- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

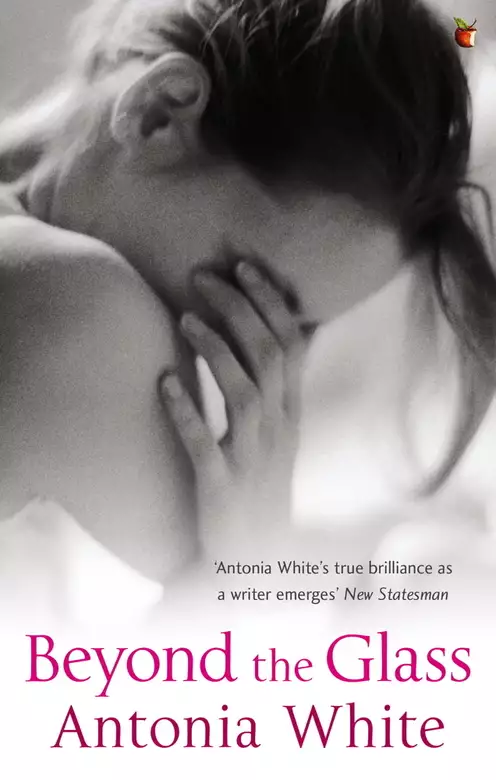

Clara Batchelor is twenty-two. Her brief, doomed marriage to Archie over, she returns to live with her parents in the home of her childhood. She hopes for comfort but the devoutly Catholic household confines her and forms a dangerous glass wall of guilt and repression between Clara and the outside world. Clara both longs for and fears what lies beyond, and when she escapes into an exhilarating and passionate love affair her fragile identity cracks. Beyond the Glass completes the trilogy sequel to Frost in May, which began with The Lost Traveller and The Sugar House. Although each is a complete novel in itself, together they form a brilliant portrait of a young girl's journey to adulthood.

Release date: February 3, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Beyond The Glass

Antonia White

three books – The Lost Traveller, The Sugar House and Beyond the Glass – which complete the story she began in her famous novel Frost in May. Now eighty years of age, and a novelist whose small output reflects the virulent writer’s block which has constantly interrupted

her writing life, she preferred to talk to me. For though separated by age, country of birth and nationality, we share a Catholic

upbringing which has been a dominant influence on both our lives. What follows is based on a long conversation I had with

Antonia White in December 1978, and on the many times we’ve talked since Virago first re-published Frost in May earlier that year.

‘Personal novels,’ wrote Elizabeth Bowen in a review of Antonia White’s work, ‘those which are obviously based on life, have

their own advantages and hazards. But we have one “personal” novelist who has brought it off infallibly.’ Antonia White turned

fact into fiction in a quartet of novels based on her life from the ages of nine to twenty-three. ‘My life is the raw material

for the novels, but writing an autobiography and writing fiction are very different things.’ This transformation of real life

into an imagined work of art is perhaps her greatest skill as a novelist.

Antonia White was the only child of Cecil Botting, Senior Classics Master at St Paul’s School, who became a Catholic at the age of thirty-five taking with him into the Church his

wife and seven-year-old daughter, fictionalised as ‘Nanda’ in Frost in May. This novel is a brilliant portrait of Nanda’s experiences in the enclosed world of a Catholic convent. First published in

1933, it was immediately recognized as a classic. Antonia White wrote what was to become the first two chapters of Frost in May when she was only sixteen, completing it sixteen years later, in 1931. At the time she was married to Tom Hopkinson, writer,

journalist and later editor of Picture Post.

‘I’d written one or two short stories, but really I wrote nothing until my father’s death in 1929. I’d worked in advertising

all those years, as a copywriter, and I’d done articles for women’s pages and all sorts of women’s magazines, but I couldn’t

bring myself to write anything serious until after my father died. At the time I was doing a penitential stint in Harrods’

Advertising Department … I’d been sacked from Crawfords in 1930 for not taking a passionate enough interest in advertising.

One day I was looking through my desk and I came across this bundle of manuscript. Out of curiosity I began to read it and

some of the things in it made me laugh. Tom asked me to read it to him, which I did, and then he said “You must finish it.”

Anyway Tom had appendicitis and we were very hard up, so I was working full time. But Tom insisted I finish a chapter every

Saturday night. Somehow or other I managed to do it, and then Tom thought I should send it to the publisher – Cobden Sanderson

– who’d liked my short stories. They wrote back saying it was too slight to be of interest to anyone. Several other people

turned it down and then a woman I knew told me that Desmond Harmsworth had won some money in the Irish sweep and didn’t know

what to do with it … so he started a publishing business and in fact I think Frost in May was the only thing he ever published … it got wonderful reviews.’

Between 1933 and 1950 Antonia White wrote no more novels. She was divorced from Tom Hopkinson in 1938, worked in advertising,

for newspapers, as a freelance journalist and then came the war. Throughout this period she suffered further attacks of the mental illness she first experienced in 1922. This madness Antonia White refers to as ‘The Beast’ – Henry James’ ‘Beast in

the Jungle’. Its recurrence and a long period of psychoanalysis interrupted these years.

‘I’d always wanted to write another novel, having done one, but then you see the 1930s were a very difficult time for me because

I started going off my head again. After the war and the political work I did I was terribly hard up. Then Enid Starkey, whom

I’d met during the war, suggested to Hamish Hamilton that I should have a shot at translating and they liked what I did. After

that I got all these commissions and I was doing two or three a year but I was completely jammed up on anything of my own,

though I kept on trying to write in spite of it. I always wanted to write another novel, and I wanted this time to do something

more ambitious, what I thought would be a “proper” novel, not seen only through the eyes of one person as it is in Frost in May, but through the eyes of the father, the mother and even those old great aunts in the country. Then suddenly I could write

again. The first one [The Lost Traveller] took the longest to write. I don’t know how many years it took me, but I was amazed how I then managed to write the other

two [The Sugar House and Beyond the Glass]. They came incredibly quickly.’

In 1950, seventeen years after the publication of Frost in May, The Lost Traveller was published. In it Antonia White changed the name of her heroine Nanda Grey to Clara Batchelor. ‘Of course Clara is a continuation

of Nanda. Nanda became Clara because my father had a great passion for Meredith and a particular passion for Clara Middleton

(heroine of The Egoist). Everything that happened to Clara in The Lost Traveller is the sort of thing that happened to me, though many things are changed, many invented. I wanted The Lost Traveller to be a real novel – Frost in May was so much my own life. So I changed her name …’ In every other respect this novel begins where Frost in May ends. It is a vivid account of adolescence, of the mutual relationships of father, mother and daughter as Clara grows to

maturity and comes to grips with the adult world.

‘When I finished The Lost Traveller I thought of it as just being one book, and then suddenly I felt I wanted to write another one about my first marriage. That was The Sugar House, which I think is much the best of the three. In it I see Clara’s relationship with Archie (her husband) entirely through

the eyes of one person, as in Frost in May – I think that suited me much better.’

The Sugar House was published in 1952 and takes Clara through her first love affair, work as an actress and a doomed first marriage. Unsentimental,

often amusing, it is unusual for its moving description of a love between a man and a woman which is not sexual but which

is nevertheless immensely strong.

Beyond the Glass, which completed the quartet in 1954, is technically the most ambitious of the four novels, dramatically using images of

glass and mirrors to reflect Clara’s growing mental instability. For Antonia White describes her first encounter with ‘The

Beast’ in this novel, interweaving the story of Clara’s new love affair with a vivid description of her descent into and recovery

from madness. Antonia White remembers every moment of the ten months she spent in Bethlem Asylum (now the Imperial War Museum)

in 1922–3. It is the extraordinary clarity of her recollection of that madness which makes this novel so convincing.

Antonia White’s portrait of the life of a young Catholic girl in the first decades of this century is dominated by two themes

– the heroine’s intense relationship with her father, and the all-pervading influence of the Catholic faith. Antonia White’s

father centred everything on his only child, and Antonia was absolutely devoted to him. But to the end of his life he refused

to discuss one of her earliest traumas – the expulsion from the convent she recorded so faithfully in Frost in May – and she has obviously felt that she disappointed him bitterly by going her own way in life. As a Catholic, her relationship

with Catholic belief and practice has always been intense, a wrestling to live within its spiritual imperatives in a way which

accorded with her own nature, clinging to her faith, as she says, ‘by the skin of my teeth’. The struggle is brilliantly felt

in this quartet, permeating everything that happens to Clara, affecting her adolescence, sexuality, her relationships with

men.

