- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

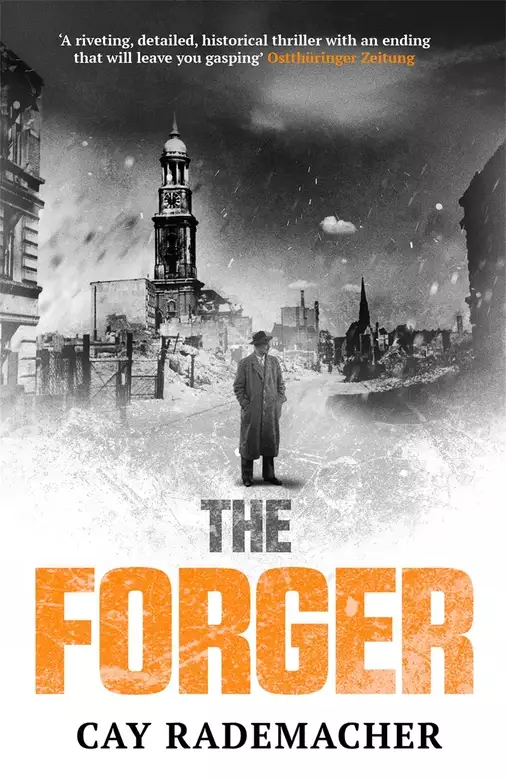

SHORTLISTED FOR THE CWA INTERNATIONAL DAGGER AWARD 2019 In a routine operation, Chief Inspector Frank Stave is shot down. He survives, but transfers from the murder commission to the office combatting the black market. There, Stave is confronted with an enigmatic case: Trummerfrau, women helping to clear rubble from Hamburg's bombed streets, discover works of art from the Weimar period - right next to a unidentified corpse. Shortly afterwards, mysterious banknotes whose existence disturbs the Allies' secret plans begin to pop up on the black market. The Supervisor soon discovers strange parallels between the two cases. With the introduction of a new currency, Stave thinks he is on the brink of a solution. But the truth is dangerous, and not just for him.

Release date: August 16, 2018

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 300

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Forger

Cay Rademacher

‘The novel provides a meticulously researched, oppressive and always instructive piece of German post-war history. Further sequels are absolutely welcome!’ KSTA

‘A captivating and authentic portrait of post-war Germany immediately before currency reform’ Oberhessic Press

‘A captivating, dazzling narrated crime novel that comes to the point without bloodthirsty gimmickry’ City Advice Westfalen

‘[The Murderer in Ruins] Undoubtedly the most powerful work of crime fiction I have read this year’ Independent

‘Vivid and harrowing’ Sunday Times

‘Once again, Rademacher combines an exciting crime story with a detailed description of Hamburg in the post-war period’ Aachener Nachrichten

‘Rademacher succeeds in describing history with tension’ Neue Presse

‘Rademacher understands how to draw a living picture of the postwar period. The Wolf Children allows its readers to embrace history without an instructive tone, wonderfully packaged in a thriller’ Hessische Allgemeine

‘With his follow-up to The Murderer in Ruins, Rademacher has once again captured an intriguing view into a not-so-distant world in which everyone is fighting for survival’ Brigitte

‘Impressively, Rademacher describes life in 1947 with all its hardships and hopes. A piece of history comes alive and is immensely touching’ Hamburger Morgenpost

‘The name Cay Rademacher stands for historical competence. [...] In addition to its thrilling crime plot, The Wolf Children also provides a lively presentation of the oppressive black market conditions in the post-war years’ Geislinger Zeitung/Südwest Presse

‘The book sheds a light on a world out of joint. [...] A crime thriller with level and depth. Highly recommended’ Buch-Magazin

‘This is not just a vivid historical lesson, The Wolf Children is a nerve-racking hunt for a murderer and a great crime novel’ NDR Hörfunk

‘Atmospheric, tight and gripping [...] A very successful mixture of crime and history’ Oberösterreichische Nachrichten

‘Exciting, authentic’ Gerald Schaumburg, Hessische Allgemeine

The wound

Wednesday, 31 March 1948

A bullet travels faster than sound. It hit Chief Inspector Frank Stave in the chest, before he even heard the noise of the gunshot. Struck him just below the heart, throwing him backwards into a pile of bricks from a collapsed wall. No pain, he thought to himself, I don’t feel any pain. That frightened him more than the blood streaming down his stomach from the wound, warm and sticky. Breathe slowly. The taste of iron in his mouth. A rushing in his ears. Stave pressed his right hand against the entry wound. He was lying on his back, staring upwards through the remnants of a roof into a low grey sky. Dust clouds danced in the air. There was a stench of mould and old mortar. He wished the pain would suddenly overwhelm him. But instead of pain it was darkness that overtook him, as his mind sank ever deeper into a sea of dark water. Please, pain, come. Now. If I don’t feel any pain, it means I’m going to die, thought Stave, before he stopped thinking altogether.

When he came to again, the pain was finally there: a fiery band of it burning through his chest, accompanied by a knife blade stabbing through his body with very breath. The chief inspector smiled with relief. White walls, blinding bright light eating its way into the back of his brain, the smell of disinfectant. A hospital. This time he didn’t fight back: he just let himself drift off. Sleep.

He was awakened by the sound of ragged breathing, as if someone buried up to the neck in fine sand was gasping for air. Stave opened his eyes. He listened to the gasping sound somewhere to his left. His breast was on fire. Carefully he touched the bandages, thick as blankets. He sat up. A thousand needles pierced his body. He felt faint and just managed to suppress a cry of pain; only a heavy sigh escaped his lips. The jagged breathing nearby stopped for a moment then started up again, still struggling. A ray of bright light to his right, coming through a half-open door. The hallway, Stave guessed. A hospital room. To his left he could make out the outline of a folding screen, obscuring from view his suffering neighbour.

Stave didn’t know which hospital he was in. He didn’t know how much time had passed since he had been shot. The Homicide Department had been looking for a man who had stabbed his wife to death outside their apartment in St Pauli. A ship's mate who had been on the warship Tirpitz, sunk in a Norwegian fjord in 1944. The junior officer had survived and had been captured in Scandinavia in 1945, but was soon released and came back to his family to one of the few houses in St Pauli that hadn’t been destroyed. All in all, someone who had come through the war relatively easily.

No obvious reason for the killing, though there were more than enough witnesses who had seen him attack his wife with the knife outside the door. He had fled and an arrest warrant had been issued. An evening call. Somebody had seen the suspect getting out of a tram on line 31 at the Baumwall stop, only a few hundred metres from the scene of the crime.

Stave had dashed there with all the uniformed police available. And indeed the former ship's mate had still been standing there at the tram stop, with no idea where he was going or what he was doing. He looked younger than the chief inspector had imagined. It was only when he spotted the patrol cars that he took off, eventually hiding in the bomb-blasted ruins of a chandler's shop. The chief inspector had some of the rubble moved to one side and crept carefully into the fire-blackened rooms. Not carefully enough. He had been expecting a killer armed with a knife, not a gun.

He wondered to himself if the murderer had shot more of his colleagues. If he had got away? Or if he had been overwhelmed and captured by the police? Maybe they had had to shoot him? He hoped they had managed to arrest him without further bloodshed — even if the result would be the same in the end: an English judge would send the killer to the gallows. It was even possible that it would be his friend, Public Prosecutor Ehrlich, who would make the speech calling for the death penalty. Stave would be called as a witness in court, his testimony the foundation stone on which the judge and the public prosecutor would build their case for the death penalty. He closed his eyes and hoped to fall asleep again.

But he was wide awake and there was nothing for him to do but lie there staring for hours into the darkness, occasionally touching his bandaged wound and listening to the hoarse breathing coming from behind the screen, breathing that seemed to get weaker as the night went on.

In the grey light of dawn the door opened. A young nurse came in, her pretty face narrow under her high starched hood. The Wehrmacht soldiers had called the nurses ‘Stukas’ because their hoods had bent wings like those of the dive bombers. Stave's son Karl had told him that. She wore a badge on her chest with her name: Franziska. He wished for a moment he could greet her with a joke, but nothing came to mind. ‘Where am I?’ he asked instead. He was horrified by how flat his voice sounded.

She gave him a brief smile. ‘Just a second, please,’ then she disappeared behind the screen. It was only then that it occurred to the chief inspector that it had been a long time since he had heard any breathing. The nurse hurried out of the room, then came back with another nurse; a doctor rushed past Stave's bed without even glancing at him. Whispered words behind the screen, surreal, like in one of those modern plays that were banned in the ‘brown’ days.

Eventually a bed was rolled out of the room. The CID man spared himself the pain of trying to sit up. Somebody folded up the screen, and all of a sudden his pillow was flooded with light from the high window. The space next to him was empty.

‘You’ve had a long leave of duty, Chief Inspector.’ It was an elderly doctor, with cropped steel-grey hair, a scar on his left cheek. A former army doctor, Stark reckoned.

‘Where am I?’

‘In Eppendorf University Hospital. Only the very best for servants of the state. You wouldn’t have survived your wound anywhere else. A bullet lodged in your lung. A few years ago there would have been nothing much we could have done. But we’ve had an enormous amount of experience with bullet wounds over recent years.’

‘I’m one of those who profited from the war.’

The medic laughed. ‘Aren’t we all?’

‘How long was I unconscious?’

‘You spent two weeks hovering between this world and the next. It was a close thing, but I’ve seen worse. In case you were hoping for early retirement I’m going to have to disappoint you. You’ll recover.’

‘Did they get the guy?’

The doctor shrugged his shoulders. ‘Not my department.’

‘Did he wound any of my colleagues, or even...’ Stave didn’t finish the sentence.

‘All I can say is that no other policeman was brought in here. Relax now. Sleep.’

‘I’ve been asleep for half a month.’

‘That's an order.’

Stave looked after the white coat as it waved its way towards the hallway. At first he thought the doctor's last sentence had been a joke, but then the chief inspector realised he had meant it seriously.

That afternoon they brought in a young man, little more than a child, barely conscious, his forehead covered by a thick bandage. As the nurses were pushing his bed in and setting up the screen, someone else came in: Stave's son. Very tall, very lean, his light blond hair a tad too long for Stave's liking, deep blue eyes. Damp patches on his faded coat and shoes that squelched on the linoleum floor.

‘Happy birthday,’ Stave mumbled. ‘I’m afraid I slept through it.’

Karl gave him a surprised look for a moment, then smiled briefly and was serious again. He had turned twenty on the second of April. ‘We can eat my birthday cake when you’re out again. If I’d known you were going to regain consciousness today I would have brought you flowers.’

‘From your allotment?’

‘Only tobacco growing there. I’d have taken some tulips from my neighbour's.’

‘Stolen goods? A fitting present for a copper.’

‘I’m glad to see you’re doing better.’

‘I’ll be back on duty tomorrow.’

‘Leave it until the day after.’

Silence. Stave looked at his son who was making awkward gestures to suggest he might help the nurses set up the screen, but he was actually getting in the way rather than helping them. What was Karl doing these days? As far as Stave knew, ever since his son had been released from a POW camp in Russia he’d been earning a living from the tobacco he grew on his allotment. I’ve only just come to, and already I’m worrying about him, he thought to himself. It’ll never end. He would have liked to go and see his son on the allotment more often, but somehow Karl had made him feel that he didn’t like having his father there.

He nodded towards Karl's coat. ‘Is it raining?’ The question was hardly necessary but he didn’t want to prolong the silence.

‘Nobody in Hamburg is in danger of dying of thirst at this time of year, that's for sure.’

‘Is that good or bad for tobacco-growing?’

The boy shrugged his shoulders indifferently. ‘Apropos tobacco,’ he whispered, leaning closer to his father. ‘I guess the Stukas would object if I lit up a cigarette?’

‘Sometimes it helps if you just stick a ciggy between your lips, but don’t light up. It calms the nerves. You shouldn’t smoke so much, it's not good for your lungs.’

Karl laughed so loud that Sister Franziska shot him a warning look over the top of the screen.

‘Your lung has more holes than mine,’ Karl said.

‘Do you know if they arrested the guy who did it?’

‘Yes, they got him. The shot got your colleagues’ adrenalin flowing. They overpowered him in among the ruins and...’ Karl hesitated briefly, ‘gave him a bit of a going-over.’

‘A going-over?’

‘The guy must have looked pretty bad by the time they finally had him behind bars. There was an article about it in Zeit. Just the one though, and it was short,’ he added quickly when he saw his father close his eyes.

That's something I’m going to have to explain to Cuddel Breuer, Stave thought. Maybe Prosecutor Ehrlich too. When something goes wrong, it goes really wrong. Even so, at least we got the killer.

They spent the next half hour in awkward chitchat. Stave had lots of things he would have liked to ask his son. When will you finally start doing something sensible? Have you made some new friends? Maybe a girlfriend? But Karl was always so evasive when things got personal. And the chief inspector didn’t have the energy to be persistent and perspicacious at the same time. The boy just made small talk, about the bad weather and an HSV football game. He flexed his hands and Stave noted the yellow nicotine stains on his fingers.

‘Go and have a smoke,’ he said. ‘I need a bit of a snooze.’

Karl nodded, obviously relieved. ‘I’ll come again in a day or two.’ He held up a hand, awkwardly, not quite a wave and something almost like a Heil Hitler gesture, then closed the door behind him.

The boy on the other side of the screen was humming a melody. Jazz, Stave thought to himself, as he closed his eyes in exhaustion.

But the pain, the pain he had longed so much to feel after being shot, now would not let him sleep. His thoughts wandered to Anna. How long had it been since he had last seen her? Six months? Was she even aware that he was in hospital? Don’t feel sorry for yourself, he cautioned.

His lover. Or rather his former lover. He remembered how last summer, at a jewellery pawnshop in the colonnades, Anna von Veckinhausen had exchanged a few thick bundles of Reichsmarks for a wedding ring. Had it been hers? He knew almost nothing about her life before she fled to Hamburg. Maybe there was somebody who knew more. The chief inspector recalled her irritated conversation with the public prosecutor in a café. The secret mission she was performing for Ehrlich: tracking down the pieces of his art collection that had been stolen by the Nazis. And the sad words she had spoken to him, Stave.

They had only been a couple for a few months, been to the theatre a few times, to restaurants, spent a few nights together, rare weekends of stolen togetherness. He had always had too much to do. And then Karl had come back from the war, and Stave hadn’t been able to deal with a son who had become a stranger and keep Anna at the same time. They had split up, without bitterness, more with resignation at having lost a battle.

He longed for Anna's smile, the scent of her hair, her skin. He thought of the meaningless chitchat with Karl. Of the days he had already frittered away in this hospital, and those he would still have to waste here until he had cobbled enough of himself back together again to leave. Of the ‘going-over’ his colleagues had given the shooter. Of CID Chief Cuddel Breuer, who was definitely going to want to know how this arrest had gone so terribly wrong.

Everything's gone wrong, the chief inspector said to himself, absolutely everything. In hospital with a perforated lung, and I have to lie here until I get the all-clear.

Stave counted every day he spent in that room. The grey light trickling through the window. The smell of disinfectant that permeated his pores. The tunes hummed from the other side of the screen. He didn’t exchange a single word with the boy, and the boy got no visitors, even though the hummed tunes, or so he imagined, got more light-hearted, louder. He even managed to force himself out of bed. What a triumph to be able to go to the toilet on his own, wobbling along the corridor, with his head spinning and his lung burning to be sure, but it was better than relieving himself on the shiny bedpan and then having to wait for the nurse to take it away.

Karl came by again four days later. They still didn’t have much to say to one another. On the fifth day Lieutenant MacDonald popped in.

‘I’m bringing you two medical items,’ the young British officer, with whom Stave had already solved two cases, told him, nodding at the brown paper bag in his hand. He dramatically pulled out a huge bar of chocolate. ‘Hershey's, genuine American calories. A comrade from the US Army gave it to me, but your ribs have more need of them than mine.’ Then he glanced at the screen, lowered his voice conspiratorially and pulled out of the bag a bottle full of amber liquid. ‘Whiskey, also from the American officer. “Old Tennessee”, lovingly nicknamed “Old Tennis Shoes” by its devotees. It's not exactly a Scottish single malt but it will get your pulse back up to speed.’

Stave gave a dry smile. ‘A couple of sips and on his next visit the doctor will have to revise his diagnosis.’

‘It's a miracle cure.’

‘How are Erna and the baby?’ Stave's former secretary and the young lieutenant had become involved in a relationship, with a few serious consequences: a chubby, healthy daughter called Iris, born the previous summer; a horrible divorce case in which she had lost custody of her eight-year-old son to her former husband, a bitter, crippled Wehrmacht veteran; her resignation from the CID ‘in best mutual interests’, because she could no longer take the looks her colleagues gave her; and her wedding, carried out by a British military chaplain, which had transformed her into ‘Mrs MacDonald’.

‘The little one's teething,’ the officer answered with a laugh. ‘I’m nostalgic for the war. The nights were quieter.’

‘Teeth won’t take as long to come through as peace did.’

‘Put a word in God's ear. That would be one thing less for Erna and me to worry about.’

Stave thought of Karl and the old saying that worries about children grow with them, but he didn’t mention it.

‘We need to get you out of here soon,’ MacDonald said, serious again. ‘We want to say goodbye properly.’

The chief inspector hoped his shock at the announcement didn’t show. ‘You’re being transferred?’

‘It looks as if I’ll be out of here this summer. Rumours going around the Officers’ Club suggest I can count on a posting within Europe.’

‘Will Erna and Iris go with you?’

‘Of course.’

‘And Erna's son.’

‘I hope it won’t break her heart to have to leave him here in Hamburg.’

‘Won’t you make another attempt to get custody?’

‘The judge was very clear on that. My superiors too. A good soldier knows when a battle is lost.’

Erna MacDonald, formerly Erna Berg, was paying a high price for her new life, Stave thought to himself. But then she wasn’t the only person in Hamburg who had paid a high price to be able to start over again after 1945.

Another day he had a more surprising visit: Police Corporal Heinrich Ruge, a young uniformed policeman who had accompanied him on several cases. Stave hardly recognised him because it was the first time he had seen his colleague in plain clothes — a dark suit with jacket sleeves far too short so that his skinny forearms stuck out like those of a wooden puppet.

‘I brought you something,’ he said, embarrassedly setting a thin wrapped-up parcel on the bedside table. Chocolate. A small fortune for a young uniformed policeman. I must really look emaciated, Stave thought, very touched. Ruge was the only one of his colleagues who had come to see him.

They chatted a bit. The longer the conversation went on, the more self-confident Ruge became. ‘It's a pity Frau Berg is no longer there.’

‘Mrs MacDonald now.’

Ruge blushed. ‘That takes a bit of getting used to. It sounds a bit different to “Müller” or “Schmidt”.’

‘You mean not “Germanic” enough?’ the chief inspector asked in the mildest of voices.

The policeman's face went even redder. ‘New times, new names. I don’t have a problem with that, quite the contrary. The lieutenant is...’ he searched for the right word, ‘so worldly wise. But some of our older colleagues have difficulties with the Veronikas.’

‘The Veronikas?’

‘That's what they call girls who go out with the Tommies.’

‘Is this just a CID thing? Or is it common all over Hamburg?’

‘All over. You know how it is, Chief Inspector. Suddenly a nickname like that pops up, from nobody knows where. But all of a sudden everybody's using it.’

‘I know how it is well enough. After 1933 overnight there were a few funny new names for certain people.’

‘Anyway, I want to join CID,’ Ruge suddenly let out. ‘I’ve already applied to do the entrance exam.’

The chief inspector looked at him long and hard. Should he encourage the kid? ‘Who was it gave the “going-over” to the Baumwall murderer after he was arrested?’ he asked eventually.

‘Chief Inspector Dönnecke.’

That old battleship. Cäsar Dönnecke, the man who’d been in CID since the days of the Kaiser. The man who, during the ‘brown years’, had carried out investigations with ‘colleagues’ from the Gestapo. And who had nonetheless somehow managed to get through the English ‘cleansing’ after the end of the war, even though the victors had fired men with less dirt on their hands than Dönnecke.

‘You can learn from people like him how not to behave.’

‘I’ll watch out for him. Maybe I might begin in your department.’ Ruge gave a shy laugh, then blushed again. ‘I mean, if I’m accepted, that is.’

And if I’m back in harness by then, Stave thought, but said nothing.

Later, after his visitor had left, the chief inspector stared up at the ceiling thinking to himself. About Erna Berg, Erna MacDonald. He wondered if she knew what her former colleagues were calling her? Of course she did. She knew everything that went on in CID; in fact she was usually the first to know. She probably knew before her pregnancy was that advanced that she wouldn’t be able to hold down the job. A ‘Veronika’. An Engländer flirt who abandoned the husband who’d lost a leg on the Eastern Front. Erna might not be so unhappy after all about her new husband's move.

Cäsar Dönnecke, Gestapo Dönnecke. The colleague who could give prisoners a ‘going-over’ without fearing the consequences.

‘I don’t belong there any more,’ Stave mumbled, half to himself. Suddenly the humming from the other side of the screen stopped. The chief inspector suppressed the curse that nearly escaped his lips. He had made a decision: I need to change departments, he told himself. Homicide is no longer for me.

Department S

Friday, 11 June 1948

Stave was standing next to the bronze elephant that the CID had nicknamed ‘Anton’. A work of art from the days when the CID headquarters had still been the head office of an insurance company, back in the long gone world of the twenties, before the war, when even the cold-blooded bean counters of a company could afford luxurious jokes such as a three-metre-high tonne-weight statue of an animal by their entrance. It was just 7 a.m. Even though it was one of the longest days of the year, the city was sunk in a grey light, fine veils of water hanging in the air, too heavy to be fog, too insubstantial to be rain; cold weather for an early summer day.

The chief inspector took off his thin, square-shouldered overcoat while he was still in the stairwell. He took his time. There was nobody to see him at such an early hour. He limped up the steps, with their crazily patterned tiles; his old ankle wound from the bombing nights was playing up. He felt his more recent wound too, although not so obviously: a scar across his chest, still rather red, longer than his index finger, but already well healed, the doctors had assured him. Every now and then there would be a pain, or rather a twinge when he moved too quickly. And the occasional difficulty breathing if he exerted himself. That would pass. In civilian clothes nobody noticed anything wrong with him, except that he was a bit more gaunt than he had been.

The corridor on the sixth floor was as abandoned as the Führerbunker had been in April 1945. The anteroom to his office had been the realm of Erna Berg. Erna MacDonald. He didn’t have a new secretary. Why would he? Initially, after the birth of Erna's daughter, there had been no qualified candidate. And then nobody had seen the point of installing someone as the secretary to a chief inspector lying in the University Hospital. The heavy black typewriter that had sat on her desk was gone. One or another of his colleagues had seen to that, Stave thought. Not that it mattered.

His office. A thin layer of dust on the desk, no new files, no new reports, no photos from the lab, no autopsy reports from Dr Czrisini. He pulled open the drawer of a metal filing cabinet with hanging folders containing the files of his solved cases. The unsolved ones must have been taken and. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...