Blackouts

In the beginning was a long, unexpected five-hour blackout. Caracas looked like an exposed anthill. Despite the canceled meetings, the uncashed checks, the decomposing food and the collapse of the subway system, Miguel Ardiles remembers that day with an almost fatherly affection: the city felt the shock of finding itself both cave and labyrinth.

In the months that followed, as the blackouts recurred, the city’s inhabitants began to paint their first bison, using stones to mark out familiar bends. Then the government announced its plan for power rationing. Opposition spokespeople were quick to draw comparisons with Cuba during the nineties, claiming that its energy-saving policy during the Special Period was identical to the one soon to be enforced in Venezuela.

The announcement was made at midnight on Wednesday, January 13, 2010.

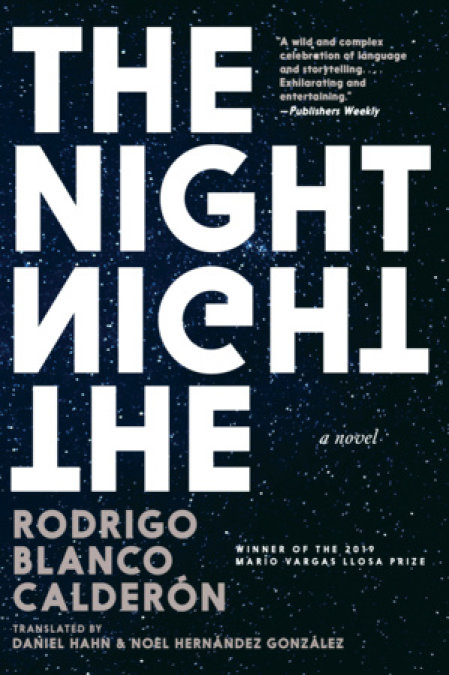

Two days later Miguel Ardiles met up with Matías Rye at Chef Woo’s. As he did every Friday evening after his last patient of the day, Miguel waited for Matías at this Chinese restaurant in the Los Palos Grandes neighborhood. Matías Rye ran creative-writing workshops at a local high school and was about to start his most ambitious project yet, The Night: a crime novel that would restore the genre to its Gothic origins. He had borrowed its English-language title from a Morphine song, and hoped to translate the nuances of the band into his writing: entering the horror like a person slowly falling asleep, turning their back on life.

Rye claimed that the classic crime novel was dead.

“Things go full circle from ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue,’ in 1841, to ‘Death and the Compass,’ in 1942. With that one short story, Borges effectively finished off the genre. Lönnrot is a detective who reads crime stories and novels. A moron who’s killed for mistaking literature for reality. He’s the Don Quixote of detective fiction.”

Gothic realism, he believed, was the only alternative.

“Writing crime novels in this country is an act of disingenuity, doomed to fail,” he added. “Miguel, of all the cases you see every day, how many actually get solved? Who’s really going to believe that the police in this city is ever going to put a criminal away?”

Rye seemed to remember something.

“When do they take you to the Monster?” He was speaking more quietly now.

“I don’t know yet. The president himself rang the Office of Forensic Medicine to get the details of the case. You know he’s pals with Camejo Salas, right?”

“The president called Johnny Campos?”

“Uh huh. I don’t think my report will be much use anyway, whichever way it goes.”

“Campos is a rat.”

“Apparently the president’s heard about the organ trafficking thing. That’s enough to have Campos by the balls.”

“No shit.”

“Yeah.”

The lights flickered and went out. There was a wave of shouting and laughter, and then, as if muffled by the blackout, the conversations resumed in quiet conspiratorial tones. One of the waiters pulled down the shutters while Marcos, the owner, added up the checks armed with a small flashlight. Within minutes Chef Woo’s was almost empty, its dense blackness studded only by the cigarettes of the final customers, the regulars, the dependable ones.

“You’re not nervous?” asked Rye.

“Why?”

“I’d be shitting myself if I were in your shoes.”

“This stuff with the Monster in Los Palos Grandes isn’t new. It’s not even the worst thing going on now.”

“The guy kidnapped that girl, raped her and tortured her for four months. He hit her so hard it tore off her upper lip and part of an ear. You don’t think that’s a big deal?”

“What happened to Lila Hernández is horrible, we all know that. But the thing that’s really got everyone’s attention is that it was done by Camejo Salas’s boy. The son of an award-winning poet. How is that even possible? Salas won the National Prize for Literature, for Christ’s sake. And he’s the father of that freak?”

