- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

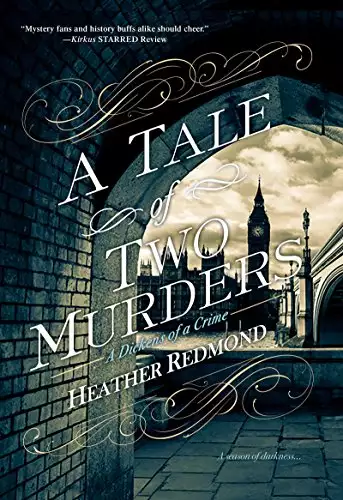

Synopsis

On the eve of the Victorian era, London has a new sleuth . . .

In the winter of 1835, young Charles Dickens is a journalist on the rise at the Evening Chronicle. Invited to dinner at the estate of the newspaper's co-editor, Charles is smitten with his boss's daughter, vivacious nineteen-year-old Kate Hogarth. They are having the best of times when a scream shatters the pleasant evening. Charles, Kate, and her father rush to the neighbors' home, where Miss Christiana Lugoson lies unconscious on the floor. By morning, the poor young woman will be dead.

When Charles hears from a colleague of a very similar mysterious death a year ago to the date, also a young woman, he begins to suspect poisoning and feels compelled to investigate. The lovely Kate offers to help—using her social position to gain access to the members of the upper crust, now suspects in a murder. If Charles can find justice for the victims, it will be a far, far better thing than he has ever done. But with a twist or two in this most peculiar case, he and Kate may be in for the worst of times . . .

Release date: July 31, 2018

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 353

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Tale of Two Murders

Heather Redmond

“Epiphany is truly the best of times,” Charles Dickens exclaimed as his hostess carried a beautiful jam tart over from the sideboard. The enormous dessert, decorated traditionally for the holiday with star-shaped pastry and thirteen different-colored kinds of jam marking the six points, enticed with fruit and sugar scents.

Mrs. Hogarth’s large family applauded as she set her creation in the center of the dining table, on top of an embroidered cloth depicting the Three Kings visiting the Christ child. Candlelight glittered over the egg-wash pastry, making Charles’s mouth water, despite the tasty meal of roast, potatoes, and cabbage they had already finished. At the head of the table, George Hogarth hefted a clean knife, almost slicing off his bushy side whiskers.

“No, sir, it is the worst,” teased his daughter, pretty Kate Hogarth, seated at Charles’s side. “For, Father must bring home guests with whom we have to share my mother’s lovely tart.”

“You shall have your favorite jam,” Charles promised, staring into the bright blue eyes of the nineteen-year-old daughter of the house. He’d been talking business with the coeditor of his newspaper all through the meal, but his eye kept alighting upon this fair maiden, despite the dozen other adults and children in the room. “Which one is it?”

“Gooseberry,” she said with a blush. “But you must have your first choice. Why, you are Father’s guest.”

“I am only a new employee of the Evening Chronicle,” declared Charles, “scarcely worth noticing.”

“Fie,” George Hogarth said, settling his free hand across his waistcoat. “Ye are our most promising journalist. To be so accomplished at a mere twenty-two years of age. Gives me hope, my lad.”

“How exciting,” Kate Hogarth said, eyes sparkling. “You must tell us what you’ve been writing about, Mr. Dickens.”

When the initial sounds of approval from her children had diminished, the matriarch, Mrs. Hogarth, a decade younger than her graying husband, slid the tart down the table to him. Charles regaled them with the tale of a recent parliamentary debate he had reported upon, complete with a falling-down drunk Member of Parliament, a sneezing man-at-arms, and a speech that went on for three hours, until one poor elderly statesman, napping away, fell off the bench, after snoring so loudly that half the crowd was in hysterics.

By the time he had finished his tale, Miss Hogarth had clutched his sleeve to keep herself upright through her convulsive giggles. He was proud of his tailcoat with its black velvet collar. His gaze moved between her fingers, sliding on the new fabric, and the toothsome sight of the pie being sliced.

He turned guiltily toward his host, his dining companion on the opposite side. His stares were improper, but such a tempting morsel had never yet been set before a young man on the rise.

“What would ye like, Charles?” asked Mrs. Hogarth.

“One of the red ones, please,” he enthused. “Miss Hogarth would love the green.”

“Same as her mother,” Mr. Hogarth said comfortably. “She does make an excellent gooseberry.”

“Did you have a good Christmas, Mr. Dickens?” Miss Hogarth asked. Her Scottish accent was less pronounced than that of her parents. “Did you see your family?”

Charles took his plate of tart. The red jam was tucked inside a triangle of pastry. “My father is out beyond Hampstead, but the rest of the family is nearby. My brother Fred lives with me, in fact. I’m to supervise his education. My mother has her hands full with my two sisters and the two youngest, both boys.”

“How nice to have family with ye,” Mr. Hogarth said, as a child, perhaps four years old, climbed into his lap and burped loudly. “How old is Fred?”

“Fourteen.” Charles grinned. “We had an excellent meal for my mother’s birthday just before Christmas. But mostly I worked through the Twelve Days. I write for more than one newspaper, and since I am not a family man, it seemed best to take all the work I could, and relieve those with little children at home.”

“Very decent of ye, sir,” Mrs. Hogarth said, from the opposite end of the table, where she bounced a babe with enormous dark eyes on her knee. “But I am so glad ye could be with us tonight.”

“Thank you for having me,” Charles said, before turning irresistibly to the girl at his side. “Tell me, Miss Hogarth, when did you come here from Edinburgh?”

“About four years ago,” she said. “I don’t seem to have lost any of the Scottish in my voice.”

“I find it charming,” Charles declared. “It is easy to see that your family is a musical one, with the sweet tones of your voice and those of your sisters.”

“We should have music when we are finished,” Mr. Hogarth said, removing the child from his leg and finishing his dividing of the tart. “But you have a long walk home, I know.”

“Where do you live?” Miss Hogarth asked, as her father passed out the final plates.

Charles watched the tart spread across the table. He had nothing like this in his bachelor lodgings, and his mother didn’t have the money to prepare such treats either, with her husband on the run from his financial difficulties. “I live in Holborn, at Furnival’s Inn. It’s a quiet, rather gloomy place, nothing like here, with all the gardens and orchards surrounding your house. We live in close contact with our fellow man.”

“As do we,” Miss Hogarth said, pulling at a red ribbon that had come untied on the sleeve of her green dress. “See how many brothers and sisters I have?”

“My family is not small either,” Charles said. “But how wholesome is it to feed your family from your own plot?”

“That is why I can make such lovely jam,” Mrs. Hogarth said. “With Kate’s help, of course.”

Her daughter’s lips curved with her mother’s praise, but then her eyebrows went up and her mouth rounded into shocked surprise.

Charles heard the disturbance as well. It came from outside the snug house. “What was that?” He swiveled around toward the heavily curtained windows.

“Sounded like a scream.” Mr. Hogarth set down his knife and rose.

He, Charles, and Miss Hogarth went to the window. Mr. Hogarth tied back one side of the winter-weight curtain so they could see. Charles cupped his eyes with his hands, trying to peer into the gloom, but mist had risen, undulating over the fallow vegetable beds. He couldn’t see anything but the ghostly branches of distant, leafless apple trees, waving in the breeze.

Another scream. Miss Hogarth jumped and shivered.

“Who lives in the next house?” Charles asked.

Mr. Hogarth frowned. “It’s a fine mansion. Lady Lugoson, a baron’s widow, returned from France with her two children a few months ago.”

“A widow alone?” Charles’s voice sharpened. These houses were spread apart. Any amount of mischief might take place with no one noticing.

Mr. Hogarth nodded, his expression concerned.

“We must go to them,” Miss Hogarth said, with an admirable sense of purpose.

“Mrs. Hogarth, will you light us a couple of lanterns?” her father suggested.

“Of course.” Mrs. Hogarth tucked a stray lock of brown hair behind her ear and hurried away.

The younger children chattered as Charles and Miss Hogarth went to find his outer coat and her mantle. She pulled off her evening slippers, and he stealthily admired her small, narrow feet in the moment it took her to find her boots and pull them on. How perfectly made she was, and how far above him. This girl had never experienced a moment’s want, never had a father in debtor’s prison or seen her brothers forced out of their education into warehouse jobs.

