‘… seven, eight, nine …’ Martha Rodwell is counting under her breath. On ten she opens her eyes and her left hand – freckled, slim and workmanlike – slackens its grip on the arm of the airline chair. Little by little the slope of the gangway begins to level and the grinding whine of the engines slows to a growl.

‘Well,’ she murmurs, ‘I guess we can all breathe again now!’ The man in the seat but one from her own lifts his head from the well of a ring binder, spearing her with light blue eyes.

‘I’m sorry?’ he says. ‘What did you say?’

‘Oh!’ – Martha laughs awkwardly – ‘I… Well, I just… Oh, it was nothing...’

Her attention is caught by the seatbelt sign. Large, illuminated letters remind her even now the plane is climbing, climbing… She rubs a sticky palm on the denim of her skirt.

The cabin is crowded but not quite full: families with squirming children, a handful of middle-aged executives, three nuns in teal-blue habits and a few solitary travellers like herself.

‘Do you know’ – the words are out of her mouth before she can stop them – ‘that eighty per cent of aviation accidents occur in the first ten seconds immediately after takeoff or during the last ten seconds before landing?’

Her neighbour blinks in surprise. ‘If you say so.’ His accent brings to mind those imported period dramas she watches at the weekend, a microwave dinner on her lap and a glass of Rita Hills red at her elbow.

He picks up his binder. He has another on his lap and has placed a stack of loose papers on the empty seat between them. They were all tied together with a pink ribbon that he pulled off as soon as Martha sat down and is now draped over his knee. In a moment it’s going to fall off and work its way under the chair in front of him and he will lose it altogether. Martha thinks about mentioning this but he is already engrossed in his reading again, swiping the occasional sentence with a highlighter pen and daubing the page with yellow Post-it notes from a pad of them tucked into the palm of his other hand. His concentration is fixed and fierce and Martha sees how young he is. Not a great deal older than her own daughter, in fact.

The thought of Janey pokes her in the ribs as sharply as a pointed stick. Recently, Martha hasn’t been able to shake the sense that something is wrong. Almost as soon as Janey left for England the previous fall her correspondence dwindled to minimal, dry fragments of text, the very absence of words a restatement of all the hurtful sentiments she’d yelled at Martha before she left. Now she telephones more often, but Martha has to perform a monologue just to keep the call afloat, or else ask a stream of questions that sound even to her own ears like an inquisition and are answered with merely a dead-end ‘yeah’ or ‘fine’. It feels like struggling to lift a heavy weight while Janey watches from afar refusing to lift so much as a finger to help.

The cabin fills with the snap of metal clips, the papery rustle of clothes and the rattle of trolleys. A few moments later a young female member of the cabin crew offers her something to drink. ‘Champagne, perhaps?’

‘Yes,’ Martha says, she would like a glass of champagne. She deserves it, after the recent, horrible weeks.

The plane is horizontal now, the hum of the engines steady and relaxed. Tentatively, she leans back in her seat and looks out of the window. The sky is a blinding, brutal blue and the carpet of rolled-up cloud so resembles snowdrifts that she idly assumes they are skimming the ice-fields of Canada and Greenland until an inner voice reminds her that the actual ground curves somewhere out of sight, far, far below. She averts her gaze and takes several quick sips of too-sweet, imitation fizz.

‘Fuck!’

Martha’s neighbour is brandishing a half-opened bottle of tonic water and regarding it with alarm. A stream of bubbles has burst out of the seal and is cascading onto his papers. His other hand is burrowing into the recess of a trouser pocket searching, she assumes, for a handkerchief, but the precarious organisation of his papers appears vulnerable to the smallest sideways movement.

Martha rummages in her travel bag – a small practical rucksack, the many pockets of which she has packed for just such contingencies – and presents him with a packet of paper tissues. For a minute or two he carefully dabs the page of inky blotches and then searches for somewhere to put the sodden tissues.

‘Let me,’ Martha says, and stuffs them into her glass, which is now conveniently empty.

‘Hey. Thanks.’ He has the lanky kind of build that belongs on a running track or a soccer pitch rather than a baseball field. It isn’t so apparent sitting down but now she can see how he is twisted sideways by the cramped seating and how his back hunches awkwardly over the inadequate fold-down table. Despite the formality of a suit there’s still the air of the college student about him. His shirt has loosened from his waistband, the knot of his tie has twisted under his collar and his fairish hair is floppy at the front in a boy-band sort of way. His eyes flick over her face and then he picks up his pen again. ‘Ex parte injunction in the QBD as soon as I get back. Sorry to be unfriendly.’