“I took classes with that asshole when I was in grad school.”

“But as for it not being the worst thing happening, how’s this for an example: One morning a guy sees two girls walking down the street. He likes what he sees and decides there and then to take them to his apartment. At gunpoint. They’re not even fifteen. He locks one in his bedroom while he rapes the second girl in the living room. The girl in the bedroom can hear the other one screaming. After a while, things go quiet—half an hour, an hour, two hours: she’s not sure. At last, hearing only silence, she manages to force open the door. But what do you think she finds in the living room? Her friend’s torso. The guy chopped her into pieces, he raped her, killed her. He’s gone out to get rid of the head and limbs. The one who’s survived goes into a panic, screaming from the window until the neighbors come rescue her.”

“Are you talking about the Casalta case?”

“San Martín.”

“Have you seen her yet?”

“Yeah.”

“And?”

“Totally lost it.”

“Maybe you won’t even get to see the guy.”

“Probably not.”

“Well, that’s something.”

“Is it? And then what, Matías? They catch the asshole, and most likely he gets finished off in prison. And then what?”

“What else do you want?”

“That’s the problem. I don’t know what you can do after that. Because there’s always something left behind. Every murder leaves a lingering trace. And that’s got to be toxic.”

“What’s the time?”

They looked around and realized they were the last customers in the restaurant. It was just them and the waiters, who were leaning on the bar, smoking, their eyes barely outlined by the glow from the cigarettes. When Matías and Miguel stood up, the four Chinese men interrupted their conversation and, for a moment, stared at the shapes they could barely discern in the darkness. Matías went to pay at the cash register while Miguel waited for somebody to open the shutters.

Once in the street, Miguel felt more relaxed. For that brief moment, he had felt an inexplicable fear. He’d suddenly pictured himself and Matías being chopped up by those same waiters who served them every week.

The street was dark and empty. There was no activity except down at the end, near the crossing. Miguel wanted to quicken their pace toward the Centro Plaza mall where he’d left his car, but Matías was in his element.

“Deprivation has its beauty. And I’m not talking about magical realism. García Márquez and the rest of them think they glimpsed it, but they didn’t. Magical realism put some blush on poverty, dressed it up, gave it wings. Gothic realism, on the other hand, finds truth and beauty in undressing, in digging things up,” said Matías.

A shape was moving among the bags of garbage piled up around a lamppost.

“See?” he said.

The tramp followed them with his vacant gaze, then carried on with his business.

“Does that look beautiful to you?” asked Miguel.

“Of course.”

“Give me García Márquez any day.”

“What’s the best entry ever to win El Nacional’s short-story prize?”

Matías Rye entered the competition every year, and every year he lost. Over time he had developed a thorough yet resentful knowledge of the prize’s history. He would name award-winning short stories and authors as metaphors for the fairness or unfairness of life.

“‘The Hand by the Wall,’ I guess.”

“No. That story was only successful because of its timing. Meneses has the dubious honor of having created a useless genre: lyrical crime fiction. The only story worth reading from that competition is ‘Anchovy.’ Humberto Mata was the first among us to understand that crime fiction is a genre with more of a past than a future.”

“I haven’t read it.”

“Read it. Once you have, every time you see a tramp, you’ll picture him living on the banks of the Guaire, waking up among herons every morning. And that’s beautiful.”

“If you say so.”

“Now, tell me. What’s the worst story to have won the prize?”

“The one by Algimiro Triana.”

“You’re only saying that because of that thing with Arlindo Falcão. Sure, Algimiro is scum, but that’s not the worst story. The title of the one I’m thinking of is impossible to pronounce. I can never remember it; I just know it’s by Pedro Álamo. It won in 1982, the prize’s most controversial year to date. The story is incomprehensible from start to finish. I’ve always taken it for the text of a madman, but some critics were determined to see a masterpiece. I think I may finally get a chance to confirm my hypothesis.”

“What hypothesis?”

“You’re going to help me. I’ve got Pedro Álamo as a student in my writing workshop.”

“What’s that got to do with me?”

“We’ve become almost friends. I gave him the number of your private practice. Can you squeeze him in next Monday? Álamo’s been having panic attacks.”

