EDEN

1

EVERY YEAR, IN those last hazy summer days before school begins, the students of Atwood go into the woods to cheat death. It’s a tradition as old as the school, observed in the strange, liminal week after students begin to arrive but before classes start. We make our way down in twos and threes and fours, some laughing and chattering, some silent with simmering nerves. Not everyone jumps, but everyone knows who doesn’t.

The four of us always jump. Veronica, Zoya, Ruth, and I. Even when we weren’t supposed to—Lower School students aren’t allowed, but in that first year, Veronica and I sneaked out on our own to fling ourselves over the Narrow.

It’s our senior year now. Our last chance to leap. And I’ve almost missed it.

I’m barely out of the taxi that brought me from the airport when Veronica comes striding across the campus lawn toward me, arms outflung. Her white-blond hair is long on the top and shaved on the sides, which accentuates the sharp angles of her face. She wears a loose white tank that shows off the black sports bra beneath, accessorized with a collection of silver pendants and bracelets. On me, the look would be Witchy Nervous Breakdown, but on her it’s pure glamour.

“Thank the goddess you made it! You almost missed the leap,” she declares, and I stretch a grin across my face to mirror hers. The cut on my lip has sealed itself to a whisper. The bruise at my lower back is a faint yellow, barely noticeable, but I tug down my shirt anyway. I keep my left hand in my sweatshirt pocket, and as long as I don’t jostle it, my arm doesn’t hurt.

“I thought about joining the circus instead, but then I remembered there are plenty of clowns here,” I tell her. I practiced the joke on the way here, terrible as it was. Fine-tuned it, orchestrating just the right facial expression and tone of voice. I shouldn’t have bothered. Veronica is my favorite person in the world, but she isn’t exactly observant.

“It’s supposed to rain later, so we’d better get moving if we want to get it done before classes start,” Veronica says, jerking a thumb over her shoulder. Halfway across the lawn, Ruth and Zoya stand together in a pose of expectant waiting. Ruth raises a hand to wave.

“You go on,” I tell Veronica. “I’ve got to get my stuff to my room.” All the way here, I’ve had a knot in my stomach. I’m not ready to face Veronica—or anyone. I can’t explain what happened a week ago—or what was happening all summer while she swanned around Tuscany and sent texts complaining about how much her parents were smothering her.

“Don’t be ridiculous. You can leave it here. It’s not like anyone’s going to steal it,” she says with a wrinkled-up nose. “Come on. It’s senior year. We can’t not jump.”

The taxi driver has finished unloading my suitcases from the trunk. I take a deep breath. I’m here. I’ve made it to Atwood. All summer, I told myself I just needed to get back here, and everything would be okay.

And it is okay.

I’m okay.

“Help me drag my stuff up on the sidewalk, at least?” I say brightly.

Veronica groans at the prospect of physical labor but obliges. She practically flings my roller bag onto the grass. I move more cautiously, forced to pick up each bag one-handed, still aware of the random aches and pains that ambush me when I move the wrong way. I’ve barely set the last bag down when Veronica seizes my hand and starts

dragging me toward the woods.

“It’s been so boring without you, Eden. Just me and these losers.”

“I resemble that remark,” Ruth says. Zoya just offers a tiny finger-wave.

The two of them are a study in opposites, and it isn’t just because Zoya is almost six feet tall and the approximate width of an electron while Ruth is five-three and looks like she could flip a steer by its horns. Zoya looks immaculate as always, wearing a boldly printed top and fitted trousers she made herself under a tunic-length cardigan. She and Veronica are the fashion icons of the group. Meanwhile, when Ruth isn’t in her school uniform, she’s usually dressed like she is now, in running shorts and a tank, and according to Veronica, I have the fashion instincts of a nineteenth-century governess, tragically orphaned and tasked with caring for two polite but unsettling British children.

“Why’d you show so late? You’re usually the first one here,” Veronica says.

“I had some stuff to deal with at home,” I say. I paid to have my ticket changed to give the bruises time to heal.

