- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

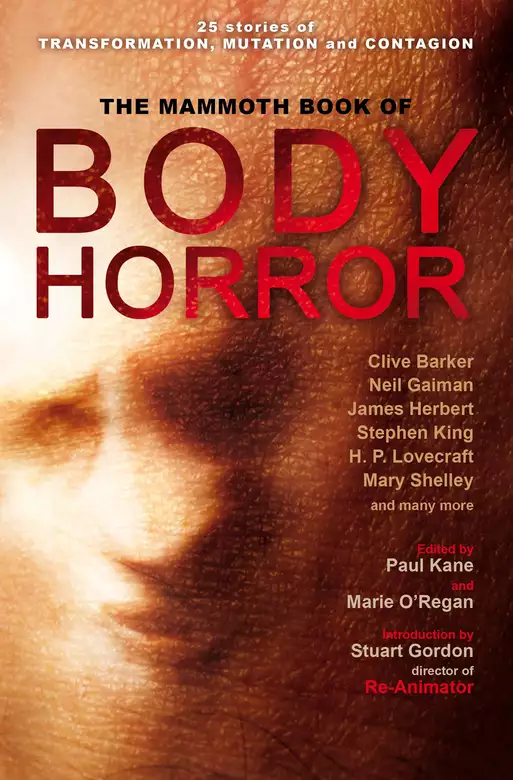

A gripping collection which offers for the first time a chronological overview of the popular contemporary sub-genre of body horror, from Edgar Allan Poe to Christopher Fowler, with contributions from leading horror writers, including Stephen King, George Langelaan and Neil Gaiman. The collection includes the stories behind seminal body horror movies, John Carpenter's The Thing, David Cronenberg's The Fly and Stuart Gordon's Re-Animator.

Release date: March 1, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Body Horror

Marie O'Regan

INTRODUCTION copyright © Stuart Gordon 2011.

TRANSFORMATION by Mary Shelley – Originally published in The Keepsake for MDCCCXXXI, 1831.

THE TELL-TALE HEART by Edgar Allan Poe 1843 – Originally published in The Pioneer, January 1843.

HERBERT WEST: RE-ANIMATOR by H.P. Lovecraft – Originally serialized in Home Brew, 1-6, February-July 1922.

WHO GOES THERE? copyright © 1938 – Originally published in Astounding, August 1938. Reprinted by permission of Barry N. Malzberg.

THE FLY copyright © 1957 – Originally published in Playboy, June, 1957. Reprinted by permission of William Langelaan.

TIS THE SEASON TO BE JELLY copyright © Richard Matheson 1963 – Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June 1963. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agent.

SURVIVOR TYPE copyright © Stephen King 1982 – Originally published in Terrors, 1982. Reprinted by permission of the author, his agent and Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.

THE BODY POLITIC copyright © Clive Barker 1985 – Originally published in Clive Barker’s Books of Blood Vol. 4, 1985. Reprinted by permission of the author.

THE CHANEY LEGACY copyright © Robert Bloch 1986 – Originally published in Night Cry, 1986. Reprinted by permission of the Estate of Robert Bloch.

THE OTHER SIDE copyright © Ramsey Campbell 1986 – Originally published in the 1986 World Fantasy Convention (Programme Book). Reprinted by permission of the author.

FRUITING BODIES copyright © Brian Lumley 1988 – Originally published in Weird Tales No. 291, Summer 1988. Reprinted with permission of the author and his agent, Barbara Lumley.

FREAKTENT copyright © Nancy A. Collins 1990 – Originally published in Splatterpunks: Extreme Horror, December 1990. Reprinted by permission of the author.

REGION OF THE FLESH copyright © Richard Christian Matheson 1991 – Originally published in Obsessions, 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author.

WALKING WOUNDED copyright © Michael Marshall Smith 1997 – Originally published in Dark Terrors 3: The Gollancz Book of Horror, 1997. Reprinted by permission of the author.

CHANGES copyright © Neil Gaiman 1998 – Originally published in Smoke and Mirrors: Short Fictions and Illusions, November 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

OTHERS copyright © James Herbert 1999 – Originally published in Others, 1999. Reprinted by permission of the author.

THE LOOK copyright © Christopher Fowler 2001 – Originally published in Urban Gothic: Lacuna and Other Trips, 2001. Reprinted by permission of the author.

