- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

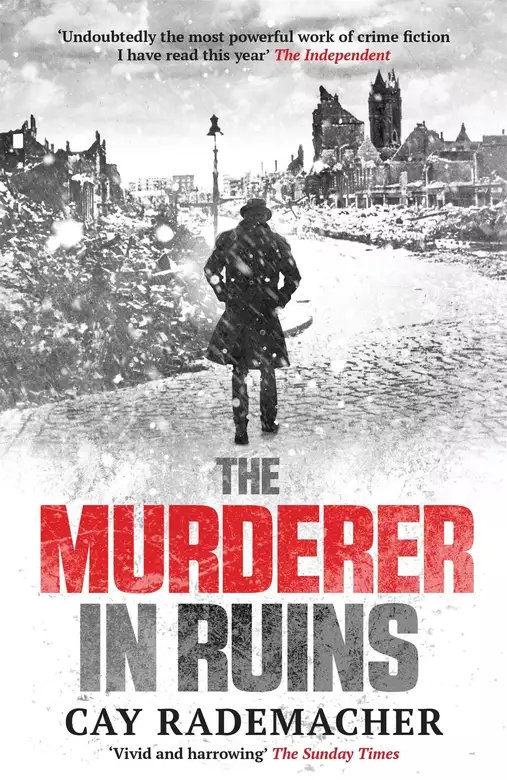

SHORTLISTED FOR THE CWA INTERNATIONAL DAGGER AWARD 2016 Hamburg, 1947. A ruined city occupied by the British who bombed it, experiencing the coldest winter in living memory. Food and supplies are rationed; refugees and the homeless are crammed into concrete bunkers and ramshackle huts; trade on the black market is rife. A killer is on the loose, and all attempts to find him or her have failed. Plagued with worry about his missing son, Frank Stave is a career policeman with a tragedy in his past that is driving his determination to find the killer. With frustration and anger mounting in an already tense city, Stave is under increasing pressure to find out why - in the wake of a wave of atrocity, the grim Nazi past and the bleak attempts by his German countrymen to recreate a country from the apocalypse - someone still has the stomach for murder. The first of a trilogy, The Murderer in Ruins vividly describes a poignant moment in British-German history, with a riveting plot that culminates in a shocking denouement.

Release date: August 15, 2015

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 334

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Murderer in Ruins

Cay Rademacher

Still half asleep, Chief Inspector Frank Stave reached an arm out across the bed towards his wife, then remembered that she had burned to death in a fire storm three and a half years ago. He balled his hand into a fist, hurled back the blanket and let the ice-cold air banish the last shades of his nightmare.

A grey dawn light filtered through the threadbare damask curtains he had salvaged from the rubble of the house next door. For the last five weeks he had secured them to the window frames every evening with a few drawing pins he got hold of on the black market. The windowpanes were as thin as newspaper and even encrusted with ice on the inside. Stave was afraid that one of these days the glass would crack under the weight of the ice. Even the thought was absurd: these windows had been shaken by the shock waves from countless exploding bombs without shattering.

The blanket was frozen against the wall in places. In the dim early morning light the layer of hoar frost on the walls was so thick they looked as if they were covered with a layer of calloused skin. All that remained underneath was a few strips of wallpaper that might have been fashionable in 1930, stained plaster and in places just the bare wall itself: black and red brickwork and pale grey mortar.

Slowly, Stave made his way to the tiny kitchen, its icy floor tiles freezing the soles of his feet despite two pairs of old socks. With stiff fingers he groped around in the little counter-top wood-burner until at last he got a fire glowing in its tiny barrel-shaped belly. There was a stench of burning furniture polish because the wood he had been feeding into it used to be a dark chest of drawers from the bedroom of the house next door which was hit by a bomb back in the summer of 1943.

Not just a bomb, the bomb, Stave thought to himself. The bomb that took his wife from him.

While he waited for the block of ice in the old Wehrmacht kettle on top of the stove to melt and at the same time bring a little warmth into the apartment, he pulled off the old wool pullover, the police tracksuit, two vests and the socks in which he had slept. Carefully, he set them down on the rickety chair next to his bed. With an allowance of just 1.95 kilowatts of electricity a month – precious energy reserved for the hotplate and his evening meal – he didn’t switch on the light; he had taken care, as always, to lay out his clothes in the same order, so that he could put them on in the gloom.

