- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

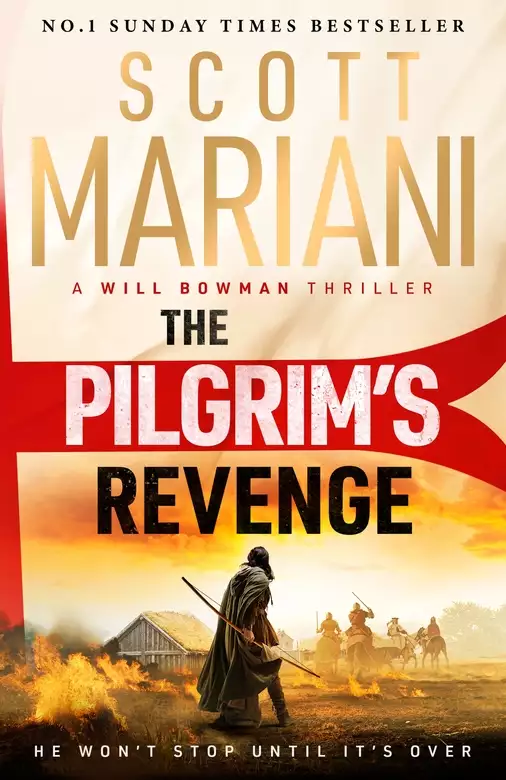

THE NEW THRILLER FROM THE NUMBER ONE BESTSELLER

1190 - Humble layman Will Bowman lives in the countryside with his pregnant wife, when soldiers from Richard Lionheart's army tear through his home. Will is beaten unconscious, and awakes to find his wife murdered, his farm burnt down, and his life forever changed.

In vengeance, Will infiltrates Richard's army to find the marauding gang, and finds himself swept along in the march of the Crusades. With the help of new allies and fuelled by his loss, Will crosses Europe with the King's army.

Can Will avenge his wife? Or will he be swept away by the unstoppable force of Richard's Crusade?

Release date: June 5, 2025

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Pilgrim's Revenge

Scott Mariani

It was a fine morning soon before Easter in the year of our Lord 1190, and the early spring sunshine shone down upon the quiet rural community of Foxwood.

The somewhat disorderly and rambling arrangement of thatched wattle-and-daub dwellings on their narrow little streets, the tiny church, the smithy, the old watermill and sundry other buildings, barns, pens and stables, and of course the grand house belonging to the lord of the manor, stood nestled in a pleasant green valley on the southerly banks of the River Windrush. Home to three hundred and eighty-seven souls at the last count, the village and surrounding farmland occupied some thousand or so acres at the heart of the county of Oxfordshire, though for the majority of the villagers who spent their days working the land, crafting their wares and minding their livestock, the great city of Oxford was so remote as to belong to a different world – to say nothing of faraway London.

Life continued here in much the same fashion as it had for countless generations, largely untouched by whatever went on beyond the boundaries of the manor estate. The neighbouring hamlet of Clanfield lay an hour’s leisurely ride to the south, while the slightly larger town of Wexby stood some way further west. Midway between there and the village, the other side of the half-forested mound of Foxwood Hill and across the river, was the ancient greystone Benedictine monastery and convent of Wexby Abbey, housing some two dozen nuns and a few monks who pursued their unobtrusive, contemplative existence under the auspices of the formidable but kindly Mother Matilda.

And it was towards Wexby Abbey that a solitary cart could be seen travelling at this moment, pulled by an old grey mare and plodding its unhurried way westwards along the narrow road. The tall grass verges that rolled by on either side were bursting into colour with the first springtime wildflowers, bluebells and primroses and cow parsley; a family of swans gently glided along the course of the meandering river that sparkled in the sunshine. The dirt road was often impassably muddy during the wintertime, but the coming warmer months would soon bake the ruts as hard as fired clay.

The swaying, creaking cart was laden with fresh firewood, split logs of oak, beech and ash and bundles of cut sticks for kindling, along with other supplies that its lone driver was transporting for delivery to the abbey. He was a young man, christened William though everybody called him Will, and simply dressed in the loose-fitting attire of a countryman.

The village of Foxwood and its surrounds were the only home young Will had ever known, and never in the course of his score of years had he ventured more than a few miles in any given direction. He was as familiar with every individual villager as with every inch of the village itself, and for him it was a place synonymous with peace, harmony and a kind of inner contentment that buoyed his spirit, especially at this happy time of his life. He loved Foxwood’s traditions and unchanging routines, the clutter and industry of its narrow streets, its smells of woodsmoke and hay and freshly baked bread in the mornings, the sounds: the crying of babies; the squeal of hogs being butchered; the clatter of cartwheels; the ringing of the church bell; the metallic clang-clang of the smithy; the barking of dogs and the honking of geese; the grind and splash of the miller’s waterwheel; and the thwack of the flail come threshing time. All of it was dear to his heart: the good, the gritty and the plain disreputable, like the bloody bare-knuckle brawls that now and then broke out in the alley behind the alehouse, and the things that were known to go on in the upstairs room of that abode at the end of Main Street.

Though he firmly considered himself one of the people of Foxwood, Will had been born and always lived outside of it, on a small humble homestead half a mile from its outskirts and on the edge of the forest. His life also differed markedly from those of many of his fellow villagers in that, unlike the peasant labourers who tended to the lord’s fields and were for all practical purposes his property, he was neither a serf nor a cottager and served no direct master other than God Almighty Himself – except perhaps the king, who seemed to him such an obscure and nebulous figure that he might as well not have existed in real life. No; Will was instead that rarest of things among the common people of the world he inhabited, a free man: free to marry as he pleased, to make whatever use he wished of his modest landholding, and to pursue his own living unshackled to the demands of the manor that dominated the existence of the majority of its population.

He knew only too well how blessed he was by good fortune, even though in his own way he worked just as hard as any of those who were tied to their duty of labouring in their lord’s fields. It was by no means a life of comfort but a privileged one nonetheless, come down to him from his father who had earned these advantages for his family by his own blood and sweat. Will’s mother had died when her only child was still just a small boy, and he had been raised by his father until he, too, passed away when Will was around fifteen years of age. The inheritance left to his son consisted of a half virgate of pasture and woods – some fourteen acres that included a stretch along the river, on which Will kept a small rowing boat for going fishing.

It was now eighteen months since Will had married Beatrice, the lovely, lively golden-haired miller’s daughter with whom he’d been besotted and had admired from afar since they were both little more than children, never daring to speak to her until the day he’d discovered, to his amazement and joy, that she had also had a fond eye for him. The home the young couple shared was a simple timber-framed house furnished with a trestle table, a wooden bench, a straw bed in one corner and a rudimentary kitchen area in another, equipped with a few iron pots, a little pottery ware and wooden spoons used for cooking and eating. In the adjoining byre lived their four pigs, a dozen chickens, two goats and a sour-tempered cat called Gyb, who kept the vermin down and came and went as he pleased. Next door was a larger outbuilding that served as a stable for the grey mare and Will’s pair of plough oxen, the laziest and most intractable brutes he’d ever come across. He worked hard to produce enough wheat, barley, oats and rye for the household and as a cash crop, along with peas, beans, onions and cabbages. But truth be told, Will wasn’t much of a farmer and there was much else he would rather have been doing.

From the top of the grassy knoll by the house could be seen the dwellings and barns of Foxwood village and its ancient stone church; while in the other direction, on a clear day, you could make out the stately residence of the lord of the manor, Robert de Bray. Sir Robert was seldom ever seen locally, which was perhaps partly why he was generally regarded with affection by the people of the manor, either the free or the unfree, as a decent and accommodating master – indeed the best kind of all, being little involved in their lives and allowing them almost complete autonomy in the running of their community.

A community of which young Will was a dutiful and law-abiding member. He readily submitted his various tax payments to the royal authorities who periodically came to collect them, along with the token yearly rent of one penny due to the village bailiff for the liberty to otherwise tend to his own affairs, plus the additional scutage tax the manor required in return for being excused military service. The regular supplies of cut and split firewood logs and fresh meat were the extra tithe that he paid to Wexby Abbey in return for the seven acres of the Church’s woodland and pasture licensed for his use. That was where he often exercised the skill that had earned him the name of ‘Will the bowman’, harvesting rabbits and woodpigeons and other small game thanks to his prowess with the longbow. Needless to say, the many deer that roamed Sir Robert’s own woods were strictly out of bounds to any commoner not a sworn forester of the king, as many a poacher had learned at the cost of his right hand for a first offence, blinding for those determined or desperate enough to attempt a second. But those were the laws, however harsh; and like most people, Will accepted their necessity.

On his journey towards Wexby Abbey, Will crossed the new wooden bridge over the Windrush and felt his usual satisfaction at the rumble of his cartwheels over the solid timbers. When an overladen wagon had collapsed the original rotten bridge supports under its weight during the last winter, causing its load to be scattered into the river, Will had been among the men of Foxwood who had cut and carried the replacement timber pieces and laboured for three days in the cold to rebuild it. It pleased him to think that the fruit of their efforts would outlast his own lifetime.

A little further along the road he spied a raggedy figure making its shambling way along the verge and saw with pity in his heart that it was a wandering beggar, a most pathetic and starving one at that. Halting the old grey mare Will called to the man, then from the sack in his cart he pulled out one of the dead rabbits intended for the abbey and tossed it down to him. The beggar thanked him with a toothless smile and tears in his eyes, clutching the carcass to his chest. ‘Bless you, young sir.’

‘Take care of yourself,’ Will told him, and drove on as the road gently climbed the hill up towards Wexby Abbey. Presently he was steering the mare through the ivied archway into its main courtyard, where he jumped down and tugged the bell-pull outside the smaller entrance designated for tradesmen and the like. After a short wait he was met there by Sister Edith, one of the nuns, not much older than himself and always smiling and cheery.

‘Good morning, Sister Edith,’ he said with a warm smile of his own. ‘I have brought you firewood and some fresh game for the kitchen.’

‘How pleasant to see you again, Will. Isn’t it a beautiful day, so early in the spring?’

‘As radiant as could be wished for,’ he agreed. ‘And I hope I see you in good health, Sister?’

‘By God’s grace I am well, thank you for asking. And busy helping with our preparations for Easter. How is Beatrice?’

Will’s smile widened as the mention of his wife’s name brought her face vividly into his mind, though in truth she was never far from his thoughts. ‘She’s doing fine. Counting the days.’ As was he, because during the coming summer season, in three months’ time, the couple were to be blessed with the birth of their first child.

‘I am sure it will be a boy,’ Sister Edith said. ‘And that he will be born with his mother’s beautiful golden hair and blue eyes. Not to mention his father’s courage and handsome looks,’ she added coyly, and not for the first time Will wondered if the young nun might be innocently flirting with him. As to his handsome looks, Will had never seen his own reflection in anything other than still water or polished metal and so could have no particularly well-informed opinion of himself in that regard; but from the reaction his presence seemed to inspire in some women, and the way many men either looked twice at him or avoided making eye contact altogether, he was aware that his physical size gave him a certain bearing that might be considered attractive or imposing, depending on the beholder. He was taller than most men, and had inherited his father’s broad-shouldered build and long, powerful arms, made more muscular by plying his wood axe and saw – and though (as far as he could count them) he had seen only twenty birthdays, there was nothing boyish about his demeanour.

‘For my part,’ he replied with a chuckle, ‘it makes no difference to me whether Beatrice and I are to receive a son or a daughter. Either would give us as much joy. And how happy she’ll be to become a mother.’

‘With the Lord’s blessing all will go well for her, when the time comes,’ said Sister Edith. ‘I will say an extra prayer for her every morning and every night, that mother and child be safe and healthy.’

‘That’s very kind of you, Sister.’ Reaching again into the back of the cart Will brought out the sack containing the seven remaining rabbit carcasses, five brace of woodpigeon and pheasant and the fresh pike he’d fished from the river early that morning. ‘I know it’s not much,’ he said, laying the sack at Sister Edith’s feet. ‘I had been hoping for a March hare. I spotted as big and fat a one as you have ever seen running about the top of Foxwood Hill only yesterday, but when I went back to hunt for him, he had made himself scarce.’

‘Do not trouble yourself,’ Sister Edith said, peering into the sack. ‘The Mother Superior will be delighted with these, and just in time for the ending of the Lenten fast now that Easter is almost upon us. It will be so good to taste butter, cheese and meat again, after six weeks! Thank you, Will.’

‘And here,’ he said, handing her a bulging linen bag, ‘are some more candles for the refectory. A few are made from beeswax, the rest tallow. I’m sorry there couldn’t be more, but Beatrice tires easily these days.’ Candle-making was another small industry carried out at the homestead. Naturally, the wax ones were superior, brighter and cleaner burning. Beatrice took great pride in her bees and was completely fearless when it came to collecting their produce. Will, on the other hand, was secretly terrified of the buzzing, crawling, swarming insects and was extremely reluctant to venture anywhere near the hives. So much for his great courage, he thought to himself.

‘What finely shaped candles,’ Sister Edith said, holding one up to admire it. ‘They give far better illumination than those we get from the chandlery in Wexby, and hardly any smell at all. Please tell Beatrice that she works too hard, slaving over a hot melting pot hour after hour in her condition. She needs to rest and conserve her energy.’

‘You try telling her so,’ Will laughed. ‘One might as well ask the Windrush to stop flowing. Now here,’ he said, ‘let me help you carry these heavy things to the kitchen and pantry. I have wrapped the carcasses as carefully as I could to stop any blood leaking out, though even so you wouldn’t want to get any on your habit.’

But Sister Edith’s willowy frame belied the strength she’d gained from a lifetime of hard work, and with a gracious refusal she hefted the sack and the linen bag, one over each shoulder. ‘I hope to see you again soon, Will,’ were her parting words as she turned to go back inside. ‘May God’s peace go with you. And don’t forget to give Beatrice my love.’

Moments after the nun had disappeared through the stone doorway with a final smile, Will was joined by the surly presence of old Godfrey. He was a dour, hunchbacked, one-eyed man of indeterminate age who had seemed very ancient to Will for as long as he could remember. These many years past he had been employed to tend to the abbey grounds, dig the graves in the churchyard and perform general labours. ‘Come along now, young feller,’ he grumbled, ‘you’ll have to give me a hand unloading all this lot. My poor old back ain’t doing so well today.’

The abbey’s wood and grain stores were housed in the great thatched tithe barn at the rear of the main buildings, by the ruined and moss-covered archway marking the spot where St Aethelwine’s Priory had stood in ancient times. Will held on to the mare’s bridle as she obligingly backed the cart up to the open doors of the barn. He rewarded her with a rub on the neck and a nose bag filled with oats and barley to munch on while he and Godfrey did the rest.

The two men spent the next while carrying armfuls of logs down from the cart and stacking them on the woodpile, in such a way that the older ones that had already been seasoning under cover would be at the front, ready for use. In so doing they disturbed a nest of rats, which scattered in all directions as Godfrey shouted ‘Shoo! Shoo! Hell rip and roast ’ee fucking little buggers!’ in a rising screech of indignation while he flapped his arms and leaped about the barn trying to stamp on the darting rodents, a spectacle so absurd that Will had to suppress his laughter. It was just as well Mother Matilda was far out of earshot, or else she would likely have had Godfrey clapped in the stocks for his language, and the monks pelt him with rotten eggs.

Once the logs were taken care of, they piled the bound sheaves of dry kindling sticks in a heap nearby. ‘That’s the last of them,’ Will said, dusting his hands. ‘Thank you for your help, Godfrey.’ The older man grunted something unintelligible and stumped away to attend to his other chores.

His duty to the abbey done until next time, Will climbed back aboard his cart and set off for home. The sun was warm on his head and his heart was light. At her usual plodding pace the grey mare clip-clopped away from the abbey, over the hill and back across the wooden bridge. Presently they took the right fork in the road that would bring them through the woods, and from there to the well-trodden track up to the homestead. The oak, beech and rowan buds were bursting back into leaf after their long winter sleep and the birds were singing brightly in the treetops.

As Will was passing Foxwood Hill, a faraway movement on the hillside caught his sharp eye, and reining the mare to a halt he muttered to himself, ‘God’s bones. There he is again.’

Sure enough, the big old hare he’d spied in the very same spot the previous day was back. His burrow must be somewhere nearby. As Will watched, the animal, little more than a tawny speck against the green at this distance, darted a way through the long spring grass then sat on its haunches and stayed perfectly still with one long ear cocked, seeming to be watching him from afar.

Will was all for abstaining from meat during these weeks of Lent, but he insisted on Beatrice getting the nourishment she and the unborn infant needed. Having given all his catch of the last three days to the abbey and the wandering beggar, he had left himself with nothing to take home for tonight’s supper and there was little in the larder except a few eggs, some hard cheese and stale bread. The hare would provide a welcome meal.

‘Don’t you move, now,’ Will said to his prey. He reached under the seat of his cart and lifted out his bow, along with a single arrow: his hunter’s experience told him that, hit or miss, one shot would be all he’d get at his quarry. The bow was one that Will had fashioned himself from a perfect piece of yew, in the way that his father had showed him many years ago. Likewise, he made his own arrows, all but the sharp triangular iron heads that he obtained from the smithy in Foxwood.

Moving very slowly so as not to frighten the hare away, he climbed down from the cart, braced his bow stave against his right ankle and behind his left knee. Then with his left arm he applied enough backward pressure to bend the stave far enough to slip the string up onto its notch. It was a procedure he had performed so many times that it was second nature to him. With the bow ready for use he fitted the nock of the arrow to the hemp cord. It was a powerful weapon, tailored exactly to the length and power of his draw. Will lacked a scale to measure the weight of pulling back the bowstring to its full extent, but he estimated it as not much under his own. The energy it delivered to the arrow gave the weapon a maximum range of some three hundred yards, twice the distance from which the hare, still perfectly immobile, sat watching him.

Will took a breath, fixed eyes on his quarry, raised the bow, pulled it all the way to full draw in one smooth, powerful movement and took aim. Still the hare didn’t move a muscle. It almost seemed to be taunting him. You’ll never get me from that far, my foolish friend.

But Will knew better than the hare, and had proved time and time again that he could easily hit a target half that size at this range. Then, just as he was on the verge of releasing his shot to prove the creature wrong, the hare bounded quick as a flash into the long grass, disappearing from sight.

‘Damn and blast,’ Will said, lowering his bow and letting the tension off the arrow. It seemed as though the wily old beast would live to be hunted another day, either by himself or by one of the foxes that ranged through the woods and meadows. It was in the nature of things, and Will couldn’t allow himself to be disappointed as he unstrung his bow and climbed back aboard the cart. ‘Come, let’s go home,’ he said to the mare, and she plodded on.

It was as Will was clearing the brow of the last rise before reaching the homestead that he caught the acrid smell of burning, and felt a sudden chill of apprehension go through him. And then he looked up over the trees and saw the thick, dark smoke rising into the sky.

Chapter 2

A confusion of possibilities all flew through Will’s mind. Beatrice had been taken ill, fainted or collapsed and somehow set fire to the house; or else a spark from the chimney had ignited the thatch; or a dozen other things that occurred to him all at once, all of them equally alarming. But the reality was far worse. From the direction of the homestead, he faintly made out the high-pitched whinny of a horse, the sound of a man’s voice raised in a shout. And Beatrice’s scream.

Will’s hands began to shake as he urged the mare to go faster. ‘Come on, move yourself !’ Her ears turned back towards him at the sound of his voice, but nothing short of a lashing with a bullwhip could have broken her out of her sedate pace and he knew that he’d be quicker on foot. He leaped down from the cart, grabbing his bow and arrow quiver, and ran for all he was worth the rest of the way up the track with the mare towing the empty cart behind him. His heart was pounding violently and his legs felt watery-weak with terror.

So bewildered that he could barely think or even see straight, Will reached the break in the trees where the track forked off into his own property. There were fresh overlapping hoof prints in the dirt, confirming what his ears were already telling him. More than one horseman had come through here, and very recently. As he ran on, he could hear more clearly the neighing and snorting and pounding hooves of several horses and the loud voices of their riders. Behind those sounds were the sharp crackle of flames, the screech of panic-stricken chickens and the lowing of the oxen in the barn. Above all were Beatrice’s piercing cries of distress.

And then, as he rounded the great old oak stump that marked the entrance to his yard, the sight in front of him filled him with chilling horror. The thatch of his and Beatrice’s home was blazing out of control, pouring black smoke. The yard was a scene of confusion and fury as the four horsemen who had attacked the homestead wheeled their mounts in all directions. The riders astride their tall, powerful horses were soldiers – as was instantly apparent to Will from their chain mail, iron helmets and shields. But they were soldiers unlike any Will had ever seen before. The fifty or so men-at-arms who served Sir Robert de Bray were an occasional sight in Foxwood, and everybody recognised the noble coat of arms displayed on their shields, a simple white stripe on a background of crimson and blue. The motif that Will could see on these men’s shields and surcoats was a black eagle, menacing with spread wings, a cruel hooked beak and three long tail feathers pointing downward like spikes.

Whoever they were, they had clearly come here with the intention of causing death and destruction. Three of them had drawn swords and the fourth was still clutching the flaming brand with which he had fired the thatch. Will looked for Beatrice but she was nowhere to be seen, and he could no longer hear her screams.

Will kept running, shouting at the top of his voice, but either the riders couldn’t hear him over the chaos, or their attention was too taken up with wreaking devastation on the homestead. As he sprinted wildly across the yard towards them, he saw one of the soldiers jump down from the saddle and disappear into the byre adjoining the burning house. The man reappeared an instant later, clutching a wildly struggling Beatrice by the arm. In her other hand she grasped Will’s wood axe, which she had taken from the chopping block to defend herself with. Now she swung the axe at the soldier who was dragging her from the byre; but with only one free hand it was too heavy for her to wield, and her wild swing missed him by a foot, the momentum of the iron axe head unbalancing her. The soldier easily knocked the shaft from her grip and roughly grabbed her other arm in his gauntleted fist. Her golden hair was tousled and covered her face. Her frantic cries were half drowned out by their crude shouts and laughter as a second soldier jumped from his horse to join his comrade in dragging her out into the yard. It was obvious what these men intended to do to her, even though she was visibly with child.

By now Will had almost reached the nearest of the horsemen on his side of the yard. Up close, the rider was an intimidating figure looming far above him in the saddle with the blade of his drawn arming sword glinting in the sunlight. Before Will reached him the horseman saw his approach and wheeled his mount around to face him, dust flying from its hooves. With an angry shout the rider spurred the horse towards Will, swinging his sword down at him. Will ducked, and the double-edged blade hissed through the air above him.

It had been a blow meant to separate his head from his shoulders, and it had only narrowly missed its mark. The horse thundered past, shaking the ground. The rider reined it brutally around and charged at Will again.

Nothing like this had ever happened or even been heard of in Will’s experience. He had never been in a real fight, except a minor scuffle once when he was a lad, settled quickly with a couple of punches. This was deadly serious combat, and he was unprepared for it. But the terrible shocking sight of Beatrice in the soldiers’ clutches and the sound of her screams was enough to dispel his confusion and fear, filling him with rage and determination to do anything he could to drive these raiders away and make this stop. And the obvious realisation suddenly occurred to him, for the first time, that he was holding the very means of doing that in his hands. His bow was still unstrung, no more than a long wooden shaft with its hemp cord loosely attached at the bottom end. But practice had made him very adept at readying the weapon in moments; as the horseman bore down on him with the sword raised high, he bent the stave against his foot and looped the string into p. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...