- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

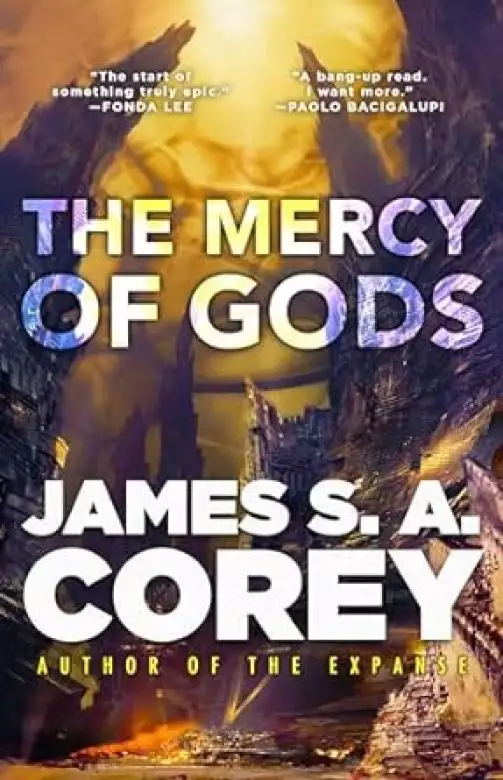

From the New York Times bestselling author of the Expanse comes a spectacular new space opera that sees humanity fighting for its survival in a war as old as the universe itself.

How humanity came to the planet called Anjiin is lost in the fog of history, but that history is about to end.The Carryx – part empire, part hive – have waged wars of conquest for centuries, destroying or enslaving species across the galaxy. Now, they are facing a great and deathless enemy. The key to their survival may rest with the humans of Anjiin.

Caught up in academic intrigue and affairs of the heart, Dafyd Alkhor is pleased just to be an assistant to a brilliant scientist and his celebrated research team. Then the Carryx ships descend, decimating the human population and taking the best and brightest of Anjiin society away to serve on the Carryx homeworld, and Dafyd is swept along with them.

They are dropped in the middle of a struggle they barely understand, set in a competition against the other captive species with extinction as the price of failure. Only Dafyd and a handful of his companions see past the Darwinian contest to the deeper game that they must play to survive: learning to understand – and manipulate – the Carryx themselves.

With a noble but suicidal human rebellion on one hand and strange and murderous enemies on the other, the team pays a terrible price to become the trusted servants of their new rulers.

Dafyd Alkhor is a simple man swept up in events that are beyond his control and more vast than his imagination. He will become the champion of humanity and its betrayer, the most hated man in history and the guardian of his people.

This is where his story begins.

Release date: August 6, 2024

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mercy of Gods

James S.A. Corey

You ask how many ages had the Carryx been fighting the long war? That is a meaningless question. The Carryx ruled the stars for epochs. We conquered the Ejia and Kurkst and outdreamt the Eyeless Ones. We burned the Logothetes until their worlds were windswept glass. You wish to know of our first encounter with the enemy, but it seems more likely to me that there were many first encounters spread across the face of distance and time in ways that simultaneity cannot map. The ending, though. I saw the beginning of that catastrophe. It was the abasement of an insignificant world that called itself Anjiin.

You can’t imagine how powerless and weak it seemed. We brought fire, death, and chains to Anjiin. We took from it what we deemed useful to us and culled those who resisted. And in that is our regret. If we had left it alone, nothing that came after would have been as it was. If we had burned it to ash and moved on as we had done to so many other worlds, I would not now be telling you the chronicle of our failure.

We did not see the adversary for what he was, and we brought him into our home.

—From the final statement of Ekur-Tkalal, keeper-librarian of the human moiety of the Carryx

Later, at the end of things, Dafyd would be amazed at how many of the critical choices in his life seemed small at the time. How many overwhelming problems had, with the distance of time, proved trivial. Even when he sensed the gravity of a situation, he often attributed it to the wrong things. He dreaded going to the end-of-year celebration at the Scholar’s Common that last time. But not, as it turned out, for any of the reasons that actually mattered.

“You biologists are always looking for the starting point, asking the origin question, sure. But if you want to see origins,” the tall, lanky man at Dafyd’s side said, pointing a skewer of grilled pork and apple at his chest. Then, for a moment, the man drunkenly lost his place. “If you want to see origins, you have to look away from your microscopes. You have to look up.”

“That’s true,” Dafyd agreed. He had no idea what the man was talking about, but it felt like he was being reprimanded.

“Deep sensor arrays. We can make a telescope with a lens as wide as the planet. Effectively as wide as the planet. Wider, even. Not that I do that anymore. Near-field. That’s where I work now.”

Dafyd made a polite sound. The tall man pulled a cube of pork off the skewer, and for a moment it looked like he’d drop it down into the courtyard. Dafyd imagined it landing in someone’s drink in the Common below.

After a moment, the tall man regained control of his food and popped it into his mouth. His voice box bobbed as he swallowed.

“I’m studying a fascinating anomalous zone just at the edge of the heliosphere that’s barely a light-second wide. Do you have any idea how small that is for conventional telescopy?”

“I don’t,” Dafyd said. “Isn’t a light-second actually kind of big?”

The tall man deflated. “Compared with the heliosphere, it’s really, really small.” He ate the rest of the food, chewing disconsolately, and put the skewer down on the handrail. He wiped his hand with a napkin before he extended it. “Llaren Morse. Near-field astronomic visualization at Dyan Academy. Good to meet you.”

Taking it meant clutching the man’s greasy fingers in his own. But more than that, it meant committing to the conversation. Pretending to see someone and making his excuses meant finding another way to pass his time. It seemed like a small choice. It seemed trivial.

“Dafyd,” he said, accepting the handshake. When Llaren Morse kept nodding, he added, “Dafyd Alkhor.”

Llaren Morse’s expression shifted. A small bunching between his eyebrows, his smile uncertain. “I feel like I should know that name. What projects have you run?”

“None. You’re probably thinking of my aunt. She’s in the funding colloquy.”

Llaren Morse’s expression went professional and formal so quickly, Dafyd almost heard the click. “Oh. Yes, that’s probably it.”

“We’re not actually involved in any of the same projects,” Dafyd said, half a beat too quickly. “I’m just putting in my time as a research assistant. Doing what I’m told. Keeping my head down.”

Llaren Morse nodded and made a soft, noncommittal grunt, then stood there, caught between wanting to get out of the conversation and also to keep whatever advantage the nephew of a woman who controlled the funding purse strings might give him. Dafyd hoped that the next question wouldn’t be which project he was working for.

“Where are you in from, then?” Llaren Morse asked.

“Right here. Irvian,” Dafyd said. “I actually walked from my apartments. I’m not really even here for the—” He gestured at the crowd below them and in the galleries and halls.

“No?”

“There’s a local girl I’m

hoping to run into.”

“And she’ll be here?”

“I’m hoping so,” Dafyd said. “Her boyfriend will.” He smiled like it was a joke. Llaren Morse froze and then laughed. It was a trick Dafyd had, disarming the truth by telling it slant. “What about you? You have someone back at home?”

“Fiancée,” the tall man said.

“Fiancée?” Dafyd echoed, keeping his voice playful and curious. They were almost past the part where Dafyd would need to say anything more about himself.

“Three years,” Llaren Morse said. “We’re looking to make it formal once I get a long-term placement.”

“Long-term?”

“The position at Dyan Academy is just a two-year placement. There’s no promise it’ll fund after that. I’m hoping for at least a five-year before we start putting real roots down.”

Dafyd sank his hands in his jacket pockets and leaned against the railing. “Sounds like stability’s really important for you.”

“Yeah, sure. I don’t want to throw myself into a placement and then have it assigned out to someone else, you know? We put a lot of effort into things, and then as soon as you start getting results, some bigger fish comes in and swallows you.”

And they were off. Dafyd spent the next half hour echoing back everything Llaren Morse said, either with exact words or near synonyms, or else pulling out what Dafyd thought the man meant and offering it back. The subject moved from the academic intrigue of Dyan Academy to Llaren Morse’s parents and how they’d encouraged him into research, to their divorce and how it had affected him and his sisters.

The other man never noticed that Dafyd wasn’t offering back any information about himself.

Dafyd listened because he was good at listening. He had a lot of practice. It kept the spotlight off him, people broadly seemed more hungry to be heard than they knew, and usually by the end of it, they found themselves liking him. Which was convenient, even on those occasions when he didn’t find himself liking them back.

As Morse finished telling him about how his elder sister had avoided romantic entanglements with partners she actually liked, there was a little commotion in the courtyard below. Applause and laughter, and then there, in the center of the disturbance, Tonner Freis.

A year ago, Tonner had been one of the more promising research leads. Young, brilliant, demanding, with a strong intuition for the patterns that living systems fell into and growing institutional support. When Dafyd’s aunt had casually nudged Dafyd toward Tonner Freis by mentioning that he had potential, she’d meant that ten years down the line when he’d paid his dues and worked his way to the top, Freis would be the kind of man who could help the junior researchers from his team start their careers. A person Dafyd could

attach himself to.

She hadn’t known that Tonner’s proteome reconciliation project would be the top of the medrey council report, or that it would be singled out by the research colloquy, high parliament review, and the Bastian Group. It was the first single-term project ever to top all three lists in the same year. Tonner Freis—with his tight smile and his prematurely gray hair that rose like smoke from an overheated brain—was, for the moment, the most celebrated mind in the world.

From where Dafyd stood, the distance and the angle made it impossible to see Tonner’s face clearly. Or the woman in the emerald-green dress at his side. Else Annalise Yannin, who had given up her own research team to join Tonner’s project. Who had one dimple in her left cheek when she smiled and two on her right. Who tapped out complex rhythms with her feet when she was thinking, like she occupied her body by dancing in place while her mind wandered.

Else Yannin, the research group’s second leader and acknowledged lover of Tonner Freis. Else, who Dafyd had come hoping to see even though he knew it was a mistake.

“Enjoy it now,” Llaren Morse said, staring down at Tonner and his applause. The small hairs at the back of Dafyd’s neck rose. Morse hadn’t meant that for him. The comment had been for Tonner, and there had been a sneer in it.

“Enjoy it now?” But he saw in the tall man’s expression that the trick wouldn’t work again. Llaren Morse’s eyes were guarded again, more than they had been when they’d started talking.

“I should let you go. I’ve kept you here all night,” the tall man said. “It was good meeting you, Alkhor.”

“Same,” Dafyd said, and watched him drift into the galleries and rooms. The abandoned skewer was still on the guardrail. The sky had darkened to starlight. A woman just slightly older than Dafyd ghosted past, cleaning the skewer away and disappearing into the crowd.

Dafyd tried to talk himself out of his little feeling of paranoia.

He was tired because it was the end of the year and everyone on the team had been working extra hours to finish the datasets. He was out of place at a gathering of intellectual grandees and political leaders. He was carrying the emotional weight of an inappropriate infatuation with an unavailable woman. He was embarrassed by the not-entirely-unfounded impression he’d given Llaren Morse that he was only there because someone in his family had influence over money.

Any one was a good argument for treating his emotions with a little skepticism tonight. Taken all together, they were a compelling case.

And on the other side of the balance, the shadow of contempt in Morse’s voice: Enjoy it now.

Dafyd muttered a little obscenity, scowled, and headed toward the ramp to the higher

levels and private salons of the Common where the administrators and politicians held court.

The Common was grown from forest coral and rose five levels above the open sward to the east and the plaza to the west. Curvilinear by nature, nothing in it was square. Subtle lines of support and tension—foundation into bracing into wall into window into finial—gave the whole building a sense of motion and life like some climbing and twisting fusion of ivy and bone.

The interior had sweeping corridors that channeled the breeze, courtyards that opened to the sky, private rooms that could be adapted for small meetings or living quarters, wide chambers used for presentations or dances or banquets. The air smelled of cedar and akkeh trees. Harp swallows nested in the highest reaches and chimed their songs at the people below.

For most of the year, the Common was a building of all uses for the Irvian Research Medrey, and it served all the branches of scholarship that the citywide institution embodied. Apart from one humiliating failure on an assessment in his first year, Dafyd had fond memories of the Common and the times he’d spent there. The end-of-year celebration was different. It was a nested series of lies. A minefield scattered with gold nuggets, opportunity and disaster invisibly mingled.

First, it was presented as a chance for the most exalted scholars and researchers of Anjiin’s great medrey and research conservatories to come together to socialize casually. In practice, “casual” included intricate and opaque rules of behavior and a rigidly enforced though ill-defined hierarchy of status. And one of many ironclad rules of etiquette was that people were to pretend there were no rules of etiquette. Who spoke to whom, who could make a joke and who was required to laugh, who could flirt and who must remain unreachably distant, all were unspoken and any mistake was noted by the community.

Second, it was a time to avoid politics and openly jockeying for the funding that came with the beginning of a new term. And so every conversation and comment was instead soaked in implication and nuance about which studies had ranked, which threads of the intellectual tapestry would be supported into the next year and which would be cut, who would lead the research teams and who would yoke their efforts to some more brilliant mind.

And finally, the celebration was open to the whole community. In theory, even the greenest scholar-prentice was welcome. In practice, Dafyd was not only one of the youngest people there, but also the only scholar-associate attending as a guest. The others of his rank on display that night were scraping up extra allowance by serving drinks and tapas to their betters.

Some people wore jackets with formal collars and vests in the colors of their home medrey and research conservatories. Others, the undyed summer linens that the newly appointed high magistrate had made fashionable. Dafyd was in his formal: a long charcoal jacket over an embroidered shirt and slim-fitting pants. A good outfit, but carefully

not too good.

Security personnel lurked in the higher-status areas, but Dafyd walked with the lazy confidence of someone accustomed to access and deference. It would have been trivial to query the local system for the location of Dorinda Alkhor, but his aunt might see the request and know he was looking for her. If she had warning… Well, better that she didn’t.

The crowd around him grew almost imperceptibly older as the mix of humanity shifted from scholar-researchers to scholar-coordinators, from support faculty to lead administrators, from recorders and popular writers to politicians and military liaisons. The formal jackets became just slightly better tailored, the embroidered shirts more brightly colored. All the plumage of status on display. He moved up the concentration of power like a microbe heading toward sugar, his hands in his pockets and his smile polite and blank. If he’d been nervous it would have shown, so he chose to be preoccupied instead. He went slowly, admiring art and icons in the swooping niches of forest coral, taking drinks from the servers and abandoning them to the servers that followed, being sure he knew what the next room was before he stepped into it.

His aunt was on a balcony that looked down over the plaza, and he saw her before she saw him. Her hair was down in a style that should have softened her face, but the severity of her mouth and jaw overpowered it. Dafyd didn’t recognize the man she was speaking with, but he was older, with a trim white beard. He was speaking quickly, making small, emphatic gestures, and she was listening to him intently.

Dafyd made a curve around, getting close to the archway that opened onto the balcony before changing his stride, moving more directly toward her. She glanced up, saw him. There was only a flicker of frown before she smiled and waved him over.

“Mur, this is my nephew Dafyd,” she said. “He’s working with Tonner Freis.”

“Young Freis!” Trim Beard said, shaking Dafyd’s hand. “That’s a good team to be with. First-rate work.”

“I’m mostly preparing samples and keeping the laboratory clean,” Dafyd said.

“Still. You’ll have it on your record. It’ll open doors later on. Count on that.”

“Mur is with the research colloquy,” his aunt said.

“Oh,” Dafyd said, and grinned. “Well, then I’m very pleased to meet you indeed. I came to meet with people who could help my prospects. Now that we’ve met, I can go home.”

His aunt hid a grimace, but Mur laughed and clapped Dafyd on the shoulder. “Dory here says kind things about you. You’ll be fine. But I should—” He gestured toward the back and nodded to his aunt knowingly. She nodded back, and the older man stepped away. Below them, the plaza was alive. Food carts and a band playing guitar music that gently reached up to where they were standing. Threads of melody

floating in the high, fragrant air. She put her arm in his.

“Dory?” Dafyd asked.

“I hate it when you’re self-effacing,” she said, ignoring his attempt at gentle mockery. Dafyd noted the tension in her neck and shoulder muscles. Everyone at the party wanted her time and access to the money she controlled. She’d probably been playing defense all night and it had stolen her patience. “It’s not as charming as you think.”

“I put people at ease,” Dafyd said.

“You’re at a point in your career that you should make people uneasy. You’re too fond of being underestimated. It’s a vice. You’re going to have to impress someone someday.”

“I just wanted to put in an appearance so you’d know I really came.”

“I’m glad you did,” and her smile forgave him a little.

“You taught me well.”

“I told my sister I would look out for you, and I swear on her dear departed soul I will turn you into something worthy of her,” his aunt said. Dafyd flinched at the mention of his mother, and his aunt softened a little. “She warned me that raising children would require patience. It’s why I never had any of my own.”

“I’ve never been the fastest learner, but that’s my burden. Your teaching was always good. I’m going to owe you a lot when it’s all said and done.”

“No.”

“Oh, I’m pretty sure I will.”

“I mean no, whatever you’re trying to soften out of me, don’t ask it. I’ve been watching you flatter and charm everyone all your life. I don’t think less of you for being manipulative. It’s a good skill. But I’m better at it than you, so whatever you’re about to try to dig out of me, no.”

“I met a man from Dyan Academy. I don’t think he likes Tonner.”

She looked at him, her eyes flat as a shark’s. Then, a moment later, the same tiny, mirthless smile she had when she lost a hand of cards.

“Don’t be smug. I really am glad you came,” she said, then squeezed his arm and let him go.

Dafyd retraced his steps, through the halls and down the wide ramps. His face shot an empty smile at those he passed, his mind elsewhere.

He found Tonner Freis and Else Yannin on the ground floor in a chamber wide enough to be a ballroom. Tonner had taken his jacket off, and he was leaning on a wide wooden table. Half a dozen scholars had formed a semicircle around him like a tiny theater with Tonner Freis as the only man on stage. The thing we’d been doing wrong was trying to build reconciliation strategies at the informational level instead of the product. DNA and ribosomes on one hand, lattice quasicrystals and QRP on the other. It’s like we were

trying to speak two different languages and force their grammars to mesh when all we really need are directions on how to build a chair. Stop trying to explain how and just start building the chair, and it’s much easier. His voice carried better than a singer’s. His audience chuckled.

Dafyd looked around, and she was easy to find. Else Yannin in her emerald-green dress was two tables over. Long, aquiline nose, wide mouth, and thin lips. She was watching her lover with an expression of amused indulgence. Only for a second, Dafyd hated Tonner Freis.

He didn’t need to do this. No one was asking him to. It would take no extra effort to turn to the right and amble out to the plaza. A plate of roasted corn and spiced beef, a glass of beer, and he could go back to his rooms and let the political intrigue play itself out without him. But Else tucked a lock of auburn hair back behind her ear, and he walked toward her table like he had business there.

Small moments, unnoticed at the time, change the fate of empires.

Her smile shifted when she saw him. Just as real, but meaning something different. Something more closed. “Dafyd? I didn’t expect to see you here.”

“My other plans fell through,” he said, reaching out to a servant passing by with what turned out to be mint iced tea. He’d been hoping for something more alcoholic. “I thought I’d see what the best minds of the planet looked like when they let their hair down.”

Else gestured to the crowd with her own glass. “This, on into the small hours of the morning.”

“No dancing?”

“Maybe when people have had a chance to get a little more drunk.” There were threads of premature white in her hair. Against the youth of her face, they made her seem ageless.

“Can I ask you a question?”

She settled into herself. “Of course.”

“Have you heard anything about another group taking over our research?”

She laughed once, loud enough that Tonner looked over and nodded to Dafyd before returning to his performance. “You don’t need to worry about that,” she said. “We’ve made so much progress and gotten so much acclaim in the last year, there’s no chance. Anyone who did would be setting themselves up as the disappointing second string. No one wants that.”

“All right,” Dafyd said, and took a drink of the tea he didn’t want. One member of Tonner’s little audience was saying something that made him scowl. Else shifted her weight. A single crease drew itself between her eyebrows.

“Just out of curiosity, what makes you ask?”

“It’s just that, one hundred percent certainty, no error bars? Someone’s making a play to take over the research.”

Else put down her drink and put her hand on his arm. The crease between her eyebrows deepened. “What have you heard?”

Dafyd let himself feel a little warmth at her attention, at the touch of her hand. It felt like an important moment, and it was. Later, when he stood in the eye of a storm that burned a thousand worlds, he’d remember how it all started with Else Yannin’s hand on his arm and his need to give her a reason to keep it there.

Humans, everyone knew, didn’t belong on Anjiin.

How they’d gotten to the planet, why they’d come there, all of that was lost in the fog of time and history. A sect of Gallatians claimed that they’d arrived on a massive ship like Pishtah’s fabled ark, but one that traveled between stars. Serintist theologians said that God had opened a rift that let the faithful escape the death of an older universe where some terrible sin—opinions varied on its exact nature—had convinced the Deity that genocide was the lesser evil. Or, if you were open to a little more poetry, a giant bird had carried them from Erribi—the planet next closest to the sun—which had possibly been their homeworld until the sun grew angry and turned their fields to wastelands and boiled away their skies.

But the sciences could tell a story too, even if humanity’s faulty memory had smeared the details.

Life on Anjiin had begun billions of years before with a system of aperiodic quasicrystals of silicon, carbon, and iodine. That life had used the quasicrystals to pass on instructions to the next generation, with occasional mutations that made some organisms do a little better. Over long eons, a complex ecosystem grew in the Anjiin oceans and across its four vast continents.

And then three and a half thousand years before, and apparently out of nowhere, humans showed up in the fossil record with incredibly dense helical coils of lightly associated bases strung like beads on a necklace of phosphate. And not just humans. Dogs and cows and lettuce and wildflowers and crickets and bees. Viruses. Mushrooms. Squirrels. Snails. A whole biome unprecedented in the genetic history of the planet popped into being on an island just east of the Gulf of Daish. Then barely a century after that first appearance, something, no one was sure what, had turned most of that island into glass and black rock. And while whatever records those original settlers may have brought with them disappeared at that point, a few remnants of this new biome survived at the island’s edges and on the nearby continental coastline, and it had spread over the world like a fire.

These two trees of life covering the world of Anjiin usually ignored each other, apart from competing for sunlight and some minerals. Occasionally something would evolve a way to parasitize creatures from the other biochemical tradition for a few complex proteins, water, and salt. But the common wisdom was that the two biomes couldn’t be reconciled in any meaningful way. On a microscopic level, the oaks and alders that were cousins of humanity were just too different from the native akkae and brulam, no matter how similar they might look from a distance. Even where evolution had guided the shapes and colors and forms into similar solutions, at a fundamental level, the different life-forms of Anjiin could never really nourish each other.

Until Tonner Freis had found a way to translate between them, and changed everything.

“I simultaneously want more beer and also a little less beer than I’ve already had,” Jessyn said.

Irinna, sitting next to her, grinned. The Scholar’s Common rose up above them at the edge of the plaza. The lights cast up the building’s side shifted and pulsed and made the forest coral seem like it was waving in some vast current. Beyond it, the darkness of the sky and the bright of the stars.

Tonner and Else were at the Common, being the face of the celebrated team. Campar, Dafyd, and Rickar were… somewhere. There were only four of them at their little table. A casual passerby could have mistaken them for a family. Nöl as the craggy-faced, long-suffering father, Synnia as his gray-haired wife, Jessyn as the older daughter, and Irinna as the younger. It wasn’t true at all, except in the ways that it was.

“You’ve probably had enough, hm?” Nöl said. “No call to overdo it?”

Irinna slapped the table. “All call to overdo it. If not now, when?”

Nöl looked pained and cleared his throat, and Synnia took his arm. “They’re young, love. They bounce back faster than we do.”

“Fair point, fair point,” the old scholar-associate said.

Jessyn still remembered the first time she’d met the team. Tonner Freis, of course, and Else Yannin, who had just abandoned her own project to join his. Nöl had seemed imposing back then, crag-faced and laconic and faintly disapproving. She had expected him and his partner, Synnia, to harbor resentments at being only scholar-associates at their age. Instead, she’d found a kind of profound contentment in them despite their status in the medrey. Some days it made her question her own ambition.

“I’m going back home for a week at the end of break,” Irinna said. “Until then, I have nothing.”

“Nothing?” Synnia asked, but with a twinkle in her eye.

“Nothing,” Irinna said. “Nothing and no one. I’m not courting. I’m not finishing an extra run of datasets. I am, for once in my life, relaxing and taking time to recuperate.”

Jessyn grinned. “You say it now. But you know what’ll happen. Tonner is going to have an idea, and when he asks someone to look into it, you’re going to show up.”

“You’ll be there too,” Irinna said.

“I won’t have made a proclamation about not working over break, though.”

Irinna waved the point away like she was shooing gnats. “I’m drunk. Hypocrisy is the natural companion of beer.”

“Is it?” Nöl said. “I didn’t know.”

Jessyn liked Irinna because the junior researcher reminded her not so much of herself at a younger age, but of who she wished she’d been: smart, pretty, with the first green shoots of self-confidence starting to break through the soil of her insecurities. Jessyn liked Dafyd, wherever he was tonight, for his quiet utility. And Campar for his humor, and Rickar for his casual sense of fashion and his cheerful cynicism. And tonight, she loved all of them because they had won.

For months, they had worked together in their labs, spent more time there than at their homes. There was a sense of family that grew with exposure, a familiarity that was deeper than just work colleagues. It was the rhythm of intimacy. Without anyone ever making a point of it, Jessyn had come to know them all. She could predict when Rickar would want to recheck a protein assay and when he’d be willing to let a questionable data point stand. Which days Irinna would spend quiet and focused, and which she’d be garrulous and distracting. She knew from the taste of the coffee when Dafyd had made it and when it was Synnia.

When she wanted to, she could still remember the quiet in the room when the first uptake results had come through. A radioactive marker in a membrane protein that the native Anjiin biosphere used had shown

up in a blade of grass. It was so small, it could have been invisible, and it was also the hinge on which the world swung.

Their strange, awkward, haphazard little group had translated one tree of life to the other. Two utterly incompatible methods of heritability had been coaxed into sitting beside one another, working together. That little blade of grass had been the product of a biochemical marriage thousands of years in the making. For an hour, maybe a little less, the nine of them had been the only people in the world who knew about it.

As much as their success promised, as many accolades as they’d won, part of Jessyn still treasured the magic of that hour. It was a small secret that they’d all shared. An experience they could only speak to each other about, because they were the only ones who really understood the combination of awe and satisfaction. Even when Jessyn told her brother about it—and she told him everything—he could only ever guess what she meant.

Across the little square, a band started playing. Two trumpets, weaving in and out of synchrony while a drummer did something that managed to be both propulsive and intricate. Irinna grabbed Jessyn’s hand, tugging her up. Despite her usual reticence, Jessyn let herself be pulled. They joined the dance. It was a simple one. They’d all learned the steps in childhood, so they could all recall them in drunken adulthood. Jessyn let the music and euphoria carry her. I am part of the most successful research team in the world. I am not too anxious to dance in public. My brain isn’t betraying me today. Today is good.

When the dance ended, Nöl and Synnia had already gone, heading back, Jessyn assumed, to the little house they shared on the edge of the medrey’s landhold. Irinna drank the last of her beer and made a face.

“Flat?” Jessyn asked.

“And warm. But still celebratory. Thank you, by the way.”

“Thank me?”

Irinna looked down at her feet, then up again. She was blushing a little. “You and the others were very kind letting me be part of this.”

“We really weren’t,” Jessyn said. “You carried your part of the project all the way through.”

“Still…” Irinna said, then darted forward to kiss Jessyn’s cheek. “Still thank you. This has been the best year I’ve ever had. I’m grateful.”

“I am too,” Jessyn said, and then, as if by mutual understanding, they parted ways. The end-of-year carnival played out in the streets and alleyways: music and laughter and the self-important, drunken debates of scholars eager to prove to each other that each of them was the cleverest person in the conversation. Jessyn walked

through the night with her hands in her pockets and a sense of calm.

For a moment, she was apart from the medrey, even as she moved within it. In a demimonde built on status and intellectual prowess, her team was the apex. It wouldn’t be forever, but tonight, she had won. Tonight, she was good enough, and even the dark things in the back of her mind couldn’t pull down her mood.

The quarters she and her brother shared were in one of the older buildings. Not grown coral, but built from glass and stone. She liked it because it was old-fashioned and quiet. Jellit liked it because it was close to his lab and the noodle shop he frequented. Jellit wasn’t there. His workgroup was having their own celebration, no doubt. He’d be back by morning or he’d send her a message to let her know he was falling in bed with someone and not to expect him. He wouldn’t just vanish and leave her to worry.

She sat at their table, deciding whether she wanted food before she went to bed or just a tall glass of water. She found herself grinning. It was so rare to feel satisfied. It was so odd to know for certain that she’d done well. Tonner Freis and Else Yannin, Rickar, Campar, Irinna, Nöl, Synnia, and even in his way Dafyd Alkhor. The team that had cracked open the possibility of a new, integrated biology. Generations from now, the textbooks would talk about them and what they’d done.

Her system alerted. A message waiting for her. She expected it would be Jellit, but the flag was from Tonner Freis.

When his face appeared on the screen, Jessyn sobered. She’d seen his moods before enough to recognize rage.

“Jessyn, I need you to come to an emergency meeting tomorrow at the lab. And don’t mention it to anyone.”

The medrey’s laboratories had an eerie emptiness. Dafyd walked through flowing hallways and galleries and meeting spaces that during the year were busy with scholars and artisan-fabricators and on-site representatives of the colloquies. They were almost abandoned now. A pair of men in hard, plasticized coveralls were repainting one of the walls. A harried man sped by on some past-due errand. A sparrow that had found its way inside fluttered down the empty air of the halls, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...