2

Origins of Symmetry

I like symmetries and detest motorbikes. Actually, I love them, and I think it’s down to some kind of fear. Symmetries, I mean. And motorbikes. I know what I’m saying. And because I know what I’m saying, I don’t need to go on about it. I don’t have to tell anyone either. If I’m talking to you, doctor, it’s only as a courtesy to Matías. He was so insistent I should come see you, especially given what happened after class, I had to promise I would. He convinced me with the fact that you’re a psychiatrist—that is, a physician, not a psychologist, a psychotherapist or a charlatan. I mean, I presume you treat your patients with medication, and I’m an advocate for the prescription and use of medication. Take depression, for instance. They say it’s the illness of the century. Depression, leaving its causes aside, is a biochemical process. Serotonin levels drop and antidepressants restore them. That’s why I say, when it comes to health matters, it’s medicine first and words after. And if words can be avoided altogether, so much the better. Since I’m convinced that all the evil in this world originates in them. In words.

That’s why I came. So you could prescribe me tranquilizers or whatever to help me erase the anxiety when it suddenly overwhelms me. Or, at least, build some kind of firewall to buy enough time to maneuver before the instant strikes, so that when I sense the motorbike approaching, I can be braced for the impact. Or run away from that damn chainsaw sound all the faster. Ever seen those Friday the 13th movies? Remember Jason? That’s what I feel like whenever I hear a motorbike coming. In fact, I don’t need to hear them anymore. Just imagining the damn sound—like a saw drawing near to cut my head off—that’s enough to make disaster unravel.

I’d like to point out, Dr. Ardiles, that Friday the 13th is only an example. I’m not traumatized by it. Freddy Krueger and Jason have always left me cold. Here in Caracas, Jason would just be a tree surgeon and Freddy some emo kid with long nails. Freddy and Jason are brats compared with the plague of motorized thugs who’ve taken over the city. Wipe them all out: that’d be the first step to truly rebuild this city. Hit them with their own helmets until they die. One by one. Margarita, a friend of mine from the workshop, told me something unbelievable the other day. She took a motorcycle taxi in Altamira to go to Paseo Las Mercedes. It was six in the afternoon, the subway system had collapsed and the buses were packed. When they were about to pull out of Chacaíto to take the main road to Las Mercedes, just opposite the McDonald’s in El Rosal, the taxi driver took advantage of a red traffic light to pull out a gun and steal a BlackBerry from the woman in the car alongside them. He didn’t wait for the light to go green. He left the cars behind and continued on his way. When they arrived at Paseo, Margarita was shaking all over. Even though she can defend herself better than your average guy, she could barely take the cash out of her purse. The driver received the fare and, seeing her so rattled, said:

“Don’t be scared, honey. I would never rob my customers.”

See what I mean, doctor? What are you supposed to do with a piece of shit like that? Huh? Excuse my language. The thing is . . . you know what I’m saying. But don’t go making assumptions either. It’s not PTSD. Despite everything, I haven’t been robbed for a while—touch wood. The thing about the motorbikes comes from before, from when I was married to Margarita. No, not the one from the story about the motorcycle taxi. Another one—my wife.

I could tell you about one particular experience that might explain it all. But I’m not going to, because I didn’t come here to talk. Let’s look at this, if you will, as a mere formality, so you can prescribe me the drugs. Because if I start talking about what happened to me back then, you’ll forget about the present, about what’s happening to me now. It’d be unfair to blame that one biker—just check out my ability for synderesis: I’m talking about being fair to such a scumbag—for all the excesses of today’s bikers. Also, it’d be impossible for them to be one and the same. It’d be too much of a coincidence. And for me, coincidences don’t exist.

Last week? Where should I start. . . . From the beginning, Aristotle would say. But where are the origins of symmetry? The thing could have started more than twenty-five years ago, or a month ago. It doesn’t matter, whatever suits you, the only thing that’d change is the direction you’re going in. You’re right, it was me who said I didn’t want to talk about the past, about the causes. Let’s start with the present then, and with the consequences, and hopefully, we’ll leave it there.

