- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

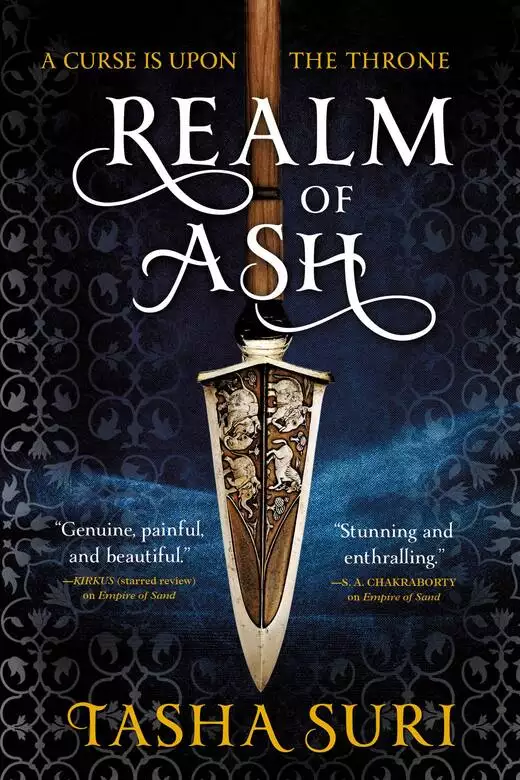

Some believe the Ambhan Empire is cursed. But Arwa doesn't simply believe it — she knows it's true.

Widowed by the infamous, unnatural massacre at Darez Fort, Arwa was saved only by the strangeness of her blood — a strangeness she had been taught all her life to suppress. She offers up her blood and service to the imperial family and makes common cause with a disgraced, illegitimate prince who has turned to forbidden occult arts to find a cure to the darkness hanging over the Empire.

Using the power in Arwa's blood, they seek answers in the realm of ash: a land where mortals can seek the ghostly echoes of their ancestors' dreams. But the Emperor's health is failing, and a terrible war of succession hovers on the horizon, not just for the imperial throne but for the magic underpinning Empire itself.

To save the Empire, Arwa and the prince must walk the bloody path of their shared past, through the realm of ash and into the desert, where the cause of the Empire's suffering — and its only chance of salvation — lie in wait.

But what they find there calls into question everything they've ever valued....and whether they want to save the Empire at all.

Release date: November 12, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Realm of Ash

Tasha Suri

—S. A. Chakraborty

“A brilliant debut that shows us a rich, magical world with clear parallels to this one: It has a sadistic leader with a cult-like following who warps the world for personal gain, a few individuals with the strength to resist him, and a planet seeking balance. But its core is a heroine defined by her choices, and her journey is absorbing, heart-wrenching, and triumphant. Highly recommended.”

—Kevin Hearne

“The best fantasy novel I have read this year. I loved it!”

—Miles Cameron

“Empire of Sand is astounding. The desert setting captured my imagination, the magic bound me up, and the epic story set my heart free.”

—Fran Wilde

“I was hooked from the moment I began Tasha Suri’s gorgeous debut novel, Empire of Sand. Suri has created a rich world full of beautiful and powerful magic, utterly compelling characters, high stakes, and immersive prose. I absolutely loved it!”

—Kat Howard

“A darkly intricate, devastating, and utterly original story about the ways we are bound by those we love.”

—R. F. Kuang

“A lush, atmospheric, and sweeping epic fantasy, a powerful story of resistance and love in the face of terrifying darkness. You’ll want to devour Empire of Sand.”

—Aliette de Bodard

“Genuine, painful, and beautiful. A very strong start for a new voice.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

“Complex, affecting epic fantasy.… Intricate worldbuilding, heartrending emotional stakes… well-wrought prose.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“The desert setting, complex characters, and epic mythology will captivate readers.”

—Booklist (starred review)

“This is the future of fantasy: rich, complex, unflinching. Empire of Sand is a stunning achievement.”

—Mark Oshiro

“Riveting and wonderful! A fascinating desert world, a compelling heroine, and a richly satisfying conclusion. Empire of Sand will sweep you away!”

