- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

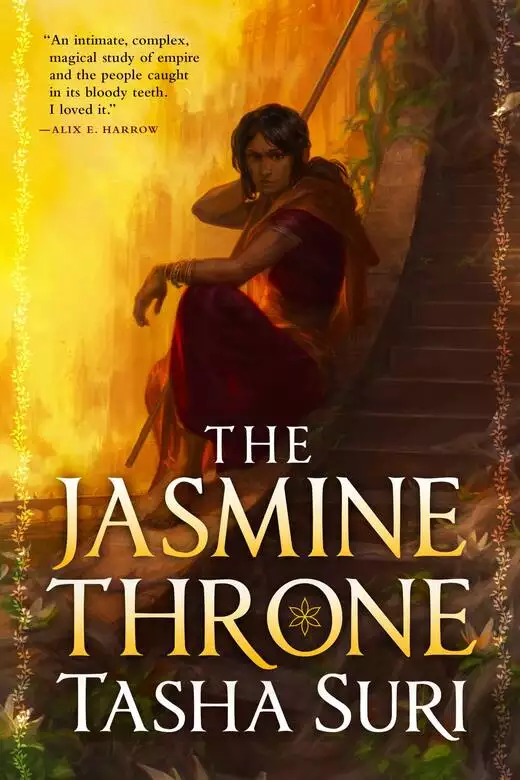

"RAISES THE BAR FOR WHAT EPIC FANTASY SHOULD BE." —Chloe Gong, author of These Violent Delights

A ruthless princess and a powerful priestess come together to rewrite the fate of an empire in this “fiercely and unapologetically feminist tale of endurance and revolution set against a gorgeous, unique magical world” (S. A. Chakraborty).

Exiled by her despotic brother, princess Malini spends her days dreaming of vengeance while imprisoned in the Hirana: an ancient cliffside temple that was once the revered source of the magical deathless waters but is now little more than a decaying ruin.

The secrets of the Hirana call to Priya. But in order to keep the truth of her past safely hidden, she works as a servant in the loathed regent’s household, biting her tongue and cleaning Malini’s chambers.

But when Malini witnesses Priya’s true nature, their destinies become irrevocably tangled. One is a ruthless princess seeking to steal a throne. The other a powerful priestess desperate to save her family. Together, they will set an empire ablaze.

"An intimate, complex, magical study of empire and the people caught in its bloody teeth. I loved it.” —Alix E. Harrow, author of The Ten Thousand Doors of January

"Gripping and harrowing from the very start." —R. F. Kuang, author of The Poppy War

"Suri’s incandescent feminist masterpiece hits like a steel fist inside a velvet glove. Simply magnificent." —Shelley Parker-Chan, author of She Who Became the Sun

"A fierce, heart-wrenching exploration of the value and danger of love in a world of politics and power." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"This cutthroat and sapphic novel will grip you until the very end." —Vulture (Best of the Year)

"Lush and stunning....Inspired by Indian epics, this sapphic fantasy will rip your heart out." —BuzzFeed News

A ruthless princess and a powerful priestess come together to rewrite the fate of an empire in this “fiercely and unapologetically feminist tale of endurance and revolution set against a gorgeous, unique magical world” (S. A. Chakraborty).

Exiled by her despotic brother, princess Malini spends her days dreaming of vengeance while imprisoned in the Hirana: an ancient cliffside temple that was once the revered source of the magical deathless waters but is now little more than a decaying ruin.

The secrets of the Hirana call to Priya. But in order to keep the truth of her past safely hidden, she works as a servant in the loathed regent’s household, biting her tongue and cleaning Malini’s chambers.

But when Malini witnesses Priya’s true nature, their destinies become irrevocably tangled. One is a ruthless princess seeking to steal a throne. The other a powerful priestess desperate to save her family. Together, they will set an empire ablaze.

"An intimate, complex, magical study of empire and the people caught in its bloody teeth. I loved it.” —Alix E. Harrow, author of The Ten Thousand Doors of January

"Gripping and harrowing from the very start." —R. F. Kuang, author of The Poppy War

"Suri’s incandescent feminist masterpiece hits like a steel fist inside a velvet glove. Simply magnificent." —Shelley Parker-Chan, author of She Who Became the Sun

"A fierce, heart-wrenching exploration of the value and danger of love in a world of politics and power." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"This cutthroat and sapphic novel will grip you until the very end." —Vulture (Best of the Year)

"Lush and stunning....Inspired by Indian epics, this sapphic fantasy will rip your heart out." —BuzzFeed News

Release date: June 8, 2021

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Jasmine Throne

Tasha Suri

In the court of the imperial mahal, the pyre was being built.

The fragrance of the gardens drifted in through the high windows—sweet roses, and even sweeter imperial needle-flower, pale and fragile, growing in such thick profusion that it poured in through the lattice, its white petals unfurled against the sandstone walls. The priests flung petals on the pyre, murmuring prayers as the servants carried in wood and arranged it carefully, applying camphor and ghee, scattering drops of perfumed oil.

On his throne, Emperor Chandra murmured along with his priests. In his hands, he held a string of prayer stones, each an acorn seeded with the name of a mother of flame: Divyanshi, Ahamara, Nanvishi, Suhana, Meenakshi. As he recited, his courtiers—the kings of Parijatdvipa’s city-states, their princely sons, their bravest warriors—recited along with him. Only the king of Alor and his brood of nameless sons were notably, pointedly, silent.

Emperor Chandra’s sister was brought into the court.

Her ladies-in-waiting stood on either side of her. To her left, a nameless princess of Alor, commonly referred to only as Alori; to her right, a high-blooded lady, Narina, daughter of a notable mathematician from Srugna and a highborn Parijati mother. The ladies-in-waiting wore red, bloody and bridal. In their hair, they wore crowns of kindling, bound with thread to mimic stars. As they entered the room, the watching men bowed, pressing their faces to the floor, their palms flat on the marble. The women had been dressed with reverence, marked with blessed water, prayed over for a day and a night until dawn had touched the sky. They were as holy as women could be.

Chandra did not bow his head. He watched his sister.

She wore no crown. Her hair was loose—tangled, trailing across her shoulders. He had sent maids to prepare her, but she had denied them all, gnashing her teeth and weeping. He had sent her a sari of crimson, embroidered in the finest Dwarali gold, scented with needle-flower and perfume. She had refused it, choosing instead to wear palest mourning white. He had ordered the cooks to lace her food with opium, but she had refused to eat. She had not been blessed. She stood in the court, her head unadorned and her hair wild, like a living curse.

His sister was a fool and a petulant child. They would not be here, he reminded himself, if she had not proven herself thoroughly unwomanly. If she had not tried to ruin it all.

The head priest kissed the nameless princess upon the forehead. He did the same to Lady Narina. When he reached for Chandra’s sister, she flinched, turning her cheek.