It all started, or started again, or started to take shape, when Margarita stared at me. Yes, the one in the workshop, not the one who was my wife. It was Matías’s fault. I’d sort of hoped Matías wouldn’t recognize me, that my name wouldn’t make him go back to 1982. But the morning after the first lesson, I read an email from Matías where he asked whether I was the author of “Neercseht.” I answered a simple “yes,” as if to suggest I didn’t want to talk about it. Doctor, if you want to know more, you should ask Matías. I wouldn’t recommend that you read my short story under any circumstances. I wouldn’t put anyone through that. Though there is a version of the story you might find interesting. It’s the same story but from back to front. Its title is “The Screen,” and it’s by a young writer called Rodrigo Blanco. I’ve been racking my brains but can’t think of anyone who could have shared the information with that young man. Anyhow, his story is totally misleading when it comes to my affair with Sara Calcaño. It’s true I slept with her, but it’s also true that Sara Calcaño slept with each and every one of the writers there at the time, male and female, young and old. A fact that is as true as it is useless, since Sarita ended up crazy and must be dead by now.

After the last class of December, Margarita, Matías and I stayed behind to discuss some details from “Theses on the Short Story” by Ricardo Piglia. Now I think of it, the whole thing was an ambush, with Matías playing a dirty trick on me.

“So, you are Pedro Álamo,” said Matías.

Margarita looked at him and then at me as if waiting for an explanation.

“Pedro caused one of the biggest scandals in Venezuelan literature,” he told her. “Of course, you weren’t even born yet.”

He went on to tell her all about my short story, the El Nacionalaward, the angry reaction of most critics, the incredible reaction of the few who championed my work, my stubborn silence in the following months and subsequent retreat from public life.

“Pedro Álamo was what people call—with sincere admiration but somehow bitterly—a rising star in our literature. Then he vanished. What were you up to, Pedro?”

I’d have liked to explain that all it takes to vanish from our literature, as he put it, is to avoid book launches and stop taking calls from the press. Instead, I said I’d been doing something else.

“I’m an advertising executive.”

I must confess, doctor, I enjoyed seeing the disappointment on his face. But it’s the truth: I’m an advertising executive.

“Do you still write?” Matías wouldn’t give up.

“No,” I said. “That’s why I’m here. I want to try to start afresh.”

Matías seemed unconvinced. I’m not sure myself whether what I said was true. Is it writing, this thing I’ve been doing ever since? As in, what writers usually understand by writing? I don’t know. I don’t care either. All my life I’ve been trying to play down the high hopes that, despite myself, I raise in those around me. Matías didn’t bring the subject up again, but that time, when we said goodbye, Margarita stared at me.

That night I dreamed about a noise. It sounded like a motorbike, and in the dream I didn’t know whether it was moving closer, moving away, or doing both things at once. I live in the annex of a house in the Santa Inés development. Not sure if you know the place. I’d guess not. Most Caraqueños haven’t a clue where it is, as they get it mixed up with Santa Paula, Santa Marta, Santa Fe and every other eastern santa. Meaning only the people who live there know for sure where Santa Inés is, as if Santa Inés was more than a development, it was a bond. This only happens because the place is just a handful of houses scattered in a sort of canyon that lies between the old road to Baruta and Los Samanes on one side, and the hills of Santa Rosa de Lima and San Román on the other. Santa Inés is, how can I put it, it’s a weird echo chamber. Sounds bounce around, cutting off their source on their way back, as well as the notion of what’s far away or close, like errant atoms tuning the universe.

The truth is that midway through my dream, in the dead of the night, I heard a motorbike. A humming that was gaining ground on the silence of the hour, eroding the night. That noise, the dream of the noise, seemed to go on forever. I woke at last, anxious, rolling out of bed and falling onto the floor of my room like a dead tree.

I knocked over the glass of water I always leave on the bedside table. Even though I could’ve cut myself with the shards I didn’t turn the light on. I remained on the floor like that, sitting there with a wet ass. Margarita used to hate that habit of mine. Leaving an overflowing glass on the bedside table, only to toss the water in the sink in the morning, almost untouched. I’d hardly take a sip after brushing my teeth and before turning out the light. My marriage with Margarita was a short and miserable obstacle course. Our financial situation would force us to move from one apartment to the next, from one side of the city to the other and, in every place we lived, the glass of water on the bedside table was the subject of our conversation. In the beginning, that habit of mine used to provoke a kind of affectionate confusion. But as time went by, her reaction became pure hostility. Toward the end, it was just indifference. I was very young and focused on my job in advertising after failing as a writer, and palindromes had already become an obsession. I failed to see what was evident, that things were coming to an end. Margarita would look at the glass of water on the bedside table and accept I wasn’t going to change, that I wasn’t going to give up this absurd routine or any other. That’s what Margarita would see every morning: how the fluids of our first intimacy were slowly drying, even within that glass still filled with water.