“Everything all right?” Zoya asks softly.

I don’t quite meet her eyes as I shrug. “I’m here now.” The rest of the world doesn’t need to exist, at least for a few months.

“That’s right. You’re finally here, and we can finally jump,” Veronica says with pleasure.

“Say that a little louder, won’t you?” Ruth says, rolling her eyes.

“You mean I shouldn’t talk about how WE’RE GOING TO JUMP THE NARROW?” Veronica shouts. A few people glance toward us, including Mr. Lloyd, our English teacher, but there are no answering shouts of alarm or any rush to clap us in irons. Technically, jumping the Narrow is forbidden, and the teachers are supposed to stop you if they catch you, but they never try to catch you. Most of them did it, too, back in the day.

“Could you please . . . not?” Zoya says with a little burr of irritation. If she and Ruth are opposites, she and Veronica sometimes clash because they’re too similar. Both tall and willowy, the kind of build you could drape a potato sack over and call it high fashion—not that they ever would, since both of them have a keen fashion sense and the bank accounts to indulge it. Veronica is white, and Zoya is Black, but they even have similar bone structure, with sharp chins and big eyes. But Veronica is all brash energy and charisma, and most of the time Zoya seems like she wants to fold in on herself and disappear.

“Sorry,” Veronica says

with a toss of her hair, unconcerned.

We start off together, Ruth taking the lead despite her short stature, thanks to her business-like stride, Veronica and me in the middle, and Zoya drifting just behind us.

The only way down to the Narrow is through a gap in the fence behind the old chapel. In my six years at the school, it’s never been fixed.

“Aren’t the boys coming?” I ask, glancing around for a sign of Diego or Remi—Ruth’s and Veronica’s boyfriends, respectively.

“No boys allowed. Just the four of us, one last time.” Veronica throws an arm over my shoulder.

One last year at Atwood, away from the world.

“Are you okay?” Veronica asks. She’s looking down at me with a quizzical expression, and a lie springs to my lips—yes, of course I’m okay. Why wouldn’t I be?

I’ve been lying to Veronica since the first day I arrived at Atwood. There’s no reason to stop now. My tongue nudges the lingering seam where my lip split, and I look away. “I don’t know. It doesn’t feel like I’m here yet.”

“That’s because you haven’t jumped. The real world doesn’t go away until you jump,” Veronica says confidently. And then we’re at the back of the chapel, and we have to break apart to walk single file down the path. We pick our way along in relative silence.

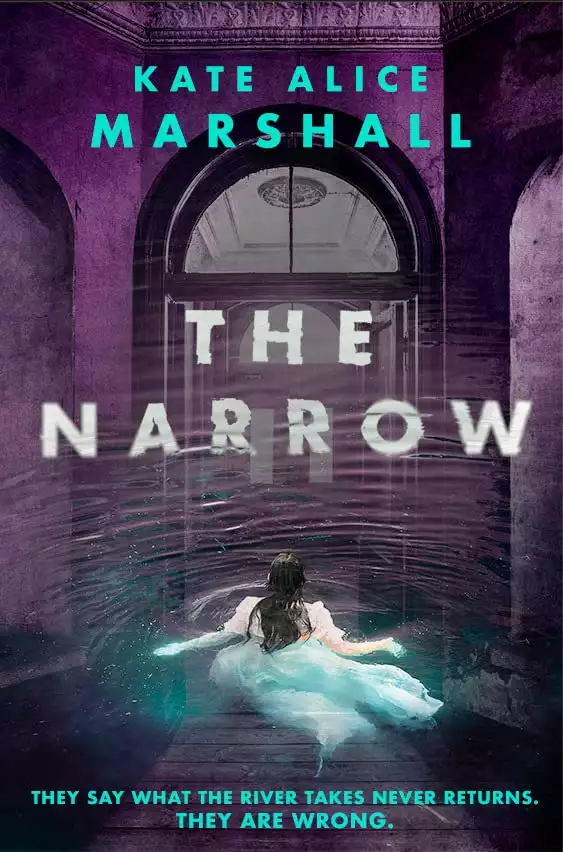

We hear it before we see it. For the deadliest body of water in the county, the Narrow doesn’t sound very threatening—no crash and rush of rapids or waterfalls, just a cheerful babble that suggests a friendly forest creek. At first glance, that’s all the Narrow is: a thin ribbon of water flowing amid moss-covered rocks beneath a swaying canopy of branches, the banks little more than one long stride apart. But appearances can be deceiving.

Only half a mile up, the little babbling brook is a river, wide and shallow. Then its banks tighten. Through some quirk of geology, they cleave together, forcing all that water through a channel only a few feet wide. Over the years, the river has carved a path not out to the sides but straight down. Essentially, the river turns on its side, running narrow, deep, and fast. So fast that it snatches anything or anyone unfortunate enough to fall into the water, and no matter how hard you struggle or how fast you swim, there is no way to fight the pull.

Legend says that no one who’s ever fallen into the Narrow has survived. Not only that, but the currents and the pockets and caves in the rock mean that any bodies will likely get trapped, never to emerge. No one who ever goes in comes out again. Or so they say.

Veronica and I know better.

By tacitly letting us get away with the jump, the staff can encourage certain limits. You only jump during daylight when the ground is completely dry, and only at the one small section where the boulders overhanging the water shrink the gap to a manageable four feet. Lower School students—sixth, seventh, and eighth graders—aren’t allowed, and there has to be someone on the other side to grab you if you slip. Officially, no student has fallen into the Narrow in forty years.

By the time we reach the river, there’s a crowd gathered. Other students, like us, trying to get their jump in before the rain starts. You can’t jump after the first day of classes. It doesn’t count.

A little knot of Lower School students clusters along the near shore. A couple of them are already wearing uniforms. A gangly boy in a He-Man T-shirt is bouncing up and down on the balls of his feet, arms swinging as he psychs himself up. I don’t recognize him, so I assume he’s a freshman—that is, in his first year at the Upper School. Lower School students are either collectively known as Littles or just by grade level. The Upper School is much larger than the Lower School. Not a lot of parents think it’s a good idea to ship their eleven-year-olds off to the middle of the woods to learn Latin. Ruth, Veronica, and I are all lifers, as Lower School veterans are called, but Zoya enrolled when she started high school.

“Hurry it up!” Ruth hollers, clapping. “You can do it! Don’t think, just leap!”

“Ten bucks says he can’t,” Veronica calls loudly, and the boy flashes her a panicked look. She folds her arms, one eyebrow raised.

“She’s really very nice once you get to know her,” I promise him, and Veronica snorts.

The boy gives one last full-body shake, sets his feet, and dashes across the rocks. They’re coated with shaggy green moss. Even a whisper of rain could make them treacherously slick, but dry, they provide plenty of traction as he takes three long strides and flings himself across the four-foot gap. He clears it easily, and the crowd on the other side catches hold of him, dragging him in for back slapping, hooting, and hollering.

“My turn!” Ruth yells, and charges forward.

“Go for it, Hwang!” someone yells, but by the time they get out the last syllable, it’s already old news. She’s on the other side, brushing imaginary lint off her shoulder.

“Let’s get this over

with,” Zoya says, her faint Russian accent sharpening the th. She’s so tall, she can practically just step over the gap, but she does it in an elegant hop. On the other side, awed freshmen scatter, gawking up at her. She wraps her cardigan tight around herself and stalks over to Ruth.

“Together?” Veronica asks, putting out her right hand for me to take.

Her hand hovers in the air. My left hand stays wedged in my pocket, my forearm pulsing with dull pain. We always jump together since that first illicit mission down to the water. “You go ahead,” I find myself saying.

A frown tugs at the corners of her mouth. But then she wheels around, and with a whoop, she runs. She jumps. She lands in an ungainly crouch on the other side, wheezing laughter like a hyena, and bounces to her feet to beckon me.