The priest stepped back. His gaze—and his voice—was tranquil.

“You may rise,” he said. “Rise, and become mothers of flame.”

His sister took her ladies’ hands. She clasped them tight. They stood, the three of them, for a long moment, simply holding one another. Then his sister released them.

The ladies walked to the pyre and rose to its zenith. They kneeled.

His sister remained where she was. She stood with her head raised. A breeze blew needle-flower into her hair—white upon deepest black.

“Princess Malini,” said the head priest. “You may rise.”

She shook her head wordlessly.

Rise, Chandra thought. I have been more merciful than you deserve, and we both know it.

Rise, sister.

“It is your choice,” the priest said. “We will not compel you. Will you forsake immortality, or will you rise?”

The offer was a straightforward one. But she did not move. She shook her head once more. She was weeping, silently, her face otherwise devoid of feeling.

The priest nodded.

“Then we begin,” he said.

Chandra stood. The prayer stones clinked as he released them.

Of course it had come to this.

He stepped down from his throne. He crossed the court, before a sea of bowing men. He took his sister by the shoulders, ever so gentle.

“Do not be afraid,” he told her. “You are proving your purity. You are saving your name. Your honor. Now. Rise.”

One of the priests had lit a torch. The scent of burning and camphor filled the court. The priests began to sing, a low song that filled the air, swelled within it. They would not wait for his sister.

But there was still time. The pyre had not yet been lit.

As his sister shook her head once more, he grasped her by the skull, raising her face up.

He did not hold her tight. He did not harm her. He was not a monster.

“Remember,” he said, voice low, nearly drowned out by the sonorous song, “that you have brought this upon yourself. Remember that you have betrayed your family and denied your name. If you do not rise… sister, remember that you have chosen to ruin yourself, and I have done all in my power to help you. Remember that.”

The priest touched his torch to the pyre. The wood, slowly, began to burn.

Firelight reflected in her eyes. She looked at him with a face like a mirror: blank of feeling, reflecting nothing back at him but their shared dark eyes and serious brows. Their shared blood and shared bone.

“My brother,” she said. “I will not forget.”

Someone important must have been killed in the night.

Priya was sure of it the minute she heard the thud of hooves on the road behind her. She stepped to the roadside as a group of guards clad in Parijati white and gold raced past her on their horses, their sabers clinking against their embossed belts. She drew her pallu over her face—partly because they would expect such a gesture of respect from a common woman, and partly to avoid the risk that one of them would recognize her—and watched them through the gap between her fingers and the cloth.

When they were out of sight, she didn’t run. But she did start walking very, very fast. The sky was already transforming from milky gray to the pearly blue of dawn, and she still had a long way to go.

The Old Bazaar was on the outskirts of the city. It was far enough from the regent’s mahal that Priya had a vague hope it wouldn’t have been shut yet. And today, she was lucky. As she arrived, breathless, sweat dampening the back of her blouse, she could see that the streets were still seething with people: parents tugging along small children; traders carrying large sacks of flour or rice on their heads; gaunt beggars, skirting the edges of the market with their alms bowls in hand; and women like Priya, plain ordinary women in even plainer saris, stubbornly shoving their way through the crowd in search of stalls with fresh vegetables and reasonable prices.

If anything, there seemed to be even more people at the bazaar than usual—and there was a distinct sour note of panic in the air. News of the patrols had clearly passed from household to household with its usual speed.

People were afraid.

Three months ago, an important Parijati merchant had been murdered in his bed, his throat slit, his body dumped in front of the temple of the mothers of flame just before the dawn prayers. For an entire two weeks after that, the regent’s men had patrolled the streets on foot and on horseback, beating or arresting Ahiranyi suspected of rebellious activity and destroying any market stalls that had tried to remain open in defiance of the regent’s strict orders.

The Parijatdvipan merchants had refused to supply Hiranaprastha with rice and grain in the weeks that followed. Ahiranyi had starved.

Now it looked as though it was happening again. It was natural for people to remember and fear; remember, and scramble to buy what supplies they could before the markets were forcibly closed once more.

Priya wondered who had been murdered this time, listening for any names as she dove into the mass of people, toward the green banner on staves in the distance that marked the apothecary’s stall. She passed tables groaning under stacks of vegetables and sweet fruit, bolts of silky cloth and gracefully carved idols of the yaksa for family shrines, vats of golden oil and ghee. Even in the faint early-morning light, the market was vibrant with color and noise.

The press of people grew more painful.

She was nearly to the stall, caught in a sea of heaving, sweating bodies, when a man behind her cursed and pushed her out of the way. He shoved her hard with his full body weight, his palm heavy on her arm, unbalancing her entirely. Three people around her were knocked back. In the sudden release of pressure, she tumbled down onto the ground, feet skidding in the wet soil.

The bazaar was open to the air, and the dirt had been churned into a froth by feet and carts and the night’s monsoon rainfall. She felt the wetness seep in through her sari, from hem to thigh, soaking through draped cotton to the petticoat underneath. The man who had shoved her stumbled into her; if she hadn’t snatched her calf swiftly back, the pressure of his boot on her leg would have been agonizing. He glanced down at her—blank, dismissive, a faint sneer to his mouth—and looked away again.

Her mind went quiet.

In the silence, a single voice whispered, You could make him regret that.

There were gaps in Priya’s childhood memories, spaces big enough to stick a fist through. But whenever pain was inflicted on her—the humiliation of a blow, a man’s careless shove, a fellow servant’s cruel laughter—she felt the knowledge of how to cause equal suffering unfurl in her mind. Ghostly whispers, in her brother’s patient voice.

This is how you pinch a nerve hard enough to break a handhold. This is how you snap a bone. This is how you gouge an eye. Watch carefully, Priya. Just like this.

This is how you stab someone through the heart.

She carried a knife at her waist. It was a very good knife, practical, with a plain sheath and hilt, and she kept its edge finely honed for kitchen work. With nothing but her little knife and a careful slide of her finger and thumb, she could leave the insides of anything—vegetables, unskinned meat, fruits newly harvested from the regent’s orchard—swiftly bared, the outer rind a smooth, coiled husk in her palm.

She looked back up at the man and carefully let the thought of her knife drift away. She unclenched her trembling fingers.

You’re lucky, she thought, that I am not what I was raised to be.

The crowd behind her and in front of her was growing thicker. Priya couldn’t even see the green banner of the apothecary’s stall any longer. She rocked back on the balls of her feet, then rose swiftly. Without looking at the man again, she angled herself and slipped between two strangers in front of her, putting her small stature to good use and shoving her way to the front of the throng. A judicious application of her elbows and knees and some wriggling finally brought her near enough to the stall to see the apothecary’s face, puckered with sweat and irritation.