—Sarah Beth Durst

“A lovely dark dream full of wrenching choices and bittersweet triumph. This gorgeous, magic-woven story and its determined heroine spin hope from hopelessness, power from powerlessness, and love from desolation.”

—Melissa Caruso

“Empire of Sand draws you into an intricately realized world of blood and secrets. An arresting and magical history told through the eyes of an indomitable heroine. I cannot ask for more.”

—Jeannette Ng

“An oasis of a story that you fall into, headfirst. A mesmerizing tale full of magic and mystery.”

—Sayantani DasGupta

“A powerful story of empire, magic, and resistance, told with an intimate poignancy and emotional resonance.”

—Rowenna Miller

Don’t be sick. Don’t be sick.

The palanquin jolted suddenly, tipping precariously forward. Arwa bit back a curse and gripped the edge of one varnished wooden panel. The curtain fluttered; she saw her maidservant reach for it hastily, holding it steady. Nuri’s eyes met her own through the crack between the curtain and the panel, soft with apology.

“I’m sorry, my lady,” said Nuri. “I’ll tie the curtain in place.”

“No need,” Arwa said. “I like the cold air.”

She adjusted her veil to cover her face, and Nuri nodded and let the curtain fall without securing it.

Arwa leaned back and forced her tense fingers to uncurl from the panel. Traveling through Chand province hadn’t been so bad, but once her retinue had reached Numriha, the journey had become almost unbearable. A frame of wood and silk was a decent enough mode of transport on even paths, such as were naturally found in the flat fields of Chand, but the palanquin was ill-suited for travel up winding mountain roads. And Numriha was all mountains. Here, the disrepair of the Empire’s trade routes was impossible to ignore.

Arwa had heard the guards complain of it often enough: the way the once grand passes through the Nainal Mountains had grown unstable from rainfall and avalanche, their surfaces by turns sheer as a knife edge or gouged with deep, ankle-twisting holes. One misplaced step, and a man could easily stumble and fall straight to his death down the mountainside.

“If the roads don’t kill us,” one guard had said to Nuri, “then the bandits are bound to do it. These Numrihans are like goats.”

“Goats,” Nuri had said, nonplussed.

“They can climb anything. I once heard of one Numrihan bastard who jumped down right into the heart of a lady’s retinue, straight into her palanquin—cut clean through the woman’s throat—”

“Don’t scare her,” another guard had said. “Besides, what if she’s listening?” She, of course, being Arwa. Their fragile, silk-swaddled package, silent inside her four walls. “She doesn’t sleep as it is. Girl,” he said to Nuri, “you tell your lady she needn’t fear these people. They’re not Ambhan, not proper, but they’re no blood-worshipping heathens either. They’ll leave us be.”

“It’s not fear of bandits or Amrithi that keeps my lady awake,” Nuri had said coolly, and that of course had been the end of that conversation.

They all knew—or thought they knew—why Arwa did not sleep.

For four days, Arwa’s nausea had ebbed and flowed along with the shuddering movement of the palanquin, as she was carried slowly up the narrow and treacherous pass. She could not see the road from her veiled seat, but her body was painfully aware of the truth of her retinue’s grumbling. Once that day already, she’d stopped to heave up her guts by the roadside, as her guardswomen milled close by and her guardsmen waited farther up the pass, respectful of her dignity. Nuri had stroked her hair and given her water to drink, and told her there was no need for shame, my lady, no need. Arwa had not agreed, and still did not, but she knew no one expected her to be strong. If anything, her weakness was a comfort to them. It was expected.

She was grieving, after all.

Arwa sank deeper into her furs, her veil a cloying weight against her skin, and tried to think of anything but the ache of her stomach, the heat of nausea prickling over her flesh. She turned her head to the faint bite of cold air creeping in through the narrow gap between the curtain and the palanquin itself, hoping its chill would soothe her. Even through the rich weight of the curtain, she could see the flicker of the lanterns carried by her guardswomen, and hear her guardsmen speak to one another in low voices, discussing the route that lay before them, made all the more treacherous by nightfall.

The male guards were meant to walk in a protective circle around her guardswomen, close enough to defend her, but far enough from her palanquin to ensure she was not directly at risk of being visible to common men. But the narrowness of the path and the dangers posed by following a cliff-edge road in darkness had made following proper protocol impossible. Instead all her guards snaked forward in an uneven, mixed-gender line, with her palanquin at its center.

She felt the palanquin jolt again, and this time she did swear. She hurriedly gripped the edge of a panel again as her retinue came to a stop, voices beyond the curtain rising and mingling in a wave of indecipherable noise. Someone’s voice rose higher, and then suddenly she could hear the crunch of booted footsteps against stone, growing louder and then fading away.

Her palanquin was lowered to the ground. The path was so uneven that it tipped slightly to one side as it touched soil—enough to make the curtain flutter, and Arwa’s weight fall naturally against one wall.

Arwa wondered, briefly, if bandits had fallen upon them after all. But she could hear no weapons and no more shouting, only silence.

Perhaps the guards had simply abandoned her. It was not unheard of. She knew very well how easily a soldier’s loyalty could falter, how much coin and wine and bread it took to keep a soldier loyal, when danger and hardship presented themselves. Steeling herself for the worst, she drew the curtain the barest sliver wider. She saw Nuri’s silhouette in the darkness, saw her carefully adjust her own shawl around her head, lantern light flickering around her, as she kneeled down to Arwa’s level.

“My lady,” Nuri said, voice painstakingly deferential. “The palanquin can go no farther. We will need to walk the final steps together. The men have gone back down the path, and will not see you, if you come out now.”

When Arwa did not respond, Nuri said gently, “It is not far, my lady. I’ve been told it’s an easy walk.”

An easy walk. Of course it was. Most of the women who took the final steps of this journey were not as young or as healthy as Arwa. She adjusted her shawl and her veil. Last of all, she touched the sash of her tunic, hidden beneath the weight of her furs and her shawl and her long brocade jacket. Within her sash, she felt the shape of her dagger, swaddled in protective leather. It lay near her skin where it rightly belonged.

She pushed back the curtain of the palanquin. Her muscles were stiff from the journey, but Nuri and one of the guardswomen were quick to help her to her feet.

As soon as Arwa was standing, with the cold night air all around her, she felt indescribably better. There was a staircase at the side of the path, carved into rock and rimmed in pale flowers, leading up to a building barely visible through the darkness.

She could have walked alone and unaided up those steps, but Nuri had already taken her arm, so Arwa allowed herself to be guided. The steps were blessedly even beneath her feet. She heard the whisper of Nuri’s footsteps, the gentle clang of the guardswomen before her and behind her, their lanterns bright moons in the dark. She raised her head, gazing up through the gauze of her veil at the night sky. The sky was a blanket scattered with stars, vast and unclouded. She saw no birds in flight. No strange, ephemeral shadows. Just the mist of her own breath, as its warmth uncoiled in the air.

Good.

“Careful, my lady,” said Nuri. “You’ll stumble.”

Arwa lowered her head and looked obediently forward. At the top of the staircase, she caught her first proper glimpse of her new home. She stopped, ignoring Nuri’s insistent hand on her arm, and took a moment to gaze at it.

The hermitage of widows was a beautiful building, built of a stone so luminescent it seemed to softly reflect back the starlight. Its three floors rested on pale columns carved to resemble trees, rootless and ethereal, arching their canopies over white verandas and latticed windows bright with lantern light. Within it, the widows of the nobility prayed and mourned, and lived in peaceful isolation.

Arwa had thought, somewhat foolishly, that it would look more like the squalid grief-houses of the common people, where widows with no husband to support them and with family lacking in the means or compassion to keep them were discarded and left to rely on charity. But of course, the nobility would never allow their women to suffer so in shame and discomfort. The hermitage was a sign of the nobility’s generosity, and of the Emperor’s merciful kindness.

Finally, she allowed Nuri to guide her forward again, and entered the hermitage. Three women, hair cut short in the style worn by widows, were waiting for her in the foyer. One sat on a chair, a cane before her. Another stood with her hands clasped at her back, and a third still stood ahead of the rest, twisting the ends of her long shawl nervously between her fingers. Behind them, leaning over balconies and standing in corridors were… all the other women in the hermitage, Arwa thought wildly. By the Emperor’s grace, had they all truly come to greet her?

She shook off Nuri’s grip and stepped forward, removing her veil as the third, nervous woman approached her. Arwa forced herself to make a gesture of welcome—forced herself not to flinch as the woman’s eyes grew teary, and she reached for Arwa’s hands.

The woman was old—they were all old to her weary eyes—and the hands that took Arwa’s own and held them firm were soft as wrinkled silk.

“My dear,” said the woman. “Lady Arwa. Welcome. I am Lady Roshana, and I must say I am very glad to see you here safe. My companions are Asima, who is seated, and Gulshera. If you need anything, you must come to us, understand?”

“Thank you,” Arwa whispered. She looked at the woman’s face. The shawl she wore over her short hair was plain, as one would expect of a widow, but it was made of a rare knot-worked silk only common in one village of Chand, and accordingly eye-wateringly expensive. She wore no jewels but a gem in her nose, a diamond of pale, minute brilliance. This woman, then, was the most senior noblewoman of the hermitage, by dint of her wealth and no doubt her lineage, and the two others were the closest to her in stature. “It’s a great honor to be here, Aunt,” Arwa said, using a term of respect for an elder woman.

“You are so young!” exclaimed Roshana, staring at Arwa’s face. “How old are you, my dear?”

“Twenty-one,” said Arwa, voice subdued.

A noise rippled through the crowd, hushed and sad. Noblewomen could not remarry; to be young and widowed was a tragedy.

Arwa’s skin itched beneath so many eyes.

“Shame, shame,” said Asima from her chair, overloud.

“I truly hadn’t expected you to be so young,” Roshana breathed, still damp-eyed. “I thought you would be—older. Why, you are near a child. When I heard the widow of the famed commander of Darez Fort was coming to us—”

Arwa flinched. She could not help it. Even the name of the place burned, still. It was just her luck that Roshana did not see it. Instead, Roshana was still staring at her damply, still chattering on.

“… have you no family, my dear, who could have taken care of you? After what you’ve been through!”

Arwa wanted to wrench her hand free of Roshana’s grip, but instead she swallowed, struggling to find words that weren’t cutting sharp, words that would not flay this fool of a woman open.

How dare you ask me about Darez Fort.

How dare you ask me about my family, as if your own have not left you here to rot.

How dare—

“I chose to come here, Aunt,” Arwa said, her voice a careful, soft thing.

She could have told the older widow that her mother had offered to take her home. She’d offered it even as she’d cut Arwa’s hair after the formal funeral, the one that took place a full month after the real bodies from Darez Fort had been buried. Maryam had cut Arwa’s hair herself, smoothing its shorn edges flat with her fingers, tender with terrible disappointment. As Arwa’s hair had fallen to the ground, Arwa had felt all Maryam’s great dreams fall with it. Dreams of renewed glory. Dreams of second chances. Dreams of their family rising from disgrace.

Arwa’s marriage should have saved them all.

You could come back to Hara, Maryam had said. Your father has asked for you. A pause. The snip of shears. Maryam’s fingers, thin and cold, on her scalp. He asked me to remind you that as long as he lives, you have a place in our home.

But Roshana had no right to that knowledge, so Arwa only added, “My family understand I wish to mourn my husband in peace.”

Roshana gave a sniffle and released Arwa’s hands. She placed her fingertips gently against Arwa’s cheek. “You must still love him very much,” she said.

I should weep, Arwa thought. They expect me to weep. But Arwa didn’t have the strength for it, so she simply lowered her eyes and drew her shawl over her face instead, as if overcome. There was a flurry of noise from the crowd. She felt Roshana’s hand on her head.

“There, there now,” said Roshana. “All is well. We will take care of you, my dear. I promise.”

“She should sleep,” Asima quavered from her seat. “We should all sleep. How late is the hour?”

It was not a subtle hint.

“Rabia,” said a voice. Arwa looked up. Gulshera was speaking, gesturing to one of the women in the crowd. “Show her where her room is.”

Rabia hurried over and took Arwa’s hand in her own, ushering her forward. Arwa had almost forgotten that Nuri was present, so she startled a little, when she heard Nuri’s soft voice whisper her name, and felt her hand at her back.

Roshana’s outpouring of emotion had both embarrassed Arwa and left her uneasy. She’d treated Arwa the way a woman might treat a daughter or a longed-for grandchild. She wondered if Roshana had either daughter or grandchild, somewhere beyond the hermitage. She wondered what sort of family would discard a woman here to gather dust. She wondered what sort of family a woman would, perhaps, come here to hide from, choosing solitude and prayer over the bonds and duties of family.

She thought of her mother’s hands running through her own shorn hair. She thought of the way her mother had wept, as Arwa hadn’t: full-throated, as if her heart had utterly broken and couldn’t be mended.

I had such hopes for you, Arwa. Her voice breaking. Such hopes. And now they’re all gone. As dead as your fool husband.

She followed Rabia through the crowd into the silence of a dark, curving corridor.

The widow Rabia was dying—nearly literally, it seemed, from the way she kept spasmodically pursing and loosening her lips—to ask Arwa questions that were no doubt completely inappropriate to put to a freshly grieving widow. Accordingly, Arwa kept dabbing her eyes and sniffling as they shuffled forward, mimicking tears. If the woman was going to ask her about her husband—or worse still, about what happened at Darez Fort—then by the Emperor’s grace, Arwa was damn well going to make her feel bad about it.

“You mustn’t think badly of them all coming to look at you,” said Rabia. “They only wanted to see you are—normal. And you are. And so young.” A pause. “You must not mourn too greatly,” Rabia continued, apparently deciding to put her questions aside for now, and provide a stream of unsolicited advice instead. “Your husband died in service to the Empire. That is glorious, don’t you think?”

“Oh yes,” Arwa said, patting furiously at her eyes. “He was a brave, brave man.” She let her voice fade to a whisper. “But I can’t speak of him yet. It’s far too painful.”

“Of course,” Rabia said hurriedly, guilt finally overcoming her. They fell into silence.

Arwa’s patience—limited, at the best of times—was sorely tested when Rabia piped up again a moment later.

“I know some people say the Empire is cursed and that—the fort, you know—that it’s proof. But I don’t think that. This is your room,” she added, pushing the door open. Nuri slipped inside, leaving Arwa to deal with Rabia alone. “I think we’re being tested.”

“You think Darez Fort was a test,” Arwa said. She spoke slowly, tasting the words. They were metal on her tongue, bitter as blood.

“Oh yes,” Rabia said eagerly. She leaned forward. “All of it is intended to test us—the unnatural madness, the sickness, the blight on Irinah’s desert. One day the Maha is going to return, if we prove our worth against evil forces, if we show we are strong and pious. And what happened to your husband, his bravery when the madness came, and your survival, it’s proof—”

“Thank you,” Arwa said, cutting in. Her voice was sharp. She couldn’t soften the edge on it and had no desire to. Instead she bared her teeth at Rabia, smiling hard enough to make her face hurt.

Rabia flinched back.

“You’ve been very kind,” added Arwa.

Rabia gave a weak smile in response and fled with a mumbled apology. Arwa didn’t think she’d be bothered by her again.

It was a nice enough room, once Rabia had been encouraged to leave it. It had its own latticed window, and a bed covered in an embroidered blanket. There was a low writing desk, already equipped with paper, and a lit oil lantern ready for Arwa’s own use. One of the guardswomen must have brought in Arwa’s luggage via a servants’ entrance, because her trunk was on the floor.

Nuri kneeled before it, quickly sorting through tunics and shawls and trousers, all in pale colors with light embellishment, suitable for Arwa’s new role as a widow. The ones that had grown dirty from use would be washed and aired to remove the musk from their long journey, then refolded and stored away again, packed with herbs to preserve their freshness.

Arwa sat on the bed and watched Nuri work.

Nuri was the perfect servant. Mild, discreet, attentive. Arwa had no idea what Nuri really thought or felt. It was no surprise, really: Nuri had been trained in her father’s household from childhood, under the keen eye of Arwa’s mother, who demanded only the best from her household staff, a clean veneer of loyal obedience, without flaw. She’d been sent by Arwa’s mother to accompany her on the journey from Chand to Numriha, as Arwa had not had a maidservant of her own any longer.

“The guards,” said Arwa, “are they camping overnight?”

“The hermitage provides accommodation not far from here,” Nuri said. “They’ll leave in the morning, I expect.”

“Does the hermitage have servants’ quarters?”

Nuri was momentarily silent. Arwa watched her smooth the creases from the tunic on her lap. “I thought I would sleep here,” Nuri said finally. “I have a bedroll. I would be able to care for you then, my lady.”

“I don’t want you to stay,” said Arwa. “Not here in my room tonight, or in the hermitage at all. You can accompany the guards back tomorrow. I’ll pay for your passage back to Hara.”

“My lady,” Nuri said quietly. “Your mother bid me to stay with you.”

“You can tell her I made you leave,” Arwa said. “Tell her I refuse to have a maidservant.” Blame my grief, Arwa thought. But Nuri would surely do that without being told. “Tell her I raged at you, that I wouldn’t be reasoned with. She’ll believe it.”

“Lady Arwa,” Nuri said. There was a thread of fear in her voice. “You… you need someone to take care of you. To protect you. Lady Maryam, she…” Voice low. “I am not to speak of it. But I know.”

Ah.

Arwa swallowed, throat dry.

“I will be safe here,” she said finally. “You’ve seen the hermitage now. You can tell her so. It’s nothing but broken roads and old women. There couldn’t be anywhere safer in the world for someone who is…” Arwa paused. She could not say it. “Someone who is—afflicted. As I am. No one will discover me here. I’ll make sure of it.”

“Lady Arwa. Your mother—Lady Maryam—she insisted—”

“I can keep my own secrets safe,” Arwa cut in tiredly, ignoring Nuri’s words. “She’ll know it was my choice. She won’t cast you out for it. I expect she’ll be glad of your help with Father anyway.”

Arwa reached into her sash and removed a purse. She held it out.

“Take it,” she said. “Enough for your journey to Hara, and more for your kindness.”

If her mother had trusted Nuri with the truth of Arwa’s nature, then Nuri had no doubt been paid handsomely to accompany Arwa. But more coin would not hurt her, and would perhaps soften her to Arwa’s will.

At first, Nuri did not move.

“Please,” said Arwa. Voice soft, now. Cajoling. “Is it so strange for me to want to be alone to mourn? To have no more eyes on me? Nuri, I am begging you—return to my mother. Allow me the dignity of a private grief.”

Hesitantly, Nuri held out her hand. Arwa placed the purse on her palm, and watched Nuri’s fingers curl over it.

“I should finish sorting your clothes,” said Nuri.

“There’s no need,” said Arwa. “You should go and rest. You have a long journey tomorrow.”

Nuri nodded and stood. “Please take care, Lady Arwa,” she said. Then she left.

Arwa kneeled and sorted through her own clothes. She would have to arrange for one of the hermitage’s servants to have them washed in the morning. When the job of sorting through her clothing was done, Arwa latched the trunk shut and closed the door.

She placed the oil lantern on the window ledge, sucked in a fortifying breath, and took her dagger from her sash.

She held the blade over the heat of the oil lantern’s flame. Her hand rested comfortably on the hilt of the blade, where the great teary opal embedded within it fitted the shape of her palm in a manner that brought her undeniable comfort. She counted the seconds, waiting for the blade to warm, and stared out the window. The dark stared back at her, velvet, oppressively lightless. She couldn’t even see the stars.

She lifted the blade up and waited for it to cool again.

She’d been too afraid to use the dagger on the journey, with Nuri always near, with her guards ever vigilant. Her dagger was far too obviously not of Ambhan design. Where the finest Ambhan daggers were richly embossed, etched with graceful birds and flowers and flecks of jewels, her own was austere and wickedly sharp, the opal in its hilt a glaring milky eye. It was an Amrithi blade, unlovely and uncivilized, and any soldier of the Empire—trained to seek and erase the presence of Amrithi barbarians, to banish them to the edges of the civilized world where they rightly belonged—would have recognized it on sight.

She recalled the guardsman’s comment on blood-worshipping heathens with bitter humor.

If only you knew, she thought, that you carried one on your shoulders all along. Oh, you would have tossed me over the cliff edge then, and you would have been proud of it.

Once in her palanquin, despite the risks, she’d made a small cut to her thumb, and daubed blood behind her ear, in the manner mothers daubed kohl behind children’s ears to keep the evil eye at bay. She’d hoped it would be enough, and perhaps it had been. She’d seen no shadows. Felt no evil descend, winged and silent. But every night she had lain awake, listening and waiting like a prey animal braced for the flash of a predator’s wings in the dark. She had imagined in great, lurid detail all the things that would happen if her meager scrape of spilled blood was not enough: Nuri’s body cut open from neck to groin, her insides splayed out around her body; the guards turning on one another, their scimitars red and silver and white as bone in the bloody dark.

Darez Fort, all over again.

And all that time, Nuri had known what Arwa was. All that time. If Arwa had only known—if she had been able to employ Nuri to distract the guards, so that she could reach her blade…

Well. No matter now. The journey was done, and soon Nuri would be gone. Useful though Nuri perhaps would have been, Arwa was grateful for that. She did not want someone to fuss over her with worried eyes. She wanted no spy from her mother, sent to ensure that she was suitably quiet and secretive and safe. The thought of Nuri remaining here made her feel suffocated.

Her mother—Emperor’s grace upon her—could not shield her. Nuri could not shield her.

Only Arwa could do that.

Once the blade had cooled, she placed its sharp edge to a finger, and watched the blood well up. The cut was shallow, the pain negligible. She placed her finger against the window ledge and drew a line across its surface.

The lantern flame flickered, caught by a faint breeze. Arwa watched it move. She thought of her husband. Of Kamran. Of a circle of blood, and a hand on her sleeve, and eyes that gleamed like gold. Her stomach felt uneasy again, roiling inside her. Her mouth was full of the taste of old iron.

Curious, how even when the heart was silent and the mind declined to recall suffering, the body still remembered.

She wiped the dagger clean on an old cloth and pressed the material to her finger finally to stem the last of the bleeding. She looked at the window. The blood was still there, illuminated by her lantern, a firm line demarcating the dark and the light, the safety of the room, and what lay beyond it.

She sat on the bed, curling up her knees. She placed the dagger by her feet, and watched the flame move. Waiting.

The night remained silent.

Nuri’s voice rose up in her. You… you need someone to take care of you. To protect you.

And who, Arwa thought, not for the first time, as sleep began to creep over her, will protect everyone from me?

If there was an answer to that question, she had not found it yet. But she would. She had to.

A noise woke her in the night, hours before dawn. She opened her eyes. Held her breath. Her heart was a pulsing fist in her chest. There was a call, hollow and cold, beyond the window. The flutter of wings.

It was just birdsong. There was nothing here. She could smell no incense in the air. See no eyes in the dark.

Feel nothing burrowing into her skull, cold-fingered and deathless.

Still, she rose to her feet. Her legs felt like water. She stared through the light of the candle. On the walls and beneath her feet the shadows flickered like beasts, unfurling with the bristle of blades and broken limbs.

It was not here. It was not here.

By the Emperor’s grace, let it not be here.

It cannot cross the blood. You’re safe, she told herself. Safe.

The air was ice around her, as she knelt on the ground, beneath the pooled light of the lantern.

“It is not here,” she whispered to herself. O

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...