“Your turn!” she calls.

I’m the last Upper School student on the near side. A group of jumpers are heading upstream, toward the bridge half a mile away. That’s another rule: you only jump once. Jumping back is tempting fate. For the Narrow is greedy and lonely and cruel.

We jump to defy it. We jump to feel alive and free. We jump because the real world can’t follow us across the cold water.

Ruth calls my name. Veronica stares at me, expression unreadable. I’ve been standing still too long. Gingerly, I take my hand from my pocket, gritting my teeth against the zips of pain that follow. I force myself into motion, running up the gentle slope of the big boulder that hangs out over the water. Dozens of feet have churned up the shaggy moss, tearing at it with every step, leaving small slick patches of brown. I plant my foot at the edge of the rock to leap.

Mud shifts beneath the sole of my foot, twisting my heel maybe half an inch to the left. I push off.

I’m in the air, but my balance is off. I hit the other side. My foot shoots out from under me. I pitch back toward the water. Someone in the crowd screams—

And Veronica catches my right arm. She pulls, and I stumble forward into her arms. Into Atwood’s embrace.

“You made it,” she says, eyes gleaming with pleasure.

Finally it feels true. I’m here. I’m home.

Everything is going to be all right.

2

“HOLY CRAP, EDEN, you almost died,” Ruth admonishes me.

The raw panic of the moment lingers, a tightness in my throat and on my skin, but it’s fading fast. I crack a smile. “I didn’t almost die. I almost landed on my butt in front of a bunch of Lower School students, permanently damaging my air of cool. Which, if you think about it, is worse,” I say, each laughing word a brick in the wall between me and that instant of gut-churning fear.

“If you had died, you would be a legend,” Zoya points out. Everyone is flaking off toward the bridge now, us included.

“It would have been really impressive if you managed to fall in when no one else ever has,” Ruth agrees, walking backward so she can smirk at me.

“People have fallen in,” I object.

“Tourists,” Ruth says dismissively.

“Not just tourists. There was that guy from town a few years ago,” Zoya says.

“And the Drowning Girl,” Veronica says. Ruth makes ghost noises; Veronica rolls her eyes. “Just because you’re a boring skeptic doesn’t mean you get to make fun of the rest of us.”

“I’m not making fun. I find your mysticism endearing,” Ruth assures her. “I hate that story, though. It’s so . . . unfeminist.”

“I think it’s romantic,” Veronica protests.

“Throwing yourself into a river because your boyfriend stood you up isn’t romantic, it’s idiotic,” Zoya says.

“What do you think, Eden?” Veronica asks, but I’m distracted as we pass a group of girls whispering to each other. I catch the name Aubrey and Did you hear what happened? before we’re out of earshot. I glance back with a frown, but Veronica links her arm in mine, and I don’t slow down.

The legend of the Narrow is probably exaggerated, but enough people drown—one or two every decade or so—to make it clear it isn’t all talk. And it’s true that, often, the bodies are never found. A few corpses do wash up downstream or near town where the river empties into the Atlantic, though that doesn’t make as good a story.

And it isn’t true that no one has ever survived falling in. But we never talk about what happened that first night we made the jump.

“White! Hey, Eden White!” a voice calls just as we’re nearing the path back up to campus. It’s a sophomore girl I vaguely recognize—Martha or Mary or something old-fashioned. She’s picking her way along the edge of the trail, dodging bodies. When she spots me, she stops, planting a foot on a tree root. “Oster wants to see you,” she informs me, a tad breathlessly.

Geoffrey Oster is Atwood’s dean. I’ve spoken to him maybe three times in the last six years. As much as it is possible to blend in at a school with fifty students to a class, I do. I’m not an Instagram star like Zoya or an artistic prodigy like Veronica or a future Olympian like Ruth. I’m not like most of the Atwood students—I didn’t come here because of long family tradition, for the access to influence, the leg up on getting into the Ivies. I came because it was a matter of survival.