Stave splashed glacial water on his face and body, the drops burning his skin, causing him to shiver involuntarily. Then he put on his shirt, suit, overcoat and shoes. He shaved slowly, carefully, in the half-light; he had no way of making lather and his razor blade was dull. New ones wouldn’t be available on the ration coupons for a few weeks yet, if at all. He let the rest of the water continue to warm up on the stove.

Stave would have liked freshly ground coffee, like he used to drink before the war. But all he had was ersatz coffee, a powder that produced a pale, grey brew when he poured the lukewarm water on it. He stirred in a spoonful of ground acorn roasted a few days previously, so that it at least had a bitter taste. Add a couple of slices of dry crumbling bread. Breakfast.

Stave had traded in his last real coffee at the railway station yesterday, in exchange for a few crumbs of worthless information. He is a chief inspector of police, a rank introduced by the British occupation forces, and one that to Stave, who grew up with terms such as ‘Criminal Inspector’ or ‘Master of the Watch’, still sounds odd.

Last Saturday he arrested two murderers. Refugees from East Prussia, who’d got involved with the black market and had strangled a woman who owed them something and thrown her body into a canal, weighted down with lump of concrete from one of the ruins. They’d gone to the trouble of hacking a hole in the half-metre thick ice to dispose of their victim. It was their bad luck that they had no knowledge of the local tides, and when the water went out their victim lay there for all to see, lying in the sludge beneath the ice, as though under a magnifying glass.

Stave quickly identified the victim, found out who she had last been seen with, and arrested the killers within 24 hours of her death.

Then, as he did every weekend when he was not overwhelmed with work, he went down to the main railway station and mingled with the endless streams of people on the platforms and asked around amongst all the residents of Hamburg who had been on foraging trips in the surrounding countryside and all the soldiers still retiring home: asked them in a hesitant, whispering voice, if they might have heard anything of a certain Karl Stave.

Karl, the boy who in 1945, at the age of 17, had signed up as a schoolboy volunteer in a unit bound for the Eastern Front, which by then already ran through the suburbs of Berlin. Karl, who had lost his mother, despised his father as ‘soft’ and ‘un-German’. Karl, who since the battle for the capital of the Reich had been missing, become a phantom in the no-man’s-land between life and death, maybe fallen in battle, maybe taken by the Red Army as a prisoner-of-war, maybe on the run somewhere and using a false name. But if that had been the case, would he not, despite all their disagreements, have got in touch with his father?

Stave wandered around, spoke to emaciated figures in greatcoats far too big for them, men with the ‘Russia face’. He showed them a grimy photo of his boy and was rewarded only by shaking heads, tired shrugs. Then, finally, someone who claimed to know something. Stave gave him the last of his coffee, and was told that there was a Karl Stave in Vorkuta, in a prisoner-of-war camp, or at least somebody who might once have looked like the boy in the photograph and whose name was Karl, maybe, and who was still behind bars there, maybe. Or maybe not.

Suddenly three knocks on the door jolted him out of his thoughts; to save a few milliwatts of power the chief inspector had pulled the fuse from the electric doorbell, For a split second he had the absurd hope it might be Karl, knocking on his door at this hour of the morning. Then Stave pulled himself together: don’t start imagining things, he told himself.

Stave was in his early forties, lean, with grey-blue eyes, short blond hair with just the first hints of grey. He hurried over to the door. His left leg hurt, like it always did in winter. His ankle had been stiff ever since he was injured on that night, back in 1943. Stave had a slight limp as a result, but was in denial of his handicap to the extent that he forced himself to jog, to do stretching exercises and even – at least when the Schulzes downstairs were not at home – rope-skipping.

In the doorway stood a uniformed policeman, wearing the high cylindrical Shako helmet. That was all Stave could make out at first. The stairwell had been dark, ever since somebody stole all the light bulbs. The policeman must have had to feel his way up the four flights of stairs.

‘Good morning, Chief Inspector,’ he said. His voice sounded young, trembling with nervous excitement. ‘We’ve found a body. You need to come right away.’

‘Fine,’ Stave answered, mechanically, before it hit him that the word was hardly appropriate in the circumstances.