Martha says, ‘Of course.’ She has no idea what he’s talking about.

An hour or so has passed. Martha’s novel is open, face down over her knee. With rapturous horror she’s watching the outside light deepen to velvet indigo as they hurtle towards the enveloping night. Before long she hears clinks and chinks and snatches of conversation from the galley and the hot smell of food begins to waft through the cabin. The drinks trolley clatters around and when Martha asks for a French red (she’s en route to Europe, after all) the young hostess hands her two miniature bottles of Merlot. Shortly after that comes a tray piled with an assortment of foil cartons and cellophane packages. Once or twice she casts a glance at her neighbour but he continues to read as he forks chunks of chicken into his mouth, the binder jammed uncomfortably between his lap and the table.

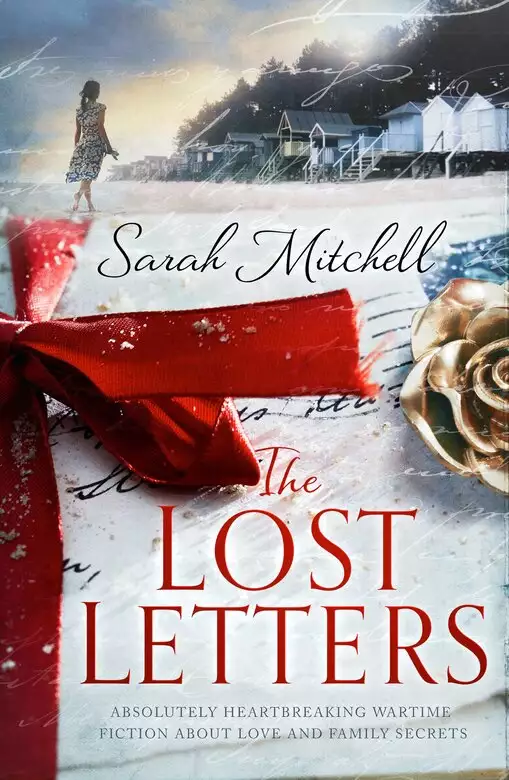

Soon Martha can barely feel the forward motion of the plane. Since her father died just under a month ago she’s felt a crushing physical fatigue, as if she has to drag her grief around like ankle chains. He was found on the porch, surrounded by sheets of writing paper skimming over the lawn and skewered to the rose bushes. Six months previously he had stepped down from the municipal council to write his memoirs. Elizabeth, her sister, had offered to proofread them but she told Martha that he refused point-blank to let her see them.

‘Not until they’re finished,’ he said. And then he mentioned, casually, as if it were of no import at all, that in order to finish them he would need to go back to England.

‘Why,’ Elizabeth asked Martha on the telephone that evening, ‘does he want to go back now, when he hasn’t set foot on British soil for seventy years?’ Martha didn’t know. But when he died they discovered he had booked a hotel and rented a beach hut in a small English coastal town, called Wells-next-the-Sea, for the whole of May.

Martha thinks she ought to be dealing with the bereavement better; she’s a forty-four year-old schoolteacher, for heaven’s sake – she has said this to herself, scrabbling for a tissue at the lights or hijacked by tears at the checkout packing groceries into a box – but she feels older, exposed. As if mortality is tapping at the window. A week ago she dreamed of him. He was crouched with a group of boys in the bottom of a wooden boat that was pitching and tossing in a grey, biblical sea. While Martha watched, a thin mist of music rose from the water as the children began to sing, oblivious to the foam-tipped waves that slopped over their shoes. She woke feeling wretched and confused. Her father had never once wanted to talk about his evacuation, so why was she dreaming of it now?

She and Elizabeth spent the week after the funeral clearing out his house. On the first morning Elizabeth found the printout of their father’s memoirs in his study and spent the afternoon meticulously putting in order all the papers that had been scattered so carelessly around his porch. Over tacos for dinner, both of them too drained for anything but comfort food, her brow furrowed as she spoke to Martha about it. ‘The strange thing is,’ Elizabeth said, ‘the story only starts when Dad turned twenty and he met Mum at the benefit dance.’ (Over the years they had both been told the story countless times of how their mother’s date had gotten too drunk to walk her home and their father had stepped up to the moment and into his future.) ‘There’s no mention of anything before then at all.’

‘Maybe there’s some stuff on his computer he hadn’t printed out?’

Elizabeth shook her head, taco dangling from one hand. ‘The version on the computer is no different from the one in the study. I already checked.’ Late into the following night, sustained by a combination of Haagen Dazs, tea and Amaretto, Martha read the printout herself. She found that her sister was right; the first twenty years of their father’s life were missing entirely.

The empty trays have acquired a sluttish appearance, overflowing with discarded packaging, half-eaten food, and empty bottles. Martha frees her flight blanket from its cellophane sleeve, tucks it over her legs and all the way to her chin. Presently, the lights dim and a fragile hush descends on the cabin, broken only by the distant wail of a baby. Perhaps there’s nothing to flying after all. The sky, she sees, is now a fathomless black. Martha stares at it for a second, and then snaps down the shutter.

She must have fallen asleep because her body reacts even before she is conscious of processing the words. She feels winded, the air knocked from her lungs, her stomach gripped by a sick and panicked cramp. She opens her eyes. The cabin is bright as day, both the overhead and window lights blazing at full intensity. A recorded voice, loud and compelling, floods the tannoy system.

‘EMERGENCY. EMERGENCY. PUT THE MASK OVER YOUR NOSE AND MOUTH AND BREATHE NORMALLY. EMERGENCY. EMERGENCY…’

Martha gasps, ‘Oh… Oh!’ This is it, she thinks. This is it. Any second, any instant, the plane will fall away beneath them. A vision of the stricken aircraft tumbling and turning through layer upon layer of cloud appears before her eyes. Or instead a gaping crack will open and she will be sucked from her seat, shrieking and grabbing at nothing, into the freezing, unbreathable air. Will I die, she wonders wildly, before or after I hit the sea? And then she notices the pink ribbon curled on the floor. And then a thought hits her as if a brick has fallen into her lap.

Janey.

Janey doesn’t know where she is. Janey will hear of the plane crash on the radio while she’s eating breakfast. Her spoon will hover, dripping milk, and she’ll pull the sad, respectful face that people make when they learn of a tragedy that doesn’t concern them. Later in the day Elizabeth will call her.

‘What do you mean?’ Janey will say, not understanding at first, winding a clump of butter-coloured hair around her index finger in that last blissful moment before her life switches course. ‘What do you mean my mother was on the plane? She can’t have been. Why would she be coming to England?’

‘EMERGENCY. EMERGENCY. PUT THE MASK OVER YOUR NOSE AND MOUTH AND BREATHE NORMALLY…’

‘Oh!’ Martha says again. There’s something dangling in front of her face on a long string. The cabin is full of yellow plastic masks and wide, frightened eyes shining over the top of them. It’s eerily calm, nobody is screaming or shouting, even the baby has stopped crying, although one of the nuns is crossing herself and chanting under her breath.

Martha reaches for her mask but her arms feel numb and heavy. Finally her fingers close around the elastic and she tugs the yellow cone towards her and puts it over her face. She glances across the seats next to her. The guy with the ring binders is jerking his cord, but the mask is stuck about six inches from his face and his blue eyes are manically ablaze. Tremulously, Martha lifts her own mask away so that she can see better what’s happened. Her mind is racing. Any second, the cabin oxygen will run out and she’ll suffocate. Any second, the plane will fall from the sky or burst into a million pieces. She’s about to die and now she’s not wearing the one thing that might possibly save her. The young man is yanking hopelessly at his useless contraption as Martha unclips her seatbelt and staggers upright.

‘Let go,’ she says. ‘It’s knotted.’ He drops his hand, and Martha twists and threads the string back on itself until it releases. She places the cup over his nose and mouth, adjusts the strap around his stubbled neck, and sinks into her seat again.

Her relief is short-lived. There’s no oxygen coming through her mask, none at all. Perhaps she’s doing it wrong? She should never have taken it off. She sucks hard at the inside of the plastic but it’s dry and airless and smells of rubbery chemicals and a sickly trace of her own perfume. She jabs at the cord but it makes no difference. Her neighbour seems to be in a similar position because he lifts up his own yellow cup and takes a breath from the cabin before settling it back over his face again. Martha does the same thing. It strikes her that the plane is still horizontal. The emergency announcement has stopped and the unruffled drone of the engines fills her ears. She sees that some of the passengers have taken their masks off altogether and are looking along the gangway to where the young flight attendant has got out of her seat and is making her way to the cockpit.

A moment later there’s a buzzing on the tannoy system followed by the pilot’s voice. Martha listens to a rich blur of words she ought to understand but they are somehow indistinct and incomprehensible. Several times she hears ‘mistake’ and ‘unfortunate’ and ‘apology’, but her brain seems unable to construct a sensible sentence from them. What kind of mistake is he talking about? She remembers vanished aircrafts plunging into oceans thousands of miles off-course. Is it that kind of mistake?

The young man grabs her arm. ‘What did he say? What’s gone wrong?’

Martha shakes her head in confusion.

A few rows ahead of them an older flight attendant is trying to push some of the masks back into their compartments but they continue to bob and dangle about people’s heads like a swarm of yellow jellyfish. The tension in the cabin appears to be dissipating. A woman in the row ahead has even picked up her book again. A minute later the older hostess bustles by their seats. The young man catches her elbow. ‘What the hell was that all about?’

The air hostess stops. Her face is white but smudged with sharp spots of embarrassed pink. She leans across them as she speaks, lowering her voice. ‘A gentleman in first class was taken ill. He needed to use an oxygen mask and the captain activated the whole emergency system by mistake. He turned it off again but now we can’t get the masks to go back up.’

‘Is that all it was?’ Martha asks weakly. ‘There’s nothing wrong with the plane?’ She frees her arm from her neighbour’s clutch but a part of her is still braced, waiting for a sudden, disintegrating lurch.

The air hostess grimaces. ‘Gave us all a bit of fright, didn’t it?’

‘Fright?’ repeats Martha’s neighbour as though that hardly covered it. He looks at Martha and then at the flight attendant. ‘Well we both need a fucking drink!’

He runs his fingers through his front lock of hair and then holds his hand out to Martha. ‘Raymond – Ras. Ras Alby.’ He pauses. ‘Thank Christ we didn’t need those masks.’

‘Martha,’ Martha says. ‘Martha Rodwell.’ A second later. ‘Did you think we were going to crash?’

‘Yup, part of the twenty per cent. So much for your fucking statistics.’ His voice is saltier now, as if the stress has stripped away some of its polish. When the air hostess returns with four small bottles and two plastic tumblers he pours a brandy and gives it to Martha with a trembling hand.

‘Twenty per cent…? Oh!’ – Martha laughs – ‘I see what you mean.’ She takes several gulps in quick succession, pauses and then has another one. The kick of it burns a path through her stomach and ignites a wild and growing euphoria. She isn’t about to die! Ras smiles at her. Definitely a boy-band smile. He’s very attractive, she sees. And far, far too young, she sternly reminds herself.

‘So, Martha,’ Ras says, emptying two bottles at once into his own tumbler, ‘what takes you to London?’

‘My daughter for one thing.’ Martha looks down into the amber pool of alcohol. ‘My daughter, Janey. She’s studying in England. At Cambridge University.’ She can’t stop a note of pride from creeping into her voice.

‘Nice!’ Ras says approvingly, and tips a long draught of brandy down his throat. ‘She’ll be pleased to see you then.’

‘Well,’ Martha says. Her voice dips. ‘I hope so.’ She opens her mouth, and then shuts it again while she finds the best way of putting it; how does she describe the weekly battles and the slammed doors, the sheer energy her daughter expends keeping her mother as far out of her life as possible? ‘As it happens Janey’s going through an independent phase right now.’

‘An independent phase.’ Ras swills the sentence around his mouth. He looks amused at something. ‘Right. So where will you stay?’

‘Well, I shall see Janey, of course, but I plan to stay in Norfolk. My hotel is booked for the next four weeks.’

‘Norfolk?’ Ras’ eyebrows shoot upwards.

Martha starts to say that her father hired a beach hut for the whole of May, only he died, he died a month ago, and now she is going to use it herself, but her voice tails away before she can describe the situation properly. She sees her father shuffling around his redundant study, tidying his few remaining council papers, straightening picture frames, breathing hard on a photograph and then rubbing the glass with the sleeve of that raggedy blue coat he still wore as a kind of bathrobe, the one with his name, Lewis Rodwell, sewn into the collar with cotton tape. She hears his voice, confident and crusty, dismissing concerns for his health with the same impatience he showed to any insinuation of frailty – to most things in fact. She feels a pull in her chest, like a thread tugging loose, there’s a hot, pinching sensation across the bridge of her nose and her eyes begin to pool.

Ras shifts uncomfortably and transfers his gaze from her face to the seat back in front of him. Martha pulls a tissue from her sleeve and blows her nose. Eventually, she asks with a forced, brittle breeziness, ‘Do you know Norfolk, Ras?’

‘Nope. Live in London. Born and raised in the Cornish metropolis of Shag Rock.’ He looks at her sideways, twisting his lips in delight.

Martha splutters a mouthful of drink. ‘Shag Rock! Is that actually a place?’

‘Yeah, it actually is. Well, it’s a part of a place called Downderry, but Downderry doesn’t sound like nearly so much of a good time.’

Martha laughs and Ras sits back in his chair again with an expression of relief. He pauses and then cocks his head. ‘So! The whole of May on an English beach? That’s pretty bold.’

‘Bold in a good way?’

Ras shrugs. ‘Well, I guess that depends on Norfolk. A Spanish beach would make more sense to me. Or France. Anywhere else in Europe, really. Since you’ve come all this way.’

‘Elizabeth thinks it’s crazy too.’

‘Elizabeth?’

‘My sister.’

‘Ah.’

Ras is looking down at his binder. Martha suspects he’s lost interest. She closes her eyes and Elizabeth comes to mind, as she always does – click, click – heels first. They trip briskly from one engagement to the next, drawing attention to the apple of her calves, the bustle of her hips. The whole time she talks she never keeps still. Even when Elizabeth telephones she’s either in transit or switched to speakerphone so she can combine the conversation with another, more productive activity. Everything she does, even the way she speaks, is a lesson in efficiency. ‘Well!’ she might say, or ‘Fine!’ A whole army of other words will be jostling behind the front man but she never has to utter one of them to make their meaning felt.

‘Right!’ was all Elizabeth said when Martha announced that she had negotiated four weeks’ leave and was going to England. Martha was about to explain that she badly needed to see the Norfolk coast for herself and discover why their father had chosen such an odd location to finish his book, but Elizabeth snapped shut her purse, pecked Martha on the cheek and left for her Pilates’ class. Martha knows Elizabeth’s lack of enthusiasm about the trip is due, at least in part, to the number of their father’s possessions still to be disposed of; some of the more personal ones they haven’t yet been able to bring themselves to give or throw away, others, such as his computer, require – according to Elizabeth – hours of painstaking attention. ‘You can’t just trash a computer, Martha! It has to be cleaned up first.’ In their rush to clear the house the items have been stacked in Elizabeth’s spare room.

It is highly likely Elizabeth also suspects that Martha’s other, unstated, reason for taking such a lengthy vacation is to spend time with Janey. Martha is reluctant to admit the strength of that desire even to herself, let alone Elizabeth; the last time Martha confided to Elizabeth the problems she’d been having with Janey, Elizabeth’s only, rather hurtful, response was to say, ‘It’s been the two of you for so long, Martha. It’s not surprising you’re having such a hard job letting go.’

The silence swells and Ras picks up the binder with an apologetic shake of his head.

Martha is disorientated. She seems to have been sitting here forever, the whole world shrunk into the capsule of the plane. They could be anywhere. They could be travelling at hundreds of miles an hour or going nowhere at all, without a fixed point to measure against it’s impossible to tell. And what time is it? Presumably there’s a proper answer to that question, depending on their longitude and speed – really, she ought to know – but the query feels man-made, like the shiniest of polyesters. She swallows the last of her brandy, leans her head against the chair-wing and lifts the edge of the window flap.

‘Oh, Ras look!’

It seems they’ve flown right through the night and out the other side. The golden disc of the sun is clipping the horizon. The eastern sky is a dazzling lapis blue and brushstrokes of pink and tangerine paint the blanket of clouds below. ‘Oh do look!’ Martha says again and pushes the flap completely open so that Ras, when he lifts his head from the page, can see it too.

When she wakes, an ordinary light fills the cabin. There’s the smell of coffee and the young flight attendant is handing out more plastic trays. Martha’s head is throbbing slightly and her mouth is dry. She drinks a small tub of juice without pausing for breath and asks for water. The mood is businesslike and expectant. Breakfast is whipped away before she has even finished eating and she takes the chance to lever herself into the gangway and join the queues to the restrooms.