The stall was a mess, vials turned on their sides, clay pots upended. The apothecary was packing away his wares as fast as he could. Behind her, around her, she could hear the rumbling noise of the crowd grow more tense.

“Please,” she said loudly. “Uncle, please. If you’ve got any beads of sacred wood to spare, I’ll buy them from you.”

A stranger to her left snorted audibly. “You think he’s got any left? Brother, if you do, I’ll pay double whatever she offers.”

“My grandmother’s sick,” a girl shouted, three people deep behind them. “So if you could help me out, uncle—”

Priya felt the wood of the stall begin to peel beneath the hard pressure of her nails.

“Please,” she said, her voice pitched low to cut across the din.

But the apothecary’s attention was raised toward the back of the crowd. Priya didn’t have to turn her own head to know he’d caught sight of the white-and-gold uniforms of the regent’s men, finally here to close the bazaar.

“I’m closed up,” he shouted out. “There’s nothing more for any of you. Get lost!” He slammed his hand down, then shoved the last of his wares away with a shake of his head.

The crowd began to disperse slowly. A few people stayed, still pleading for the apothecary’s aid, but Priya didn’t join them. She knew she would get nothing here.

She turned and threaded her way back out of the crowd, stopping only to buy a small bag of kachoris from a tired-eyed vendor. Her sodden petticoat stuck heavily to her legs. She plucked the cloth, pulling it from her thighs, and strode in the opposite direction of the soldiers.

On the farthest edge of the market, where the last of the stalls and well-trod ground met the main road leading to open farmland and scattered villages beyond, was a dumping ground. The locals had built a brick wall around it, but that did nothing to contain the stench of it. Food sellers threw their stale oil and decayed produce here, and sometimes discarded any cooked food that couldn’t be sold.

When Priya had been much younger she’d known this place well. She’d known exactly the nausea and euphoria that finding something near rotten but edible could send spiraling through a starving body. Even now, her stomach lurched strangely at the sight of the heap, the familiar, thick stench of it rising around her.

Today, there were six figures huddled against its walls in the meager shade. Five young boys and a girl of about fifteen—older than the rest.

Knowledge was shared between the children who lived alone in the city, the ones who drifted from market to market, sleeping on the verandas of kinder households. They whispered to each other the best spots for begging for alms or collecting scraps. They passed word of which stallholders would give them food out of pity, and which would beat them with a stick sooner than offer even an ounce of charity.

They told each other about Priya, too.

If you go to the Old Bazaar on the first morning after rest day, a maid will come and give you sacred wood, if you need it. She won’t ask you for coin or favors. She’ll just help. No, she really will. She won’t ask for anything at all.

The girl looked up at Priya. Her left eyelid was speckled with faint motes of green, like algae on still water. She wore a thread around her throat, a single bead of wood strung upon it.

“Soldiers are out,” the girl said by way of greeting. A few of the boys shifted restlessly, looking over her shoulder at the tumult of the market. Some wore shawls to hide the rot on their necks and arms—the veins of green, the budding of new roots under skin.

“They are. All over the city,” Priya agreed.

“Did a merchant get his head chopped off again?”

Priya shook her head. “I know as much as you do.”

The girl looked from Priya’s face down to Priya’s muddied sari, her hands empty apart from the sack of kachoris. There was a question in her gaze.

“I couldn’t get any beads today,” Priya confirmed. She watched the girl’s expression crumple, though she valiantly tried to control it. Sympathy would do her no good, so Priya offered the pastries out instead. “You should go now. You don’t want to get caught by the guards.”

The children snatched the kachoris up, a few muttering their thanks, and scattered. The girl rubbed the bead at her throat with her knuckles as she went. Priya knew it would be cold under her hand—empty of magic.

If the girl didn’t get hold of more sacred wood soon, then the next time Priya saw her, the left side of her face would likely be as green-dusted as her eyelid.

You can’t save them all, she reminded herself. You’re no one. This is all you can do. This, and no more.

Priya turned back to leave—and saw that one boy had hung back, waiting patiently for her to notice him. He was the kind of small that suggested malnourishment; his bones too sharp, his head too large for a body that hadn’t yet grown to match it. He had his shawl over his hair, but she could still see his dark curls, and the deep green leaves growing between them. He’d wrapped his hands up in cloth.

“Do you really have nothing, ma’am?” he asked hesitantly.

“Really,” Priya said. “If I had any sacred wood, I’d have given it to you.”

“I thought maybe you lied,” he said. “I thought, maybe you haven’t got enough for more than one person, and you didn’t want to make anyone feel bad. But there’s only me now. So you can help me.”

“I really am sorry,” Priya said. She could hear yelling and footsteps echoing from the market, the crash of wood as stalls were closed up.

The boy looked like he was mustering up his courage. And sure enough, after a moment, he squared his shoulders and said, “If you can’t get me any sacred wood, then can you get me a job?”

She blinked at him, surprised.

“I—I’m just a maidservant,” she said. “I’m sorry, little brother, but—”

“You must work in a nice house, if you can help strays like us,” he said quickly. “A big house with money to spare. Maybe your masters need a boy who works hard and doesn’t make much trouble? That could be me.”

“Most households won’t take a boy who has the rot, no matter how hardworking he is,” she pointed out gently, trying to lessen the blow of her words.

“I know,” he said. His jaw was set, stubborn. “But I’m still asking.”

Smart boy. She couldn’t blame him for taking the chance. She was clearly soft enough to spend her own coin on sacred wood to help the rot-riven. Why wouldn’t he push her for more?

“I’ll do anything anyone needs me to do,” he insisted. “Ma’am, I can clean latrines. I can cut wood. I can work land. My family is—they were—farmers. I’m not afraid of hard work.”

“You haven’t got anyone?” she asked. “None of the others look out for you?” She gestured in the vague direction the other children had vanished.

“I’m alone,” he said simply. Then: “Please.”

A few people drifted past them, carefully skirting the boy. His wrapped hands, the shawl over his head—both revealed his rot-riven status just as well as anything they hid would have.

“Call me Priya,” she said. “Not ma’am.”

“Priya,” he repeated obediently.

“You say you can work,” she said. She looked at his hands. “How bad are they?”

“Not that bad.”

“Show me,” she said. “Give me your wrist.”

“You don’t mind touching me?” he asked. There was a slight waver of hesitation in his voice.

“Rot can’t pass between people,” she said. “Unless I pluck one of those leaves from your hair and eat it, I think I’ll be fine.”

That brought a smile to his face. There for a blink, like a flash of sun through parting clouds, then gone. He deftly unwrapped one of his hands. She took hold of his wrist and raised it up to the light.

There was a little bud, growing up under the skin.

It was pressing against the flesh of his fingertip, his finger a too-small shell for the thing trying to unfurl. She looked at the tracery of green visible through the thin skin at the back of his hand, the fine lace of it. The bud had deep roots.