RESIDUE copyright © Alice Henderson 2011

DOG DAYS copyright © Graham Masterton 2011

BLACK BOX copyright © Gemma Files 2011

THE SOARING DEAD copyright © Simon Clark 2011

POLYP copyright © Barbie Wilde 2011

ALMOST FOREVER copyright © David Moody 2011

BUTTERFLY copyright © Axelle Carolyn 2011

STICKY EYE copyright © Conrad Williams 2011

Body Horror. Not dead bodies. Your own body. And something is going very wrong. Inside. Your body is betraying you, and since it’s your own body, you can’t even run away.

Many people believe that Body Horror began in film. The first one I remember was David Cronenberg’s Shivers (or They Came From Within as it was called in its US release). It was 1975 and my wife Carolyn and I were watching it as part of a double bill at a drive-in. I can’t remember what the second film was; I didn’t make it that far. What I do remember was the sight of fist-sized parasites moving under people’s skins and shooting out their mouths into the next victim. Yuck! I started getting woozy. The best Body Horror makes your own body turn against you. Without thinking, I hit the accelerator of our car and tore the drive-in’s speaker right out of our side window as we careened crazily up and down the rows to make our escape.

David Cronenberg has made a career out of Body Horror: Rabid, Scanners and his masterpiece Dead Ringers about deranged twin gynaecologists. He is always inventing new organs, and in his remake of The Fly he built on his idea of “The New Flesh” from Videodrome. Speaking of The Fly, it’s very fitting that George Langelaan’s original story, the one that started it all, is presented in this stomach-churning collection. “Help me! Help me!”

But as Paul Kane and Marie O’Regan, the diabolical masterminds who assembled this truly disturbing book show us, Body Horror has been with us since long before there were movies. The grandad (or grandmum) here is Mary Shelley’s story “Transformation”. Everyone knows that Mary gave birth to Frankenstein when she was just a girl of eighteen. But “Transformation” was a revelation to me, and to anyone who may still think that her famous husband Percy Bysshe Shelley really did her ghost-writing. They’ll have to believe he did it from beyond the grave, as this story, with its shape-shifting dwarf, was written in 1831, nine years after his death. (A grim Body Horror footnote is that when Mary cremated Percy’s body, her friend pulled Shelley’s calcified heart from the flames. Mary carried it with her in a little velvet bag until she died aged fifty-four in 1851.)

It’s clear that if Mary Shelley hadn’t created Frankenstein, there would certainly be no “Herbert West – Reanimator” by H. P. Lovecraft. Her classic story was surely in his twisted mind when he penned the six-part serial for Home Brew Magazine in 1922. But Lovecraft always hated those stories. Why? Because he had been paid in advance to write them. He felt that the stories he created for himself, untainted by filthy lucre, were the true expressions of his tormented soul.

In fact, Lovecraft hated the Re-Animator stories so much that August Derleth, the man who saved his mentor from obscurity by republishing his stories after his death, failed to include these lurid tales of Herbert West and his ghastly experiments in his subsequent Arkham House editions. It wasn’t until 1983, when a young theatre director in Chicago went looking for them, that these tales again saw the light of day. How do I know this? Because I was that director.

I was bemoaning the fact that back then (like today) all Hollywood was producing were vampire stories. “Why doesn’t someone make a Frankenstein movie?” I complained to a friend. She asked me if I had ever heard of Herbert West. I’d thought I knew Lovecraft pretty well, but didn’t know what she was talking about. My curiosity was aroused and I began scouring old bookstores looking for the story. Finally, in desperation, I checked the card catalogue of the Special Collections at the Chicago Public Library. Amazingly there it was. I was told to fill out a postcard requesting the book, and several months later I received a notice to come to the huge downtown library.

When I got there it was like the scene in Citizen Kane. I was led to a large table and a book was removed from a metal box and placed in front of me. The librarian informed me that I could not take the book out of the building but would have to read it there, and when I was done return it to the metal box. As I began to turn the pages, the yellowed pulpy paper began to literally crumble in my hands. “Could I Xerox it?” I pleaded. The librarian thought about it for what seemed like an eternity and then nodded.

Reading the stories that night, I realized I had hit pay dirt. Unlike much of Lovecraft, which can be vague, internalized, arcane or just “too horrible to describe”, these stories were packed with action and bloody shocks. They rocketed along, getting more and more outlandish and horrific by the page. And they were funny. West’s recurring line, “It wasn’t quite fresh enough!” became a running joke, punctuating each disastrous failed experiment. It was love at first sight.

I’m thrilled that the stories have been republished due to the success of the film. I started reading Poe because of Roger Corman’s films and now I was returning the favour for Mr Lovecraft. Old H. P. has never been more popular. His books have moved from the Horror/Sci-fi shelves to Literature, and there are games, comic books and T-shirts galore. Merchandising! Too bad he didn’t live long enough to collect the residuals. And there has even been talk of a big-budget film adaptation of his masterwork At the Mountains of Madness. Unfortunately this project has yet to be greenlit; partly, I believe, because the story of a doomed expedition to Antarctica that discovers frozen alien corpses and makes the mistake of thawing them out has already been made . . . twice.

No, not the Lovecraft story, but a tale that borrowed many of the same elements. Instead of a vast, ancient alien-built city, here it’s a flying saucer under the ice. And, like Lovecraft’s shape-shifting Shogoths, we have The Thing, a creature that can become anyone or anything. Filmed three times, once in 1951 by Christian Nyby (with help from his mentor Howard Hawks) and again by John Carpenter in 1982, with a second remake due soon, this very popular story by John W. Campbell can be read in this collection under its original title, “Who Goes There?”. How did Campbell know about Lovecraft’s Mountains? It might have something to do with the fact that from 1937 to his death in 1971 he was the editor of Astounding Science Fiction (later Analog).

Lovecraft’s tentacles intertwine with several other stories in this volume. Robert Bloch, best known as the author of Psycho, and an actual disciple of Lovecraft, is represented here with “The Chaney Legacy”, which explores a very different type of shape-shifting. And Brian Lumley and Ramsey Campbell, who both continue to contribute to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, have a pair of stories you won’t be able to shake out of your mind: Lumley’s atmospheric (and elegantly disgusting) “Fruiting Bodies”, and Campbell’s hallucinogenic bad trip, “The Other Side”.

Let’s not forget Stephen King, who called Lovecraft “the twentieth century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale”. His story, “Survivor Type”, follows his own three rules of disturbing: try for Dread, if not dread, then Shock and if all else fails – go for Gross-out. (Don’t read this one on an empty stomach.)

Clive Barker borrows a few pages from W. F. Harvey’s “The Beast with Five Fingers” in a story that may tickle you in all the wrong places. And speaking of body image, you’ll never look at the fashion world in the same way again after “The Look” by Christopher Fowler.

But do yourself a favour and save Nancy A. Collins’s “Freaktent” for last. Because I can promise you won’t be able to sleep after you’ve read it. It reminds me of the time I was at an early screening of Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs and the projector broke. I escaped into the men’s room to discover Wes Craven at the next urinal. “I’m not going back in there,” he told me.

I couldn’t resist saying, “But, Wes, it’s only a movie.”

He shook his head. “I don’t care,” he told me. “It’s too damned real.”

Stuart Gordon20 June 2011

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrench’d

With a woful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale,

And then it set me free.

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told

This heart within me burns.

Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner.

I have heard it said, that, when any strange, supernatural, and necromantic adventure has occurred to a human being, that being, however desirous he may be to conceal the same, feels at certain periods torn up as it were by an intellectual earthquake, and is forced to bare the inner depths of his spirit to another. I am a witness of the truth of this. I have dearly sworn to myself never to reveal to human ears the horrors to which I once, in excess of fiendly pride, delivered myself over. The holy man who heard my confession, and reconciled me to the church, is dead. None knows that once—

Why should it not be thus? Why tell a tale of impious tempting of Providence, and soul-subduing humiliation? Why? answer me, ye who are wise in the secrets of human nature! I only know that so it is; and in spite of strong resolve – of a pride that too much masters me – of shame, and even of fear, so to render myself odious to my species – I must speak.

Genoa! my birth-place – proud city! looking upon the blue waves of the Mediterranean sea – dost thou remember me in my boyhood, when thy cliffs and promontories, thy bright sky and gay vineyards, were my world? Happy time! when to the young heart the narrow-bounded universe, which leaves, by its very limitation, free scope to the imagination, enchains our physical energies, and, sole period in our lives, innocence and enjoyment are united. Yet, who can look back to childhood, and not remember its sorrows and its harrowing fears? I was born with the most imperious, haughty, tameless spirit, with which ever mortal was gifted. I quailed before my father only; and he, generous and noble, but capricious and tyrannical, at once fostered and checked the wild impetuosity of my character, making obedience necessary, but inspiring no respect for the motives which guided his commands. To be a man, free, independent; or, in better words, insolent and domineering, was the hope and prayer of my rebel heart.

My father had one friend, a wealthy Genoese noble, who in a political tumult was suddenly sentenced to banishment, and his property confiscated. The Marchese Torella went into exile alone. Like my father, he was a widower: he had one child, the almost infant Juliet, who was left under my father’s guardianship. I should certainly have been an unkind master to the lovely girl, but that I was forced by my position to become her protector. A variety of childish incidents all tended to one point – to make Juliet see in me a rock of refuge; I in her, one who must perish through the soft sensibility of her nature too rudely visited, but for my guardian care. We grew up together. The opening rose in May was not more sweet than this dear girl. An irradiation of beauty was spread over her face. Her form, her step, her voice – my heart weeps even now, to think of all of relying, gentle, loving, and pure, that was enshrined in that celestial tenement. When I was eleven and Juliet eight years of age, a cousin of mine, much older than either – he seemed to us a man – took great notice of my playmate; he called her his bride, and asked her to marry him. She refused, and he insisted, drawing her unwillingly towards him. With the countenance and emotions of a maniac I threw myself on him – I strove to draw his sword – I clung to his neck with the ferocious resolve to strangle him: he was obliged to call for assistance to disengage himself from me. On that night I led Juliet to the chapel of our house: I made her touch the sacred relics – I harrowed her child’s heart, and profaned her child’s lips with an oath, that she would be mine, and mine only.

Well, those days passed away. Torella returned in a few years, and became wealthier and more prosperous than ever. When I was seventeen my father died; he had been magnificent to prodigality; Torella rejoiced that my minority would afford an opportunity for repairing my fortunes. Juliet and I had been affianced beside my father’s deathbed – Torella was to be a second parent to me.

I desired to see the world, and I was indulged. I went to Florence, to Rome, to Naples; thence I passed to Toulon, and at length reached what had long been the bourne of my wishes, Paris. There was wild work in Paris then. The poor king, Charles the Sixth, now sane, now mad, now a monarch, now an abject slave, was the very mockery of humanity. The queen, the dauphin, the Duke of Burgundy, alternately friends and foes now meeting in prodigal feasts, now shedding blood in rivalry, were blind to the miserable state of their country, and the dangers that impended over it, and gave themselves wholly up to dissolute enjoyment or savage strife. My character still followed me. I was arrogant and self-willed; I loved display, and above all, I threw all control far from me. Who could control me in Paris? My young friends were eager to foster passions which furnished them with pleasures. I was deemed handsome – I was master of every knightly accomplishment. I was disconnected with any political party. I grew a favourite with all: my presumption and arrogance were pardoned in one so young: I became a spoiled child. Who could control me? not the letters and advice of Torella – only strong necessity visiting me in the abhorred shape of an empty purse. But there were means to refill this void. Acre after acre, estate after estate, I sold. My dress, my jewels, my horses and their caparisons, were almost unrivalled in gorgeous Paris, while the lands of my inheritance passed into possession of others.

The Duke of Orleans was waylaid and murdered by the Duke of Burgundy. Fear and terror possessed all Paris. The dauphin and the queen shut themselves up; every pleasure was suspended. I grew weary of this state of things, and my heart yearned for my boyhood’s haunts. I was nearly a beggar, yet still I would go there, claim my bride, and rebuild my fortunes. A few happy ventures as a merchant would make me rich again. Nevertheless, I would not return in humble guise. My last act was to dispose of my remaining estate near Albaro for half its worth, for ready money. Then I despatched all kinds of artificers, arras, furniture of regal splendour, to fit up the last relic of my inheritance, my palace in Genoa. I lingered a little longer yet, ashamed at the part of the prodigal returned, which I feared I should play. I sent my horses. One matchless Spanish jennet I despatched to my promised bride; its caparisons flamed with jewels and cloth of gold. In every part I caused to be entwined the initials of Juliet and her Guido. My present found favour in hers and in her father’s eyes.

Still to return a proclaimed spendthrift, the mark of impertinent wonder, perhaps of scorn, and to encounter singly the reproaches or taunts of my fellow-citizens, was no alluring prospect. As a shield between me and censure, I invited some few of the most reckless of my comrades to accompany me: thus I went armed against the world, hiding a rankling feeling, half fear and half penitence, by bravado and an insolent display of satisfied vanity.

I arrived in Genoa. I trod the pavement of my ancestral palace. My proud step was no interpreter of my heart, for I deeply felt that, though surrounded by every luxury, I was a beggar. The first step I took in claiming Juliet must widely declare me such. I read contempt or pity in the looks of all. I fancied, so apt is conscience to imagine what it deserves, that rich and poor, young and old, all regarded me with derision. Torella came not near me. No wonder that my second father should expect a son’s deference from me in waiting first on him. But, galled and stung by a sense of my follies and demerit, I strove to throw the blame on others. We kept nightly orgies in Palazzo Carega. To sleepless, riotous nights, followed listless, supine mornings. At the Ave Maria we showed our dainty persons in the streets, scoffing at the sober citizens, casting insolent glances on the shrinking women. Juliet was not among them – no, no; if she had been there, shame would have driven me away, if love had not brought me to her feet.

I grew tired of this. Suddenly I paid the Marchese a visit. He was at his villa, one among the many which deck the suburb of San Pietro d’Arena. It was the month of May – a month of May in that garden of the world, the blossoms of the fruit trees were fading among thick, green foliage; the vines were shooting forth; the ground strewed with the fallen olive blooms; the firefly was in the myrtle hedge; heaven and earth wore a mantle of surpassing beauty. Torella welcomed me kindly, though seriously; and even his shade of displeasure soon wore away. Some resemblance to my father – some look and tone of youthful ingenuousness, lurking still in spite of my misdeeds, softened the good old man’s heart. He sent for his daughter – he presented me to her as her betrothed. The chamber became hallowed by a holy light as she entered. Hers was that cherub look, those large, soft eyes, full dimpled cheeks, and mouth of infantine sweetness, that expresses the rare union of happiness and love. Admiration first possessed me; she is mine! was the second proud emotion, and my lips curled with haughty triumph. I had not been the enfant gâté of the beauties of France not to have learnt the art of pleasing the soft heart of woman. If towards men I was overbearing, the deference I paid to them was the more in contrast. I commenced my courtship by the display of a thousand gallantries to Juliet, who, vowed to me from infancy, had never admitted the devotion of others; and who, though accustomed to expressions of admiration, was uninitiated in the language of lovers.

For a few days all went well. Torella never alluded to my extravagance; he treated me as a favourite son. But the time came, as we discussed the preliminaries to my union with his daughter, when this fair face of things should be overcast. A contract had been drawn up in my father’s lifetime. I had rendered this, in fact, void, by having squandered the whole of the wealth which was to have been shared by Juliet and myself. Torella, in consequence, chose to consider this bond as cancelled, and proposed another, in which, though the wealth he bestowed was immeasurably increased, there were so many restrictions as to the mode of spending it, that I, who saw independence only in free career being given to my own imperious will, taunted him as taking advantage of my situation, and refused utterly to subscribe to his conditions. The old man mildly strove to recall me to reason. Roused pride became the tyrant of my thought: I listened with indignation – I repelled him with disdain.

“Juliet, thou art mine! Did we not interchange vows in our innocent childhood? are we not one in the sight of God? and shall thy cold-hearted, cold-blooded father divide us? Be generous, my love, be just; take not away a gift, last treasure of thy Guido – retract not thy vows – let us defy the world, and setting at nought the calculations of age, find in our mutual affection a refuge from every ill.”

Fiend I must have been, with such sophistry to endeavour to poison that sanctuary of holy thought and tender love. Juliet shrank from me affrighted. Her father was the best and kindest of men, and she strove to show me how, in obeying him, every good would follow. He would receive my tardy submission with warm affection; and generous pardon would follow my repentance. Profitless words for a young and gentle daughter to use to a man accustomed to make his will, law; and to feel in his own heart a despot so terrible and stern, that he could yield obedience to nought save his own imperious desires! My resentment grew with resistance; my wild companions were ready to add fuel to the flame. We laid a plan to carry off Juliet. At first it appeared to be crowned with success. Midway, on our return, we were overtaken by the agonized father and his attendants. A conflict ensued. Before the city guard came to decide the victory in favour of our antagonists, two of Torella’s servitors were dangerously wounded.

This portion of my history weighs most heavily with me. Changed man as I am, I abhor myself in the recollection. May none who hear this tale ever have felt as I. A horse driven to fury by a rider armed with barbed spurs, was not more a slave than I, to the violent tyranny of my temper. A fiend possessed my soul, irritating it to madness. I felt the voice of conscience within me; but if I yielded to it for a brief interval, it was only to be a moment after torn, as by a whirlwind, away – borne along on the stream of desperate rage – the plaything of the storms engendered by pride. I was imprisoned, and, at the instance of Torella, set free. Again I returned to carry off both him and his child to France; which hapless country, then preyed on by freebooters and gangs of lawless soldiery, offered a grateful refuge to a criminal like me. Our plots were discovered. I was sentenced to banishment; and, as my debts were already enormous, my remaining property was put in the hands of commissioners for their payment. Torella again offered his mediation, requiring only my promise not to renew my abortive attempts on himself and his daughter. I spurned his offers, and fancied that I triumphed when I was thrust out from Genoa, a solitary and penniless exile. My companions were gone: they had been dismissed the city some weeks before, and were already in France. I was alone – friendless; with no sword at my side, nor ducat in my purse.

I wandered along the sea-shore, a whirlwind of passion possessing and tearing my soul. It was as if a live coal had been set burning in my breast. At first I meditated on what I should do. I would join a band of freebooters. Revenge! – the word seemed balm to me: – I hugged it – caressed it – till, like a serpent, it stung me. Then again I would abjure and despise Genoa, that little corner of the world. I would return to Paris, where so many of my friends swarmed; where my services would be eagerly accepted; where I would carve out fortune with my sword, and might, through success, make my paltry birth-place, and the false Torella, rue the day when they drove me, a new Coriolanus, from her walls. I would return to Paris – thus, on foot – a beggar – and present myself in my poverty to those I had formerly entertained sumptuously? There was gall in the mere thought of it.

The reality of things began to dawn upon my mind, bringing despair in its train. For several months I had been a prisoner: the evils of my dungeon had whipped my soul to madness, but they had subdued my corporeal frame. I was weak and wan.

Torella had used a thousand artifices to administer to my comfort; I had detected and scorned them all – and I reaped the harvest of my obduracy. What was to be done? Should I crouch before my foe, and sue for forgiveness? – Die rather ten thousand deaths! – Never should they obtain that victory! Hate – I swore eternal hate! Hate from whom? – to whom? – From a wandering outcast to a mighty noble. I and my feelings were nothing to them: already had they forgotten one so unworthy. And Juliet! – her angel-face and sylphlike form gleamed among the clouds of my despair with vain beauty; for I had lost her – the glory and flower of the world! Another will call her his! – that smile of paradise will bless another!

Even now my heart fails within me when I recur to this rout of grim-visaged ideas. Now subdued almost to tears, now raving in my agony, still I wandered along the rocky shore, which grew at each step wilder and more desolate. Hanging rocks and hoar precipices overlooked the tideless ocean; black caverns yawned; and for ever, among the seaworn recesses, murmured and dashed the unfruitful waters. Now my way was almost barred by an abrupt promontory, now rendered nearly impracticable by fragments fallen from the cliff. Evening was at hand, when, seaward, arose, as if on the waving of a wizard’s wand, a murky web of clouds, blotting the late azure sky, and darkening and disturbing the till now placid deep. The clouds had strange fantastic shapes; and they changed, and mingled, and seemed to be driven about by a mighty spell. The waves raised their white crests; the thunder first muttered, then roared from across the waste of waters, which took a deep purple dye, flecked with foam. The spot where I stood, looked, on one side, to the wide-spread ocean; on the other, it was barred by a rugged promontory. Round this cape suddenly came, driven by the wind, a vessel. In vain the mariners tried to force a path for her to the open sea – the gale drove her on the rocks. It will perish! – all on board will perish! – Would I were among them! And to my young heart the idea of death came for the first time blended with that of joy. It was an awful sight to behold that vessel struggling with her fate. Hardly could I discern the sailors, but I heard them. It was soon all over! – A rock, just covered by the tossing waves, and so unperceived, lay in wait for its prey. A crash of thunder broke over my head at the moment that, with a frightful shock, the skiff dashed upon her unseen enemy. In a brief space of time she went to pieces. There I stood in safety; and there were my fellow-creatures, battling, how hopelessly, with annihilation. Methought I saw them struggling – too truly did I hear their shrieks, conquering the barking surges in their shrill agony. The dark breakers threw hither and thither the fragments of the wreck: soon it disappeared. I had been fascinated to gaze till the end: at last I sank on my knees – I covered my face with my hands: I again looked up; something was floating on the billows towards the shore. It neared and neared. Was that a human form? – It grew more distinct; and at last a mighty wave, lifting the whole freight, lodged it upon a rock. A human being bestriding a sea-chest! – A human being! – Yet was it one? Surely never such had existed before – a misshapen dwarf, with squinting eyes, distorted features, a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...