an apology.

“He’s been a little bastard lately,” he said. Andes didn’t return the smile Jay offered; whereas moments ago she’d hated the kid, now she didn’t want to be complicit in putting him down.

“Is he your son?” she asked.

“Guess that would make me the big bastard, huh?” Jay joked. “I’m Big Bastard Senior, he’s Little Bastard Junior.” Andes didn’t laugh. She found whenever she laughed at men’s jokes, they fell instantly in love with her. She did have a magical laugh, and those in the presence of it often yearned for more. But she was turning over a new leaf, looking for a home, a place to settle down. She needed the attention of a sarcastic boozer like she needed another hole in her thong.

“Are you sprouting roots?” Jay asked, hauling himself onto the dock.

“What?”

“Let’s move. I’ll show you Luna.”

“Luna?”

“The house barge. That’s what we call her.” Andes fell in step behind Jay, wondering as she watched him walk if he always swaggered like that, or if it was because of the slight movement of the dock, or was it the beer? After all, he was putting the beers away pretty fast, but it was a holiday, America’s birthday, as good a time to get sauced before noon as any, she guessed. She wasn’t a big drinker herself. She did like an occasional glass of spirits, but something of her upbringing must have stuck with her, for she never wanted to imbibe to the point where she lost control and thus increased her chances of committing a mortal sin. God was her parents’ drug of choice, and as it turned out quite an unforgiving one at that.

But everyone on the dock was drinking or halfway to drunk, so why was she being so judgmental? Jay probably didn’t drink much at all, which was why he was going a little overboard today, everything in moderation, and that probably included overdoing it.

As they drew closer to the houseboats, Andes’s excitement grew. This was a dream come true. She thought of all the crappy apartments she’d been living in the last nine years, ever since she left home at the age of sixteen. This was it, this was finally her “making it,” this was going to be home. It was a choice, she realized. Not something you stumbled upon, or found, or forced. It was simply a choice to land somewhere and say. This is where I’m going to stay. No matter what, this is where I’m going to make the best of things. Kind of like a marriage. She’d been waiting too long to find a place where she felt like she belonged; it was time to just settle. Make it so.

Jay stopped short of the house barges, and climbed into a twenty-four-foot sailboat docked at the end of the dock. The houseboat was off to the left, they should be turning left. Then it hit her. It wasn’t one of those cute little houseboats he was trying to rent out, it was this sailboat. She’d fallen for the old bait-and-switch. Sure, as sailboats went, it was something. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...