- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

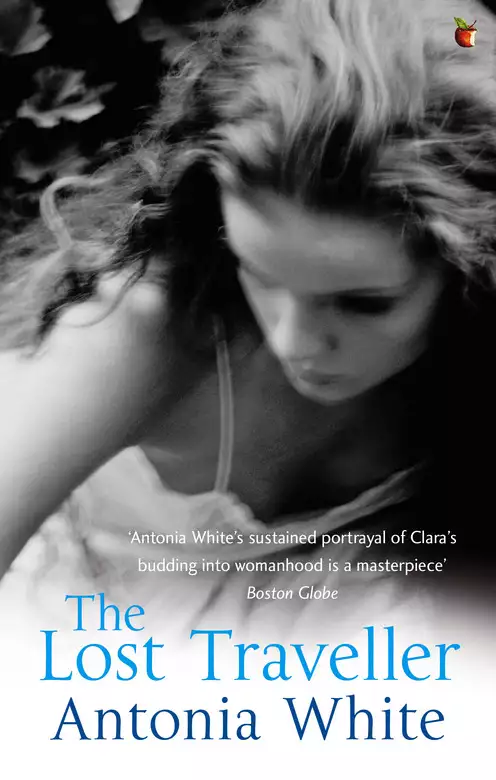

When Clara returns home from the convent of her childhood to begin life at a local girls' school, she is at a loss: although she has comparative freedom, she misses the discipline the nuns imposed and worries about keeping her faith in a secular world. Against the background of the First World War, Clara experiences the confusions of adolescence - its promise, its threat of change. She longs for love, yet fears it, and wonders what the future will hold. Then tragedy strikes and her childhood haltingly comes to an end as she realises that neither parents nor her faith can help her.

The Lost Traveller is the first in the trilogy sequel to Frost in May, which continues with The Sugar House and Beyond the Glass. Although each is a complete novel in itself, together they form a brilliant portrait of a young girl's journey to adulthood.

Release date: February 17, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lost Traveller

Antonia White

three books – The Lost Traveller, The Sugar House and Beyond the Glass – which complete the story she began in her famous novel Frost in May. Now eighty years of age, and a novelist whose small output reflects the virulent writer’s block which has constantly interrupted

her writing life, she preferred to talk to me. For though separated by age, country of birth and nationality, we share a Catholic

upbringing which has been a dominant influence on both our lives. What follows is based on a long conversation I had with

Antonia White in December 1978, and on the many times we’ve talked since Virago first re-published Frost in May earlier that year.

‘Personal novels,’ wrote Elizabeth Bowen in a review of Antonia White’s work, ‘those which are obviously based on life, have

their own advantages and hazards. But we have one “personal” novelist who has brought it off infallibly.’ Antonia White turned

fact into fiction in a quartet of novels based on her life from the ages of nine to twenty-three. ‘My life is the raw material

for the novels, but writing an autobiography and writing fiction are very different things.’ This transformation of real life

into an imagined work of art is perhaps her greatest skill as a novelist.

Antonia White was the only daughter of Cecil Botting, Senior Classics Master at St Paul’s School, who became a Catholic at

the age of thirty-five, taking with him into the Church his wife and seven-year-old daughter, fictionalized as ‘Nanda’ in Frost in May. This novel is a brilliant portrait of Nanda’s experiences in the enclosed world of a Catholic convent. First published in

1933, it was immediately recognized as a classic. Antonia White wrote what was to become the first two chapters of Frost in May when she was only sixteen, completing it sixteen years later, in 1931. At the time she was married to Tom Hopkinson, writer,

journalist and later editor of Picture Post.

‘I’d written one or two short stories, but really I wrote nothing until after my father’s death in 1929. At the time I was

doing a penitential stint in Harrods Advertising Agency … I’d been sacked from Crawfords in 1930 for not taking a passionate

enough interest in advertising. One day I was looking through my desk and I came across this bundle of manuscript. Out of

curiosity I begin to read it and some of the things in it made me laugh. Tom asked me to read it to him, which I did, and

then he said, ‘You must finish it.’ Anyway Tom had appendicitis and we were very hard up, so I was working full time. But

Tom insisted I finish a chapter every Saturday night. Somehow or other I managed to do it, and then Tom thought I should send

it to the publisher – Cobden Sanderson – who’d liked my short stories. They wrote back saying it was too slight to be of interest

to anyone. Several other people turned it down and then a woman I knew told me that Desmond Harmsworth had won some money

in the Irish sweep and didn’t know what to do with it … so he started a publishing business and in fact I think Frost in May was the only thing he ever published … it got wonderful reviews.’

Between 1933 and 1950 Antonia White wrote no more novels. She was divorced from Tom Hopkinson in 1938, worked in advertising,

for newspapers, as a freelance journalist and then came the war. Throughout this period she suffered further attacks of the

mental illness she first experienced in 1922. This madness Antonia White refers to as ‘The Beast’ – Henry James’ ‘Beast in

the Jungle’. Its recurrence and a long period of psychoanalysis interrupted these years.

‘I’d always wanted to write another novel, having done one, but then you see the 1930s were a very difficult time for me because

I started going off my head again. After the war and the political work I did I was terribly hard up. Then Enid Starkey, whom

I’d met during the war, suggested to Hamish Hamilton that I should have a shot at translating and they liked what I did. After

that I got all these commissions and I was doing two or three a year but I was completely jammed up on anything of my own,

though I kept on trying to write in spite of it. I always wanted to write another novel, and I wanted this time to do something

more ambitious, what I thought would be a ‘proper’ novel, not seen only through the eyes of one person as it is in Frost in May, but through the eyes of her father, her mother and even those old great-aunts in the country. Then suddenly I could write

again. The first one [The Lost Traveller] took the longest to write. I don’t know how many years it took me, but I was amazed how I then managed to write the other

two [ The Sugar House and Beyond the Glass]. They came incredibly quickly.’

In 1950, seventeen years after the publication of Frost in May, The Lost Traveller was published. In it Antonia White changed the name of her heroine Nanda Grey to Clara Batchelor. ‘Of course Clara is a continuation

of Nanda. Nanda became Clara because my father had a great passion for Meredith and a particular passion for Clara Middleton

(heroine of The Egoist). Everything that happened to Clara in The Lost Traveller is the sort of thing that happened to me, though many things are changed, many invented. I wanted The Lost Traveller to be a real novel – Frost in May was so much my own life. So I changed her name …’ In every other respect this novel begins where Frost in May ends. It is a vivid account of adolescence, of the mutual relationships of father, mother and daughter as Clara grows to

maturity and comes to grips with the adult world.

Two years later Antonia White continued Clara’s story, in The Sugar House.

Carmen Callil, Virago, London, 1979

Antonia White died on 10th April, 1980

On every ordinary weekday in term-time, Claude Batchelor stepped out of his house at exactly twenty minutes past nine, slammed

the door and set off at a furious pace in the direction of St Mark’s School. People who lived in certain West Kensington streets

timed their watches by the sturdy, immaculately dressed figure which hurried past their windows as punctually as a train.

But on a certain Tuesday in March 1914 it was well after eleven when Claude Batchelor left his house. He shut the door softly

behind him and stood hesitating on the steps as if he could not decide which way to go.

He was as carefully dressed and shaved as usual but his blue eyes were bloodshot and his clear skin dulled to a greyish yellow.

His was one of those faces that suffering caricatures. The firm, fleshy features, Saxon in colouring, late Roman in cast,

were trained to express humour and anger; under the stress of grief they merely looked dissipated.

For three years Claude had known that his father might die at any time. He had accustomed himself to say to his wife, ‘We

must realize that my father cannot live indefinitely’ and even ‘When my father dies, we might do so-and-so.’ Now that his

father was dead, he knew that never for one moment had the idea been real to him.

Certainly he had behaved as he had always intended to behave. Ever since the nurse had said ‘Poor man, he really has gone

now’ and competently closed his father’s eyes, Claude had done everything expected of him. For the past few hours he had been calming

and directing with stoical efficiency, making neat lists of what must be done and who must be informed. Now, standing alone

in front of the shrouded house, his will collapsed. It cost him a huge effort to remind himself why he had come out and to

order his legs to carry him in the right direction.

By the time he reached the post office he had recovered enough mechanical awareness to write out several telegrams. His small

upright hand, the writing of a man who constantly uses Greek characters, was as lucid as usual but his mind was still clouded.

When he came out into the street again, the spring sunshine seemed as unnatural as the electric light and drawn blinds he

had left at home and people as remote as figures on a stage. North End Road was filling up with the miscellaneous crowd that

took possession of it when the city men had gone to work and the two great schools drawn in their population. It was the hour

when the young actresses, with smears of last night’s make-up still on their eyelids, sauntered out to have their hair waved

or to exercise their little dogs; when the old actors, pretending they were on their way to rehearsal, converged in the direction

of the ‘Three Kings’. Wives were doing their shopping, frowning over their lists and demanding that the joint or the whiting

be sent ‘in time for lunch, without fail, please’. Girls, newly grown-up and taking tiny self-conscious steps in tight skirts

that clung to their black silk ankles, were staring into drapers’ windows or ordering cakes for their mother’s bridge parties.

Perhaps because from now on there would be only women in his home he looked at the actors and the yellow-faced men retired

from the East almost wistfully. Had his sense of fitness not been so strong, he would have crossed over to the ‘Three Kings’

and, leaning on a counter spotted with wet rings, unloaded his misery on a stranger. Instead he stood by the pillar-box, clutching

his bundle of black-edged letters and staring. His jaw, which he had consciously thrust forward for so many years that it

was now underhung, dropped open as it used to do when he was a boy. The blow had momentarily cracked the shell of Claude Batchelor

the successful schoolmaster and exposed a long-forgotten Claude, dreamy, uncertain and awkward. Standing there on the pavement he lost for a time, as

in childhood, the sense of separate existence. Nothing marked him off from the girl staring into the hatshop window, the man

leering at her, the errand boy on the green bicycle, the old woman stuffing a cabbage into her string bag. He was so merged

in them that he knew when a head would turn or a foot falter. Suddenly he was touched by an old fear of which he had never

spoken to anyone, the fear that one day he might lose all control of his mind. Against that there was only one weapon: his

obstinate will. With all his might he called it into play, holding his breath as if forcing himself into a tight jacket. Then

he shot his letters in the box, clenched his teeth and set off at his usual quick pace towards home.

Valetta Road was one of the older streets of West Kensington. Built of stucco and sparrow-coloured brick, it was modelled

on the plan of more ambitious neighbourhoods but the houses were so narrow that they looked overloaded by their pillars and

balconies. Along the tops of either row ran a balustrade decorated at intervals with spiked urns shaped like policemen’s helmets.

Each house owned a pillar and a half so that when occasionally a tenant repainted his stucco, it produced an odd piebald effect.

No two façades were the same colour but showed greys, biscuits, ochres and hot browns in various stages of dinginess.

Sixteen years earlier, when Claude had come to live in Valetta Road, it had been one of the ‘best’ streets. Now, though it

was going downhill and he could well afford to move, he stayed on from habit and a kind of loyalty. Several houses still had

well-cleaned steps and shining brass and were inhabited by a single family. But, year by year, one or two more sank to the

degradation of a blistered front door flanked by three or four bells with a buckled card beside each. In summer there appeared

on the balconies of such houses people of whom the permanent inhabitants disapproved: young men who played banjoes; Indian

students and girls who sat about in flowered kimonos drying their hair in the sun and calling ‘Coo-ee’ to their friends in

the street.

Among the long-term tenants were men who worked in the city, doctors, army coaches and retired civil servants. The houses of all these were arranged, as if by agreement, on exactly the

same pattern. The ground-floor windows had curtains of heavy dark material, the first floor blue or rose brocade and white

lace draperies and the second floor casement cloth or chintz. If the blinds of Number 18 had not been drawn, its curtains

would have appeared perfectly correct except for those of the top-floor bedroom. These were of pink satin and people who disapproved

of Claude Batchelor’s wife saw in them one more proof of her extravagance and oddness.

Usually the whole household knew when its master arrived home. Claude’s key grated loudly in the lock, the door banged and

the clatter of his stick, as he rammed it into the pottery stand, reverberated on every floor. But today he came in as noiselessly

as he had gone out. Isabel, his wife, who was sewing in the darkened dining-room that opened off the hall, gave a little shriek

when he appeared in the doorway.

‘Claude! I didn’t know you were in the house.’

‘I’m sorry if I startled you.’

His voice, harsh with exhaustion, sounded angry rather than apologetic. The dimness was soothing to his eyes after the glare

of the street. A single cone of light fell on the table where Isabel sat, removing a crimson feather from a black velvet hat;

beyond its radius everything seemed blurred in fog. He remained in the shadow on the far side of the table, looking down at

her.

‘All the essential telegrams have gone,’ he said. ‘I shall send others as soon as we know the exact arrangements for the funeral.’

‘So efficient even today,’ she sighed. Then, more alertly, but without looking at him, she asked,

‘What have you done about Clara?’

‘I asked the Reverend Mother to send her home at once. Presumably she will arrive during the afternoon.’

Isabel raised her great eyes and stared at him.

‘Oh.’

‘Why that voice, my dear?’

‘You never told me you’d decided.’

Her face, unlike his, was perfectly designed to express tragedy. Even when she was gay, the slight droop of her mouth and her large brown exposed eyes gave her an air of sadness. Her soft,

stricken voice and the look that matched it accused him, as so often before, of being insensitive.

‘I took it for granted you would want her to be there.’

‘Poor little Clara,’ she wailed. ‘It seems so dreadful … a child at a funeral.’

‘Nearly fifteen is hardly a child, surely.’

‘Your mother’s idea, I suppose.’

He showed that he was hurt by thrusting out his jaw and speaking in his classroom tone.

‘As it happens, I did not consult my mother. I assumed … rashly it appears … that you would agree with me.’

Isabel made a few vague snips at her feather.

‘Of course, if you’ve made up your mind, there’s no point in my saying anything. Though how you can expose a little girl to

all these horrors …’

‘What exactly do you mean by horrors?’

She dropped her hands in her lap and shut her eyes.

‘Really, Claude. Today of all days I didn’t think you’d bully me.’

‘Bully you? Oh, my God!’ he said wearily.

‘Or swear at me.’ It was hardly more than a whisper. Her eyes remained closed.

He looked at her in silence. Once again she had defeated him. From his boyhood to this day his natural preference had always

been for golden-haired women; plump, good-tempered and insipidly pretty. Yet the moment he had set eyes, twenty years ago,

on a sallow, brown-haired girl whose beauty was only one degree removed from ugliness he had been fascinated, and fascinated

he remained. The sickly light exposed her face to him now wan and lifeless. Her hair, carelessly done, hung limply, revealing

the babyish, undeveloped forehead and eyebrows so faint as to be nearly invisible. The smooth arched eyelids were beginning

to wrinkle; the perfect lips, pale today and slackly parted as if in sleep, showed teeth that were even but no longer white.

The curves of cheek and jaw were still intact but the skin which had once had the satin texture of her arms now showed a roughened grain to which drifts of powder clung unevenly. He was reminded of a gardenia, just turning

brown at the edges, its perfume intensified by the first touch of decay. His anger melted into resentful tenderness.

Feeling his eyes on her, she slowly opened her own and her soft high voice was no longer aggrieved as she lisped:

‘What do I mean by horrors, dea’est? You’ve only to look round this room.’

The room was sombre enough at any time with its dark red walls and greenish-brown curtains. Today it was muffled in black

draperies which blotted up the weak light. Black garments trailed everywhere over the chairs; even the mirror over the fireplace

was swathed in a black shawl.

‘When a family is in mourning, one expects this, surely.’

‘Not in all families, Claude. My father insisted we weren’t to wear black even at his funeral.’

‘Your father, my dear, as you have repeatedly told me, was a highly unconventional man.’

‘I don’t see why we should have to go to the other extreme. I doubt if anyone draws the blinds down now except in the East

End.’

‘My mother would be upset if we didn’t.’

‘Your mother again. Of course, what I want counts for nothing in this house.’

‘Isabel, be reasonable. Can’t you just for once …?’

She ignored him.

‘Your father would have agreed with me,’ she persisted. ‘He had all the right instincts, dear old man.’

Usually any praise of his father, however patronizing, softened Claude at once. However, he said nothing and, glancing at

him, Isabel saw that his face was set. She said coaxingly,

‘I think it’s a beautiful idea of yours to have him buried at Rookfield.’

‘I’m glad you approve. I only hope that the sight of so many of my relatives won’t be too much for you.’

She began to pluck once more at the feather with the uncertain movements of a woman who seldom uses her hands.

‘Really, Claude, is it my fault if ugliness of any kind jars on me so dreadfully? I hope for her own sake that Clara isn’t

as sensitive as I am.’

‘I’m quite certain she isn’t. As you often say, she takes after my family.’

Isabel pushed her hat away and stared into space.

‘Father always thought I was born with a skin too few. I daresay it’s literally true.’

‘My dear, no one attempts to compete with you in the finer feelings. No doubt I myself was born with several skins too many.’

‘Claude, how can you be so cruel and sarcastic today of all days? Don’t you realize how all this brings things back to me?

You seem to forget that I lost my father too. Oh, I know it’s fifteen years ago. But it seems like yesterday.’

Once more she had beaten him. In sign of surrender he crossed the room and sat down beside her.

‘I’m sorry, Isabel. I’m shockingly irritable this morning.’

She turned her eyes vaguely in his direction, looking at a point somewhere over his shoulder.

‘I know it’s dreadful for you, Claude. I can sympathize. But at least you were prepared.’

He said blankly,

‘Oh yes. I was prepared.’

‘I had no warning. We hadn’t the faintest idea that he had a weak heart. Yet that morning when the telegram came I knew at

once that it was Father. I’ve often wondered if I’m not a little psychic.’

‘Very possibly.’

‘You, Claude, at least still have a mother. Just think, I can’t even remember mine. I was only three months old when she died.’

She had told him these things many times before in almost identical words. When she did so her eyes always became fixed and

she spoke in a high faint monotone. With exasperated tenderness, he took her hand. She yielded it vaguely and the needle she

was holding pricked his finger. At the sight of the blood she started and cried out too late,

‘Oh, dea’est, be careful.’

She made a little grimace as he dabbed his bleeding finger. Then suddenly she smiled.

‘Do you remember? When we were engaged. The pin in my belt. You were so furious because you thought it was untidy of me to

have a pin in my belt at all. But the next day you sent me a poem in Latin all about the thorny rose.’

He did remember, as if from another life, Isabel with her hair in soft puffs and wearing a pink blouse, standing under a lilac

tree in her father’s garden.

‘You had to translate it for me,’ she went on. ‘I was so proud of having a poem written to me in Latin and so ashamed not

to be able to make out a single word except “Rosa”. Such a foolish Belle. And then you did try to teach me Latin and had to

give me up as hopeless. I’ve often wondered why, because my French is so good.’

‘You can’t teach when you’re in love with your pupil.’

‘Then I hope I was your only failure.’

He had to smile.

‘Positively my only failure.’

‘All the same, I expect you’d have been much happier if you’d married a female don or something.’

‘Heaven forbid!’

‘You and Clara between you sometimes make me feel a complete idiot. If one of your pupils sent Clara a love poem in Latin,

she’d be able to understand every word, wouldn’t she?’

His face stiffened again.

‘If any of my pupils had the impertinence …’ he began fiercely.

She interrupted,

‘Yet you were just saying that she wasn’t a child any more.’

‘From that point of view, the longer we think of her as a child the better.’

‘You needn’t worry. I daresay you’ll make Clara so learned that no young man will ever dare come near her.’ She frowned. ‘No

one ever asked me if I wanted my pretty daughter turned into a blue-stocking.’

‘The child has good brains. Why shouldn’t she use them? Apart from the fact that she will almost certainly have to make her

own living.’

‘I still think it was overdoing it to make her puzzle over declensions and things when she was seven.’

‘She enjoyed it.’ His face cleared. ‘Ah, at that age she was a joy to teach.’

‘Isn’t she now?’ said Isabel innocently. ‘She’s always so desperately anxious to please you.’

Again he frowned.

‘Hmm. I wonder. When she was younger, yes. But now … this last year or two … I wonder.’

‘More than ever now, Claude. I’m in a very good position to judge.’ She snapped her fingers. ‘For ages I haven’t counted that with Clara.’

He thrust his jaw forward.

‘If I thought that were true, Isabel, I should have to speak to her. And in no uncertain terms.’

‘Please don’t, dearest. Certainly not today when she’s just had such a shock. I daresay all clever daughters are critical

of their Mammas at her age. Yet when I think how I used to long for a mother when I was beginning to grow up! But I wasn’t

a bit like Clara. I was such an absurd romantic little thing, living in a sort of fairy-tale world of my own.’

‘I’m by no means satisfied with Clara myself,’ said Claude. ‘It seems to me that lately the child has become hard and self-centred.’

‘Yet she was so sweet and affectionate when she was tiny, wasn’t she? I can see her now in her big white bonnet, trotting

along beside her Grandfather, holding his hand and looking up at him so adoringly.’

‘Ah,’ he sighed. ‘If we could go back to those years!’

She touched his hand lightly.

‘Poor Claude. I was almost forgetting. I’m sure no one will miss him more than I shall.’

‘He was so fond of you, Isabel.’

‘Wasn’t it touching, the way he took such an interest in my clothes and so on? He really had quite a flair for such things.

It’s strange when you think of …’

She broke off in time and he, knowing perfectly well what she had been about to say, made no comment. To cover it, she gave the feather a tug and it came away with a crackle of ripped

stitches.

‘There, now I’ve deliberately ruined his favourite hat. He would have been the first to see it’s nothing without the feather.’

‘I think he would have been touched by your sacrificing it.’

‘What good can it do him, poor dear? I think there’s something positively unchristian in all this gloomy attitude to death.

After all, we are supposed to believe he’s gone to a happier place.’

He half smiled.

‘As Catholics, we usually expect a certain delay.’

‘You mean purgatory and all that? I think purgatory’s a wonderful idea. So consoling for people like me. And so logical when

you come to think of it. All the same, in the East they wear flowers at funerals and make quite a festival of the whole thing.’

‘I’ve no idea what they do in the East.’

Isabel stroked her cheek with the crimson feather and said dreamily,

‘If I died first, you’d have to make all the arrangements for my funeral, wouldn’t you, Claude?’

She ignored his ‘Dear girl … for heaven’s sake!’ and went on:

‘I should like everyone to wear their nicest clothes. And no funeral march. Just that Chopin nocturne I used to play you when

we were engaged. And don’t give me a tombstone. I should feel crushed under it. I’d like you to plant a rose bush and a cypress

tree on my grave.’

‘Will you kindly stop, Isabel.’

She looked at him with a childish wonder that might or might not have been simulated.

‘I’ve always prayed,’ he said, ‘that you would outlive me.’

‘Isn’t that rather selfish, dearest? It’s so much worse for the one who is left.’

‘Of course it is selfish,’ he said angrily, suddenly pulling her close to him.

‘There was a knock at the door and they quickly composed their faces and attitudes. Zillah the housemaid came in, carrying

an enormous cardboard box. She wore her black afternoon uniform instead of her morning print and her handsome grey eyes were

swollen.

‘Mr Shapiro’s chauffeur left this for you, Sir.’

‘Even the servants loved him,’ Claude said when the girl had gone. ‘Poor Zillah was in tears this morning.’

‘Servants love deaths and funerals. Even a pretty girl like Zillah doesn’t get much excitement in her life.’

Claude methodically untied the box. From layers of tissue paper, there emerged an immense wreath of lilies of the valley and

mauve cattleyas.

‘Oh, how exquisite,’ said Isabel, staring greedily.

Claude’s eyes filled.

‘If only he could see them!’

‘When we’re alive,’ said Isabel, ‘no one thinks of sending us orchids. All the time he was ill, Becky Shapiro never sent him

so much as a bunch of violets.’

‘Really, it is too much. They shouldn’t have done it.’

‘Why? It’s nothing to these rich Jews.’

‘Plenty of rich Christians wouldn’t even have thought of it,’ he said sharply.

‘The Shapiros owe it you. Look at all you’ve done for their little Izzy and their little Sam. All right, my dear, I admit

it is nice of them. But I can never help smiling when I think of those boys, born over a fried-fish shop, going to Oxford.’

‘Is it any odder than my sending Clara to Mount Hilary? Why shouldn’t the Shapiros want things for their children that they

haven’t had themselves?’

It was her turn to stiffen.

‘You seem to forget,’ she said coldly, ‘that Clara is half a Maule. If my grandfather hadn’t lost his money, if my father

hadn’t been eccentric and cut himself off from society …’

‘Yes, yes, my dear,’ he said hastily to avert what must inevitably come next: the Maule coat of arms; the Lawrence portraits;

the snuffbox presented by George III. ‘No one realizes it better than I. And no one is gladder for Clara’s sake.’

Easily propitiated, she smiled.

‘It’s the only trace,’ she said. ‘Your being so impressed by money and the Shapiro kind of vulgar success.’

‘I like Shapiro for himself.’

‘You always say he’s very intelligent. He certainly plays an extraordinary game of bridge. But I can’t get over that accent

and those fingers.’

She stroked her nose appreciatively with her own impeccable hand. The nose too was impeccable: straight and thin, with finely

incised nostrils.

‘Such a pity about Clara’s nose,’ she said. ‘You couldn’t call it ugly but it has definitely spread a trifle.’

Her eyes wandered again to the flowers.

‘Lovely, lovely things. Doesn’t it seem criminal to think

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...