- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

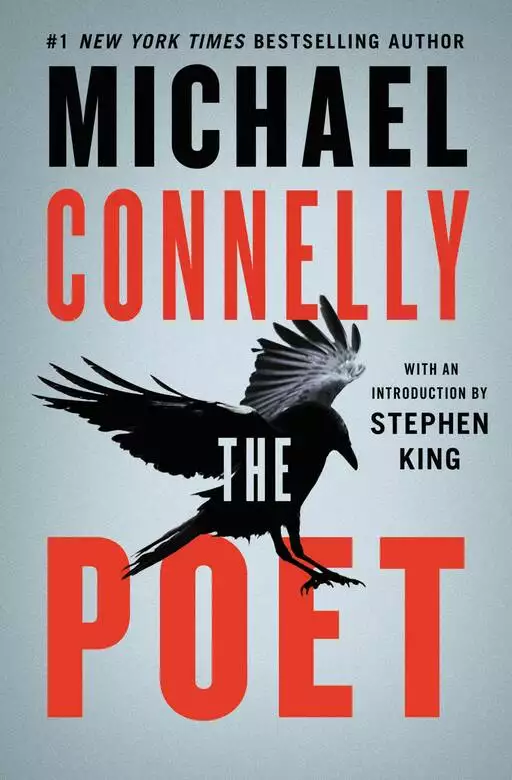

With his four Harry Bosch novels, Michael Connelly joined 'the top rank of a new generation of crime writers' (Los Angeles Times). Now Connelly returns with his most searing thriller yet—a major new departure that recalls the best work of Thomas Harris (Red Dragon, Silence of the Lambs) and James Patterson (Along Came a Spider).

Our hero is Jack McEvoy, a Rocky Mountain News crime-beat reporter. As the novel opens, Jack's twin brother, a Denver homicide detective, has just killed himself. Or so it seems. But when Jack begins to investigate the phenomenon of police suicides, a disturbing pattern emerges, and soon suspects that a serial murderer is at work—a devious cop killer who's left a coast-to-coast trail of 'suicide notes' drawn from the poems of Edgar Allan Poe. It's the story of a lifetime—except that 'the Poet' already seems to know that Jack is trailing him.…

Here is definitive proof that Michael Connelly is among the best suspense novelist working today.

Release date: April 29, 2003

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Poet

Michael Connelly

forge my professional reputation on it. I treat

it with the passion and precision of an undertaker—somber and sympathetic about it when I’m with the

bereaved, a skilled craftsman with it when I’m alone. I’ve

always thought the secret of dealing with death was to

keep it at arm’s length. That’s the rule. Don’t let it breathe

in your face.

But my rule didn’t protect me. When the two detectives

came for me and told me about Sean, a cold numbness

quickly enveloped me. It was like I was on the other side

of the aquarium window. I moved as if underwater—back

and forth, back and forth—and looked out at the rest of the

world through the glass. From the backseat of their car I

could see my eyes in the rearview mirror, flashing each

time we passed beneath a streetlight. I recognized the thousand-yard stare I had seen in the eyes of fresh widows I had

interviewed over the years.

I knew only one of the two detectives. Harold Wexler. I

had met him a few months earlier when I stopped into the

Pints Of for a drink with Sean. They worked CAPs together

on the Denver PD. I remember Sean called him Wex. Cops

always use nicknames for each other. Wexler’s is Wex,

Sean’s, Mac. It’s some kind of tribal bonding thing. Some of

the names aren’t complimentary but the cops don’t complain. I know one down in Colorado Springs named Scoto

whom most other cops call Scroto. Some even go all the

way and call him Scrotum, but my guess is that you have

to be a close friend to get away with that.

Wexler was built like a small bull, powerful but squat. A

voice slowly cured over the years by cigarette smoke and

whiskey. A hatchet face that always seemed red the times I

saw him. I remember he drank Jim Beam over ice. I’m always interested in what cops drink. It tells a lot about

them. When they’re taking it straight like that, I always

think that maybe they’ve seen too many things too many

times that most people never see even once. Sean was

drinking Lite beer that night, but he was young. Even

though he was the supe of the CAPs unit, he was at least

ten years younger than Wexler. Maybe in ten years he

would have been taking his medicine cold and straight like

Wexler. But now I’ll never know.

I spent most of the drive out from Denver thinking

about that night at the Pints Of. Not that anything important had happened. It was just drinks with my brother at

the cop bar. And it was the last good time between us, before Theresa Lofton came up. That memory put me back in

the aquarium.

But during the moments that reality was able to punch

through the glass and into my heart, I was seized by a

feeling of failure and grief. It was the first real tearing of the

soul I had experienced in my thirty-four years. That included the death of my sister. I was too young then to

properly grieve for Sarah or even to understand the pain of

a life unfulfilled. I grieved now because I had not even

known Sean was so close to the edge. He was Lite beer

while all the other cops I knew were whiskey on the rocks.

Of course, I also recognized how self-pitying this kind of

grief was. The truth was that for a long time we hadn’t listened much to each other. We had taken different paths.

And each time I acknowledged this truth the cycle of my

grief would begin again.

My brother once told me the theory of the limit. He said

every homicide cop had a limit but the limit was unknown

until it was reached. He was talking about dead bodies.

Sean believed that there were just so many that a cop could

look at. It was a different number for every person. Some

hit it early. Some put in twenty in homicide and never got

close. But there was a number. And when it came up, that

was it. You transferred to records, you turned in your

badge, you did something. Because you just couldn’t look

at another one. And if you did, if you exceeded your limit,

well, then you were in trouble. You might end up sucking

down a bullet. That’s what Sean said.

I realized that the other one, Ray St. Louis, had said something to me.

He turned around in his seat to look back at me. He was

much larger than Wexler. Even in the dim light of the car

I could make out the rough texture of his pockmarked

face. I didn’t know him but I’d heard him referred to by

other cops and I knew they called him Big Dog. I had

thought that he and Wexler made the perfect Mutt and Jeff

team when I first saw them waiting for me in the lobby at

the Rocky. It was like they had stepped out of a late-night

movie. Long, dark overcoats, hats. The whole scene should

have been in black and white.

“You hear me, Jack. We’ll break it to her. That’s our job,

but we’d just like you to be there to sort of help us out,

maybe stay with her if it gets rough. You know, if she needs

to be with somebody. Okay?”

“Okay.”

“Good, Jack.”

We were going to Sean’s house. Not the apartment he

split with four other cops in Denver so in accordance with

city regs he was a Denver resident. His house in Boulder

where his wife, Riley, would answer our knock. I knew nobody was going to be breaking anything to her. She’d know

what the news was the moment she opened the door and

saw the three of us standing there without Sean. Any cop’s

wife would know. They spend their lives dreading and

preparing for that day. Every time there’s a knock on the

door they expect it to be death’s messengers standing there

when they open it. This time it would be.

“You know, she’s going to know,” I told them.

“Probably,” Wexler said. “They always do.”

I realized they were counting on Riley knowing the

score as soon as she opened the door. It would make their

job easier.

I dropped my chin to my chest and brought my fingers

up beneath my glasses to pinch the bridge of my nose. I realized I had become a character in one of my own stories—exhibiting the details of grief and loss I worked so hard to

get so I could make a thirty-inch newspaper story seem

meaningful. Now I was one of the details in this story.

A sense of shame descended on me as I thought of all the

calls I had made to a widow or parent of a dead child. Or

brother of a suicide. Yes, I had even made those. I don’t

think there was any kind of death that I hadn’t written

about, that hadn’t brought me around as the intruder into

somebody’s pain.

How do you feel? Trusty words for a reporter. Always the

first question. If not so direct, then carefully camouflaged

in words meant to impart sympathy and understanding—feelings I didn’t actually have. I carried a reminder of this

callousness. A thin white scar running along my left cheek

just above the line of my beard. It was from the diamond

engagement ring of a woman whose fiancé had been killed

in an avalanche near Breckenridge. I asked her the old

standby and she responded with a backhand across my

face. At the time I was new to the job and thought I had

been wronged. Now I wear the scar like a badge.

“You better pull over,” I said. “I’m going to be sick.”

Wexler jerked the car into the freeway’s breakdown lane.

We skidded a little on the black ice but then he got control.

Before the car had completely stopped I tried desperately

to open the door but the handle wouldn’t work. It was a detective car, I realized, and the passengers who most often

rode in the back were suspects and prisoners. The back

doors had security locks controlled from the front.

“The door,” I managed to strangle out.

The car finally jerked to a stop as Wexler disengaged the

security lock. I opened the door, leaned out and vomited

into the dirty slush. Three great heaves from the gut. For a

half a minute I didn’t move, waiting for more, but that was

it. I was empty. I thought about the backseat of the car. For

prisoners and suspects. And I guessed that I was both now.

Suspect as a brother. A prisoner of my own pride. The sentence, of course, would now be life.

Those thoughts quickly slipped away with the relief the

physical exorcism brought. I gingerly stepped out of the

car and walked to the edge of the asphalt where the light

from the passing cars reflected in moving rainbows on the

petroleum-exhaust glaze on the February snow. It looked

as if we had stopped alongside a grazing meadow but I

didn’t know where. I hadn’t been paying attention to how

far along to Boulder we were. I took off my gloves and

glasses and put them in the pockets of my coat. Then I

reached down and dug beneath the spoiled surface to

where the snow was white and pure. I took up two handfuls of the cold, clean powder and pressed it to my face,

rubbing my skin until it stung.

“You okay?” St. Louis asked.

He had come up behind me with his stupid question. It

was up there with How do you feel? I ignored it.

“Let’s go,” I said.

We got back in and Wexler wordlessly pulled the car

back onto the freeway. I saw a sign for the Broomfield exit

and knew we were about halfway there. Growing up in

Boulder, I had made the thirty-mile run between there and

Denver a thousand times but the stretch seemed like alien

territory to me now.

For the first time I thought of my parents and how they

would deal with this. Stoicly, I decided. They handled

everything that way. They never discussed it. They moved

on. They’d done it with Sarah. Now they’d do it with Sean.

“Why’d he do it?” I asked after a few minutes.

Wexler and St. Louis said nothing.

“I’m his brother. We’re twins, for Christ’s sake.”

“You’re also a reporter,” St. Louis said. “We picked you

up because we want Riley to be with family if she needs it.

You’re the only—”

“My brother fucking killed himself!”

I said it too loud. It had a quality of hysteria to it that I

knew never worked with cops. You start yelling and they

have a way of shutting down, going cold. I continued in a

subdued voice.

“I think I am entitled to know what happened and why.

I’m not writing a fucking story. Jesus, you guys are…”

I shook my head and didn’t finish. If I tried I thought I

would lose it again. I gazed out the window and could see

the lights of Boulder coming up. So many more than when

I was a kid.

“We don’t know why,” Wexler finally said after a half

minute. “Okay? All I can say is that it happens. Sometimes

cops get tired of all the shit that comes down the pipe. Mac

might’ve gotten tired, that’s all. Who knows? But they’re

working on it. And when they know, I’ll know. And I’ll tell

you. That’s a promise.”

“Who’s working on it?”

“The park service turned it over to our department. SIU

is handling it.”

“What do you mean Special Investigations? They don’t

handle cop suicides.”

“Normally, they don’t. We do. CAPs. But this time it’s

just that they’re not going to let us investigate our own.

Conflict of interest, you know.”

CAPs, I thought. Crimes Against Persons. Homicide, assault, rape, suicide. I wondered who would be listed in the

reports as the person against whom this crime had been

committed. Riley? Me? My parents? My brother?

“It was because of Theresa Lofton, wasn’t it?” I asked,

though it wasn’t really a question. I didn’t feel I needed

their confirmation or denial. I was just saying out loud

what I believed to be the obvious.

“We don’t know, Jack,” St. Louis said. “Let’s leave it at

that for now.”

The death of Theresa Lofton was the kind of murder that

gave people pause. Not just in Denver, but everywhere. It

made anybody who heard or read about it stop for at least

a moment to consider the violent images it conjured in the

mind, the twist it caused in the gut.

Most homicides are little murders. That’s what we call

them in the newspaper business. Their effect on others is

limited, their grasp on the imagination is short-lived. They

get a few paragraphs on the inside pages. Buried in the

paper the way the victims are buried in the ground.

But when an attractive college student is found in two

pieces in a theretofore peaceful place like Washington

Park, there usually isn’t enough space in the paper for all

the inches of copy it will generate. Theresa Lofton’s was no

little murder. It was a magnet that pulled at reporters from

across the country. Theresa Lofton was the girl in two

pieces. That was the catchy thing about this one. And so

they descended on Denver from places like New York and

Chicago and Los Angeles, television, tabloid and newspaper reporters alike. For a week, they stayed at hotels with

good room service, roamed the city and the University of

Denver campus, asked meaningless questions and got

meaningless answers. Some staked out the day care center

where Lofton had worked part-time or went up to Butte,

where she had come from. Wherever they went they

learned the same thing, that Theresa Lofton fit that most

exclusive media image of all, the All-American Girl.

The Theresa Lofton murder was inevitably compared to

the Black Dahlia case of fifty years ago in Los Angeles. In

that case, a not so All-American Girl was found severed at

the midriff in an empty lot. A tabloid television show

dubbed Theresa Lofton the White Dahlia, playing on the

fact that she had been found on a snow-covered field near

Denver’s Lake Grassmere.

And so the story fed on itself. It burned as hot as a trash-can fire for almost two weeks. But nobody was arrested and

there were other crimes, other fires for the national media

to warm itself by. Updates on the Lofton case dropped back

into the inside pages of the Colorado papers. They became

briefs for the digest pages. And Theresa Lofton finally took

her spot among the little murders. She was buried.

All the while, the police in general, and my brother in

particular, remained virtually mute, refusing even to confirm the detail that the victim had been found in two parts.

That report had come only by accident from a photographer at the Rocky named Iggy Gomez. He had been in the

park looking for wild art—the feature photos that fill

the pages on a slow news day—when he happened upon the

crime scene ahead of any other reporters or photographers.

The cops had made the callouts to the coroner’s and crime

scene offices by landline since they knew the Rocky and the

Post monitored their radio frequencies. Gomez took shots

of two stretchers being used to remove two body bags. He

called the city desk and said the cops were working a two-bagger and from the looks of the size of the bags the victims were probably children.

Later, a cop shop reporter for the Rocky named Van Jackson got a source in the coroner’s office to confirm the grim

fact that a victim had come into the morgue in two parts.

The next morning’s story in the Rocky served as the siren

call to the media across the country.

My brother and his CAPs team worked as if they felt no

obligation to talk to the public at all. Each day, the Denver

Police Department media office put out a scant few lines in

a press release, announcing that the investigation was continuing and that there had been no arrests. When cornered,

the brass vowed that the case would not be investigated in

the media, though that in itself was a laughable statement.

Left with little information from authorities, the media did

what it always does in such cases. It investigated the case

on its own, numbing the reading and television-watching

public with assorted details about the victim’s life that actually had nothing to do with anything.

Still, almost nothing leaked from the department and little was known outside headquarters on Delaware Street;

and after a couple of weeks the media onslaught was over,

strangled by the lack of its lifeblood, information.