Had he no feelings left? In the last years of the war he had seen far too many dead bodies – including that of his own wife – for news of a murdered human being to shock him. Did he feel excitement? Yes, the excitement of a hunter spotting a wild animal’s tracks.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked the young policeman, pulling on his heavy wool overcoat and reaching for his hat.

‘Ruge, Police Constable Heinrich Ruge.’

Stave glanced at his blue uniform, the metal service badge with his number on the left side of his chest. Another innovation by the British who hated all German policemen: a four-figure number worn over the heart, a glittering target for any criminal with a gun. The overcoat was much too big for this policeman, who was skinny and young, scarcely older than Stave’s son.

When the British occupation force had taken over in May 1945, they had sacked hundreds of policemen – anyone who had been in the Gestapo, anyone who’d been in a position of power, anyone who’d been politically active. People like Stave, who under the old regime had been considered ‘on the left’ and been relegated to low-ranking unimportant jobs, were kept on. New people were brought in, boys like this Ruge, too young to know anything about life, let alone anything about police work. They were given eight weeks’ training, a uniform and then sent out on to the street. These rookies had to learn on the job what it meant to be a policeman. They included poseurs, who were no sooner in uniform than they were snapping orders at their fellow citizens and striding through the ruins like members of the Prussian nobility. Shady characters too, the sort you’d have seen in police stations back in the days of the Kaiser and the Weimar Republic, except that then they were in the cells, not behind a desk.

‘Cigarette?’ Stave offered.

Ruge hesitated a second, then reached out and took the Lucky Strike. Smart enough not to ask where the chief inspector got an American cigarette.

‘You’ll have to light it yourself,’ Stave added, apologetically. ‘I’ve hardly any matches left.’

Ruge put the cigarette in his uniform pocket. Stave wondered if the lad would smoke it later or keep it to exchange for something else. What? He pulled himself together: he was starting to suspect the motives of everyone he met.

Ready at last, he turned towards the door, then reached for his shoulder holster. The boy in uniform stared and watched as Stave fastened the leather belt around him, with the FN 22, 7.65mm calibre pistol in it. Uniformed police carried 40cm truncheons on their belts, no firearms. The British had confiscated them all, even air rifles from funfairs. Only a select few in the serious crime department were allowed to carry guns.

Ruge seemed to be getting more nervous still. Maybe he had just realised that this was serious. Or maybe he’d just like a gun himself. Stave dismissed the thought.

‘Let’s go,’ he said, feeling his way out into the dark stairwell. ‘Watch out for the steps. I don’t want you falling down them and leaving me with another corpse to deal with.’

The two men plodded downstairs. At one point Stave heard the young policeman curse quietly, but couldn’t be sure if he had missed a step or stubbed his toe on something. Stave knew every creaking step and could make his way down even in total darkness by the feel of the banisters.

They emerged from the building. Stave’s room was at the front, on the right on the top floor of the four-storey rental block in Ahrensburger Strasse: an art nouveau building, the walls painted white and pale lilac, although that was hardly obvious under the layers of dirt and grime; an ornamented façade, tall, white windows, each apartment with a balcony, a curved stone balustrade with wrought iron. Not a bad building at all. The next but one was similar, only with brighter paint. The one that used to be in-between was similar too, but all that remained was a couple of walls and heaps of bricks and rubble, charred beams, a stove pipe so tightly wedged into the ruins that no looter had managed to steal it yet.

That used to be Stave’s house. He lived there, at number 91, for ten years until that night, the night the bombs fell and took the houses down with them: one here, one there. Leaving holes in rows of houses along the city’s streets like missing teeth in a neglected mouth.

Why number 91, but not number 93 or number 89? There was no point in asking the question. And yet, every time he left the building where he now lived, Stave thought about it. Just as he thought back to pulling his wife’s body out from under the rubble, or rather pulling out what remained of her body. A while later, somebody – he couldn’t remember who now, he could hardly remember much at all from those weeks in the summer of 1943 – had offered him the flat in number 93. What had happened to the people who had previously lived there? Stave had forced himself not to ask that question either.

‘Chief Inspector. Sir?’

Ruge’s voice seemed to come from miles away. Then a surprise: there was a police car standing in front of him, one of just five functioning vehicles at the disposal of the Hamburg Police Department.

‘Now that’s what I call luxury,’ he mumbled.

Ruge nodded. ‘We need to hurry up before anyone gets wind of what’s up.’ He sounded particularly proud of himself, Stave thought.

Then he threw open the door of the 1939 Mercedes Benz. Ruge had made no move to open it for him. Instead he went round the box-like vehicle and climbed into the driver’s seat.

He put his foot down, driving in a zigzag. Before the war Ahrensburger Strasse had been dead straight with four lanes, almost too wide, the houses on either side not quite big enough for such a grand boulevard. But now there were ruins in the road, house façades lying like dead soldiers who’d fallen on their faces, chimneys, indefinable heaps of rubble, bomb craters, potholes, tank tracks, two or three wrecked cars.

Ruge swerved round the obstacles, too fast for Stave’s liking. But the boy was excited. The street lights, those that were still standing, no longer worked. The sky hung low above them; an icy north wind blowing down Ahrensburger Strasse. There had to be a crack in the old Daimler’s rear windscreen, letting Siberian air into the car. Stave pulled his collar up, shivering. When was the last time he’d felt warm?

The headlights swept over the brown rubble. Despite the early hour and a temperature of minus 20°C, a few people were already wandering like zombies along either side of the street: gaunt men in dyed Wehrmacht greatcoats, skeletal figures with one leg wrapped in rags, women with wool scarves wrapped around their heads, covering their faces, laden down with baskets and tin cans. More women than men, many more.

Stave wondered where they were all going so early. The shops were only open between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. in order to save electricity for lighting, and that’s if they had anything to offer on the rations.

There were still nearly one and a half million people in Hamburg. Hundreds of thousands had died in the fighting or in the bombings; many more were evacuated to the countryside. But their place had been taken by refugees, and DPs, Displaced Persons, liberated concentration-camp inmates and prisoners-of-war, most of them Russians, Poles, Jews who either couldn’t go back home or didn’t want to. Officially they lived in the camps the British provided for them, but many of them preferred to struggle along in the devastated metropolis on the banks of the Elbe.

Stave looked out of the window and saw the jagged remains of a house, just walls, like those of some mediaeval ruin, only thinner. Behind them more walls, and then more, and yet more. It’ll take centuries to rebuild, he thought to himself. Then he jumped, startled.

‘One Peter, One Peter’. The Hamburg police call sign these days.1 A tinny voice, but louder than the groaning eight-cylinder engine. The radio.

For the past year the British had allowed the police to use the old Telefunken boxes to transmit from their headquarters in the Stadthaus. However, the five radio-patrol cars could only receive and not send messages – none of them had a transmitter on board – so the people at headquarters had no idea if the messages got to them.

‘One Peter,’ the tinny voice continued. ‘Please report in when you reach location.’

‘Bloody bureaucrats,’ Stave muttered. ‘We’re going to have to find a telephone when we get there. Where are we heading anyway?’

Ruge braked; a British jeep was coming towards them. He pulled to the side, letting it pass, acknowledging the soldier at the wheel, who ignored him and drove straight past leaving a cloud of dust in the dry air.

‘Baustrasse, in Eilbek,’ the uniform answered. ‘It’s…’

‘…near Landwehr railway station. I know it.’ Stave’s mood was darkening. ‘There’s not a single house still standing in Eilbek. What are those idiots thinking? How do they expect us to report in? By carrier pigeon?’

Ruge cleared his throat. ‘I regret to inform you, Chief Inspector, that we will not even be able to drive as far as Baustrasse.’

‘We won’t?’

‘Too much rubble. We’ll have to walk the last few hundred metres.’

‘Great,’ Stave muttered. ‘Let’s hope we don’t tread on an unexploded bomb.’

‘There have been lots of people hanging round the scene of the crime of late. There’s nothing left to blow up there.’

‘The scene of the crime?’

Ruge blushed. ‘Where the body was found.’

‘So, you mean the location of the body,’ Stave corrected him, but trying to do so as gently as possible. All of a sudden he felt his mood lightening, forgetting the cold and the rubble and the ghostly figures drifting along the side of the road. ‘Do you have any idea what we can expect to find?’

The young policeman nodded eagerly. ‘I was there when the report came in. Children out playing – God knows what they were doing out playing at that time, although I have my suspicions there – but anyway these children came across the body. Female, young, and…’ Ruge blushed again. ‘Well, naked.’

‘Naked? At minus 20 degrees. Is that what killed her?’

The policeman’s face got darker in colour still. ‘We don’t know yet,’ he mumbled.

A young woman, naked and dead – Stave had a creeping feeling he would be dealing with some dreadful crime. Since CID Chief Breuer put him in charge of a small investigation unit a few months back he’d had several murder cases. But this one seemed different from the usual stabbings amongst black marketeers or jealous scenes caused by soldiers returning from the war.

Ruge turned left into Landwehr Strasse, and eventually halted by the ruins of the train tracks running across the road. Stave got out and looked around. And shivered. ‘St Mary’s Hospital isn’t far,’ he said. ‘They must have a telephone. We can report in there. After you’ve taken me to the location of the body.’

Ruge clicked his heels. A young woman dragging a mangled tree stump in a cart behind her gave them a suspicious glance. Stave could see that her fingers were swollen with the cold. When she noticed him looking, she grabbed hold of the cart and hurried off.

Stave and Ruge clambered over the railway tracks, the stone ballast frozen together in lumps, tracks jutting up like bizarre sculptures. Beyond lay Baustrasse, only recognisable as a boundary line of the gutted, roofless tenement houses, their black walls stretching for hundreds of metres. Even now, so many months on, it still reeked with the bitter stench of burnt wood and fabric.

Two uniformed policemen, stamping their feet and clapping their hands in the cold, were standing in front of a crooked wall, three storeys high and looking like the slightest cough would bring it tumbling down to crush the policemen.

Stave didn’t call out to them, just lifted his hand in greeting, as he carefully made his way over the rubble. At least he didn’t have to make an effort to conceal his limp. There was nowhere here that anyone could walk straight.

One of the two uniforms raised his right hand in a salute, pointing to one side with his left. ‘The body is over there, next to the wall.’

Stave looked to where he was pointing. ‘Nasty business,’ he muttered.

A young woman. Stave put her at between 18 and 22 years of age, 1.60 metres, mid-blond, medium-length hair. Blue eyes staring into nothingness.

‘Pretty,’ murmured Ruge, who had come over to join him.

Stave stared at the policeman until he squirmed, then turned his gaze back to the corpse. No point in embarrassing his young colleague; the kid was only trying to hide his nerves.

‘Go down to the hospital and report in,’ he told him. Then Stave bent down beside the corpse, taking care not to touch it or the rubble on which she was lying, as if spread out on a bed.

It looks staged, Stave thought instinctively. And yet at the same time she’d been well hidden, behind the wall and a few higher piles of bricks. As far as he could tell, her body appeared to be unmarked, not even a scratch or a bruise, her hands spotless. She didn’t put up a fight, he thought to himself. And those aren’t worker’s hands; this is no rubble clearer, no housemaid, no factory worker.

His gaze slowly moved down her body. Flat stomach, a line down the right side: an old, well-healed appendectomy scar. Stave pulled out his notebook and wrote it down. The only thing he could see was a mark around her neck, a dark red line on her pale skin, barely three millimetres wide, all the way round her neck at the level of the larynx, more noticeable on the left than the right.

‘Looks like she’s been strangled. Perhaps with a narrow cord,’ Stave said to the two shivering uniforms, scribbling his observations down in his notebook. ‘Take a look and see if you can find any wire lying around. Or a cable of some sort.’

The pair rummaged around sullenly amidst the ruins. At least they were out of his way. He didn’t believe either of them would find anything. There were some dark lines in the hoar frost suggesting something might have been dragged along here, but unfortunately one of the slovenly uniforms had trodden all over them. The murderer probably killed his victim elsewhere and dragged her here.

‘Pretty corpse,’ somebody behind him said. The throaty voice of a chain smoker. Stave didn’t need to turn round to know who was standing behind him.

‘Good morning, Doctor Czrisini,’ he said, getting to his feet. ‘Good of you to come so quickly.’

Doctor Alfred Czrisini – small, bald, dark eyes large behind his round horn-rimmed spectacles – didn’t bother to take the glowing British Woodbine cigarette from between his blue lips as he spoke. ‘Looks like there wasn’t much need for me to hurry,’ he mumbled. ‘A naked body in this cold – I could have taken another couple of hours.’

‘Frozen stiff.’

‘Better preserved than in the mortuary. It’s not going to be easy to establish a time of death. Over the past six weeks the temperature has not risen above minus 10. She could have been lying here for days and still look as fresh as a daisy.’

‘Fresh as a daisy isn’t exactly how I’d describe her current condition,’ Stave grumbled. He looked around. Baustrasse had once been a working-class district with dozens of tenement buildings, reddish-brown, brick-built, five storeys, well looked after, trees along the street. Artisans, manual workers, tradespeople had lived here. All gone now. Stave could see little more than a landscape of fallen walls, stumps of burnt trees, heaps of rubble. Only one building still stood, on the right, at the end of the street: the yellow-plastered building of the St Matthew Foundation, an orphanage. Preserved from the rain of bombs as if by a miracle.

‘Two kids from the home found the body,’ one of the uniforms said, nodding towards building.

Stave nodded back. ‘Very well. I’ll talk to them shortly. And that, doctor, makes your task in determining time of death a little bit easier. If she’d been lying here for any length of time, the lads from the home would have found her ages ago.’

He liked the pathologist. The man’s name – pronounced ‘Chisini’ – had made him the brunt of jokes in the years after 1933, mostly threatening references to his Polish origins. Czrisini worked fast. He was a bachelor whose only two passions were corpses and cigarettes.

‘Are you thinking the same as I am?’ the doctor asked.

‘Rape?’

Czrisini nodded. ‘Young, pretty, naked and dead. It all fits.’

Stave shook his head from side to side. ‘At minus 20 degrees even the craziest rapist might get a bit worried about his favourite tool. On the other hand, he could have done the deed somewhere warmer.’ He nodded towards the drag marks. ‘She’s just been laid out here.’

‘We’ll only find out more when we’ve got her laid out on my dissection table,’ the pathologist replied cheerfully.

‘But not her name,’ Stave muttered to himself. What if the killer didn’t strip her out of murderous lust? But as a cold, calculated decision? A naked woman in the middle of ruins where nobody has lived for years: ‘It’s not going to be easy to identify her.’

Not long after, the crime-scene officer turned up. He was also the official police photographer; CID didn’t have enough trained specialists. Stave pointed out the drag marks. The photographer bent down over the body. As his flash went off, Stave suddenly saw in his mind’s eye anti-aircraft fire from the roads, the brightly lit, slowly falling parachute flares the first British aircraft used to mark targets for the bombers coming behind them. He forced his eyelids closed.

‘Don’t forget the drag marks,’ he told the man again. The photographer nodded, silently; Stave had sounded angrier than he had intended.

Finally he had the police bring over the two young lads who had found the body: barely ten years old, pale, blue lips, shivering, and not just from the cold. Orphans. Stave wondered for a moment whether he should play the stern policeman, and quickly decided against it. He leaned down towards them, asked them their names in a friendly voice and told them there was no need to be frightened for being out on the streets so early.

Five minutes later he knew all there was to know about the case. The pair had lit out before breakfast to look for machine gun or flak cartridges. Every day there were kids out there finding live munition amidst the rubble, but there was no point in warning the two off. Stave could remember his own childhood. He would have done exactly the same thing. And what good would it have done if some adult had told him not to? Instead he asked them if they often came out her looking for things. They both said nothing for a bit, then shook their heads hesitantly: no, this was the first time. None of the other children had ever done it either. The St Matthew Foundation had only just started taking in children again. Stave took the two kids’ names and then sent them back to the orphanage.

‘Damn shame they’ve just moved here,’ he said, looking at the pathologist who was watching two porters carry the body off on a stretcher.

‘You mean you have nobody to prove that the body was left here only last night. You have to depend on me,’ Dr Czrisini said matter-of-factly, though there was a note of self-satisfaction in his voice.

Stave shot a questioning look at the scene-of-crime man who was going over the ground in ever widening circles.

‘Nothing,’ he replied. ‘No bits of clothing, not even a cigarette butt, no footprints, no fingerprints, and certainly no lengths of wire. But we’ll go over the whole ruined block.’

At that moment Ruge came clambering over the rubble, a little out of breath. ‘Those goddamn doctors in the hospital…’ he began.

‘Spare me the details,’ Stave said, waving whatever the man had to say wearily away. ‘Did you get through or not?’

‘Yes, after some lengthy discussion,’ the young policeman said, suppressed anger in his voice.

‘And?’

The policeman looked at him for a moment as if he didn’t know what he meant, then suddenly got it: ‘We – you, I mean – have. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...