The light inside the cubicle shines cold and unforgiving. Traces of grey fleck her curls where the auburn has begun to drain over the past few years and papery fork marks imprint the fine skin around her eyes. She finds tinted moisturiser, mascara and a peachy lipstick, brushes the life back into her hair and hoiks up her skirt so she can pull her shirt down more snugly over her bust. Finally, she fishes further into her make-up bag and takes out a pair of earrings. As she threads the silver hooks through her earlobes, small squares of translucent blue glint back at her in the mirror. Something about their colour and simplicity is reminiscent of her truncated youth, that brief period before she rated careers based upon their daycare and health insurance.

By the time she returns passengers are gathering belongings, checking their watches and filling in landing cards. Only the yellow field of nodding masks lets slip that the flight has been different from any other. As she squeezes past Ras his eyes seem to graze her face and then slide downwards to her chest, but she’s too surprised to register the moment and a second later he’s reverted to his papers.

The plane tilts downward and Martha’s ears begin to hurt. A fog of a rubbed-out white swirls forever beyond the window and then all at once they break into an earthy palette of greens and browns, the colours of solid things, of fields and roads and Monopoly houses sprawled beneath the weak English sun. The young flight attendant arrives looking agitated and gestures that Ras must pack up his papers and fold his table away. He says something to Martha but she can’t hear a thing.

‘My ears are blocked,’ she says, shaking her head. Her voice sounds hollow and far away.

All at once the wing below her disappears and the plane banks. The airport is underneath them now, the spidery outline of gates and terminals, the tarmac grids and orderly rows of shiny planes. As the world straightens again, a river of grey rises to meet them. Martha has a sudden sensation of tremendous speed, there is a jarring thump and then the engines scream manically backwards until the plane abruptly capitulates and they are pottering down the runway as if out for a Sunday drive. It is only once the captain has welcomed everyone to London and informed them the weather is damp with scattered cloud – which she can see for herself anyway – it occurs to Martha that she forgot to count to ten as they landed.

With a wave of his hand Ras jumps into the gangway and then there’s a surge of families hell-bent on getting out as quickly as possible before Martha can gather her coat, her bags and edge into line. She steps out of the tunnel and into the terminal. English soil! But there’s nothing remarkable about it: an endless walk through corridors echoing with footsteps and the rumble of suitcase wheels, a ride on a conveyor belt between a plethora of billboards advertising banks, and the light, constant patter of rain on the windows.

In the immigration hall she makes her way towards the desks amongst a mass of sleep-deprived faces. While she’s waiting in line she switches on her phone. It bleeps and blusters as it scrabbles to get its bearings. A little girl with brown-button eyes watches her over the top of a shoulder draped in gold cloth. Martha holds up the screensaver to show a cute Dalmatian puppy (taken at the ‘bring your pet to school’ day) but the little girl looks away and her mother edges a few steps further forwards, although the queue hasn’t actually moved. Martha puts the phone in her jacket pocket. How she would like to call Janey – for Janey to be expecting that call.

‘I’ve arrived!’ she would say. ‘But you’ll never guess what happened on the flight!’

Martha sighs. It feels impossible to call Janey.

By the time her passport has been checked, she’s hauled her enormous suitcase from the baggage reclaim and wheeled it under the noses of two vicious-looking Alsatians her spirits are sinking further.

In the arrivals hall there are hugs and tears and home-made placards everywhere she looks. One banner reads, Welcome home Auntie Linda , another, Great job Twickenham ladies! Small arms encircle adult necks, elderly spouses are holding hands like teenagers, and one young couple is brazenly entwined in the middle of the walkway so that Martha has to manoeuvre her suitcase around them. It should be heart-warming but instead she feels her heart is breaking. The people she loves aren’t here. And there seem so few of them anyway; the crucial members of her little family – Janey, Elizabeth, her father – are dreadfully depleted. Who would come to meet her at an airport now?

She stops and the crowds swarm past like water round a stone. She has to find a route to central London. It occurs to her that she should have arranged for a cab. If she saw a scrap of paper with Martha Rodwell written in wonky capitals she would at least feel awaited – not entirely alone, not completely invisible. She eases the rucksack from her shoulders and balances it on top of he. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved