- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In this reimagining of Dickens as an amateur sleuth, Charles is tossed into Newgate Prison on a murder charge, and his fiancée Kate Hogarth must clear his name . . .

London, January 1836: Just weeks before the release of his first book, Charles is intrigued by an invitation to join the exclusive Lightning Club. But his initiation in a basement maze takes a wicked turn when he stumbles upon the corpse of Samuel Pickwick, the club's president. With the victim's blood literally on his hands, Charles is locked away in notorious Newgate Prison.

Now it's up to Kate to keep her framed fiancé from the hangman's noose. To solve this labyrinthine mystery, she is forced to puzzle her way through a fiendish series of baffling riddles sent to her in anonymous poison pen letters. With the help of family and friends, she must keep her wits about her to corner the real killer—before time runs out and Charles Dickens meets a dead end…

Release date: October 26, 2021

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 231

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

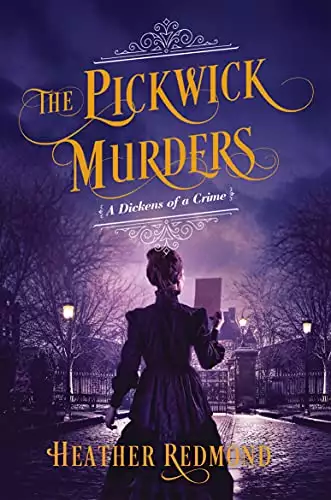

The Pickwick Murders

Heather Redmond

A bugle blared in Charles Dickens’s ear, coming from a raggedy band of marchers passing him on the way to the hustings set up in Eatanswill’s market square. Yellow-brown cockades pinned to the lapels of old-fashioned tailcoats and ladies’ capes demonstrated that these were the followers of the local Brown party, allied to the Whigs. Charles tipped his hat at a particularly pretty daughter of the voters. She went pink and put her hand in front of her mouth, then dashed to her mother’s side. Behind her straggled a couple of young boys, beating drums out of time.

To the right, another group marched between a coal distributer and a cloth merchant’s place of business, also routed to the hustings. A streaky royal purple banner attached to a bakery’s awning flapped in the bitter January wind. The cloth already shone white at the top, where a light rain had loosened the dye. This must be the Purples, allied to the Tories.

He surveyed the scene from a two-foot rock embedded next to a public house door. It gave him enough height to see across the Election Day crowd. Would the vote be for Sir Augustus Smirke, the favorite son of the Purples, or go to Vernon Cecil, the darling of the Browns? One or the other would become a member of Parliament for the first time.

Charles, parliamentary reporter for the liberal Morning Chronicle newspaper, hoped Cecil would carry the day. With any luck, a clear majority would offer its voice and the local sheriff could call the election instead of having to schedule a poll some few days in the future, in which case Charles would not be able to go back to London that night. He’d have to write his story and send it on the express mail coach back to the Chronicle offices in London.

Resounding “huzzahs” blazed into the air as another phalanx of men appeared between the buildings. He recognized William Whitaker Maitland, the new High Sheriff of Essex, leading the parliamentary candidates, who were followed by their most prominent supporters. Sir Augustus towered over Sheriff Maitland, a man well above average height, with a majestic belly to match. Mr. Cecil did not have the height, though the profusion of gray-streaked reddish curls poofing out from underneath his top hat gave him at least one measure of distinction. Charles knew him to be the son of an important local landowner, but felt unease for his prospects as age and experience were not on the Brown candidate’s side.

Shouts came from the left, displaying real alarm this time, instead of pride. A small group of horsemen galloped into the square, coattails fanned out behind them. The first man had a shotgun across his arm and the other half dozen held rakes or hoes as if they were jousters of old, ready to go head to head in battle with other knights. In their work-worn attire, they looked like they belonged to the logging or hunting trades in Epping Forest, rather than professions here in town.

The horsemen pressed forward through the crowd of locals. People jumped back or fell in their wake, moving like the windblown brown and purple banners that hung on posts jutting from some of the houses. A horse and rider knocked over a boy. The boy clutched at his foot and screamed. A man hurried to his side, grabbed him, and hoisted him into the air, settling him on his shoulders.

While Charles had been watching the intruders, the high sheriff and candidates climbed onto the hustings. The temporary stage had bunting in the parties’ colors decorating the wooden railing. A lectern, probably borrowed from St. Mary’s, a venerable medieval church on the edge of the square, was set up for speeches.

Sheriff Maitland pointed his finger at the gunman as he thundered up to the very edge of the hustings. “I see you, Wilfred Poor. You and your men are welcome to vote, but not until you hand over that shotgun.”

Wilfred Poor lifted the gun and for a moment Charles stiffened, afraid he would fire at the high sheriff. Instead, Poor fired into the air. The crowd ducked instinctively, including Charles. Initially, pandemonium reigned. But just as quickly as the crowd reacted with screams, they subsided, until the only nearby sound was a dog barking in one of the houses near the church.

Poor lowered the muzzle of his gun until it was pointing into the belly of that giant, Sir Augustus. “Where is my Amy, my daughter?” he screamed.

Sir Augustus’s lips curled, but he said nothing. A trio of his men pushed forward, as if to provoke a reaction, but Sir Augustus’s long arms spread out, holding them back.

Poor repeated his anguished query, the tendons of his neck in high relief.

“What’s wrong, Wilfred?” Sir Augustus mocked. “Can’t keep control of your own womenfolk?”

One of the horsemen chuckled and glanced at the man next to him, his expression changing at the anger in his neighbor’s face.

“You aren’t much of a man,” Sir Augustus said in a teasing lilt.

“Come now, Sir Augustus,” one of the horsemen said in a rough country drawl. “Amy’s been missing these past three days.”

“No one’s forgotten she’s your maid,” added another.

The shotgun, which Charles had not taken his glance from, shook in Poor’s hand. The horseman closest to the upset father patted Poor’s arm.

“We know you’ve hidden her away,” another horseman said to Sir Augustus. “Just give her back and we can get about this business of the election.”

“Speech,” called a brave soul in the crowd.

The horseman closest to the speaker threw his hoe in that direction. A man fell. Charles craned his neck, looking for blood spill. No one screamed this time. The high sheriff called for his men, a few local constables hovering around the edges of the bunting, to arrest the rider, but he wheeled his horse around and galloped off before they gathered their wits. One of the constables broke away for crowd control, pushing a couple of women who were attempting to climb the hustings to escape the horsemen. Another knelt next to the fallen man. The last constable raced out of the square in pursuit of the villain on the horse.

Charles whipped his head around when he heard the sheriff call out an order. Charles’s brand-new hat caught in a gust, which sent it flying past the window of the public house and down the shadowy street. He leapt off the rock to chase the expensive felted beaver cut in the Regent style. He loathed having to replace it so soon, and in a crowd like this, some light-fingered thief would grab it if he took his eyes off it for even a moment.

He reached out, his fingers just touching the brim before the hat flew again. Stumbling, he put on a burst of speed in front of the open door of a tobacconist and snatched his hat before it tumbled off the pavement and into the dirt road in front of the square.

He glanced up, grinning with his success, and saw a young man, hat lowered over his brows. The lean form and rather worn clothing caught Charles’s eye with a note of familiarity. The youth jerked. He straightened, then vanished around the side of the tobacconist’s shop, black curls fluttering around his neck.

Charles’s thoughts flew back to last summer, and a vegetable plot not far from London’s Eaton Square. Curls like that had spilled out from a straw hat worn by the young farmer, Prince Moss, so enamored of the cold, beautiful, and amoral Evelina Jaggers, the foster daughter of Charles’s deceased neighbor.

Charles followed the pavement to an alley passing behind the shop. He stepped in, figuring this was a small town and violent criminals were unlikely to be lurking in alleyways in daylight. The young man had vanished.

Charles surveyed the collection of barrels and rubbish. He heard the crackling of a fire, probably coming from the smithy that backed up against the alley. A couple of warehouses boxed in the smithy. The youth could have gone anywhere.

He turned away. His job was to follow the election, not chase men who had a clear right to go wherever they wanted. If it had been Prince Moss, he had reason not to greet Charles after the events of last summer. Charles and his friends had hoped that Miss Jaggers and her swain had left England entirely, but they were not wanted for any crimes.

He returned to his stone perch. Two local voters were carrying the fallen man from the crowd into one of the houses on the left side of the square, probably a doctor’s office. The constables were standing next to the horsemen who had remained in the square, keeping a vigilant eye on them.

Wilfred Poor had surrendered his gun into the high sheriff’s hand. He gave an anguished cry, that of a wounded animal, then swayed in his saddle, shaking.

“Why don’t you go home, Wilfred?” said Sheriff Maitland, not unkindly.

“I’ll stay for the vote,” the broken man said. “I want to make sure that blackguard doesn’t win.”

“Speech!” called a man from the crowd.

“Let’s get on to business!” cried another.

The high sheriff cleared his throat and introduced the Brown candidate. Charles took rapid notes in his best-in-class shorthand, but the speech was nothing out of the ordinary. Protect the working man, keep trade free, expand the franchise. All the usual sort of things, customized to the town’s interests.

The less-than-enthusiastic reception made Charles concerned for Mr. Cecil’s success. Then Sir Augustus was introduced as the Purple candidate. He spoke about protecting the town and the country from liberal encroachment, calling out several men in a humiliating singsong, such as a local schoolteacher he called a trumped-up peasant, and similar insults. The better dressed men in the crowd shouted “Hear! Hear!” several times and Charles had the impression of a vicar speaking to his faithful, despite the insults.

His gaze drifted to Wilfred Poor, but overall, his temperament seemed far more even than that of Sir Augustus, who, as he came to the end of his speech, was red in the face, spittle flying. He finished with his fists in the air, the crowd shouting “Protect Eatanswill!” along with him.

The mayor walked to the center of the hustings and called for a vote. The back of Charles’s neck prickled as Mr. Cecil’s name was called. He glanced around, feeling like he was being watched by unseen eyes, but saw no one.

As expected, Mr. Cecil only received a faint round of applause. Mr. Poor wheeled his horse around, the dark circles under his eyes deepening as he saw how limited the support was for the liberal candidate. One of the other horsemen still present took his arm. Mr. Poor stared at his shotgun, but obviously decided he’d never have it returned now. The horsemen left the square at a sedate walk while the high sheriff called Sir Augustus’s name.

Charles winced in disgust as the crowd of men surrounding the platform called their support. No need for this election to move to the polls. Sir Augustus had won easily, returning a Tory to Parliament for 1836.

Charles walked into the tobacconist’s shop to buy a cigar as soon as the proprietor entered from the square. He asked the man for a brief history of Wilfred Poor, and soon had an earful of his family’s mistreatment by the Smirkes. Dead wife, missing daughter, hand-wringing old mother who had quite lost her senses in despair.

Not twenty minutes later, Charles walked to the coaching inn at the edge of the main road, so he could catch the stage back to London to file his report. His editors would be pleased by his article, if not by the election’s outcome.

“Well done. It’s so pretty, Kate,” said Mary Hogarth, admiring the blond lace decorating the neckline of her sister’s new evening gown the next evening. “I can’t believe this silk was secondhand.”

Kate spread out the skirt made of spotless, unsnagged silk. “It’s lucky we visited Reuben Solomon’s stall that day. I’ll bet you this dress was only worn once. A wine stain down the front and havers, off it goes to the old clothes man.”

“It must be pleasant to be so wealthy.” Mary pinched her cheeks to bring color into them.

Kate followed suit. “Wealth comes with its own burdens. I shall like keeping our little suite of rooms with just you to help me.” Charles had agreed they would add Mary to his household after they wed, assuming Mother could spare her, which would make up a foursome then, since his brother Fred lived with him, too.

“It will be a treat,” Mary agreed.

The sisters talked about their neighbors while they dressed for the party. It wasn’t often they were invited to an evening at a titled lady’s home. In fact, they had only become acquainted with their neighbor at Lugoson House across the orchard one year before, when they had heard screams during their Epiphany Night party.

That had been the night Kate met Charles, then a new parliamentary reporter working for John Black and her father at the Morning and Evening Chronicle respectively. Little had she realized as they stood vigil in the room of dying Christiana Lugoson that she would fall so deeply in love with him less than two months later.

Both of Kate’s parents and their parents before them had travelled in distinguished literary circles, first in Edinburgh and now in London, but with someone like Charles joining the family, they had acquired new status and important friends. Charles had a brilliant future ahead of him and Kate could scarcely believe she was the wife he had chosen. He had promised they would wed in the spring. In a few weeks, they would ask for the banns to be called at St. Luke’s down the street. Soon, she would be his and he, hers.

The door rattled, then opened. Georgina, eight years old and bursting with self-importance, announced, “Charles is downstairs and everyone is ready to leave.” They followed Georgina out of the room the sisters shared, excepting little Helen, and went down to the dining room where the family always gathered.

When Kate walked into the dining room and saw the thick dark locks, bright hazel eyes, and full lips of her fiancé, her face went so hot that her cheeks reddened of their own accord. She drank in the sight of him.

He spotted her and sketched a bow. She curtsied with a laugh, and then he touched her hand. A tremor went through her at the press of his flesh to hers. She could scarcely wait for spring.

Her mother sorted the older from the younger children with a no-nonsense air, then her father led the way to the front door and down to the street. Kate held Charles’s arm on the pavement, even though she was in no danger of slipping. The rain had held off, though the air was bitter cold. Conveyances rolled by on the street, out of sight, holding other revelers.

Mary, on the other hand, stayed close to her mother. Kate knew her sister feared giving Fred, a year younger, too much attention. Fred had tender feelings for her, but Mary considered the young man a child, even though he had a position at a law firm now.

A liveried footman had the door of the renovated Elizabethan mansion open when they came up the steps, as another party was ahead of them. Kate recognized Lord and Lady Holland, quite the grandest personages she had had occasion to know.

The Hogarth and Dickens party passed through the doors behind the Hollands. The old-fashioned front hallway still had wood paneling, though Lady Lugoson was slowly modernizing the premises now that she’d committed to staying in England. Any visitor’s eye went immediately to a double staircase directly ahead of them, but Lady Lugoson did much of her entertaining in the long drawing room that looked out over her formal garden.

After they left cloaks behind and the ladies changed shoes, the footman took them to the room’s entrance and Panch, the venerable butler, announced each party in turn. Few paid attention as the room held quite a crush of people.

Still, Lord Lugoson, just sixteen and home from school, dashed up to greet them, and seemed happy to meet Fred Dickens for the first time. He took the lad off to meet other youths.

Kate spotted Charles’s fellow reporter, William Aga, standing next to the closer of the two fireplaces heating the room. Charles tilted his head at Kate and they disengaged from her family to greet the Agas.

Kate’s father did not like Julie Aga, William’s wife, who had once trod the boards and tended to create complications. But Kate and Julie were often thrown into each other’s company and had come to terms.

“Excellent reporting,” William exclaimed, thumping Charles on the back as soon as he was close. William, tall and athletic, had a ready smile that everyone responded to. His reporting focused on crime for the Chronicle. Julie, red-haired and lovely, scarcely showing her pregnancy yet, took Kate’s hand and squeezed, her eyes dancing merrily as she took in the new gown.

“Part of your trousseau?”

“No,” Kate said, blushing. “But I am working on that.”

Lady Lugoson, an ethereal blonde, approached them on the arm of her baronet fiancé, the coroner Sir Silas Laurie. Her gown was cut much lower on the bosom than Kate’s, and had few decorations. The beauty lay in the perfection of the best black silk, with a white silk and lace underskirt. Kate saw Charles’s gaze dart over the gown, then he inclined his head.

“I read your latest article, Charles,” Sir Silas said. “Very dynamic. I wonder that your Mr. Poor did not assassinate Sir Augustus right at the hustings, given the fervor of your descriptions.”

“Sir Augustus is dreadful,” Lady Lugoson interjected with a toss of her head. She had been a political hostess while her first husband had been alive. “How unfortunate it is that he won the election.”

“Do you know him well?” Charles asked. “He is a conservative.”

“Sadly, he was a friend of my late husband.” Lady Lugoson’s soft mouth turned down. “They were at school together and remained close.”

Kate winced. Everyone knew the late Lord Lugoson had been an evil seducer, with just enough charisma to charm the families of his victims. The future sounded bleak for that Mr. Poor’s daughter. The shotgun-wielding assailant might be correct in his assumption that Sir Augustus had taken her. “Such dangers you find yourself in,” she murmured to Charles.

“Have done,” Charles said with a chuckle. “There were hundreds of men in the square, and not a few women and children. I was nowhere near the gun.”

As her father came alongside Kate, William said, “I should report on the missing girl for the newspaper. Maybe I can find her.”

Her father cleared his throat. “We couldnae print the story. We may be a liberal paper, but that is reaching too far, even for us.”

Julie frowned. “What can be done to help the unfortunate girl?”

“Nothing until she is located,” Kate rejoined. “I wonder if Sir Augustus will bring her to London?”

Charles’s head felt a bit dim the next morning, the possible consequence of too much cigar smoke and rum punch at the Epiphany party. It had been a jolly night however, and unlike the previous year, no one had died.

He arrived at the Morning Chronicle newsroom at 332 Strand almost on time the next morning. After greeting his fellow reporters, he found a messy pile of correspondence on his desk. The letters included an offer of work at an inferior newspaper, a letter from a member of Parliament thanking Charles for quoting his speech properly, and a note from William Harrison Ainsworth, inviting him around for dinner that night.

He ignored the rest of the pile and dipped his pen into his ink pot to scrawl a note at the bottom of the note, expressing his regret that he could not attend dinner with the popular novelist. He suggested he reschedule for some time next week. That night, he and Kate were promised to a member of Parliament’s dinner party.

Charles blotted the note and sealed it up, then set it aside for one of the office boys to send. Tom Beard, who had helped him procure this job two autumns ago, winked at Charles as he passed by. Charles watched his friend until he was half turned around.

“Hate mail,” William Aga remarked, tossing down a letter and pushing his chair backward until it bumped against Charles’s chair.

“From who?” Charles asked, extricating his legs from the position they’d become tangled in.

“Newgate Prison,” William said with a shake of his head. “You would think a prisoner would better spend his money on lawyers than complaining to members of the press.”

“I have nothing so exciting,” Charles said, reorienting his chair before flipping through the rest of his pile. He spotted a very fine piece of linen notepaper, addressed to Charles Dickens, Esq. The seal was so large it might have covered a gold guinea, as some people did to send funds to relatives. “I may have spoken too quickly.”

William leaned over the letter, exposing Charles’s olfactory senses to the pomade separating his friend’s tawny curls. He poked his ink-stained finger on an emblem centered on the seal. “This is from the Lightning Club.”

Charles sat back, then bent forward again. He didn’t know what to do with his hands. His fingers danced nervously on his thighs. “The Lightning Club? You don’t think I’m being offered a membership, do you?”

“Why would you be offered a membership in such an exclusive organization?” William quizzed, lifting his finger from the letter. “Surely they have writers in their distinguished collection of followers.”

Charles shrugged. John Black, the Morning Chronicle’s editor, walked by, but didn’t stop at his desk. “Then what else could it be? An invitation to speak?”

“An invitation to report on a meeting?” William suggested. Always fastidious, he wiped his finger with a handkerchief and tucked it neatly away.

“I wouldn’t be asked to do that. They aren’t political. Their members are prominent in the sciences. And in poetics, sportsmanship, art.”

“Hmmm,” William mused. “Maybe they don’t have any great parliamentary reporters.”

Charles poked his elbow into William’s ribs. As his friend pretended to gag, he slid his letter opener under the seal and opened the trifolded note. He stared at the contents, his body filling with prideful warmth.

“Well?” William prompted.

“Unlike you, they see my greatness.” Charles grinned at his friend, feeling a boyish degree of excitement. “I’m invited to join the exclusive Lightning Club.”

“I wonder why,” William said in a wry tone.

Charles shrugged with an insouciant air. “With my first book of sketches about to release, I’m getting noticed and rising in the world.”

William’s upper lip curled up. “Excellent.”

Charles glanced at the note again. He was supposed to attend an initiation ceremony that evening at eleven p.m. How very upper-crust. No workingman would keep those kinds of hours. He’d have to ask Fred to escort Kate back to Brompton so that he could attend. He wouldn’t miss this for the world.

“What’s that?” John Black said. He’d made it to Charles’s desk without him noticing.

“Charles has been offered membership in the Lightning Club,” William explained.

“You don’t say.” Black nodded thoughtfully. “A prestigious organization. I’ve always believed in you. It’s good to know others have the same high opinion.”

Charles puffed out his chest. “Yes, sir.”

“That Eatanswill election article has created a considerable amount of interest,” the editor said. “Word is out that the famed Boz wrote the piece. A great number of strongly worded letters in the post this morning.”

“I was faithful to the experience,” Charles said, wondering how the Lightning Club had tied his literary nickname to his real name.

John Black stared off toward the door out of the newsroom. “I appreciated the vivid language. However, I was disappointed the Tory candidate won.”

“We’ll get the next one, sir,” Charles said.

“Back to work, back to work now.” The editor waved his hand and moved to the next desk.

“I don’t think Mr. Black really noticed I was still here,” William said thoughtfully. “Perhaps I had better try my hand at a novel.”

“Any ideas?” Charles asked.

“Something about a dastardly member of Parliament,” William said. “Murder in a gloomy old country seat?”

“I can’t wait to read it,” Charles enthused. “But set it in the past since historical novels are all the rage.”

“Less likely to anger people,” William agreed. “Why, no, Sir Nonsensical, I did not base that character on you. Did you not notice George the Fourth covering the throne like a great pudding in my volume?”

Charles laughed. “Exactly. You’ll make your fortune.”

That evening, Kate exited a carriage in Queen Square, Charles’s arm firm under hers. The warmth of his flesh under his glove soothed her chilled skin, battered by the January ride in an open cab. They were attending a political dinner down the street from St. George the Martyr church. Kate always enjoyed being his companion for these events and longed for the day when she’d be introduced as Mrs. Dickens, instead of merely Miss Hogarth.

A middle-aged man in a fur-collared coat lifted his cane as he hurried into the street. He held a doctor’s bag in the other hand. “Hold, please.”

Charles nodded at him, then the doctor climbed into the carriage. While Charles paid the driver, Kate glanced around. She hadn’t been in this part of Bloomsbury before. While the buildings around them seemed plain, she understood the views from the square were exceptional, if it were daylight and not winter. She supposed that helped the invalids housed on the square to recover their health and wits. King George III had been treated in one of the houses here, so they must have very fine medical men. She watched the doctor in the carriag. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...