I didn’t write about Theresa Lofton. But I wanted to. It

wasn’t the kind of story that comes along often in this place

and any reporter would have wanted a piece of it. But at

first, Van Jackson worked it with Laura Fitzgibbons, the

university beat reporter. I had to bide my time. I knew that

as long as the cops didn’t clear it, I’d get my shot at it. So

when Jackson asked me in the early days of the case if I

could get anything from my brother, even off the record, I

told him I would try, but I didn’t try. I wanted the story and

I wasn’t going to help Jackson stay on it by feeding him

from my source.

In late January, when the case was a month old and had

dropped out of the news, I made my move. And my mistake.

One morning I went in to see Greg Glenn, the city editor, and told him I’d like to do a take out on the Lofton

case. That was my specialty, my beat. Long takes on the notable murders of the Rocky Mountain Empire. To use a

newspaper cliché, my expertise was going behind the

headlines to bring you the real story. So I went to Glenn

and reminded him I had an in. It was my brother’s case, I

said, and he’d only talk to me about it. Glenn didn’t hesitate to consider the time and effort Jackson had already put

on the story. I knew that he wouldn’t. All he cared about

was getting a story the Post didn’t have. I walked out of the

office with the assignment.

My mistake was that I told Glenn I had the in before I

had talked to my brother. The next day I walked the two

blocks from the Rocky to the cop shop and met him for

lunch in the cafeteria. I told him about my assignment.

Sean told me to turn around.

“Go back, Jack. I can’t help you.”

“What are you talking about? It’s your case.”

“It’s my case but I’m not cooperating with you or

anybody else who wants to write about it. I’ve given the basic

details, that’s all I’m required to do, that’s where it stays.”

He looked off across the cafeteria. He had an annoying

habit of not looking at you when you disagreed with him.

When we were little, I would jump on him when he did it

and punch him on the back. I couldn’t do that anymore,

though many times I wanted to.

“Sean, this is a good story. You have—”

“I don’t have to do anything and I don’t give a shit what

kind of story it is. This one is bad, Jack. Okay? I can’t stop

thinking about it. And I’m not going to help you sell newspapers with it.”

“C’mon, man, I’m a writer. Look at me. I don’t care if it

sells papers or not. The story is the thing. I don’t give a shit

about the paper. You know how I feel about that.”

He finally turned back to me.

“Now you know how I feel about this case,” he said.

I was silent a moment and took out a cigarette. I was

down to maybe half a pack a day back then and could have

skipped it but I knew it bothered him. So I smoked when

I wanted to work on him.

“This isn’t a smoking section, Jack.”

“Then turn me in. At least you’ll be arresting somebody.”

“Why are you such an asshole when you don’t get what

you want?”

“Why are you? You aren’t going to clear it, are you?

That’s what this is all about. You don’t want me digging

around and writing about your failure. You’re giving up.”

“Jack, don’t try the below-the-belt shit. You know it’s

never worked.”

He was right. It never had.

“Then what? You just want to keep this little horror

story for yourself? That it?”

“Yeah, something like that. You could say that.”

In the car with Wexler and St. Louis I sat with my arms

crossed. It was comforting. Almost as if I were holding myself together. The more I thought about my brother the

more the whole thing made no sense to me. I knew the

Lofton case had weighed on him but not to the point that

he’d want to take his own life. Not Sean.

“Did he use his gun?”

Wexler looked at me in the mirror. Studied me, I

thought. I wondered if he knew what had come between

my brother and me.

“Yes.”

It hit me then. I just didn’t see it. All the times that we’d

had together coming to that. I didn’t care about the Lofton

case. What they were saying couldn’t be.

“Not Sean.”

St. Louis turned around to look at me.

“What’s that?”

“He wouldn’t have done it, that’s all.”

“Look, Jack, he—”

“He didn’t get tired of the shit coming down the pipe. He

loved it. You ask Riley. You ask anybody on the—Wex, you

knew him the best and you know it’s bullshit. He loved the

hunt. That’s what he called it. He wouldn’t have traded it

for anything. He probably could have been the assistant

fucking chief by now but he didn’t want it. He wanted to

work homicides. He stayed in CAPs.”

Wexler didn’t reply. We were in Boulder now, on

Baseline heading toward Cascade. I was falling through the silence of the car. The impact of what they were telling me

Sean had done was settling on me and leaving me as cold

and dirty as the snow back on the side of the freeway.

“What about a note or something?” I said. “What—”

“There was a note. We think it was a note.”

I noticed St. Louis glance over at Wexler and give him a

look that said, you’re saying too much.

“What? What did it say?”

There was a long silence, then Wexler ignored St. Louis.

“Out of space,” he said. “Out of time.”

“ ‘Out of space. Out of time.’ Just like that?”

“Just like that. That’s all it said.”

The smile on Riley’s face lasted maybe three seconds. Then

it was instantly replaced by a look of horror out of that

painting by Munch. The brain is an amazing computer.

Three seconds to look at three faces at your door and to

know your husband isn’t coming home. IBM could never

match that. Her mouth formed into a horrible black hole

from which an unintelligible sound came, then the inevitable useless word: “No!”

“Riley,” Wexler tried. “Let’s sit down a minute.”

“No, oh God, no!”

“Riley…”

She retreated from the door, moving like a cornered animal, first darting one way and then the opposite, as if

maybe she thought she could change things if she could

elude us. She went around the corner into the living room.

When we followed we found her collapsed on the middle

of the couch in an almost catatonic state, not too

dissimilar from my own. The tears were just starting to come to

her eyes. Wexler sat next to her on the couch. Big Dog and

I stood by, silent as cowards.

“Is he dead?” she asked, knowing the answer but realizing she had to get it over with.

Wexler nodded.

“How?”

Wexler looked down and hesitated a moment. He

looked over at me and then back at Riley.

“He did it himself, Riley. I’m sorry.”

She didn’t believe it, just as I hadn’t. But Wexler had a way

of telling the story and after a while she stopped protesting.

That was when she looked at me for the first time, tears

rolling. Her face had an imploring look, as if she were asking me if we were sharing the same nightmare and couldn’t

I do something about it. Couldn’t I wake her up? Couldn’t

I tell these two characters from a black and white how

wrong they were? I went to the couch, sat next to her and

hugged her. That’s what I was there for. I’d seen this scene

often enough to know what I was supposed to do.

“I’ll stay,” I whispered. “As long as you like.”

She didn’t answer. She turned from my arms to Wexler.

“Where did it happen?”

“Estes Park. By the lake.”

“No, he wouldn’t go—what was he doing up there?”

“He got a call. Somebody said they might have some information about one of his cases. He was going up to meet

them for coffee at the Stanley. Then after he… he drove

out to the lake. We don’t know why he went there. He was

found in his car by a ranger who heard the shot.”

“What case?” I asked.

“Look, Jack, I don’t want to get into—”

“What case?” I yelled, this time not caring about the inflection of my voice. “It was Lofton, wasn’t it?”

Wexler gave one short nod and St. Louis walked away

shaking his head.

“Who was he meeting?”

“That’s it, Jack. We’re not going to get into that with

you.”

“I’m his brother. This is his wife.”

“It’s all under investigation but if you’re looking for

doubts, there aren’t any. We were up there. He killed himself. He used his own gun, he left a note and we got GSR

on his hands. I wish he didn’t do it. But he did.”

In the winter in Colorado the earth comes out

in frozen chunks when they dig through the

frost line with the backhoe to open up a grave.

My brother was buried in Green Mountain Memorial Park

in Boulder, a spot not more than a mile from the house

where we grew up. As kids we were driven by the cemetery

on our way to summer camp hikes in Chautauqua Park. I

don’t think we ever once looked at the stones as we passed

and thought of the confines of the cemetery as our own

final destination, but now that was what it was to be for

Sean.

Green Mountain stood over the cemetery like a huge

altar, making the small gathering at his grave seem even

smaller. Riley, of course, was there, along with her parents

and mine, Wexler and St. Louis, a couple dozen or so other

cops, a few high school friends that neither Sean nor I nor

Riley had stayed in touch with and me. It wasn’t the official

police burial, with all the fanfare and colors. That ritual

was reserved for those who fell in the line of duty. Though

it could be argued that it was still a line-of-duty death, it

wasn’t considered one by the department. So Sean didn’t

get the Show and most of the Denver police force stayed

away. Suicide is believed to be contagious by many in the

thin blue line.

I was one of the pallbearers. I took the front along with

my father. Two cops I didn’t know before that day, but who

were on Sean’s CAPs team, took the middle, and Wexler

and St. Louis were on the back. St. Louis was too tall and

Wexler too short. Mutt and Jeff. It gave the coffin an uneven cant at the back as we carried it. I think it must have

looked odd. My mind wandered as we struggled with the

weight and I thought of Sean’s body pitching around inside

it.

I didn’t say much to my parents that day, though I rode

with them in the limousine with Riley and her parents. We

had not talked of anything meaningful in many years and

even Sean’s death could not penetrate the barrier. After my

sister’s death twenty years before, something in them

changed toward me. It seemed that I, as the survivor of the

accident, was suspect for having done just that. Survived. I

am also sure that since that time I have continued to disappoint them in the choices I have made. I think of these

as small disappointments accruing over time like interest

in a bank account until it was enough for them to comfortably retire on. We are strangers. I see them only on the

required holidays. And so there was nothing that I could

say to them that would matter and there was nothing they

could say to me. Aside from the occasional hurt-animal

sound of Riley crying, the inside of the limo was as quiet

as the inside of Sean’s casket.

After the funeral I took two weeks of vacation and the one

week of bereavement leave the paper allowed and drove by

myself up into the Rockies. The mountains have never lost

their glory for me. It’s mountains where I heal the fastest.

Headed west on the 70, I drove through the Loveland

Pass and over the peaks to Grand Junction. I did it slowly,

taking three days. I stopped to ski; sometimes I just

stopped on the turnouts to think. After Grand Junction I

diverted south and made it to Telluride the next day. I kept

the Cherokee in four-wheel drive the whole way. I stayed

in Silverton because the rooms were cheaper and skied

every day for a week. I spent the nights drinking Jagermeister in my room or near the fireplace of whatever ski

lodge I stopped in. I tried to exhaust my body with the

hope that my mind would follow. But I couldn’t succeed. It

was all Sean. Out of space. Out of time. His last message

was a riddle my mind could not put aside.

For some reason my brother’s noble calling had betrayed

him. It had killed him. The grief that this simple conclusion brought me would not ebb, even when I was gliding

down the slopes, the wind cutting in behind my sunglasses

and pulling tears from my eyes.

I no longer questioned the official conclusion but it had

not been Wexler and St. Louis who had convinced me. I

did that on my own. It was the erosion of my resolve by

time and by facts. As each day went by, the horror of what

he had done was somehow easier to believe and even accept. And then there was Riley. On the day after that first

night she had told me something that even Wexler and St.

Louis hadn’t known yet. Sean had been going once a week

to see a psychologist. Of course, there were counseling services available to him through the department, but he had

chosen this secret path because he didn’t want his position

to be undermined by rumors.

I came to realize he was seeing the therapist at the same

time I went to him wanting to write about Lofton. I

thought maybe he was trying to spare me the same anguish

that the case had brought him. I liked the thought that that

was what he was doing and I tried to hold on to that idea

during those days up in the mountains.

In front of the hotel room mirror one night after too

many drinks, I contemplated shaving my beard off and cutting my hair short like Sean’s had been. We were identical

twins—same hazel eyes, light brown hair, lanky build—but not many people realized that. We had always gone to

great lengths to forge separate identities. Se

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...