I was still on the floor, mind wandering, but one last feeling finally woke me up. The distant sound of the dream reverberated in my ears. The motorbike could easily now be a small plane disappearing into the horizon. And the slow fading of the sound was so subtle it became indistinguishable from the collapse of the night. I looked around before getting up. The small puddle of water and the bits of glass made me think about global warming and melting ice caps. I couldn’t help but notice that the puddle was pulsating, and I kept thinking about it for the rest of the day.

Time flies.

Sorry to have taken up your time, and thank you. I really appreciate the prescription and the Xanax.

Yeah, sure, anything you like.

Don’t worry, honestly, go ahead.

Margarita? My wife?

Oh, she died years ago. Killed, poor thing.

3

Gothic City

Matías had been avoiding me all week. He didn’t answer my emails—although he did forward me a few threads with updates on the blackouts and the state of the power stations. He also sent me, in an email without a subject or a signature or any comment, an article about the bodies of women found in the wastelands of Parque Caiza. He behaved similarly on the phone. He was always just about to go into a movie theater or attend a meeting. He didn’t want me to let on until Friday. He didn’t say as much, but it’s obvious, I know what he’s like. Pointless, as I wouldn’t have told him anything anyway. Not only because Pedro Álamo never talked about his famous short story, but because it wouldn’t be right for me to gossip about the private lives of my patients.

“That’s nonsense.” Matías seemed annoyed. “You always tell me about the cases you see in Forensic Medicine.”

“That’s different. A lot of those stories end up in the papers anyway.”

“But that’s even worse. You’re breaking a gagging order.”

“You’re right. I won’t tell you about those cases anymore.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Álamo hasn’t even mentioned his short story. Trust me, the story is the last thing he wants to talk about. And if he’d said something, I still wouldn’t tell you. It wouldn’t be ethical.”

Then I thought about the voice recorder. My habit of recording and transcribing the sessions with some of my patients. “Atoms,” “Universe,” “The collapse of the night,” “Global warming,” “Icecaps.” What would I call what I was doing? Definitely not ethical, that’s for sure.

I felt more relaxed after the first beer.

“At first sight, he seems the obsessive-compulsive type.”

“Why would you say that?” said Matías, his face hardening.

“And with paranoid tendencies. And some idées fixes. Especially about motorbikes, but also about his wife, this Margarita who was killed years ago.”

“There’s a girl in the workshop called Margarita. Apart from me, she’s the only one he talks to.”

“There you go.”

I changed the subject. I asked him about the book.

“The Night.” He liked saying the book’s title aloud before talking about it. Maybe because it’s a great title. Maybe because it’s been a while since Matías wrote anything but titles. “I’m still taking notes and working on a rough draft. I think I’ve figured out the main character. A psychiatrist who rapes and kills his patients. Only women. It’s based on Dr. Montesinos, obviously: the national psychiatrist, go-to intellectual, president of the Central University, former national presidential candidate.”

I thought about Camejo Salas. I tried, without much luck, to remember some of the verses I’d been made to memorize in school.

The lights flickered at Chef Woo’s.

“We’ve been raised by murderers.”

I hadn’t meant to say that. I was just thinking about it and said it without realizing.

“What if one day we found out our parents were murderers. Can you imagine, Matías?”

“At this rate, we’ll wake up one day to discover we’re murderers ourselves,” said Matías. “And lighten up. You can be such a bore sometimes. You should retire. How long have you got left?”

“Five years.”

Now it was Matías who changed the subject. He wanted me to go over the case of Dr. Montesinos again, giving him chapter and verse. He took out his Moleskine notepad, as he did whenever he wanted me to tell a story.

I told him what I knew about the Montesinos case.

“I need to know everything about psychiatrists.”

“Go on.”

“Facts, habits, routine, jargon. That kind of thing.”

“Let’s see. Forty percent of male psychiatrists in Venezuela are homosexual.”

“And what do you expect me to do with that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why are you telling me, then?”

“You asked for facts. That’s a fact.”

“Forty percent?”

“Maybe fifty, I don’t know.”

“How do you know?”

“I can work it out from the cases I know. A few are quite open about it. But most of them are married men with children.”

Matías went quiet. I thought he was finally going to ask me what he had always wanted to ask me. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved