- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

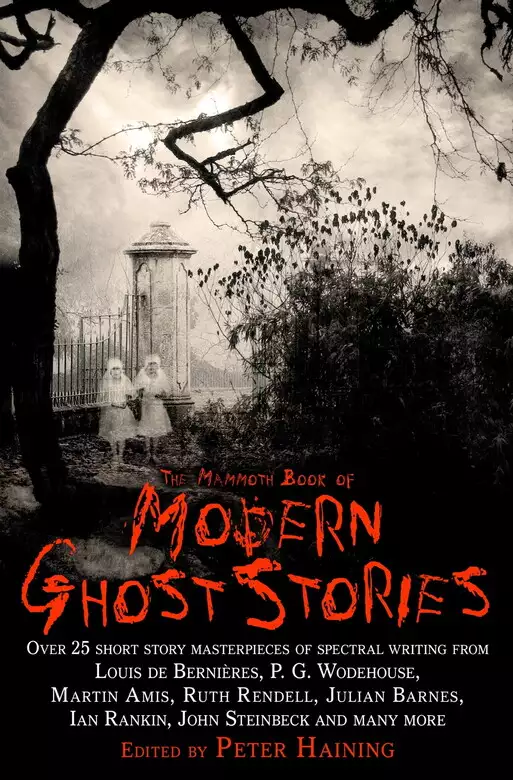

Over 25 short story masterpieces from writers such as Louis de Bernières and Ian Rankin - modern literary tales to chill the blood. This spine-chilling new anthology of 20th and 21st century tales by big name writers is in the best traditions of literary ghost stories. It is just a little over a hundred years ago that the most famous literary ghost story, The Turn of the Screw by Henry James, was published and in the intervening years a great many other distinguished writers have tried their hand at this popular genre - some basing their fictional tales on real supernatural experiences of their own.

Release date: March 23, 2010

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Modern Ghost Stories

Peter Haining

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica 5

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction 19

The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Dirty, Sick, X-Rated & Politically Incorrect Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Photography

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Famous Trials

The Mammoth Book of Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Great Detective Stories

The Mammoth Book of Great Inventions

The Mammoth Book of Hard Men

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Egypt

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Rome

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Battles

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: World War I

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: World War II

The Mammoth Book of Illustrated True Crime

The Mammoth Book of International Erotica

The Mammoth Book of IQ Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Kakuro, Worduko and Super Sudoku

The Mammoth Book of Killers at Large

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Erotica

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of On The Edge

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Perfect Crimes and Locked Room Mysteries

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Roman Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of SAS & Special Forces

The Mammoth Book of Secret Codes and Cryptograms

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock ’n’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Shipwrecks & Sea Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Short Erotic Novels

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Space Exploration and Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Special Ops

The Mammoth Book of Sudoku

The Mammoth Book of True Crime

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampires

The Mammoth Book of Vintage Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of War Comics

The Mammoth Book of Wild Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Women’s Fantasies

Acknowledgment is made to the following authors, agents and publishers for permission to reprint the stories in this collection.

“Ringing in the Good News” by Peter Ackroyd © 1985. Originally published in The Times, 24 December 1985. Reprinted by permission of Sheil Land

Associates Ltd.

“Who or What was It?” by Kingsley Amis © 1972. Originally published in Playboy magazine, November 1972. Reprinted by permission of PFD.

“A Gremlin in the Beer” by Derek Barnes © 1942. Originally published in The Spectator, June 1942 and reprinted by permission of the magazine.

“The Light in the Garden” by E. F. Benson © 1921. Originally published in Eve, December 1921. Reprinted by permission of the Executors of K. S. P.

MacDowall.

“Vengeance is Mine” by Algernon Blackwood © 1921. Originally published in Wolves of God, 1921. Reprinted by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd.

“Pink May” by Elizabeth Bowen © 1945. Originally published in The Demon Lover, 1945. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd.

“The Prescription” by Marjorie Bowen © 1928. Originally published in the London Magazine, December 1928. Reprinted by permission of the Penguin

Group.

“Another Fine Mess” by Ray Bradbury © 1995. Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1995. Reprinted by permission

of Abner Stein.

“My Beautiful House” by Louis de Bernières © 2004. Originally published in The Times, 18 December 2004. Reprinted by permission of Lavinia Trevor

Agency.

“The Pool” by Daphne du Maurier © 1959. Originally published in Breaking Point, 1959. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd.

“The Punishment” by Lord Dunsany © 1918. Originally published in Tales of War, 1918. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd.

“A Spot of Gothic” by Jane Gardam © 1980. Originally published in The Sidmouth Letters, 1980. Reprinted by permission of David Higham Associates.

“The Everlasting Club” by Arthur Gray © 1919. Originally published in Tedious Brief Tales of Granta and Gramarye, 1919. Reprinted by permission of W.

Heffer & Sons.

“Money for Jam” by Alec Guinness © 1945. Originally published in Penguin New Writing, 1945 and reprinted by permission of Christopher

Sinclair-Stevenson.

“South Sea Bubble” by Hammond Innes © 1973. Originally published in Punch magazine, December 1973. Reprinted by permission of the Estate of Ralph

Hammond Innes.

“Sir Tristram Goes West” by Eric Keown © 1935. Originally published in Punch magazine, May 1935. Reprinted by permission of the Estate of Eric

Keown.

“Smoke Ghost” by Fritz Leiber © 1941. Originally published in Unknown Worlds, October 1941. Reprinted by permission of Arkham House.

“The Duenna” by Marie Belloc Lowndes © 1926. Originally published in The Ghost Book, 1926. Reprinted by permission of the Executors of M. B.

Lowndes.

“The Bowmen” by Arthur Machen © 1914. Originally published in London Evening News, 29 September, 1914. Reprinted by permission of A. M. Heath Ltd.

“A Man From Glasgow” by Somerset Maugham © 1944. Originally published in Creatures of Circumstance, 1944. Reprinted by permission of William

Heinemann.

“The Ghost of U65” by George Minto © 1962. Originally published in Blackwood’s Magazine, July 1962. Reprinted by permission of William

Blackwood & Sons.

“Number Seventy-Nine” by A. N. L. Munby © 1949. Originally published in The Alabaster Hand, 1949. Reprinted by permission of the Estate of A. N. L.

Munby.

“A Visit to the Museum” by Vladimir Nabokov © 1963. Reprinted by permission of Esquire Publications Inc.

“The Party” by William F. Nolan © 1967. Originally published in Playboy, April 1967. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Haunted” by Joyce Carol Oates © 1987. Originally published in The Architecture of Fear, 1987. Reprinted by permission of Sara Menguc Literary

Agency.

“Underground” by J. B. Priestley © 1974. Originally published in Collected Stories of J. B. Priestley, 1974. Reprinted by permission of PFD.

“Video Nasty” by Philip Pullman © 1985. Originally published in Cold Feet, 1985. Reprinted by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd.

“Christmas Honeymoon” by Howard Spring © 1940. Originally published in the London Evening Standard, December 1940. Reprinted by permission of PFD.

“The Richpins” by E. G. Swain © 1912. Originally published in The Stoneground Ghost Tales, 1912. Reprinted by permission of W. Heffer & Sons.

“The Night the Ghost Got In” by James Thurber © 1933. Originally published in the New Yorker, September 1933. Reprinted by permission of the Estate of

James Thurber.

“The Inexperienced Ghost” by H. G. Wells © 1902. Originally published in the Strand magazine, March 1902. Reprinted by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd.

“The Ghost” by A. E. Van Vogt © 1942. Originally published in Unknown Worlds, October 1942. Reprinted by permission of Forrest J. Ackerman.

“Clytie” by Eudora Welty © 1941. Originally published in The Southern Review, Number 7, 1941. Reprinted by permission of the Penguin Group.

“The Haunted Chateau” by Dennis Wheatley © 1943. Originally published in Gunmen, Gallants and Ghosts, 1943. Reprinted by permission of Hutchinson

Publishers and the Estate of Dennis Wheatley.

“Full Fathom Five” by Alexander Woollcott © 1938. Originally published in the New Yorker, October 1938. Reprinted by permission of the New

Yorker.

Cambridge has the reputation of being a city of ghosts. With its centuries’ old colleges, streets of ancient buildings and a maze of small alleyways, the spirits of the

men and women who once lived and died in the area are almost tangible. Legends have long circulated about wandering spooks, numerous eyewitness reports exist in newspapers and books about restless

phantoms – the internet can also be employed to summon up details of several more – and a nocturnal “ghost tour” is a regular feature of the city’s tourist trail.

A story that is associated with one particular property, the Gibbs’ Building on The Backs, has intrigued me for years. The Gibbs is an imposing, three-story edifice, standing in the shadow

of King’s College Chapel: that wonderful example of Gothic architecture built in three stages over a period of 100 years. King’s itself was founded in 1441 by King Henry VI as an

ostentatious display of royal patronage and intended for boys from Eton College. It has, of course, boasted some distinguished if varied alumni over the years, including E. M. Forster, John

Bird and, most recently, Zadie Smith, when the college became one of the first to admit women.

Gibbs’ Building lies on the banks of the River Cam which, as its name suggests, gave the city its name. The area was first settled by the Romans at the southern edge of the Fens, a stretch

of countryside consisting mostly of marshes and swamps that were not properly drained until the 17th century. Cambridge evolved at the northernmost point, where the traveller was first confronted

by the ominous, dank Fens. Even then, stories were already swirling in from the darkness of strange figures and unearthly sounds that only the very brave – or foolish – would think of

investigating.

Today, of course, the whole countryside from Cambridge to the coast of East Anglia is very different. But a story persists in King’s College that a ghostly cry is still sometimes heard on

a staircase in Gibbs’ Building. The main authority for this is the ghost story writer, M. R. James, who came from Eton to Kings at the end of the 19th century and was allotted a room close to

the staircase. He never heard the cry, James explained in his autobiography, Eton and King’s (1926), but he knew of other academics who had. Out of a similar interest, I have

visited Cambridge on a number of occasions hoping to get to the bottom of the haunting. I had one fascinating discussion with a local author and paranormal investigator, T. C. Lethbridge, who

suggested a novel reason why the city had so many ghosts. It was due to being near the Fen marshes, he said. During his research, Lethbridge had discovered that ghosts were prevalent in damp areas

and came to the conclusion that they might be the result of supernatural “discharges” being conducted through water vapour. It was – and is – an intriguing concept.

But to return to the story of the Gibbs’ Building Ghost. Certainly there is some further evidence about it in the form of brief reports in the archives of the Society for Psychical

Research, which were given to the Cambridge University Library in 1991. However, though like M. R. James I have neither heard nor seen anything during my visits, there is a possible explanation as

to its cause of the phenomena.

It seems that a certain Mr Pote once occupied a set of ground floor rooms at the south end of Gibbs’ Building. He was, it appears, “a most virulent person”, compared by some

who crossed his path to Charles Dickens’ dreadful Mr Quilp. Ultimately, Pote was banned from the college for his outrageous behaviour and sending “a profane letter to the Dean”.

As he was being turned out of the university, Pote cursed the college “in language of ineffaceable memory”, according to M. R. James. Was it, then, his voice that has been

occasionally heard echoing around the passageways where he once walked? I like to think it might an explanation for a mystery that has puzzled me all these years – but as is the way of ghost

stories, I cannot be sure.

It comes as no great surprise to discover that M. R. James, who is now acknowledged to be the “Founding Father of the Modern Ghost Story”, should have garnered much

of his inspiration while he was resident in Cambridge. He was a Fellow at King’s and, as an antiquarian by instinct, could hardly fail to have been interested in the city’s enduring

tradition of the supernatural. Indeed, it seems that he was so intrigued by the accounts of ghosts that he discovered in old documents and papers – a number of them in the original Latin

– as well as the recollections of other academics, that he began to adapt them into stories to read to his friends. He chose the Christmas season as an appropriate time to tell these stories

and such was the reaction from his colleagues that the event became an annual gathering.

When James was later encouraged by his friends into publishing his first collection of these tales, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, in 1904, the public response was equally enthusiastic.

Within a few years the scholarly and retiring academic had effectively modernized the traditional tale of the supernatural into one of actuality, plausibility and malevolence well suited for 20th

century readers – banishing the old trappings of antique castles, terrified maidens, evil villains and clanking, comic spectres – and provided the inspiration for other writers who, in

the ensuing years, would develop the ghost story into the imaginative, varied and unsettling genre we know and enjoy today.

This book is intended to be a companion to my earlier anthology, Haunted House Stories (2005), as well as a celebration of the Modern Ghost Story ranging from the groundbreaking tales of

M. R. James to the dawn of the 21st century. A collection that demonstrates how and why the ghost has survived the march of progress that some critics once believed would confine it to the annals

of superstition. Defying, as it did so, the very elements that were expected to bring about its demise: the electric light, the telephone, cars, trains and aeroplanes, not forgetting modern

technology and psychology and, especially, the growth of human cynicism towards those things that we cannot explain by logic or reason.

I have deliberately divided the book into seven sections in order to try and show just how diversified it has become in the hands of some very accomplished and skilful writers, a considerable

number of them not specifically associated with the genre. After the landmark achievements of James and his circle, readers of supernatural fiction soon found the story-form attracting some of the

most popular writers of the first half of the 20th century – notably Conan Doyle, Kipling, Buchan, Somerset Maugham, D. H. Lawrence and Vladimir Nabokov – who created what amounted to a

“Golden Era” of ghost stories. However, the occurrence of two world wars in the first half of the century saw the emergence of a group of writers exploring the idea of life after death

as personified by ghosts, which offered an antidote to the appalling slaughter and suffering caused by the conflicts. Some of these stories were read as literally true by sections of the

population, obviously desperate for some form of comfort after the loss of dear ones. Among my contributors to this particular section you will find Arthur Machen with his famous story of

“The Bowmen”, Algernon Blackwood, Dennis Wheatley and Elizabeth Bowen. Plus one name I believe will be quite unexpected: that of Sir Alec Guinness, whose evocative ghost story at sea,

“Money For Jam”, I am delighted to be returning to print here for the first time since 1945!

The Gothic Story also returned revitalized to address new generations, thanks to the work of an excellent school of female writers, loosely categorized as “Ghost Feelers”. At the

forefront was the American Edith Wharton, who claimed it was a conscious act more than a belief to write about the supernatural. “I don’t believe in ghosts,” she said, “but

Em afraid of them.” Even with this reservation, Wharton and others went ahead to create the “new gothic” of claustrophobia, disintegration and terror of the soul, notably Marie

Belloc Lowndes, Eudora Welty, Daphne du Maurier and Jane Gardam. The humorous ghost story which Dickens had first interjected to entertain the readers of Pickwick Papers, the previous

century, got a life of its own thanks to a typically innovative story from H. G. Wells in 1902. His lead was followed by others of a similar sense of humour such as Alexander Woollcott, James

Thurber, Kingsley Amis and Ray Bradbury.

The book would, of course, be incomplete without a section devoted to the Christmas Ghost Story. Over the years, dozens of newspapers and magazines have echoed the words of the editor of

Eve magazine addressing his readers in 1921: “Ghosts prosper at Christmas time: they like the long evenings when the fire is low and the house hushed for the night. After you have sat

up late reading or talking about them they love to hear your heart beating and hammering as you steal upstairs to bed in the dark . . .” Here you will find Rider Haggard, Marjorie Bowen,

Hammond Innes, Peter Ackroyd and their seasonal compatriots vying to keep you firmly in your seat by the fireside.

The final selection sees the ghost story come of age as the 21st century dawns. It has now completed its evolution from the Medieval Tradition through the Gothic Drama and the Victorian Parlour

Tale. In a group of unique stories by Fritz Leiber, J. B. Priestley, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Pullman and Louis de Bernières you will encounter ghosts no longer confined in any way but

existing in the most everyday situations of modern living: inhabiting flats and houses, using the transport system, the phone, even the latest IT technology, for self-expression. You will find them

emancipated in a way no one could have imagined a century ago. As L. P. Hartley observed recently, “Ghosts have emancipated themselves from their disabilities, and besides being able to do a

great many things that human beings can’t do, they can now do a great many that human beings can do. Immaterial as they are or should be, they have been able to avail themselves of the

benefits of our materialistic civilisation.” A sobering thought, it seems to me, as technology presses ahead even faster and further in the 21st century.

I started my remarks with M. R. James and I will end with him, as he has been so influential on the ghost story genre. As he was dying, the great man was asked by another writer of supernatural

fiction, the Irishman Shane Leslie, to answer a question that had long been bothering him. Did James really believe in ghosts? The old man smiled slightly, lifted his white head and looked

his visitor straight in the eyes. “Depend upon it!” he said. “Some of these things are so, but we do not know the rules.” I suggest we may still be looking for those

rules at the end of the 21st century.

Peter Haining

June 2007

Location: Burnstow Beach, Suffolk.

Time: Spring, 1900.

Eyewitness Description: “It would stop, raise arms, bow itself toward the sand, then run stooping across the beach to the water-edge and back again; and

then, rising upright, once more continue its course forward at a speed that was startling and terrifying . . .”

Author: Montague Rhodes James (1862–1936) only wrote just over two dozen ghost short stories during the early years of the 20th century, but they have

continued to haunt each new generation of readers and inspire writers ever since. The son of a clergyman, he was raised in Suffolk, discovered traditional ghost tales while at his prep school, and

then decided to try his own interpretation of the genre when he became a Fellow of King’s College in 1887. By the dawn of the century, he was telling stories to friends at Christmas

gatherings in his room, jovially referred to as “meetings of the Chitchat Society” – though they were evidently anything but chatty in the shadowy, candle-lit gloom. All

James’ narratives bore out his conviction about ghosts: “I am prepared to consider evidence and accept it if it satisfies me.” The reader is invited to see whether he finds James

convincing in this opening story that is undoubtedly one of his most eerie and frightening.

“I suppose you will be getting away pretty soon, now Full term is over, Professor,” said a person not in the story to the Professor of

Ontography, soon after they had sat down next to each other at a feast in the hospitable hall of St James’s College.

The Professor was young, neat, and precise in speech.

“Yes,” he said; “my friends have been making me take up golf this term, and I mean to go to the East Coast – in point of fact to Burnstow – (I dare say you know it)

for a week or ten days, to improve my game. I hope to get off tomorrow.”

“Oh, Parkins,” said his neighbour on the other side, “if you are going to Burnstow, I wish you would look at the site of the Templars’ preceptory, and let me know if you

think it would be any good to have a dig there in the summer.”

It was, as you might suppose, a person of antiquarian pursuits who said this, but, since he merely appears in this prologue, there is no need to give his entitlements.

“Certainly,” said Parkins, the Professor: “if you will describe to me whereabouts the site is, I will do my best to give you an idea of the lie of the land when I get back; or

I could write to you about it, if you would tell me where you are likely to be.”

“Don’t trouble to do that, thanks. It’s only that I’m thinking of taking my family in that direction in the Long, and it occurred to me that, as very few of the English

preceptories have ever been properly planned, I might have an opportunity of doing something useful on off-days.”

The Professor rather sniffed at the idea that planning out a preceptory could be described as useful. His neighbour continued:

“The site – I doubt if there is anything showing above ground – must be down quite close to the beach now. The sea has encroached tremendously, as you know, all along that bit

of coast. I should think, from the map, that it must be about three-quarters of a mile from the Globe Inn, at the north end of the town. Where are you going to stay?”

“Well, at the Globe Inn, as a matter of fact,” said Parkins; “I have engaged a room there. I couldn’t get in anywhere else; most of the lodging-houses are shut up

in winter, it seems; and, as it is, they tell me that the only room of any size I can have is really a double-bedded one, and that they haven’t a corner in which to store the other bed, and

so on. But I must have a fairly large room, for I am taking some books down, and mean to do a bit of work; and though I don’t quite fancy having an empty bed – not to speak of two

– in what I may call for the time being my study, I suppose I can manage to rough it for the short time I shall be there.”

“Do you call having an extra bed in your room roughing it, Parkins?” said a bluff person opposite. “Look here, I shall come down and occupy it for a bit; it’ll be company

for you.”

The Professor quivered, but managed to laugh in a courteous manner.

“By all means, Rogers; there’s nothing I should like better. But I’m afraid you would find it rather dull; you don’t play golf, do you?”

“No, thank Heaven!” said rude Mr Rogers.

“Well, you see, when I’m not writing I shall most likely be out on the links, and that, as I say, would be rather dull for you, I’m afraid.”

“Oh, I don’t know! There’s certain to be somebody I know in the place; but, of course, if you don’t want me, speak the word, Parkins; I shan’t be offended. Truth,

as you always tell us, is never offensive.”

Parkins was, indeed, scrupulously polite and strictly truthful. It is to be feared that Mr Rogers sometimes practised upon his knowledge of these characteristics. In Parkins’s breast there

was a conflict now raging, which for a moment or two did not allow him to answer. That interval being over, he said:

“Well, if you want the exact truth, Rogers, I was considering whether the room I speak of would really be large enough to accommodate us both comfortably; and also whether (mind, I

shouldn’t have said this if you hadn’t pressed me) you would not constitute something in the nature of a hindrance to my work.”

Rogers laughed loudly.

“Well done, Parkins!” he said. “It’s all right. I promise not to interrupt your work; don’t you disturb yourself about that. No, I won’t come if you

don’t want me; but I thought I should do so nicely to keep the ghosts off.” Here he might have been seen to wink and to nudge his next neighbour. Parkins might also have been seen to

become pink. “I beg pardon, Parkins,” Rogers continued; “I oughtn’t to have said that. I forgot you didn’t like levity on these topics.”

“Well,” Parkins said, “as you have mentioned the matter, I freely own that I do not like careless talk about what you call ghosts. A man in my position,” he went

on, raising his voice a little, “cannot, I find, be too careful about appearing to sanction the current beliefs on such subjects. As you know, Rogers, or as you ought to know; for I think I

have never concealed my views—”

“No, you certainly have not, old man,” put in Rogers sotto voce.

“— I hold that any semblance, any appearance of concession to the view that such things might exist is to me a renunciation of all that I hold most sacred. But I’m afraid I

have not succeeded in securing your attention.”

“Your undivided attention, was what Dr Blimber actually said,”1 Rogers interrupted, with every appearance of an earnest desire

for accuracy. “But I beg your pardon, Parkins: I’m stopping you.”

“No, not at all,” said Parkins. “I don’t remember Blimber; perhaps he was before my time. But I needn’t go on. I’m sure you know what I mean.”

“Yes, yes,” said Rogers, rather hastily – “just so. We’ll go into it fully at Burnstow, or somewhere.”

In repeating the above dialogue I have tried to give the impression which it made on me, that Parkins was something of an old woman – rather henlike, perhaps, in his little ways; totally

destitute, alas! of the sense of humour, but at the same time dauntless and sincere in his convictions, and a man deserving of the greatest respect. Whether or not the reader has gathered so much,

that was the character which Parkins had.

On the following day Parkins did, as he had hoped, succeed in getting away from his college, and in arriving at Burnstow. He was made welcome at the Globe Inn, was safely

installed in the large double-bedded room of which we have heard, and was able before retiring to rest to arrange his materials for work in apple-pie order upon a commodious table which occupied

the outer end of the room, and was surrounded on three sides by windows looking out seaward; that is to say, the central window looked straight out to sea, and those on the left and right commanded

prospects along the shore to the north and south respectively. On the south you saw the village of Burnstow. On the north no houses were to be seen, but only the beach and the low cliff backing it.

Immediately in front was a strip – not considerable – of rough grass, dotted with old anchors, capstans, and so forth; then a broad path; then the beach. Whatever may have been the

original distance between the Globe Inn and the sea, not more than sixty yards now separated them.

The rest of the population of the inn was, of course, a golfing one, and included few elements that call for a special description. The most conspicuous figure was, perhaps, that of an ancien

militaire, secretary of a London club, and possessed of a voice of incredible strength, and of views of a pronouncedly Protestant type. These were apt to find utterance after his attendance

upon the ministrations of the Vicar, an estimable man with inclinations towards a picturesque ritual, which he gallantly kept down as far as he could out of deference to East Anglian tradition.

Professor Parkins, one of whose principal characteristics was pluck, spent the greater part of the day following his arrival at Burnstow in what he had called improving his game, in company with

this Colonel Wilson: and during the afternoon – whether the process of improvement were to blame or not, I am not sure – the Colonel’s demeanour assumed a colouring so lurid that

even Parkins jibbed at the thought of walking home with him from the links. He determined, after a short and furtive look at that bristling moustache and those incarnadined features, that it would

be wiser to allow the influences of tea and tobacco to do what they could with the Colonel before the dinner-hour should render a meeting inevitable.

“I might walk home to-night along the beach,” he reflected – “yes, and take a look – there will be light enough for that – at the ruins of which Disney was

talking. I don’t exactly know where they are, by the way; but I expect I can hardly help stumbling on them.”

This he accomplished, I may say, in the most literal sense, for in picking his way from the links to the shingle beach his foot caught, partly in a gorse-root and partly in a biggish stone, and

over he went. When he got up and surveyed his surroundings, he found himself in a patch of somewhat broken ground covered with small depressions and mounds. These latter, when he came to examine

them, pr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...