Charles recognized Mr. Hogarth’s coat on a hook, along with their hats, and brought them back to the dining room. As soon as Mrs. Hogarth had delivered the lit lanterns, they walked through the green baize door leading to the kitchen, startling a young kitchen maid, and made their way out of the door closest to the garden.

Across the field floated more cries, dampened and spread by the mist. “Are they being murdered?” cried Miss Hogarth.

“I can differentiate between three different females,” her father said.

Charles knew the man was a musical genius and trusted in his abilities. “Are they in pain?”

“Distress, certainly.” Mr. Hogarth pulled a stout walking stick away from the stone wall.

Charles and Miss Hogarth followed the older man as he walked around vegetable beds and pools of rainwater, mist nipping at their ankles. Only Miss Hogarth had appropriate footwear, though Charles, with necessary economy, had shoes suitable for long walks. The polish he’d painstakingly applied the previous evening would never survive this damp walk.

They reached the edge of the garden and moved into the orchard, all dirt underfoot, encrusted with the decaying leaves of fruit trees.

“May I?” Charles asked, pointing at a branch just barely attached to an apple tree.

Mr. Hogarth coughed and nodded. “Of course. I should have thought more of weapons.”

“Oh, Father,” Miss Hogarth exclaimed. “Surely we don’t need any.”

Charles tore the branch from the tree. As long as his arm, it might hold up in a fight. When he saw another branch a few feet away, already on the ground, he handed it to her.

“Goodness,” she said, her eyes wide. But she took it, stout-hearted, and carried the makeshift weapon the rest of the way.

When they had moved past the orchard mists, light from the mansion came into view. They stepped into a formal garden from the Hogarths’ apple grove. A gravel path was set among boxed hedges. Charles tried to imagine the shape of them, wishing he could see from an overhead perspective.

He had viewed the front of the house earlier as he’d walked by with Mr. Hogarth, and had examined it carefully, always cataloguing information he might be able to use in an article. The house, formed in the shape of an E, had been built in the Elizabethan age, though it had been added on and modified over the years with stone. In excellent condition, it spoke of wealth if not taste.

Now, however, they walked onto a paved terrace along the side of the house. Through glass-paned doors they could see a number of people moving around frantically in the room beyond, black-dressed maids carrying towels, footmen in formal evening livery moving toward a fixed point out of sight. Charles viewed the modern carpet and pale apple-green paint, though the newer, robust furnishings were mixed in with late Georgian pieces from the turn of the century. Mr. Hogarth opened one of the French doors.

On a sofa, Charles saw a richly dressed elderly lady, seated next to a bespectacled gentleman about ten years younger.

The middle-aged gentleman peered over his glasses and offered a polite “Good evening.”

After all the screaming they had heard, the polite, German-accented phrase seemed utterly out of place.

As Mr. Hogarth greeted the man, Charles was distracted by a raised voice. In front of a second fireplace lay a young girl, perhaps a couple of years younger than Miss Hogarth. Her head rocked from side to side, as if she was coming out of a faint. Towels covered something on the floor next to her, and he could smell ill-favored scents wafting from that part of the room. The girl must have been sick before collapsing.

Miss Hogarth put her hand to her nose as the odor assaulted her senses.

A slender woman, about a decade older than Charles, knelt at the girl’s side. She matched the drawing room paint in her dropped-shoulder gown of white silk embroidered with green leaves, but as she moved, he saw her skirt was marked with cinders at the knees. Her hands gestured above the girl, as if imploring her to rise.

Two female companions stood by the woman, one in a dinner dress that was out of style, its ruffled skirt a dead giveaway for fashion of the previous decade, the color an unflattering shade of yellow. The woman on the right, who had the familial look of an adolescent girl Charles’s gaze had passed over in the middle of the room, made more of a concession to fashion and feminine appeal in her dress, with a lower-cut bodice and tightly fit waistline.

Given the tableau, he expected the woman kneeling was the baron’s widow. The girl, now blinking her eyes, had blond hair the shade of angels’ wings. Along the wall to the right of the fireplace leaned a boy in mid-adolescence, looking more confused than anxious. The kneeling lady was also blond and Charles recognized that the slanted nostrils of her nose matched the boy’s. This then, was likely to be young Lord Lugoson, for some reason not away at school.

Miss Hogarth did not pause but, admirably, went straight to the kneeling woman after setting her stick against the wall. “My lady, I am Miss Hogarth from next door. We heard the screams from our house.”

As the woman lifted her gaze and blinked at Miss Hogarth, Charles noted her wide-spaced gray eyes and high cheekbones, along with an elfin chin. A lovely lady, he suspected she would not be a widow long.

In contrast, the other two women were a bit older, with skin just starting to sag at the jawline and under the chin. The less fashionable of them seemed to be in a near faint herself, but the other watched two footmen closely as they stepped to the head and feet of the young girl. The maids they had seen through the terrace doors had already vanished.

“Can you rise, Miss Lugoson?” Miss Hogarth asked. “Or do you need these men to help you?”

“Oh, she mustn’t try herself,” Lady Lugoson said. “She fainted dead away.” She gestured vaguely toward the towels.

“Hit the floor before anyone could catch her.” Young Lord Lugoson spoke in tones of admiration. His limbs looked too spindly to carry the minimal weight of the girl.

The footmen seemed afraid to touch the girl. Impatient, Charles went to one knee on the other side of the lady, letting his branch fall to the carpet. “I’ll be happy to carry her, my lady, if your men will not.”

At a nod from Miss Hogarth, Charles gently slid his arm under the girl’s knees while Miss Hogarth helped her sit up. Charles slowly stood with his burden. He wasn’t a large man himself, but the girl was slight.

One of the young footmen seemed to come to his senses then. He took a three-pronged candelabrum from the mantelpiece and led the procession away from the foul-smelling floor. Miss Hogarth walked next to Charles and her father joined them, trailed by Lady Lugoson and the second footman.

“Please, my lady, take my arm,” Mr. Hogarth said, solicitous. She leaned heavily on him, a bent reed, as Charles followed the footman into the passage. The girl relaxed in his arms, seeming mostly unconscious still.

“Would you mind taking her to her chamber?” Lady Lugoson asked. “She’ll be more comfortable there.”

“Of course,” Miss Hogarth assured her. “Mr. Dickens won’t mind, I’m sure.”

Charles felt his awkward burden instantly lighten under Miss Hogarth’s affectionate gaze. The girl in his arms was calm. She smelled of cloying floral perfume and sweat.

They went up the grand staircase to the first floor, and then continued up to the second. The carpet on this floor was a dusty rose color and few candles were lit to guide the way, unlike downstairs.

The third door on the right was open. Inside was an unadorned chamber, mostly taken up with a large bed. Charles noted an ancient, blackened chest and a washbasin on a simple table. A woman, who must be Miss Lugoson’s lady’s maid, sat in a hard-backed chair next to the chest, sewing lace onto a handkerchief’s edge. She was a plain creature of about thirty years and her eyes widened in alarm as the crowd entered.

Miss Hogarth rushed from Charles’s side to pull back the blankets. When she stepped aside, Charles set the girl on the mattress. The young lady tossed her head from side to side and then settled.

Instead of pulling away, Lady Lugoson clutched Mr. Hogarth’s arm even more tightly, dragging him toward the bed and the girl upon it, still in her white evening dress, as tightly cinched as her mother’s.

“I will help her maid ready her for bed,” Miss Hogarth said. “With your permission, my lady? I am used to caring for my younger sisters.”

The woman smiled faintly and nodded. “Agnes will assist you.”

Mr. Hogarth nodded in his kindly way at the distressed baroness. “Then we shall return to your guests. Perhaps you should post a footman outside the door to be ready to bring messages or whatever they might require?”

“An excellent notion,” Lady Lugoson said after a pause. She nodded at the first footman. He placed his candles on the table next to the bed, then led most of the group out of the door.

Charles smiled in the direction of Miss Hogarth, but the efficient little nurse had not even taken off her mantle, much less noticed him, as she bent over her charge.

“Such a capital girl, your daughter,” he said to Mr. Hogarth.

“She’s an excellent child. Never any trouble to her mother or me.” He turned to the distressed girl’s mother. “I hope your daughter doesn’t suffer so often, my lady.”

“No.” Lady Lugoson put a small handkerchief to her eyes. “This is very strange.”

They returned downstairs to find the elderly lady and her German companion in the hall. Lady Lugoson’s butler helped them into furs and cloaks.

“Thank you so much for coming, Lady Holland,” the hostess said.

Charles did a double take. This was Lady Holland? Why, she was famous, both in political circles and for her naughty past. Charles and Mr. Hogarth waited until the guest departed, then followed Lady Lugoson back into the drawing room.

He counted five people still gathered there. Lady Lugoson walked across the room to the second fireplace. “Mr. Hogarth, may I present my son? I am afraid I do not know the name of this young man who has been so kind.”

“Of course, my lady,” Mr. Hogarth said. “This is Charles Dickens, an employee of ours at the Evening Chronicle. Perhaps ye know that I am coeditor there.”

Charles bowed his head, happy to see the towels and whatever they had covered had vanished in their absence from the room, along with their makeshift weapons.

“A pleasure. Yes, I did know your profession, Mr. Hogarth,” Lady Lugoson said. “I have met your wife and two of your daughters. They called here one afternoon when I was at home.” Lady Lugoson held out her hands to her son. With a sulky air, the boy set aside a scrapbook in his lap and stood. Charles saw the scrapbook was thick with clippings, and on the cover was an engraving of a theater’s interior. Drury Lane, most likely.

“Lord Lugoson,” the lady began speaking to the boy. “May I present the distinguished journalists Mr. George Hogarth and Mr. Charles Dickens. Mr. Hogarth is our new neighbor. And gentlemen,” she addressed Charles and Mr. Hogarth, “that was my daughter, Miss Christiana Lugoson, whom you aided.”

“You are interested in the theater?” Charles asked, after they greeted the young lord.

“Oh yes,” Lord Lugoson said, his expression animated for the first time. “We have a relative who has a theatrical calling.”

Charles kept his eyebrows in a neutral position with difficulty. While a couple of formerly theatrical ladies had married into the aristocracy, rarely would such a family advertise any relationship to the theater.

“Yes,” Lady Lugoson said, in a faded tone very different from before. “The children do love the theater. They collect paper sets of famous productions.”

“I like the opera best, especially Mozart,” the boy said eagerly, his voice cracking. He had a wide mouth and rather large teeth set in a narrow jaw. “But Christiana prefers Shakespeare.”

“I share your interests,” Charles said. “But tell me, what happened here tonight? From the screams, we were afraid murder was afoot.”

“Christiana lurched through the room like a figure out of a play,” Lord Lugoson announced. “Then she cast up her accounts and collapsed to the floor. Rather thrilling, really.”

His mother stared at the lad, her mouth pulling down, aging her face. He cleared his throat awkwardly and went back to his scrapbook.

“I am Eustace Carley,” said a man who had been in the middle of the room earlier, coming toward them. Carley, a man with overblown salt-and-pepper hair and a grizzled moustache, wore a waistcoat straining at the buttons. He had the arm of the better-dressed woman in his meaty clasp. While Mr. Carley appeared to be around fifty, his wife still had the tiny waist and brown hair of a younger woman, perhaps in her very late thirties.

“A Member of Parliament, if I am not mistaken.” Mr. Hogarth nodded to him.

“Yes.” Mr. Carley inclined his head. “We are near neighbors, as my wife prefers our country residence to our home in Grosvenor Square, and were invited for the Epiphany meal.”

“My daughter is a particular friend of Miss Lugoson’s,” said Mrs. Carley. The gems in her gold drop earrings sparkled with the firelight.

“Is she much better now?” squeaked Miss Carley, the couple’s daughter, whom Charles had seen standing in the middle of the room earlier. She had taken the seat next to a harp, and her hands moved restlessly in her lap, fingers clutching and un-clutching. Her gown fit her poorly, as if someone had merely pinned her into one of her mother’s castoffs. Despite her creamy skin and pink cheeks, she was not pretty, and her hair color could not be described by any term more accurate than “mousey.”

“Oh yes, my dear. She needs only to rest.” Lady Lugoson’s smile was gentle.

“I cannot imagine what happened,” said the less fashionable woman in yellow, moving toward them. She was slightly older than Mrs. Carley, and had silver streaks in her black hair. “She seemed quite herself when we first arrived.”

“This is Mrs. Decker.” Lady Lugoson gestured in the woman’s direction. “Another neighbor, beyond the Carleys’ house. I know your husband had to be away this evening.”

“He is in New York,” Mrs. Decker said, pride marking her voice. “A cousin of his died and he is sorting out the poor man’s affairs.”

Lady Lugoson nodded. “If you’ll forgive me, I must speak to Panch and order fresh tea. We all need a restorative.” She rushed off, looking flustered.

“Lady Lugoson was a well-known political hostess, as I recall,” Mr. Hogarth said.

“She was during the late Lord Lugoson’s day,” Carley said. “But he shuffled off this mortal coil nearly two years ago now and she took the children to live with her aunt in France for some time. They have only recently returned.”

They spoke of the past glories of the House of Lugoson, Charles wondering all the while why the Hogarths hadn’t been invited to this gathering when the other neighbors had been. Not high enough in the instep, he supposed, despite their nearby home.

Lady Lugoson returned and begged everyone to seat themselves in a squared-off area in front of the first fireplace, furnished abundantly with sofas and chairs, leaving her son near the second fireplace. The Carley girl whispered in her mother’s ear, then left the room.

“I am only just reentering society.” Lady Lugoson’s tone was musing as a maid brought fresh tea. “I am sorry to have my first party end like this.”

“Are you as concerned about social reform as your late husband?” Mr. Hogarth asked.

“Oh, yes.” She put her hands to her cheeks. “I’m particularly inclined against the workhouse system. So dreadful, the new Poor Law Amendment Act of last year. I keep my son in London so he can see things as they really are, instead of locked away with other boys of his class.”

The butler, some forty years older than the footmen, entered the room, looking even more distant than before. Lady Lugoson frowned. “Excuse me.” She stood and walked toward her servant as the man didn’t seem to want to come closer.

The butler lowered his head on its long stalk of neck and spoke into her ear. Her eyes widened and her face went pale. Charles read some calamity on her expressive face.

Instinctively, he rose and went to her side. “What has happened, madam? May I be of some assistance?”

“Christiana has taken ill again,” she whispered, fingering her garnet pendant necklace. “Oh, Mr. Dickens, I must go to her.”

She took a step, but then seemed to falter.

“I’ll go with you,” Charles said. “We must not delay.” Had the girl fainted again, while lying on the bed? Or had she risen and paid the consequences of ill health?

Lady Lugoson took Charles’s arm as she had taken Mr. Hogarth’s before. Panch led them, trailed by Miss Carley, who was sobbing loudly, back to Miss Lugoson’s room. The footman had disappeared, and the door was open. Charles peered inside the room.

“What happened?” he demanded, taking in the pale, panting face on the bed as he stepped in. He glanced back. Miss Carley followed him in, wringing her hands, tears dripping off her nose. Miss Hogarth leaned over Miss Lugoson on the opposite side, dotting her forehead with a square of cambric. She lifted her face and joined her gaze to Charles’s, then a moan returned her attention to the wretched figure on the bed.

Charles pulled his arm away from Lady Lugoson, and pointed his finger at Agnes.

“I went to the WC, sir.” The maid, frizzy hair in disarray, let out a sob. “When I returned Miss Christiana was like this.”

“Call for a doctor,” he said.

No one moved. He turned around, hoping the butler was still in the room, but he had vanished. Taking the maid’s cold, callused hand in his, he stared into her eyes. “Fetch a doctor. Miss Lugoson needs medical attention.”

An hour passed. The butler had come and gone after receiving orders to call for more doctors. Charles sat in the corner, as unobtrusive as the maid, wincing at the sight of the girl writhing on the bed, complaining about stomach pains and nausea. He felt unable to leave, as the household seemed generally indecisive. Miss Hogarth stayed at the bedside, sponging sweat from Miss Lugoson’s brow and praying with her. Charles admired her steadfast support, even as he mentally composed an article for the Chronicle about the tragic scene.

Eventually the situation worsened. Miss Lugoson lost the contents of her stomach repeatedly, weakening with each blow to her fragile frame. One doctor came, then another. None of the remaining guests appeared ill. The Deckers and Carleys went home during the second hour of the ordeal, after Mrs. Carley sent up a maid to call mousy and hysterically sobbi. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...