I can’t imagine what Geoffrey Oster wants with me.

“You’ve been back for like ten minutes, and you’re already in trouble?” Veronica says lightly.

“He wants to see you

immediately,” maybe-Martha says, and I shift uneasily.

“We’ll see you at the room?” Zoya suggests.

“Yeah. I’ll meet you there when I’m done,” I say, feigning a lack of concern.

Could Oster know about what happened this summer? The only people who could have told him are my parents, and there’s no way they would.

The dean’s office is in the main administration building, a piece of neoclassical architecture utterly devoid of imagination. A few white columns stand in a plodding row and a clumsy frieze depicts an unspecified scholar above the main entry. Inside, things are tidy and functional, with stately wood paneling enlivened with modern art on the walls.

The door to Oster’s office is open, the man himself standing in front of his desk with his back to me. He holds his glasses in one hand and is staring at nothing in particular. I knock on the doorframe.

“Miss White,” he says in acknowledgment, turning. “Good. Please come in, will you? And shut the door behind you.”

I obey, and Oster moves around to sit behind his desk. I take a seat, memories of the last time I sat in this room echoing in my mind.

It would only be for one night. I have a very important meeting in the morning that I absolutely cannot miss.

I’ve barely sat down when there’s a knock at the door behind me, and gray-haired Edith Clarke enters, a manila folder in one hand. I catch a glimpse of the letters whi on the tab, the rest of my name hidden under her hand.

“Edith, thank you for joining us,” Oster says. He puts his glasses on, and I resist the urge to fidget. He’s a big man, with short white hair and lively eyes. He was the youngest dean in Atwood’s history when he was hired, but that was nearly forty years ago, and now his face is lined with deep wrinkles, his scalp flecked with liver spots. I don’t know much about him other than the fact that he’s friends with Veronica’s parents.

“Am I in some kind of trouble?” I ask.

“Should you be?” he asks in turn, brows lifted.

“I know a trap when I hear one,” I reply, and he chuckles. But honestly, I can’t think of anything. Sure, I break a few rules here and there. But I’ve never done anything that required being summoned in front of the dean.

Mrs. Clarke has adjusted the other chair so she’s sitting off to the side. Suddenly, the significance of her presence hits me. Edith Clarke is the bursar—in charge of tuition and financial aid. I’ve never had to talk to her myself, but Ruth is on partial scholarship, and I’ve walked with her to Clarke’s office a few times over the years when she had to drop off a form or something.

“Miss White, I’m afraid we have a situation regarding your enrollment,” Oster says,

drawing my attention back to him. His hands are neatly folded on the tabletop. I find myself staring at the hair on the back of his fingers. “Tuition must be paid in full before the first day of classes. Yours has not been paid, and despite repeated attempts, we have been unable to get in touch with your parents.”

My heart drops, and a sour taste floods my mouth. “It hasn’t been paid? At all?”

“I’m afraid not.”

I’m afraid, I’m afraid. He keeps saying that, but he isn’t afraid, is he? Sympathetic, yes. His voice is syrupy with that. But the fear here—it belongs to me. “What does that mean? What happens now?” I ask.

“My hope is that you can put us in touch with your parents,” Oster says. “I’m sure it’s just a misunderstanding.”

“Our policies are quite clear,” Mrs. Clarke adds. “If your tuition is not paid, you are not an enrolled student and you cannot stay in the dorms or attend classes.”

Oster looks at her sharply, but I’m grateful to her for just spelling it out. They’re saying I can’t stay here. I have to go home.

And I can’t go home.

“Miss White—Eden. If your family is experiencing some kind of financial hardship—”

I laugh. It’s a horrible, choked sound, and it makes them both wince. “No, we aren’t experiencing financial hardship,” I say. Though if you asked my parents, they might disagree.

Every few months someone posts a rich guy’s monthly budget to “prove” that they’re barely getting by, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved