- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

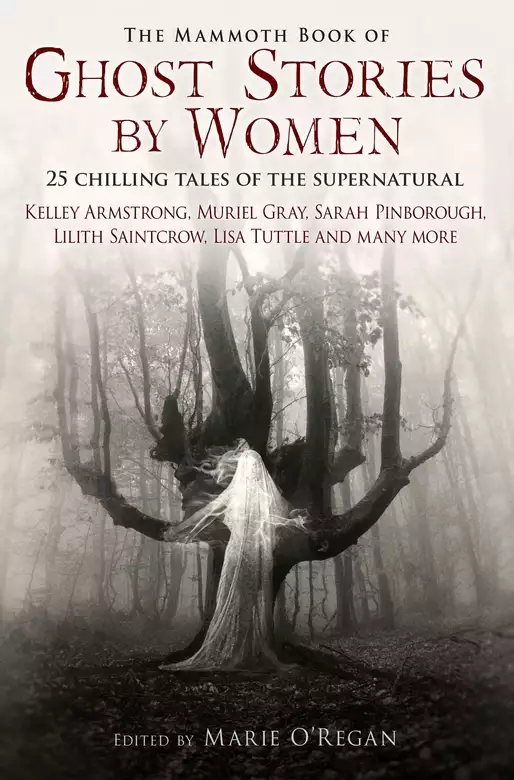

25 chilling short stories by outstanding female writers. Women have always written exceptional stories of horror and the supernatural. This anthology aims to showcase the very best of these, from Amelia B. Edwards's 'The Phantom Coach', published in 1864, through past luminaries such as Edith Wharton and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, to modern talents including Muriel Gray, Sarah Pinborough and Lilith Saintcrow. From tales of ghostly children to visitations by departed loved ones, and from heart-rending stories to the profoundly unsettling depiction of extreme malevolence, what each of these stories has in common is the effect of a slight chilling of the skin, a feeling of something not quite present, but nevertheless there. If anything, this showcase anthology proves that sometimes the female of the species can also be the most terrifying . . .

Release date: October 18, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Ghost Stories by Women

Marie O'Regan

Introduction copyright © Marie O’Regan 2012.

“Field Of The Dead” by Kim Lakin-Smith, copyright © 2012

“Collect Call” by Sarah Pinborough, copyright © 2012

“Dead Flowers by a Roadside” by Kelley Armstrong, copyright © 2012

“The Shadow in the Corner” by Mary Elizabeth Braddon, originally published in All the Year Round, 1879.

“The Madam of the Narrow Houses” by Caitlín R. Kiernan, originally published in The Ammonite Violin & Others (Subterranean Press, 2010). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Lost Ghost” by Mary E. Wilkins-Freeman, originally published in The Wind in the Rosebush and Other Stories of the Supernatural (Doubleday, 1903).

“The Ninth Witch” by Sarah Langan, copyright © 2012

“Sister, Shhh . . .” by Elizabeth Massie, copyright © 2012

“The Fifth Bedroom” by Alex Bell, copyright © 2012

“Scairt” by Alison Littlewood, originally published in Not One Of Us #43 (Not One of Us, 2010). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Seeing Nancy” by Nina Allan, copyright © 2012

“The Third Person” by Lisa Tuttle, copyright © 2012

“Freeze Out” by Nancy Holder, copyright © 2012

“Return” by Yvonne Navarro, copyright © 2012

“Let Loose” by Mary Cholmondeley, originally published in Moth and Rust (John Murray, 1902).

“Another One in from the Cold” by Marion Arnott, copyright © 2012

“My Moira” by Lilith Saintcrow, copyright © 2012

“Forget Us Not” by Nancy Kilpatrick, copyright © 2012

“Front Row Rider” by Muriel Gray, copyright © 2012

“God Grant That She Lye Still” by Cynthia Asquith. Originally published in When Churchyards Yawn (Hutchinson and Co., 1931). Reproduced by permission of Roland Asquith.

“The Phantom Coach” by Amelia B. Edwards, originally published in All the Year Round, 1864.

“The Old Nurse’s Story” by Elizabeth Gaskell, originally published in Famous Ghost Stories by English Authors, (Gowans & Gray, 1910)

“Among the Shoals Forever” by Gail Z. Martin, copyright © 2012

“Afterward” by Edith Wharton, originally published in The Century Magazine (The Century Co, 1910)

“A Silver Music” by Gaie Sebold, copyright © 2012

Ghost stories have always been my favourite kind of tale, especially in the short form. Recently I’ve read or re-read several pieces by women whose work I admire, both from the Victorian era and from today (Michelle Paver’s excellent novel Dark Matter and Susan Hill’s short novel The Small Hand spring to mind, as well as short stories such as Edith Wharton’s “Afterward”, to be found in this anthology) – while at the same time reading grumblings about the lack of “women in genre fiction”. The truth is that there isn’t really a lack, as such – women have always written in the horror and supernatural fields, and continue to do so. Proportionately, they form a smaller part of the genre as a whole. They are, however, a significant part, which leads me to this anthology.

I wanted to put together a collection of ghost stories – both old and new – that would showcase the talents of women in the genre, both past and present; and because there’s a wealth of talent out there, regardless of the writers’ gender.

These stories range from Amelia B. Edwards’s “The Phantom Coach”, which first saw print in 1864, through stories by such luminaries of the past as Edith Wharton, Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary E. Wilkins-Freeman, Mary Elizabeth Braddon and Mary Cholmondeley, right up to modern writers such as Lilith Saintcrow, Muriel Gray, Sarah Pinborough, Marion Arnott and Nina Allan. The subject matter covered is wide, from ghostly children to visitations by departed loved ones both human and animal, intended to warn, scare, or even comfort – Mary E. Wilkins-Freeman offers a genuinely heartrending spectral visitor in “The Lost Ghost”, while stories such as “The Fifth Bedroom” by Alex Bell (her first ghost story) show us a more malevolent creature by far.

Although the stories vary from tales of ghostly children to those of lost pets, from murder to accidental death, from rage to sorrow and back again, one thing is central to all: a slight chilling of the skin as you read. A feeling of something being not quite there but rather just behind you, ready to make itself known, and leaving you reluctant to turn out the light.

Enjoy the stories, and ladies – thank you for your help in bringing this anthology to print.

Marie O’ReganDerbyshire, England, November, 2011.

Dean Bartholomew Richards saw three figures at the periphery of his vision. Sunlight filtered through the stained glass and the Lady Chapel was transfigured. He tilted his chin to the blaze. Lichfield Cathedral was the Lord’s house, he told himself. It was not to be slighted by spirits.

A cold wind blew in from the direction of the altar. Dean Richards turned around slowly, the three figures shifting so that they continued to flicker at the corner of his eye. He walked past Saint Chad’s shrine and felt the temperature drop. Shadows lengthened. At his back, the sun went in.

Something wet touched the dean’s nose. He dabbed it with a sleeve. Staring up at the distant vaulting, he saw snow dusting down. He had heard about the phenomenon from the canons but hoped it was just the fantasies of young men left alone in a dark cathedral. But in his heart he could not deny the haunting had become more substantial. Sir Scott’s renovators were reporting screams like those of the damned, shadows writhing over walls, and spots of raging heat. Ice coated the Skidmore screen, a thousand tiny diamonds amongst the gilt. And then there were the children, their arrival always heralded by the inexplicable fall of snow.

Dean Richards rubbed the bulb of his nose. Faith must keep him stalwart.

“Come, children,” he whispered, fearing the words.

Snow dusted the flagstones. Silence packed in around him.

He spotted them at the foot of The Sleeping Children monument; two girls in white nightdresses – exact replicas of the dead sisters depicted in the marble monument. The elder child made the shape of a bird with interlaced fingers. The younger smiled. Snow settled on his shoulders, and he forced himself to advance to within several feet of the sisters. Kneeling on the cold flagstones, he clasped his hands.

“‘The Lord’s my shepherd, I’ll not want; he makes me down to lie’.” He heard the tremble in his voice but pressed on. The important thing was to focus on the appropriate passages. The Beatitudes for these pitiful, not-quite children? Or a parable to lead them to the light?

He fixed his gaze on his hands until curiosity got the better of him. Glancing up, he felt a jolt of fear. The girls had moved closer and now knelt side by side, their insubstantial hands joined in prayer. But the longer he stared at the ghosts, the more solid they became.

“‘In pastures green, he leadeth me—’”

The youngest girl’s lip curled back into a snarl.

“‘The quiet waters by—’”

The older sister flinched, a blur of movement.

To the dean’s horror, both underwent a metamorphosis. Eyes flickering shut, their skin turned silky white while their bodies stiffened and set.

The dean could not help himself. Forgetting the three spectres at the outer reaches of his vision, he stretched out a hand to comfort the poor dead children.

“Sleep now,” he whispered, hand hovering above the youngest’s exquisitely carved head. “In the arms of the Lord.” He lowered his hand to bless the girl.

The ghost girl’s eyes shot wide open, her sister’s too – stone angels brought to life. Their mouths strained and the screams of hundreds of men issued forth.

Dean Richards leaped back on to his feet. The noise was ear-splitting and unnatural. Flames burst from the flagstoned floor and licked the walls. Shadows writhed. The snow changed to falling ash.

“‘Our Father, which art in Heaven . . .’” The heat was terrible. “‘Hallowed be Thy name.’” Dean Richards felt searing pain and stared at his palms to see the flesh bubbling. Help me, my God, he cried inside, and aloud, “‘Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done!’”

He tried to run. The smell of burning bodies filled his nostrils and he tripped, his head pounding against the flagstones. His lips blistered around his prayer. The blackness set in.

Lichfield. City of philosophers. From the pig-in-a-poke cottages and elegant residences of Dam Street, to the shady sanctuary of Minster Pool, to the dung-and-fruit scented market place, Lichfield was glorious in its Middle Englishness.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in The Close. While the city walls and its south and west gates were long gone, the elite nature of the cathedral’s surrounding remained intact. Grand establishments housed the ecclesiastical and the educated in a square around the magnificent red-sandstone building.

The exception was the new breed of specialist who had taken up residence there. Stonemasons crawled about the western front of the cathedral like nibbling spiders. Hammers chinked. Chisels spilled red dust into the air.

On the afternoon of Monday, 22 October 1855, the strangest figures for miles around should have been the craftsmen at work on repairing the cathedral. But that changed the instant a troupe of five men came marching past the row of Tudor townhouses opposite the western front. Dressed in feathers and rags, they wore rings on their fingers and bells on their toes, and carried patchwork packs like colourful hunchbacks.

The stonemasons would later tell their families it was a change in the air which first alerted them to the mummers’ presence. Hanging off precipices many feet up, the men detected a country aroma. Their minds turned to hay ricks, windfalls, smoking jam kettles and bonfires. A few even smiled before they craned their necks to look down.

Sitting on the steps to one side of the courtyard, a set of plans across his knee, Canon Nicholas Russell detected the scent and was reminded of long summers spent at his grandmother’s cottage in Alrewas. But then he squinted over at the mummer troupe, with their multi-hued ragged tunics and sooty faces, and had visions of ungodly rituals enacted on chalk hills, of painted faces, and runes cast, and unfettered sensuality. Nicholas clutched the plans to his chest and got up.

The troupe arrived at the foot of the steps. Each man wore a variation of the rags. One had fantastically blue eyes and an embroidered red cross around his neck. Nicholas shuddered at the sight; it had a bloody and bandaged look. The next grinned like an imbecile, showing fat white teeth. This man wore a pair of stitched donkey’s ears on his head, and stood running what appeared to be a pin-on tail through his hands. A third man wore a tall black hat and was exceptionally thin. These three were peculiar in their own right, but it was the two figures to the fore of the group who disturbed Nicholas the most. One was a monster of a man with blackened eyes and green-painted skin to match his rags who wore a necklace of dead, dried things. The second was a boy of ten or so, wearing red horns and a doublet of scarlet rags.

“Good afternoon, gentlemen.” Nicholas hated the quiver in his voice.

The man in green nodded. “Isn’t it?” He inhaled deeply. “Lichfield in autumn. Reminds me of my childhood.”

“You’re a local man?” Nicholas eyed the weird fellow.

“Once upon a time. It probably takes a city as ghost-riddled as Lichfield to produce a man of my ilk.” He glanced back at his men and they shrugged agreement.

Ghost-riddled? Nicholas tensed. Had the stonemasons been gossiping? Certainly he and his fellow canons had done everything in their power to refute the rumours, but the apparitions would insist on appearing to clergy and laymen alike.

The leader of the troupe leaned in. That smell of mouldering fruit and damp straw . . . Nicholas almost choked against it.

“Word was put our way concerning Dean Richards’s recent incapacity.”

Nicholas tried to process the statement. The man’s flippancy grated. But before he could respond, the boy with the horns butted in.

“Want us to warm up them working folk, Mr Savage?” The boy produced a black velvet bag held by two sticks, almost identical to the collection purses used in the cathedral.

“Good idea, Thom. Go on now, fellas. Get us a crowd going.”

The devil boy and the other three climbed the stairs between Nicholas and the man in green. Leaving their organic perfume in the air, the four strode over to the scaffolded west front.

Mr Savage, as the devil boy had referred to him, called after them. “Ask after the best ale house. One with lodgings.” He arched a thick black eyebrow. “Some people need guidance. Without a strong hand, we’re as lost as lambs. And there are always wolves on the prowl, hey, minister?” The man’s shoulders shook in amusement. Tiny bells inside his clothing tinkled.

Nicholas folded the plans and slid them into a pocket of his cassock. “It is good to see a Lichfield son return to the fold. And now, if you will excuse me.” He glanced pointedly up at the late afternoon sky. “The weather sickens.”

He was about to hurry off when Mr Savage brought his huge green face closer. The man’s breath smelled of freshly dug soil. His eyes shone blue-white.

“Dean Richards sent word that he wishes to see me. Be a good fellow and lead the way.” His heavy brow bulged. “That’s a demand, Canon Nicholas.”

The Deanery was a red-brick Queen Anne mansion with tall chimneys and a central pediment. Ailen, the green man, imagined an interior dedicated to stoked fireplaces, plum pie and antique furnishings. Indeed, the house provided all of these things when a bustling housekeeper let them in – in spite of her clear alarm at Ailen’s costume. The comforts of the house did not extend to the dean’s bedroom, however. Following the faintly sanctimonious young canon across the threshold, Ailen was disappointed to find the room in semi-darkness and the air perfumed with lavender. Disappointed because he had hoped a strong-willed man like Dean Richards would not have taken ill after his fright.

“The Shakes,” Ailen muttered under his breath.

Canon Nicholas glanced back. “Excuse me?”

Ailen shook his head. “Nothing.”

A lamp burned low on the bedside cabinet. By its weak light, he saw eiderdowns piled high on a large bed, wall-mounted crucifixes, dried lavender arrangements – to soothe the nerves – and long tapestry curtains drawn tight to keep the cold out. Or something other.

Sound issued from beneath the eiderdowns. Muttered prayer – or, as Ailen understood it, just another form of incantation.

“Dean Richards?” said Nicholas.

The covers were thrown back. Dean Richards stared out, wild-eyed and with a halo of white hair about his head.

“Nicholas?” The Dean scrubbed his fists into his eyes. He blinked at Ailen, mole-like. “And you, friend? Are you phantom or mortal man?” A shiver visibly passed through the man and he hugged himself.

“Mortal, if in the guise of a handsome devil.” Ailen grinned – which prompted the dean to clutch the eiderdowns up to his chin.

“Forgive my crass humour, Dean Richards. It comes of a good many years spent on tour with a mummers’ troupe.”

“Mummers?” The dean chewed the word over. “The archbishop’s people mentioned a mummer. Pied Piper of the dead, they called him.”

“Aye. That’d be on account of this.” Reaching into his pack, Ailen pulled out a long metal pipe. Worked in silver and brass, the instrument appeared to be a cross between an oboe and a mechanical Chinese dragon. “I blow here.” Ailen pointed to the reed-tipped tail. “Notes are produced here.” He indicated a series of plated “gills” along the tail pipe. “I change pitch with these.” Two wing sections coruscated where the pipe fattened at the body section. “And here is the mouth.” He worked a series of nodules along the neck to exercise the metal jaw.

“So you are our Spirit Catcher?” Dean Richards relaxed his grip on the eiderdowns and sat up.

“What’s a Spirit Catcher?” The canon’s voice was laden with fear and judgement.

“The man who will cleanse our great cathedral of its unwelcome parishioners,” said the dean, rifling through the drawer of a bedside cabinet. “Ah.” He produced a purse and rested back against his pillows.

“Eight shillings and ninepence for the tall spirits. A crown apiece for the two girls.” He arched an eyebrow. “Half up front.” Loosening the string at the neck, he handed the purse to the canon. “Count it out please, Nicholas.”

The canon faltered. Ailen knew it pained the pious young man to play any part in the transaction. After all, such talk of ghosts bore more in common with the earth spirits entertained in pagan rites than with Christian doctrine. But Ailen could see many things others could not, including the canon’s desire to please his seniors and progress through the church hierarchy. He wasn’t surprised when Nicholas kept his concerns private and dug around inside the purse.

Dean Richards gestured to a chair off in the shadows. “Sit with me a while, Spirit Catcher. Let me tell you what I know.”

An hour later, the dean slipped back into his muttered prayer and strange hugging of the eiderdowns. Ailen stood up. Coins belonging to the church jangled in his pocket. He slid the dragon pipe back inside his pack and retrieved an envelope, which he presented to Nicholas.

“Arrowroot, garlic, lilac, mint, and mercury. Sprinkle the powder on the windowsills, the threshold and at the foot of the bed.”

Nicholas looked as if Ailen had handed him the severed hand of a baby.

“I want nothing to do with your witchcraft!”

“Then the Shakes will continue to pollute the dean. Leave him be or use this.” He held up the envelope pointedly then laid it down on top of the bedside cabinet. “Your choice.”

The King’s Head, Bird Street, reputedly opened its doors in 1495 and had since served as a coaching inn, birthed the Staffordshire regiment, and acquired its fair share of ghosts over the centuries.

Approaching the building, Ailen saw a silver-blue orb flicker at a window on the third floor. Voices came to him – men readying themselves for battle, their muskets and pikes knocking against armour as they moved. He was struck by a thick bitumen stench, felt the dry heat of flames. A woman screamed inside the public house. But the sound did not belong to the living. Instead, the scream looped back on itself and then faded.

Unlike the activities in the cathedral which the dean had described, these hauntings were moments in time caught in the King’s Head’s ancient footings. Even the screaming kitchen maid who had perished in a fire was just a shade. He saw her as he stepped into the bar. Most would experience her movement past them as a brief sensation of cold. Closing the door at his back, Ailen watched her sweep the floor, heedless of the patrons in her path.

He was brought back to the land of the living by a blackened face looming in.

“Cutting it close. But the crowd’s nice and eager. Here.” Willy Bones, part-time exorcist, full-time Fool, shoved a pint of ale into Ailen’s hand. “Quaff it quick. Our Saint’s about to announce us.”

Ailen sank a draught from the ale glass. The King’s Head had a generous quota of patrons, all gathered around the edges of the room to allow for a makeshift stage. Thom’s character, Little Devil, stood to the back alongside the anaemic Doctor, Naw Jones. Playing the part of Saint George, ex-clergyman Popule Brick faced the audience and bowed.

“Greeting, good patrons, and drunkards too, a merrysome Autumn eve to you.

“Our play today is fearsome bold, a tale of quandaries aeons old.

“I am Saint George—” A patriotic cry went up from the crowd. “I like to fight.”

Here Willy leaped in to deliver the rhyme. “He smites Man, wyrd worm and ass alike.”

Saint George crowed over the laughter and pointed at Willy.

“Lo, the Fool who pulls a tinkers cart, brays ‘eey-ore’, lifts his tail and f—”

Thom’s Little Devil danced in then.

“Far and wide doth search the godly saint, to fight the bad – or those that ain’t.

“But no good deed goes quite right, when the devil watches from the night.”

Thom withdrew. To the crowd’s delight, the Saint lunged at the Fool, wielding a squeezebox as a weapon. On the run, the Fool dashed over to Ailen, who offered up the mechanical dragon pipe. While the Saint played a jig on the squeezebox, the Fool brandished the dragon pipe. Steam belched from its jaws.

The audience “oohed” and “aahed” at the oddity. Willy the Fool made no attempt to play the pipe. Instead it was paraded as the worm mentioned in the verse – a puppet with gleaming scales and tick-tock inner workings.

Performing their ceremonial dance about the floor, the Saint succeeded in overpowering the dragon; Willy mimed the creature’s death throes then tossed it back to Ailen, who caught the pipe and tucked it back into his pack.

Running over to Popule, Willy announced, “Saint George has slain the worm fast and true, and now my sword will do for you.”

Willy stabbed the man in the belly with his finger. Popule howled and made a great show of staggering about the stage, to the general amusement of the spectators. At last, he collapsed and lay on his back.

Willy tugged on his donkey’s ears.

“Oh, Lord, he’s dead! Oh, me! Oh, my! Why’d that old windbag go and die?

“I’ll have to face the Queen’s cavaliers, and me not yet supped all my beers.”

Ailen strode out on to the stage. He stopped opposite Willy, the crowd clearly enthralled by his bulk and appearance.

“Behold! The woodland son, the Jack o’ the Green,” exclaimed Willy, sinking to one knee. He clasped his hands, imploring, “Oh, sacred son, do not judge me by this bloody scene. Indeed the knight deserved to die.” Willy pointed to his donkey’s ears. “He was a greater ass than I.”

Ailen held out his arms, the feathered sleeves of his tunic fanning out like wings.

“I cannot save this Christian son, who slayed my worm for sport and fun,

“But to save thee gross palaver, I’ll do away with the cadaver.

“In my wyld wood where fairies dwell, I’ll make his death a living hell!”

He swooped towards the onlookers, saw a flash of fear in their eyes accompanied by nervous smiles. At his back, Naw stepped forward, tall black hat exaggerating his height.

“At peace, Green Man, you know as I, all return to your wyld wood once they die.”

Naw switched his attention to Willy.

“Doctor Sham. I alchemize stone into gold, heal the sick and lame,

“Help spirits rest, clear unwelcome guests and raise the dead again.”

Willy the Fool butted in, “You raise the dead? Oh, say it’s so, and to the gallows I’ll not go.”

Naw kneeled down beside Popule, who rolled his eyes and stuck out his tongue. Holding out his arms in appeal to Willy, Naw spoke,

“This holy knight I can revive at your behest,

“For one-tenth your mortal soul – and the devil take the rest.”

Thom jigged from one foot to the other at the back of the stage. He hissed in a loud aside, “I’ve use for a foolish man, spread on toast like gooseberry jam.”

The Doctor waved his fingers over the prone Saint.

“Wake up, wake up, our noble son, there’s beer to sup now the play’s done.

“Arise, Saint George, with magic black, so this young fool escapes the rack.”

Popule staggered to his feet, reeling about the stage so that his audience leaned away, laughing and clutching their ale glasses tight. The Fool, the Doctor and the Saint joined hands and bowed as one. Thom began to circulate the pub, holding out his black velvet purse by its twin sticks and requesting mummers’ alms. Meanwhile, Ailen stepped forward and bowed. Sweeping out his feathered arms again, he delivered the final verse.

“It’s story’s end, night’s drawn in and we must bid farewell,

“To saints and fools and wyrd worms beneath our mummers’ spell.

“If we have cheered your autumn eve, please spare a coin or two; And so we take our final bows and bid goodnight to you.”

Ailen Savage knew it took a special breed of man to want to assist a Spirit Catcher. He had been born to it, his great-grandfather having originated the role. In the year 1754, as a young man fascinated by elemental folklore, Tam Savage had found a way to divine a restless spirit and capture it via a multi-metalled steam pipe. At a time when religion was in decline and science us providing the answer to many of life’s mysteries, Tam Savage had chosen to work alongside the local vicar as a Spirit Catcher. Perfecting his skills and instruments, he had passed the knowledge down to Ailen’s father, who in turn had passed it on to Ailen. Some argued it was a brutal business to hand on to a child. Ailen himself considered it no more dangerous than a life spent in Birmingham’s factories or down Leicestershire’s coal mines or taking a chisel to the worn-out heights of Lichfield’s cathedral.

Less obvious were the reasons why the others joined him.

“I can see the science in your method,” said the young canon, Nicholas. He hugged himself against the cool air, or the awesome sight of the cathedral veiled in early morning mist, Ailen wasn’t sure which. “That pipe contraption of yours . . . It has a heathen design but the science is no doubt godly.” Nicholas lowered his voice. “You are a man of breeding. Why take up with a mummers’ band?” He pointed ahead to the three men and the boy, dressed in costume and paint even at that hour.

“I’ll set you straight, Canon, because you aren’t a man to see past his own faith or social standing. Once, mind, and then no more will be said on it. Those men might be carved from God’s arse-end, but they are still of his flesh. There’s living and undead aplenty outside your great and glorious cathedral, and Willy, Thom, Naw and Pop have helped me separate the two more times than I care to remember. Take Willy there.” Ailen nodded at the man wearing the donkey’s ears. “He’s a product of Lancashire and Cajun blood. Look past the paint and you’ll see his features lean towards the exotic. Turns out Willy’s mother couldn’t take the Lancashire climate. Back home in her native Louisiana, she contracted typhoid fever – or became possessed, as Willy tells it. In the third week, she started to cut the flesh from her own bones. Willy lent himself out to every witch around – drawing water, mending what was broken, giving up food meant for his own mouth – all in a bid to learn the way to cast the demon out.”

Ailen’s eyes softened. “He didn’t learn enough in time to save her. After his mother’s death, Willy returned to Britain and put his skills as an exorcist to good use.” He placed a heavy hand on the canon’s shoulder. “The others have similar tales. We sniffed out the fear in each other – not fear of personal attack by the supernatural elements we encounter, but fear that we would not save others from those same dangers.”

Nicholas frowned. He took time over his words, as if adding to a stack of cards. “Please understand, Mr Savage. Dean Richards is in a vulnerable state and our cathedral . . . it houses some remarkable treasures.”

“And you think we may find those too great a temptation to pass over, being the lowly vagabonds that we are?”

“Not you, Mr Savage. You are an honest Lichfield son, no doubt. But the men you travel with are a coarser breed. By your own admission, one is part-negro—”

Ailen drew himself up. In that instant, he appeared less man than something gnarled and grown tall over hundreds of years. “Do not judge a man by his skin!” he thundered. The canon flinched as the mummer moved in close. “The very fact that spirits have survived beyond death and haunt your cathedral should be enough to illustrate our worth beyond the boundaries of flesh.”

A flicker of confusion crossed Nicholas’s face.

They were interrupted by Naw, materialized through the mist. He smiled, an expression that exaggerated his skeletal appearance.

“Mr Savage does love a good debate on subjects of a spiritual and religious nature. But he don’t always appreciate the force of his vigour.” Naw’s soft Welsh lilt instantly humanized him.

“Of course. It is good and right for a man to exercise his intellect. But my apologies, sir, we have not been introduced properly. I am Canon Nicholas Russell.”

Naw shook his hand. “Naw Jones of Cardiff. Mummer, spiritualist, historian.” He laughed kindly. “Please do not hold the latter against me.”

Nicholas looked newly floored by Naw’s generous spirit and evident education. Ailen almost felt sorry for the clergyman. He consulted a small brass pocket watch hidden amongst his tunic rags. “What time do the stonemasons start work?”

“At eight,” replied Nicholas.

“We have an hour.” Ailen pointed at the bunch of keys the canon carried. “Please accompany us inside. I will need to hear all the details you can offer on what has occurred within.” He slapped Naw on the back. “And, hopefully, our historian here can go some way to explaining why.”

“... very little in the way of restoration until the architect James Wyatt undertook repairs late last century. Wyatt’s idea was to c

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...