To a modern reader these could be seen as experiences intimately connected with Clara’s slow progress towards madness, but

to Antonia White they were influences which were also profoundly enriching, in no way negative, part of an extraordinary life

which she recalls with a mixture of astonishment and laughter, and which she recreates with consummate skill in these four

novels.

When Antonia White completed Beyond the Glass her career as a novelist was over, but she always hoped to finish the story of Clara’s life. ‘I tried and tried because everybody

wrote to me and said you can’t leave Clara like this, and for years I tried, but only managed one chapter. Clara by this time

is married again – to Clive – and has given up her religion and is living the sort of life her father doesn’t approve of .

. . going out to work and having a wonderful time. Her father is very upset because Clara has given up her religion and he

feels she ought to have a child, because he wants a grandchild, but her mother doesn’t disapprove at all, she thinks Clara

has had such an awful time that it’s time she had some fun. Clara gets on much better with her mother now. I finally finished

what I still think is a very good chapter: Clara’s father has retired and they’re living in the Sussex cottage. Apart from

his trouble with his daughter, he is having the most lovely time of his life … they’ve extended the garden and he’s at

last got his great desire – a full-size croquet lawn where he spends all his time, playing out there in the blazing sun …’

Carmen Callil, Virago, London, 1979

Antonia White died on 10th April, 1980

Usually, Claude Batchelor was so eager to get down to Sussex for his annual three weeks holiday that, the moment the prizegiving

was over, he changed hurriedly into tweeds and was on his way within an hour. This year, for the first time, he had decided

to take things more easily and go down the following day. Perhaps because, at fifty, he was feeling the strain of having consistently

overworked since he came down from Cambridge, he was wearier than he could remember ever having been in his life.

On the morning of the day he and his wife were to travel down to Paget’s Fold he awoke with no joyful anticipation. On the

contrary, his mood was curiously oppressed. A nightmare, whose details were already fogged, had left him with a confused sense

of guilt and apprehension which he could not dispel. Normally, his dreams were rare, vivid and recountable. Of last night’s

he could remember nothing except that they had been of a kind he could have told no one and that they had concerned his daughter,

Clara.

He had reason enough to be anxious about Clara. She had been married only a few months and it was obvious that things were

not going well. Archie Hughes-Follett had begun to drink again and he suspected they were getting into debt. What troubled

him far more was the swift and violent change in Clara herself. The last time he had seen her, there had been a defiance,

even a coarseness in her looks and manner which had shocked him. Any real or fancied defect in his fiercely loved only child had always caused him

such pain that his first reaction was to be angry with her. He had been so angry with her that day that, though several weeks

had passed, he had felt none of his usual desire to placate her. He had deliberately tried to put her out of his mind and

had almost convinced himself that, if she chose to ruin her life, it was no concern of his.

His disturbing dream had made him sharply conscious of her again. As he dressed, he remembered that his son-in-law had rung

him up late the night before, asking if Clara was there. At the time, he had been not worried but annoyed. It was one more

black mark against Clara that her husband, drunk or sober, should not have found her at home when he returned. No doubt she

had gone to some horrible Bohemian party. He had always disapproved of their living in Chelsea, a quarter about which he had

lurid ideas. It was useless for his wife to assure him that it was Archie’s drinking which had made Clara hard, insolent and

slatternly. Since he was extremely fond of Archie and had been strongly in favour of the marriage, he preferred to think that

it was the deplorable effect of Chelsea on Clara that had driven his son-in-law back to the bars and drinking-clubs. Nevertheless,

as he came downstairs, he found himself feeling vaguely guilty that he had not mentioned that telephone-call to Isabel. He

would ring up after breakfast and make sure that Clara had come safely home.

In his anxious mood he had taken longer than usual to dress. His mother was waiting for him at the table where the bacon and

eggs were already congealing on their dish. As usual, she had refused to help herself to so much as a cup of tea before his

appearance. Breakfast was the one meal old Mrs Batchelor really enjoyed. At all others she was cowed by her daughter-in-law’s

exasperated glances. This morning she had looked forward to a deliciously prolonged chat with Claude who would be able, for

once, to eat without his eye on the clock. The prospect of his holiday would make him not only cheerful but extra attentive

to her as he always was before a parting.

To her dismay, Claude looked sombre and preoccupied. She tried several openings with no more response than a polite ‘Yes,

Mother’ or ‘Really?’ Finally, she risked mentioning her granddaughter. Even a rebuff would be better than indifference.

‘What a pity Clara won’t be going down to Paget’s Fold with you this year. You’ll miss her, won’t you? You were always so

happy together there. Summer after summer, ever since she was four years old.’

Claude said, none too amiably:

‘She wasn’t there last year either.’

‘Dear me … fancy my forgetting. My memory’s getting as bad as my hearing. Of course, last year she went off on that theatrical tour, didn’t she? I daresay she little realised that by the next summer she’d be a married

woman.’

‘Probably not.’ Claude’s eye wandered furtively towards The Times. Mrs Batchelor said in a suffering voice:

‘If you want to read the paper, don’t mind me, dear.’

‘No, no, of course not, Mother. I’m sorry.’

‘I thought you’d want to save it for the train. But if my chatting vexes you …’

‘Now, Mother, please. You know it doesn’t. I’m afraid I’m a little absent-minded this morning.’

‘You’re overtired,’ she purred. ‘I’m sure nobody at St Mark’s works as hard as you do. It must be bad for your health taking

all those private pupils as well as all your other teaching. I wonder Isabel doesn’t stop you.’

‘She couldn’t if she tried. How often have I told you I like work.’

‘You overdrive yourself, Claude. You can’t go on working day in, day out, even in the school holidays, and never taking a

proper rest.’

‘My dear, good Mother … I’m just about to take three whole weeks off.’

‘It’s not enough. What’s three weeks in a year? You’re not as young as you were, dear. I don’t like to say it, but you’ve

aged quite a lot in the last few months.’

‘Thank you!’

‘I only say it for your good, dear. I’m sure Clara would be upset if she saw how tired you look. She’s so devoted to her Daddy.’

‘Hmm.’ His mouth tightened.

‘Oh, but she is … It’s true she doesn’t come over and see us as often as she did when she was first married. I know I haven’t set eyes on her since she lunched here on her birthday.’

‘Neither have I.’

Mrs Batchelor’s dull onyx eyes brightened with curiosity.

‘Fancy! I made sure you had. Even though you hadn’t mentioned it. Though you usually tell me things even if Isabel doesn’t. And so often I don’t hear when she does. She speaks so fast and she gets impatient

if I ask her to repeat something. Yet I can always hear you quite plain, Claude. Well, you do surprise me! Not since her birthday! Why, that was in June.’

‘Yes.’

‘You don’t think she’s poorly? No, I’m sure Archie would have told you. Still I didn’t think her looking at all well that

day. In spite of her having got so much plumper since she married. Of course I think putting all that stuff on her face makes her look older. I’m sure anyone who didn’t know would have taken her for more

than twenty-two. It seems such a pity when you think of the lovely natural complexion she used to have.’

‘I entirely agree with you.’

‘I wonder you don’t say something to her.’

‘It’s no longer any business of mine. If Archie doesn’t object …’

‘I can’t see Archie objecting to anything Clara does. He’s so very devoted, isn’t he? By the way, I hope he’s better.’

Claude frowned and asked rather sharply:

‘Better? I hadn’t heard that he was ill.’

‘I was only thinking that he wasn’t well on Clara’s birthday and couldn’t come to lunch.’

Claude’s face relaxed.

‘Ah yes. I remember. Couldn’t have been anything serious.’

‘A bilious attack, I daresay. He doesn’t look as if he had a good digestion. He’s so painfully thin and his nose is always rather red. They say that’s a sign of chronic indigestion.’

‘Very unpleasant thing, dyspepsia.’

‘I wonder if Clara gives him proper food. She’s not had much experience of cooking, has she? I could have taught her for I’ve

had to cook all my life. Until I came to live with you and Isabel, that is. But I didn’t want to interfere. Still, it’s not

Clara’s fault that she’s always expected to have servants to do everything.’

‘I’m sure Archie’s extremely sorry that she hasn’t. In a year or two they’ll be able to afford as many servants as they like.’

‘When he comes into his father’s money? Dear me, they’ll be a very rich young couple then, won’t they? I must say Archie’s

wonderfully unspoilt when you think he was brought up in luxury. I know Isabel has never cared for him but I’ve got a very

soft spot for Archie. He’s so jolly and unaffected. And always so very pleasant to his old granny-in-law.’

‘I’m very fond of him myself.’

‘I know you are. Though he’s not clever like you. Anyhow Clara has enough brains for two, I always say. She looks rather discontented

sometimes. I suppose it’s because of all that bad luck Archie had about that Theatrical Club. I never did understand the rights

of it all.’

‘There were no rights. The whole thing was a disastrous, foolhardy speculation. I wish to goodness Archie had never got interested

in anything to do with the stage. However, I suppose now that he’s got this acting job, it’s better than nothing.’

‘I didn’t know he had a job. A part in a play?’

‘In some wretched musical comedy or other.’

Mrs Batchelor sniffed.

‘I do think you might have told me, Claude. You might have known I’d be interested.’

He said unguardedly:

‘I didn’t know myself till last night. Archie rang up.’

His mother exclaimed eagerly:

‘So it was Archie telephoning! Why, it was nearly midnight! I had my light on because I couldn’t get to sleep and was having a little read. I thought “Whoever could be ringing up so late

… how very inconsiderate!” Then I thought it must be one of those tiresome wrong numbers. Archie, well, fancy that! It must have given

you quite a shock, him ringing up at that hour. I expect you thought at first something must be wrong.’

He said stiffly:

‘He apologised for ringing up so late. He had been rehearsing.’

‘I suppose he was so excited about getting the job. Still, you’d think he could have waited till the morning.’

At that moment the telephone bell sounded from the study next door. Claude leapt to his feet.

‘Did you ever?’ said his mother. ‘Now whoever can it be this time? Surely not Archie again! Claude, there’s no need for you

to dash off like that. Why not let one of the servants answer?’

But Claude had already thrown down his napkin and hurried out of the dining-room. His unusual eagerness to answer the call

made Mrs Batchelor wonder whether he had been expecting it. All through breakfast he had seemed to have something on his mind.

Was something going on about which, as so often, she had not been told? Could there be some mysterious and interesting trouble

connected with Archie and Clara?

The minutes went by. Normally, Claude’s telephone conversations were brief. Old Mrs Batchelor’s devouring passion, curiosity,

had grown with her increasing deafness. More and more, the exciting scraps of gossip she longed to hear seemed to be deliberately

muttered in an inaudible whisper. The telephone was in the adjoining room. In his hurry to answer it, Claude might have forgotten

to shut the study door. On the pretext of looking for letters, she went out into the hall. To her annoyance, the study door

was closed. Pausing outside, she listened. Her son was the one person whose words she could usually make out even when he

did not raise his voice. All she could hear was an indistinct murmur, punctuated by long silences. Since he had only recently

acquired a telephone, Claude tended to shout into it. This morning he was evidently keeping his voice deliberately low. Mrs Batchelor’s curiosity began to itch like chilblains before the fire. She had to use

all her considerable will-power to move away from the door in the direction of the letter-box. She was only just in time.

Barely had she reached the hall table when the study-door flew open and Claude emerged. She said, without looking at him:

‘I just came out in case there were any letters. The postman’s often late at this time of year. I’m getting so deaf I don’t

always hear his knock.’

‘The post came ages ago. Mother, for goodness’ sake go and finish your breakfast.’ Claude’s voice was so irritable that she

wondered if he guessed she had been trying to eavesdrop. She peered up anxiously into his face. In the dim light, it looked

not accusing but distraught. She said timidly:

‘Something’s upset you, Claude? Not bad news, I hope?’

‘No, no. Just some trouble about a pupil. I’ll have to go out and deal with it at once.’

‘But, dear, you haven’t even finished breakfast …’

‘I’ve had all I want.’

He was already taking his bowler-hat from the peg on the hall-stand and picking up his chamois gloves. His mother was now

quite certain that he was lying. The itch of her curiosity became unbearable.

‘As urgent as all that? A pupil? Why, you’re supposed to be away on holiday.’

Claude did not answer. He was mechanically selecting a stick from the yellow drainpipe-like receptacle that stood just inside

the front door. ‘You’re not going out without going up to say goodbye to lsabel? I’ve never known you do that all the years

I’ve lived here!’

Claude was already opening the door. She went up to him quickly.

‘Not even time to give your old mother a kiss?’

He stooped and kissed her flaccid cheek.

‘I’ll go up and tell Isabel you had to go out,’ she said importantly. ‘Have you any idea when you’ll be back?’

‘Long before lunch, probably. There’s no need to tell Isabel.’

The door slammed behind him. His mother decided to ignore the last words. She could always pretend she was too deaf to hear

them or had misheard them as ‘Do tell Isabel’. Since her own curiosity had been so cruelly frustrated, there would be a certain

pleasure in arousing her daughter-in-law’s. True, Isabel was not particularly inquisitive but she would be annoyed that Claude

had gone out without saying goodbye. Old Mrs Batchelor wondered whether she dared risk implying that she knew more than she

did. Her mauve lips, with the mole on the upper one that so revolted her daughter-in-law, rehearsed soundlessly:

‘I’m sure Claude will tell you all in good time, dear. I know you wouldn’t wish me to break my promise.’

Shaking her large head on which the dark wig, curled in an Alexandra fringe, sat slightly askew, letting a few wisps of her

own white hair escape, she decided it was too dangerous. For a moment, she wondered if it was really worth climbing the six

flights to Isabel’s bedroom. She was heavily built and her short neck and tight stays made it necessary to pause and pant

a great deal when going upstairs. The she remembered a remark she had not been intended to hear but which had pierced her

capricious deafness.

‘If you really want to know, dearest, why I insist on going on having my breakfast in bed, it’s simply that I cannot face

the sight of your mother before lunch.’

The mauve lips tightened. Picking up her long, heavy black skirts with one hand and clutching the banisters with the other,

old Mrs Batchelor planted her velvet-slippered foot firmly on the first stair.

When Claude returned home some three hours later, his wife came quickly down the stairs as he opened the front door.

‘I’ve been listening for your key. Wherever have you been all this time? I was getting anxious.’

‘I’ll tell you in a moment,’ he said hurried. ‘Come into the study, Isabel. I must talk to you.’

It had been too dim in the hall for her to see his face. When the light from the study window revealed it, she exclaimed:

‘Dearest, whatever’s the matter? You look ghastly. Are you ill?’

‘No … no.’ He shook his head impatiently. ‘We’d better sit down. This is going to take some time.’

He settled her in the big faded green armchair that had been in his rooms at Cambridge and, from force of habit, seated himself

at his desk. Taking one of the fountain pens from the bowl of shot in which he always stuck them, he began to screw and unscrew

its cap, frowning as he did so. Well as Isabel knew his expressions, she could not decipher that frown. Did it mean anger

or pain? He was silent for so long that she began to examine her conscience. If it were anger, it must be over something much

graver than her latest filching from the housekeeping money. Only once or twice in their married life had she seen his face

drained of its usual fresh colour to that ashy yellow. In the hard light of the window by the desk his few lines showed up as if they had been pencilled in. She began to be frightened. There was only one secret of hers whose discovery

could possibly have made him look like that.

Unable to bear the suspense, she probed him gently:

‘Your mother came up all those stairs to tell me you’d rushed out. She said something about an urgent ’phone call from a pupil.

But her manner was so odd, I wondered if …’

‘I told her a lie,’ he interrupted. ‘It was Clara who rang up. I’ve been over in Chelsea all this time.’

‘Clara!’ Isabel was so relieved that she forgot to be surprised. Confidently, she raised her head and looked straight at him.

He too had been avoiding her eyes but now he met them. The misery in his made her gasp:

‘She’s ill? … She’s had an accident?’

‘No, no. Not exactly ill.’ ‘Is it that wretched Archie ? Has he done something dreadful?’

He said sharply:

‘You’re always ready to think the worst of Archie, aren’t you? In this case you’re wrong.’

‘You don’t mean it’s Clara who’s done something?’

‘She proposes to do something that distresses me more than I can say.’

Isabel’s frightened face relaxed. She was almost smiling as she said:

‘She’s going to leave him? I’m not surprised. I only wonder she’s stood it as long as she has.’

Claude’s blue eyes, which had gone so dull, snapped with some of their old brightness.

‘Really, . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...