She swallowed. Ah. Deep roots, deep rot. If he already had leaves in his hair, green spidering through his blood, she couldn’t imagine that he had long left.

“Come with me,” she said, and tugged him by the wrist, making him follow her. She walked along the road, eventually joining the flow of the crowd leaving the market behind.

“Where are we going?” he asked. He didn’t try to pull away from her.

“I’m going to get you some sacred wood,” she said determinedly, putting all thoughts of murders and soldiers and the work she needed to do out of her mind. She released him and strode ahead. He ran to keep up with her, dragging his dirty shawl tight around his thin frame. “And after that, we’ll see what to do with you.”

The grandest of the city’s pleasure houses lined the edges of the river. It was early enough in the day that they were utterly quiet, their pink lanterns unlit. But they would be busy later. The brothels were always left well alone by the regent’s men. Even in the height of the last boiling summer, before the monsoon had cracked the heat in two, when the rebel sympathizers had been singing anti-imperialist songs and a noble lord’s chariot had been cornered and burned on the street directly outside his own haveli—the brothels had kept their lamps lit.

Too many of the pleasure houses belonged to highborn nobles for the regent to close them. Too many were patronized by visiting merchants and nobility from Parijatdvipa’s other city-states—a source of income no one seemed to want to do without.

To the rest of Parijatdvipa, Ahiranya was a den of vice, good for pleasure and little else. It carried its bitter history, its status as the losing side of an ancient war, like a yoke. They called it a backward place, rife with political violence, and, in more recent years, with the rot: the strange disease that twisted plants and crops and infected the men and women who worked the fields and forests with flowers that sprouted through the skin and leaves that pushed through their eyes. As the rot grew, other sources of income in Ahiranya had dwindled. And unrest had surged and swelled until Priya feared it too would crack, with all the fury of a storm.

As Priya and the boy walked on, the pleasure houses grew less grand. Soon, there were no pleasure houses at all. Around her were cramped homes, small shops. Ahead of her lay the edge of the forest. Even in the morning light, it was shadowed, the trees a silent barrier of green.

Priya had never met anyone born and raised outside Ahiranya who was not disturbed by the quiet of the forest. She’d known maids raised in Alor or even neighboring Srugna who avoided the place entirely. “There should be noise,” they’d mutter. “Birdsong. Or insects. It isn’t natural.”

But the heavy quiet was comforting to Priya. She was Ahiranyi to the bone. She liked the silence of it, broken only by the scuff of her own feet against the ground.

“Wait for me here,” she told the boy. “I won’t be long.”

He nodded without saying a word. He was staring out at the forest when she left him, a faint breeze rustling the leaves of his hair.

Priya slipped down a narrow street where the ground was uneven with hidden tree roots, the dirt rising and falling in mounds beneath her feet. Ahead of her was a single dwelling. Beneath its pillared veranda crouched an older man.

He raised his head as she approached. At first he seemed to look right through her, as though he’d been expecting someone else entirely. Then his gaze focused. His eyes narrowed in recognition.

“You,” he said.

“Gautam.” She tilted her head in a gesture of respect. “How are you?”

“Busy,” he said shortly. “Why are you here?”

“I need sacred wood. Just one bead.”

“Should have gone to the bazaar, then,” he said evenly. “I’ve supplied plenty of apothecaries. They can deal with you.”

“I tried the Old Bazaar. No one has anything.”

“If they don’t, why do you think I will?”

Oh, come on now, she thought, irritated. But she said nothing. She waited until his nostrils flared as he huffed and rose up from the veranda, turning to the beaded curtain of the doorway. Tucked in the back of his tunic was a heavy hand sickle.

“Fine. Come in, then. The sooner we do this, the sooner you leave.”

She drew the purse from her blouse before climbing up the steps and entering after him.

He led her to his workroom and bid her to stand by the table at its center. Cloth sacks lined the corners of the room. Small stoppered bottles—innumerable salves and tinctures and herbs harvested from the forest itself—sat in tidy rows on shelves. The air smelled of earth and damp.

He took her entire purse from her, opened the drawstring, and adjusted its weight in his palm. Then he clucked, tongue against teeth, and dropped it onto the table.

“This isn’t enough.”

“You—of course it’s enough,” Priya said. “That’s all the money I have.”

“That doesn’t magically make it enough.”

“That’s what it cost me at the bazaar last time—”

“But you couldn’t get anything at the bazaar,” said Gautam. “And had you been able to, he would have charged you more. Supply is low, demand is high.” He frowned at her sourly. “You think it’s easy harvesting sacred wood?”

“Not at all,” Priya said. Be pleasant, she reminded herself. You need his help.

“Last month I sent in four woodcutters. They came out after two days, thinking they’d been in there two hours. Between—that,” he said, gesturing in the direction of the forest, “and the regent flinging his thugs all over the fucking city for who knows what reason, you think it’s easy work?”

“No,” Priya said. “I’m sorry.”

But he wasn’t done quite yet.

“I’m still waiting for the men I sent this week to come back,” he went on. His fingers were tapping on the table’s surface—a fast, irritated rhythm. “Who knows when that will be? I have plenty of reason to get the best price for the supplies I have. So I’ll have a proper payment from you, girl, or you’ll get nothing.”

Before he could continue, she lifted her hand. She had a few bracelets on her wrists. Two were good-quality metal. She slipped them off, placing them on the table before him, alongside the purse.

“The money and these,” she said. “That’s all I have.”

She thought he’d refuse her, just out of spite. But instead, he scooped up the bangles and the coin and pocketed them.

“That’ll do. Now watch,” he said. “I’ll show you a trick.”

He threw a cloth package down on the table. It was tied with a rope. He drew it open with one swift tug, letting the cloth fall to the sides.

Priya flinched back.

Inside lay the severed branch of a young tree. The bark had split, pale wood opening up into a red-brown wound. The sap that oozed from its surface was the color and consistency of blood.

“This came from the path leading to the grove my men usually harvest,” he said. “They wanted to show me why they couldn’t fulfill the regular quota. Rot as far as the eye could see, they told me.” His own eyes were hooded. “You can look closer if you want.”

“No, thank you,” Priya said tightly.

“Sure?”

“You should burn it,” she said. She was doing her best not to breathe the scent of it in too deeply. It had a stench like meat.

He snorted. “It has its uses.” He walked away from her, rooting through his shelves. After a moment, he returned with another cloth-wrapped item, this one only as large as a fingertip. He unwrapped it, careful to keep from touching what it held. Priya could feel the heat rising from the wood within: a strange, pulsing warmth that rolled off its surface with the steadiness of a sunbeam.

Sacred wood.

She watched as Gautam held the shard close to the rot-struck branch, as the lesion on the branch paled, the redness fading. The stench of it eased a little, and Priya breathed gratefully.

“There,” he said. “Now you know it is fresh. You’ll get plenty of use from it.”

“Thank you. That was a useful demonstration.” She tried not to let her impatience show. What did he want—awe? Tears of gratitude? She had no time for any of it. “You should still burn the branch. If you touch it by mistake…”

“I know how to handle the rot. I send men into the forest every day,” he said dismissively. “And what do you do? Sweep floors? I don’t need your advice.”

He thrust the shard of sacred wood out to her. “Take this. And leave.”

She bit her tongue and held out her hand, the long end of her sari drawn over her palm. She rewrapped the sliver of wood up carefully, once, twice, tightening the fabric, tying it off with a neat knot. Gautam watched her.

“Whoever you’re buying this for, the rot is still going to kill them,” he said, when she was done. “This branch will die even if I wrap it in a whole shell of sacred wood. It will just die slower. My professional opinion for you, at no extra cost.” He threw the cloth back over the infected branch with one careless flick of his fingers. “So don’t come back here and waste your money again. I’ll show you out.”

He shepherded her to the door. She pushed through the beaded curtain, greedily inhaling the clean air, untainted by the smell of decay.

At the edge of the veranda there was a shrine alcove carved into the wall. Inside it were three idols sculpted from plain wood, with lustrous black eyes and hair of vines. Before them were three tiny clay lamps lit with cloth wicks set in pools of oil. Sacred numbers.

She remembered how perfectly she’d once been able to fit her whole body into that alcove. She’d slept in it one night, curled up tight. She’d been as small as the orphan boy, once.

“Do you still let beggars shelter on your veranda when it rains?” Priya asked, turning to look at Gautam where he stood, barring the entryway.

“Beggars are bad for business,” he said. “And the ones I see these days don’t have brothers I owe favors to. Are you leaving or not?”

Just the threat of pain can break someone. She briefly met Gautam’s eyes. Something impatient and malicious lurked there. A knife, used right, never has to draw blood.

But ah, Priya didn’t have it in her to even threaten this old bully. She stepped back.

What a big void there was, between the knowledge within her and the person she appeared to be, bowing her head in respect to a petty man who still saw her as a street beggar who’d risen too far, and hated her for it.

“Thank you, Gautam,” she said. “I’ll try not to trouble you again.”

She’d have to carve the wood herself. She couldn’t give the

The fragrance of the gardens drifted in through the high windows—sweet roses, and even sweeter imperial needle-flower, pale and fragile, growing in such thick profusion that it poured in through the lattice, its white petals unfurled against the sandstone walls. The priests flung petals on the pyre, murmuring prayers as the servants carried in wood and arranged it carefully, applying camphor and ghee, scattering drops of perfumed oil.

On his throne, Emperor Chandra murmured along with his priests. In his hands, he held a string of prayer stones, each an acorn seeded with the name of a mother of flame: Divyanshi, Ahamara, Nanvishi, Suhana, Meenakshi. As he recited, his courtiers—the kings of Parijatdvipa’s city-states, their princely sons, their bravest warriors—recited along with him. Only the king of Alor and his brood of nameless sons were notably, pointedly, silent.

Emperor Chandra’s sister was brought into the court.

Her ladies-in-waiting stood on either side of her. To her left, a nameless princess of Alor, commonly referred to only as Alori; to her right, a high-blooded lady, Narina, daughter of a notable mathematician from Srugna and a highborn Parijati mother. The ladies-in-waiting wore red, bloody and bridal. In their hair, they wore crowns of kindling, bound with thread to mimic stars. As they entered the room, the watching men bowed, pressing their faces to the floor, their palms flat on the marble. The women had been dressed with reverence, marked with blessed water, prayed over for a day and a night until dawn had touched the sky. They were as holy as women could be.

Chandra did not bow his head. He watched his sister.

She wore no crown. Her hair was loose—tangled, trailing across her shoulders. He had sent maids to prepare her, but she had denied them all, gnashing her teeth and weeping. He had sent her a sari of crimson, embroidered in the finest Dwarali gold, scented with needle-flower and perfume. She had refused it, choosing instead to wear palest mourning white. He had ordered the cooks to lace her food with opium, but she had refused to eat. She had not been blessed. She stood in the court, her head unadorned and her hair wild, like a living curse.

His sister was a fool and a petulant child. They would not be here, he reminded himself, if she had not proven herself thoroughly unwomanly. If she had not tried to ruin it all.

The head priest kissed the nameless princess upon the forehead. He did the same to Lady Narina. When he reached for Chandra’s sister, she flinched, turning her cheek.

The priest stepped back. His gaze—and his voice—was tranquil.

“You may rise,” he said. “Rise, and become mothers of flame.”

His sister took her ladies’ hands. She clasped them tight. They stood, the three of them, for a long moment, simply holding one another. Then his sister released them.

The ladies walked to the pyre and rose to its zenith. They kneeled.

His sister remained where she was. She stood with her head raised. A breeze blew needle-flower into her hair—white upon deepest black.

“Princess Malini,” said the head priest. “You may rise.”

She shook her head wordlessly.

Rise, Chandra thought. I have been more merciful than you deserve, and we both know it.

Rise, sister.

“It is your choice,” the priest said. “We will not compel you. Will you forsake immortality, or will you rise?”

The offer was a straightforward one. But she did not move. She shook her head once more. She was weeping, silently, her face otherwise devoid of feeling.

The priest nodded.

“Then we begin,” he said.

Chandra stood. The prayer stones clinked as he released them.

Of course it had come to this.

He stepped down from his throne. He crossed the court, before a sea of bowing men. He took his sister by the shoulders, ever so gentle.

“Do not be afraid,” he told her. “You are proving your purity. You are saving your name. Your honor. Now. Rise.”

One of the priests had lit a torch. The scent of burning and camphor filled the court. The priests began to sing, a low song that filled the air, swelled within it. They would not wait for his sister.

But there was still time. The pyre had not yet been lit.

As his sister shook her head once more, he grasped her by the skull, raising her face up.

He did not hold her tight. He did not harm her. He was not a monster.

“Remember,” he said, voice low, nearly drowned out by the sonorous song, “that you have brought this upon yourself. Remember that you have betrayed your family and denied your name. If you do not rise… sister, remember that you have chosen to ruin yourself, and I have done all in my power to help you. Remember that.”

The priest touched his torch to the pyre. The wood, slowly, began to burn.

Firelight reflected in her eyes. She looked at him with a face like a mirror: blank of feeling, reflecting nothing back at him but their shared dark eyes and serious brows. Their shared blood and shared bone.

“My brother,” she said. “I will not forget.”

Someone important must have been killed in the night.

Priya was sure of it the minute she heard the thud of hooves on the road behind her. She stepped to the roadside as a group of guards clad in Parijati white and gold raced past her on their horses, their sabers clinking against their embossed belts. She drew her pallu over her face—partly because they would expect such a gesture of respect from a common woman, and partly to avoid the risk that one of them would recognize her—and watched them through the gap between her fingers and the cloth.

When they were out of sight, she didn’t run. But she did start walking very, very fast. The sky was already transforming from milky gray to the pearly blue of dawn, and she still had a long way to go.

The Old Bazaar was on the outskirts of the city. It was far enough from the regent’s mahal that Priya had a vague hope it wouldn’t have been shut yet. And today, she was lucky. As she arrived, breathless, sweat dampening the back of her blouse, she could see that the streets were still seething with people: parents tugging along small children; traders carrying large sacks of flour or rice on their heads; gaunt beggars, skirting the edges of the market with their alms bowls in hand; and women like Priya, plain ordinary women in even plainer saris, stubbornly shoving their way through the crowd in search of stalls with fresh vegetables and reasonable prices.

If anything, there seemed to be even more people at the bazaar than usual—and there was a distinct sour note of panic in the air. News of the patrols had clearly passed from household to household with its usual speed.

People were afraid.

Three months ago, an important Parijati merchant had been murdered in his bed, his throat slit, his body dumped in front of the temple of the mothers of flame just before the dawn prayers. For an entire two weeks after that, the regent’s men had patrolled the streets on foot and on horseback, beating or arresting Ahiranyi suspected of rebellious activity and destroying any market stalls that had tried to remain open in defiance of the regent’s strict orders.

The Parijatdvipan merchants had refused to supply Hiranaprastha with rice and grain in the weeks that followed. Ahiranyi had starved.

Now it looked as though it was happening again. It was natural for people to remember and fear; remember, and scramble to buy what supplies they could before the markets were forcibly closed once more.

Priya wondered who had been murdered this time, listening for any names as she dove into the mass of people, toward the green banner on staves in the distance that marked the apothecary’s stall. She passed tables groaning under stacks of vegetables and sweet fruit, bolts of silky cloth and gracefully carved idols of the yaksa for family shrines, vats of golden oil and ghee. Even in the faint early-morning light, the market was vibrant with color and noise.

The press of people grew more painful.

She was nearly to the stall, caught in a sea of heaving, sweating bodies, when a man behind her cursed and pushed her out of the way. He shoved her hard with his full body weight, his palm heavy on her arm, unbalancing her entirely. Three people around her were knocked back. In the sudden release of pressure, she tumbled down onto the ground, feet skidding in the wet soil.

The bazaar was open to the air, and the dirt had been churned into a froth by feet and carts and the night’s monsoon rainfall. She felt the wetness seep in through her sari, from hem to thigh, soaking through draped cotton to the petticoat underneath. The man who had shoved her stumbled into her; if she hadn’t snatched her calf swiftly back, the pressure of his boot on her leg would have been agonizing. He glanced down at her—blank, dismissive, a faint sneer to his mouth—and looked away again.

Her mind went quiet.

In the silence, a single voice whispered, You could make him regret that.

There were gaps in Priya’s childhood memories, spaces big enough to stick a fist through. But whenever pain was inflicted on her—the humiliation of a blow, a man’s careless shove, a fellow servant’s cruel laughter—she felt the knowledge of how to cause equal suffering unfurl in her mind. Ghostly whispers, in her brother’s patient voice.

This is how you pinch a nerve hard enough to break a handhold. This is how you snap a bone. This is how you gouge an eye. Watch carefully, Priya. Just like this.

This is how you stab someone through the heart.

She carried a knife at her waist. It was a very good knife, practical, with a plain sheath and hilt, and she kept its edge finely honed for kitchen work. With nothing but her little knife and a careful slide of her finger and thumb, she could leave the insides of anything—vegetables, unskinned meat, fruits newly harvested from the regent’s orchard—swiftly bared, the outer rind a smooth, coiled husk in her palm.

She looked back up at the man and carefully let the thought of her knife drift away. She unclenched her trembling fingers.

You’re lucky, she thought, that I am not what I was raised to be.

The crowd behind her and in front of her was growing thicker. Priya couldn’t even see the green banner of the apothecary’s stall any longer. She rocked back on the balls of her feet, then rose swiftly. Without looking at the man again, she angled herself and slipped between two strangers in front of her, putting her small stature to good use and shoving her way to the front of the throng. A judicious application of her elbows and knees and some wriggling finally brought her near enough to the stall to see the apothecary’s face, puckered with sweat and irritation.

The stall was a mess, vials turned on their sides, clay pots upended. The apothecary was packing away his wares as fast as he could. Behind her, around her, she could hear the rumbling noise of the crowd grow more tense.

“Please,” she said loudly. “Uncle, please. If you’ve got any beads of sacred wood to spare, I’ll buy them from you.”

A stranger to her left snorted audibly. “You think he’s got any left? Brother, if you do, I’ll pay double whatever she offers.”

“My grandmother’s sick,” a girl shouted, three people deep behind them. “So if you could help me out, uncle—”

Priya felt the wood of the stall begin to peel beneath the hard pressure of her nails.

“Please,” she said, her voice pitched low to cut across the din.

But the apothecary’s attention was raised toward the back of the crowd. Priya didn’t have to turn her own head to know he’d caught sight of the white-and-gold uniforms of the regent’s men, finally here to close the bazaar.

“I’m closed up,” he shouted out. “There’s nothing more for any of you. Get lost!” He slammed his hand down, then shoved the last of his wares away with a shake of his head.

The crowd began to disperse slowly. A few people stayed, still pleading for the apothecary’s aid, but Priya didn’t join them. She knew she would get nothing here.

She turned and threaded her way back out of the crowd, stopping only to buy a small bag of kachoris from a tired-eyed vendor. Her sodden petticoat stuck heavily to her legs. She plucked the cloth, pulling it from her thighs, and strode in the opposite direction of the soldiers.

On the farthest edge of the market, where the last of the stalls and well-trod ground met the main road leading to open farmland and scattered villages beyond, was a dumping ground. The locals had built a brick wall around it, but that did nothing to contain the stench of it. Food sellers threw their stale oil and decayed produce here, and sometimes discarded any cooked food that couldn’t be sold.

When Priya had been much younger she’d known this place well. She’d known exactly the nausea and euphoria that finding something near rotten but edible could send spiraling through a starving body. Even now, her stomach lurched strangely at the sight of the heap, the familiar, thick stench of it rising around her.

Today, there were six figures huddled against its walls in the meager shade. Five young boys and a girl of about fifteen—older than the rest.

Knowledge was shared between the children who lived alone in the city, the ones who drifted from market to market, sleeping on the verandas of kinder households. They whispered to each other the best spots for begging for alms or collecting scraps. They passed word of which stallholders would give them food out of pity, and which would beat them with a stick sooner than offer even an ounce of charity.

They told each other about Priya, too.

If you go to the Old Bazaar on the first morning after rest day, a maid will come and give you sacred wood, if you need it. She won’t ask you for coin or favors. She’ll just help. No, she really will. She won’t ask for anything at all.

The girl looked up at Priya. Her left eyelid was speckled with faint motes of green, like algae on still water. She wore a thread around her throat, a single bead of wood strung upon it.

“Soldiers are out,” the girl said by way of greeting. A few of the boys shifted restlessly, looking over her shoulder at the tumult of the market. Some wore shawls to hide the rot on their necks and arms—the veins of green, the budding of new roots under skin.

“They are. All over the city,” Priya agreed.

“Did a merchant get his head chopped off again?”

Priya shook her head. “I know as much as you do.”

The girl looked from Priya’s face down to Priya’s muddied sari, her hands empty apart from the sack of kachoris. There was a question in her gaze.

“I couldn’t get any beads today,” Priya confirmed. She watched the girl’s expression crumple, though she valiantly tried to control it. Sympathy would do her no good, so Priya offered the pastries out instead. “You should go now. You don’t want to get caught by the guards.”

The children snatched the kachoris up, a few muttering their thanks, and scattered. The girl rubbed the bead at her throat with her knuckles as she went. Priya knew it would be cold under her hand—empty of magic.

If the girl didn’t get hold of more sacred wood soon, then the next time Priya saw her, the left side of her face would likely be as green-dusted as her eyelid.

You can’t save them all, she reminded herself. You’re no one. This is all you can do. This, and no more.

Priya turned back to leave—and saw that one boy had hung back, waiting patiently for her to notice him. He was the kind of small that suggested malnourishment; his bones too sharp, his head too large for a body that hadn’t yet grown to match it. He had his shawl over his hair, but she could still see his dark curls, and the deep green leaves growing between them. He’d wrapped his hands up in cloth.

“Do you really have nothing, ma’am?” he asked hesitantly.

“Really,” Priya said. “If I had any sacred wood, I’d have given it to you.”

“I thought maybe you lied,” he said. “I thought, maybe you haven’t got enough for more than one person, and you didn’t want to make anyone feel bad. But there’s only me now. So you can help me.”

“I really am sorry,” Priya said. She could hear yelling and footsteps echoing from the market, the crash of wood as stalls were closed up.

The boy looked like he was mustering up his courage. And sure enough, after a moment, he squared his shoulders and said, “If you can’t get me any sacred wood, then can you get me a job?”

She blinked at him, surprised.

“I—I’m just a maidservant,” she said. “I’m sorry, little brother, but—”

“You must work in a nice house, if you can help strays like us,” he said quickly. “A big house with money to spare. Maybe your masters need a boy who works hard and doesn’t make much trouble? That could be me.”

“Most households won’t take a boy who has the rot, no matter how hardworking he is,” she pointed out gently, trying to lessen the blow of her words.

“I know,” he said. His jaw was set, stubborn. “But I’m still asking.”

Smart boy. She couldn’t blame him for taking the chance. She was clearly soft enough to spend her own coin on sacred wood to help the rot-riven. Why wouldn’t he push her for more?

“I’ll do anything anyone needs me to do,” he insisted. “Ma’am, I can clean latrines. I can cut wood. I can work land. My family is—they were—farmers. I’m not afraid of hard work.”

“You haven’t got anyone?” she asked. “None of the others look out for you?” She gestured in the vague direction the other children had vanished.

“I’m alone,” he said simply. Then: “Please.”

A few people drifted past them, carefully skirting the boy. His wrapped hands, the shawl over his head—both revealed his rot-riven status just as well as anything they hid would have.

“Call me Priya,” she said. “Not ma’am.”

“Priya,” he repeated obediently.

“You say you can work,” she said. She looked at his hands. “How bad are they?”

“Not that bad.”

“Show me,” she said. “Give me your wrist.”

“You don’t mind touching me?” he asked. There was a slight waver of hesitation in his voice.

“Rot can’t pass between people,” she said. “Unless I pluck one of those leaves from your hair and eat it, I think I’ll be fine.”

That brought a smile to his face. There for a blink, like a flash of sun through parting clouds, then gone. He deftly unwrapped one of his hands. She took hold of his wrist and raised it up to the light.

There was a little bud, growing up under the skin.

It was pressing against the flesh of his fingertip, his finger a too-small shell for the thing trying to unfurl. She looked at the tracery of green visible through the thin skin at the back of his hand, the fine lace of it. The bud had deep roots.

She swallowed. Ah. Deep roots, deep rot. If he already had leaves in his hair, green spidering through his blood, she couldn’t imagine that he had long left.

“Come with me,” she said, and tugged him by the wrist, making him follow her. She walked along the road, eventually joining the flow of the crowd leaving the market behind.

“Where are we going?” he asked. He didn’t try to pull away from her.

“I’m going to get you some sacred wood,” she said determinedly, putting all thoughts of murders and soldiers and the work she needed to do out of her mind. She released him and strode ahead. He ran to keep up with her, dragging his dirty shawl tight around his thin frame. “And after that, we’ll see what to do with you.”

The grandest of the city’s pleasure houses lined the edges of the river. It was early enough in the day that they were utterly quiet, their pink lanterns unlit. But they would be busy later. The brothels were always left well alone by the regent’s men. Even in the height of the last boiling summer, before the monsoon had cracked the heat in two, when the rebel sympathizers had been singing anti-imperialist songs and a noble lord’s chariot had been cornered and burned on the street directly outside his own haveli—the brothels had kept their lamps lit.

Too many of the pleasure houses belonged to highborn nobles for the regent to close them. Too many were patronized by visiting merchants and nobility from Parijatdvipa’s other city-states—a source of income no one seemed to want to do without.

To the rest of Parijatdvipa, Ahiranya was a den of vice, good for pleasure and little else. It carried its bitter history, its status as the losing side of an ancient war, like a yoke. They called it a backward place, rife with political violence, and, in more recent years, with the rot: the strange disease that twisted plants and crops and infected the men and women who worked the fields and forests with flowers that sprouted through the skin and leaves that pushed through their eyes. As the rot grew, other sources of income in Ahiranya had dwindled. And unrest had surged and swelled until Priya feared it too would crack, with all the fury of a storm.

As Priya and the boy walked on, the pleasure houses grew less grand. Soon, there were no pleasure houses at all. Around her were cramped homes, small shops. Ahead of her lay the edge of the forest. Even in the morning light, it was shadowed, the trees a silent barrier of green.

Priya had never met anyone born and raised outside Ahiranya who was not disturbed by the quiet of the forest. She’d known maids raised in Alor or even neighboring Srugna who avoided the place entirely. “There should be noise,” they’d mutter. “Birdsong. Or insects. It isn’t natural.”

But the heavy quiet was comforting to Priya. She was Ahiranyi to the bone. She liked the silence of it, broken only by the scuff of her own feet against the ground.

“Wait for me here,” she told the boy. “I won’t be long.”

He nodded without saying a word. He was staring out at the forest when she left him, a faint breeze rustling the leaves of his hair.

Priya slipped down a narrow street where the ground was uneven with hidden tree roots, the dirt rising and falling in mounds beneath her feet. Ahead of her was a single dwelling. Beneath its pillared veranda crouched an older man.

He raised his head as she approached. At first he seemed to look right through her, as though he’d been expecting someone else entirely. Then his gaze focused. His eyes narrowed in recognition.

“You,” he said.

“Gautam.” She tilted her head in a gesture of respect. “How are you?”

“Busy,” he said shortly. “Why are you here?”

“I need sacred wood. Just one bead.”

“Should have gone to the bazaar, then,” he said evenly. “I’ve supplied plenty of apothecaries. They can deal with you.”

“I tried the Old Bazaar. No one has anything.”

“If they don’t, why do you think I will?”

Oh, come on now, she thought, irritated. But she said nothing. She waited until his nostrils flared as he huffed and rose up from the veranda, turning to the beaded curtain of the doorway. Tucked in the back of his tunic was a heavy hand sickle.

“Fine. Come in, then. The sooner we do this, the sooner you leave.”

She drew the purse from her blouse before climbing up the steps and entering after him.

He led her to his workroom and bid her to stand by the table at its center. Cloth sacks lined the corners of the room. Small stoppered bottles—innumerable salves and tinctures and herbs harvested from the forest itself—sat in tidy rows on shelves. The air smelled of earth and damp.

He took her entire purse from her, opened the drawstring, and adjusted its weight in his palm. Then he clucked, tongue against teeth, and dropped it onto the table.

“This isn’t enough.”

“You—of course it’s enough,” Priya said. “That’s all the money I have.”

“That doesn’t magically make it enough.”

“That’s what it cost me at the bazaar last time—”

“But you couldn’t get anything at the bazaar,” said Gautam. “And had you been able to, he would have charged you more. Supply is low, demand is high.” He frowned at her sourly. “You think it’s easy harvesting sacred wood?”

“Not at all,” Priya said. Be pleasant, she reminded herself. You need his help.

“Last month I sent in four woodcutters. They came out after two days, thinking they’d been in there two hours. Between—that,” he said, gesturing in the direction of the forest, “and the regent flinging his thugs all over the fucking city for who knows what reason, you think it’s easy work?”

“No,” Priya said. “I’m sorry.”

But he wasn’t done quite yet.

“I’m still waiting for the men I sent this week to come back,” he went on. His fingers were tapping on the table’s surface—a fast, irritated rhythm. “Who knows when that will be? I have plenty of reason to get the best price for the supplies I have. So I’ll have a proper payment from you, girl, or you’ll get nothing.”

Before he could continue, she lifted her hand. She had a few bracelets on her wrists. Two were good-quality metal. She slipped them off, placing them on the table before him, alongside the purse.

“The money and these,” she said. “That’s all I have.”

She thought he’d refuse her, just out of spite. But instead, he scooped up the bangles and the coin and pocketed them.

“That’ll do. Now watch,” he said. “I’ll show you a trick.”

He threw a cloth package down on the table. It was tied with a rope. He drew it open with one swift tug, letting the cloth fall to the sides.

Priya flinched back.

Inside lay the severed branch of a young tree. The bark had split, pale wood opening up into a red-brown wound. The sap that oozed from its surface was the color and consistency of blood.

“This came from the path leading to the grove my men usually harvest,” he said. “They wanted to show me why they couldn’t fulfill the regular quota. Rot as far as the eye could see, they told me.” His own eyes were hooded. “You can look closer if you want.”

“No, thank you,” Priya said tightly.

“Sure?”

“You should burn it,” she said. She was doing her best not to breathe the scent of it in too deeply. It had a stench like meat.

He snorted. “It has its uses.” He walked away from her, rooting through his shelves. After a moment, he returned with another cloth-wrapped item, this one only as large as a fingertip. He unwrapped it, careful to keep from touching what it held. Priya could feel the heat rising from the wood within: a strange, pulsing warmth that rolled off its surface with the steadiness of a sunbeam.

Sacred wood.

She watched as Gautam held the shard close to the rot-struck branch, as the lesion on the branch paled, the redness fading. The stench of it eased a little, and Priya breathed gratefully.

“There,” he said. “Now you know it is fresh. You’ll get plenty of use from it.”

“Thank you. That was a useful demonstration.” She tried not to let her impatience show. What did he want—awe? Tears of gratitude? She had no time for any of it. “You should still burn the branch. If you touch it by mistake…”

“I know how to handle the rot. I send men into the forest every day,” he said dismissively. “And what do you do? Sweep floors? I don’t need your advice.”

He thrust the shard of sacred wood out to her. “Take this. And leave.”

She bit her tongue and held out her hand, the long end of her sari drawn over her palm. She rewrapped the sliver of wood up carefully, once, twice, tightening the fabric, tying it off with a neat knot. Gautam watched her.

“Whoever you’re buying this for, the rot is still going to kill them,” he said, when she was done. “This branch will die even if I wrap it in a whole shell of sacred wood. It will just die slower. My professional opinion for you, at no extra cost.” He threw the cloth back over the infected branch with one careless flick of his fingers. “So don’t come back here and waste your money again. I’ll show you out.”

He shepherded her to the door. She pushed through the beaded curtain, greedily inhaling the clean air, untainted by the smell of decay.

At the edge of the veranda there was a shrine alcove carved into the wall. Inside it were three idols sculpted from plain wood, with lustrous black eyes and hair of vines. Before them were three tiny clay lamps lit with cloth wicks set in pools of oil. Sacred numbers.

She remembered how perfectly she’d once been able to fit her whole body into that alcove. She’d slept in it one night, curled up tight. She’d been as small as the orphan boy, once.

“Do you still let beggars shelter on your veranda when it rains?” Priya asked, turning to look at Gautam where he stood, barring the entryway.

“Beggars are bad for business,” he said. “And the ones I see these days don’t have brothers I owe favors to. Are you leaving or not?”

Just the threat of pain can break someone. She briefly met Gautam’s eyes. Something impatient and malicious lurked there. A knife, used right, never has to draw blood.

But ah, Priya didn’t have it in her to even threaten this old bully. She stepped back.

What a big void there was, between the knowledge within her and the person she appeared to be, bowing her head in respect to a petty man who still saw her as a street beggar who’d risen too far, and hated her for it.

“Thank you, Gautam,” she said. “I’ll try not to trouble you again.”

She’d have to carve the wood herself. She couldn’t give the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved