- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

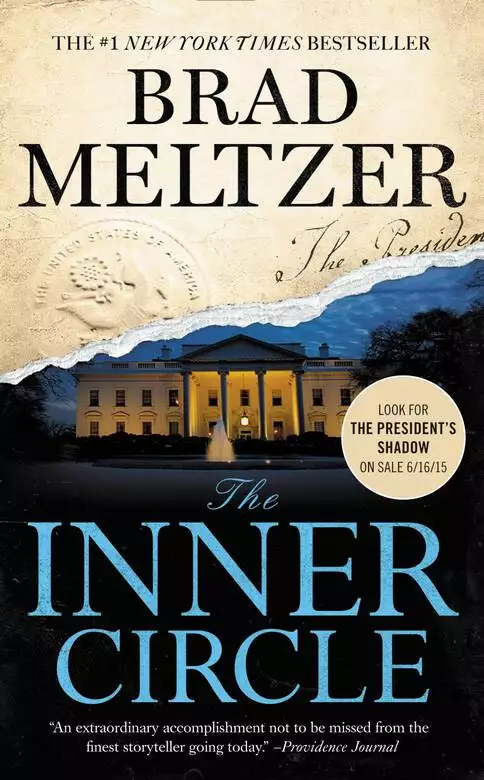

Synopsis

Beecher White, a young archivist, spends his days working with the most important documents of the US government. He has always been the keeper of other people’s stories, never a part of the story himself …

Until now.

When Clementine Kaye, Beecher’s first childhood crush, shows up at the national archives asking for his help tracking down her long lost father, Beecher tries to impress her by showing her the secret vault where the president of the United States privately reviews classified documents. After they accidentally happen upon a priceless artifact—a two-hundred-year-old dictionary that once belonged to George Washington, hidden underneath a desk chair—Beecher and Clementine find themselves suddenly entangled in a web of deception, conspiracy, and murder.

Soon a man is dead, and Beecher is on the run as he races to learn the truth behind this mysterious national treasure. His search will lead him to discover a coded and ingenious puzzle that conceals a disturbing secret from the founding of our nation. It is a secret, Beecher soon discovers, that some believe is worth killing for.

Release date: January 11, 2011

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Inner Circle

Brad Meltzer

I love those stories.

And since I work in the National Archives, I find those stories for a living. They’re almost always about other people. Not

today. Today, I’m finally in the story—a bit player in a story about…

“Clementine. Today’s the day, right?” Orlando asks through the phone from his guardpost at the sign-in desk. “Good for you,

brother. I’m proud of you.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I ask suspiciously.

“It means, Good. I’m proud,” he says. “I know what you’ve been through, Beecher. And I know how hard it is to get back in the race.”

Orlando thinks he knows me. And he does. For the past year of my life, I was engaged to be married. He knows what happened

to Iris. And what it did to my life—or what’s left of it.

“So Clementine’s your first dip back in the pool, huh?” he asks.

“She’s not a pool.”

“Ooh, she’s a hot tub?”

“Orlando. Please. Stop,” I say, lifting the phone cord so it doesn’t touch the two neat piles I allow on my desk, or the prize

of my memorabilia collection: a brass perpetual calendar where the paper scrolls inside are permanently dialed to June 19.

The calendar used to belong to Henry Kissinger. June 19 is supposedly the last day he used it, which is why I taped a note

across the base of it that says, Do Not Use/Do Not Change.

“So whattya gonna say to her?”

“You mean, besides Hello?” I ask.

“That’s it? Hello?” Orlando asks. “Hello’s what you say to your sister. I thought you wanted to impress her.”

“I don’t need to impress her.”

“Beecher, you haven’t seen this girl in what—fifteen years? You need to impress her.”

I sit on this a moment. He knows I don’t like surprises. Most archivists don’t like surprises. That’s why we work in the past.

But as history teaches me every day, the best way to avoid being surprised is to be prepared.

“Just tell me when she’s here,” I say.

“Why, so you can come up with something more mundane than Hello?”

“Will you stop with the mundane. I’m exciting. I am. I go on adventures every day.”

“No, you read about adventures every day. You put your nose in books every day. You’re like Indiana Jones, but just the professor part.”

“That doesn’t make me mundane.”

“Beecher, right now I know you’re wearing your red-and-blue Wednesday tie. And you wanna know why? Because it’s Wednesday.”

I look down at my red-and-blue tie. “Indiana Jones is still cool.”

“No, Indiana Jones was cool. But only when he was out experiencing life. You need to get outta your head and outta your comfort zone.”

“What happened to the earnest you’re-so-proud-of-me speech?”

“I am proud—but it doesn’t mean I don’t see what you’re doing with this girl, Beech. Yes, it’s a horror what happened with

Iris. And yes, I understand why it’d make you want to hide in your books. But now that you’re finally trying to heal the scab,

who do you pick? The safety-net high school girlfriend from fifteen years in your past. Does that sound like a man embracing

his future?”

I shake my head. “She wasn’t my girlfriend.”

“In your head, I bet she was,” Orlando shoots back. “The past may not hurt you, Beecher. But it won’t challenge you either,” he adds. “Oh, and do me a favor: When you run down here, don’t

try to do it in under two minutes. It’s just another adventure in your brain.”

Like I said, Orlando knows me. And he knows that when I ride the elevator, or drive to work, or even shower in the morning,

I like to time myself—to find my personal best.

“Wednesday is always Wednesday. Do Not Change.” Orlando laughs as I stare at the note on the Kissinger calendar.

“Just tell me when she’s here,” I repeat.

“Why else you think I’m calling, Dr. Jones? Guess who just checked in?”

As he hangs up the phone, my heart flattens in my chest. But what shocks me the most is, it doesn’t feel all that bad. I’m

not sure it feels good. Maybe it’s good. It’s hard to tell after Iris. But it feels like someone clawed away a thick spiderweb

from my memory, a spiderweb that I didn’t even realize had settled there.

Of course, the memory’s of her. Only she could do this to me.

Back in eighth grade, Clementine Kaye was my very first kiss. It was right after the bright red curtains opened and she won

the Battle of the Bands (she was a band of one) with Joan Jett’s “I Love Rock ’n Roll.” I was the short kid who worked the

spotlights with the coffee-breath A/V teacher. I was also the very first person Clementine saw backstage, which was when she

planted my first real wet one on me.

Think of your first kiss. And what it meant to you.

That’s Clementine to me.

Speedwalking out into the hallway, I fight to play cool. I don’t get sick—I’ve never been sick—but that feeling of flatness

has spread through my whole chest. After my two older sisters were born—and all the chaos that came with them—my mother named

me Beecher in hopes that my life would be as calm and serene as a beach. This is not that moment.

There’s an elevator waiting with its doors wide open. I make a note. According to a Harvard psychologist, the reason we think

that we always choose the slow line in the supermarket is because frustration is more emotionally charged, so the bad moments

are more memorable. That’s why we don’t remember all the times we chose the fast line and zipped right through. But I like

remembering those times. I need those times. And the moment I stop remembering those times, I need to go back to Wisconsin and leave D.C. “Remember this

elevator next time you’re on the slow line,” I whisper to myself, searching for calm. It’s a good trick.

But it doesn’t help.

“Letsgo, letsgo…” I mutter as I hold the Door Close button with all my strength. I learned that one during my first week in

the Archives: When you have a bigwig who you’re taking around, hold the Door Close button and the elevator won’t stop at any

other floors.

We’re supposed to only use it with bigwigs.

But as far as I’m concerned, in my personal universe, there’s no one bigger than this girl—this woman… she’s a woman now—who

I haven’t seen since her hippie, lounge-singer mom moved her family away in tenth grade and she forever left my life. In our

religious Wisconsin town, most people were thrilled to see them go.

I was sixteen. I was crushed.

Today, I’m thirty. And (thanks to her finding me on Facebook) Clementine is just a few seconds away from being back.

As the elevator bounces to a halt, I glance at my digital watch. Two minutes, forty-two seconds. I take Orlando’s advice and

decide to go with a compliment. I’ll tell her she looks good. No. Don’t focus on just her looks. You’re not a shallow meathead. You can do better, I decide as I take a deep breath. You really turned out good, I say to myself. That’s nicer. Softer. A true compliment. You really turned out good.

But as the elevator doors part like our old bright red curtains, as I anxiously dart into the lobby, trying with every element

of my being to look like I’m not darting at all, I search through the morning crowd of guests and researchers playing bumper

cars in their winter coats as they line up to go through the metal detector at security.

For two months now, we’ve been chatting via email, but I haven’t seen Clementine in nearly fifteen years. How do I even know

what she…?

“Nice tie,” Orlando calls from the sign-in desk. He points to the far right corner, by the lobby’s Christmas tree, which is

(Archives tradition) decorated with shredded paper. “Look.”

Standing apart from the crowd, a woman with short dyed black hair—dyed even darker than Joan Jett—raises her chin, watching

me as carefully as I watch her. Her eye makeup is thick, her skin is pale, and she’s got silver rings on her pinkies and thumbs,

making her appear far more New York than D.C. But what catches me off guard is that she looks… somehow… older than me. Like

her ginger brown eyes have seen two lifetimes. But that’s always been who she was. She may’ve been my first kiss, but I know

I wasn’t hers. She was the girl who dated the guys two grades above us. More experienced. More advanced.

The exact opposite of Iris.

“Clemmi…” I mouth, not saying a word.

“Benjy…” she mouths back, her cheeks rising in a smile as she uses the nickname my mom used to call me.

Synapses fire in my brain and I’m right back in church, when I first found out that Clementine had never met her dad (her

mom was nineteen and never said who the boy was). My dad died when I was three years old.

Back then, when combined with the kiss, I thought that made Clementine Kaye my destiny—especially for the three-week period

when she was home with mono and I was the one picked to bring her assignments home for her. I was going to be in her room—near

her guitar and her bra (Me. Puberty.)—and the excitement was so overwhelming, as I knocked on her front door, right there,

my nose began to bleed.

Really.

Clementine saw the whole thing—even helped me get the tissues that I rolled into the nerd plugs that I stuffed in my nostrils.

I was the short kid. Easy pickings. But she never made fun—never laughed—never told the story of my nosebleed to anyone.

Today, I don’t believe in destiny. But I do believe in history. That’s what Orlando will never understand. There’s nothing

more powerful than history, which is the one thing I have with this woman.

“Lookatyou,” she hums in a soulful but lilting voice that sounds like she’s singing even when she’s just talking. It’s the

same voice I remember from high school—just scratchier and more worn. For the past few years, she’s been working at a small

jazz radio station out in Virginia. I can see why. In just her opening note, a familiar tingly exhilaration crawls below my

skin. A feeling like anything’s possible.

A crush.

For the past year, I’d forgotten what it felt like.

“Beecher, you’re so… You’re handsome!”

My heart reinflates, nearly bursting a hole in my chest. Did she just—?

“You are, Beecher! You turned out great!”

My line. That’s my line, I tell myself, already searching for a new one. Pick something good. Something kind. And genuine. This is your chance. Give her something so perfect, she’ll dream about it.

“So… er… Clemmi,” I finally say, rolling back and forth from my big toes to my heels as I notice her nose piercing, a sparkling

silver stud that winks right at me. “Wanna go see the Declaration of Independence?”

Kill me now.

She lowers her head, and I wait for her to laugh.

“I wish I could, but—” She reaches into her purse and pulls out a folded-up sheet of paper. Around her wrist, two vintage

wooden bracelets click-clack together. I almost forgot. The real reason she came here.

“You sure you’re okay doing this?” Clementine asks.

“Will you stop already,” I tell her. “Mysteries are my specialty.”

* * *

Seventeen years ago

Sagamore, Wisconsin

Everyone knows when there’s a fight in the schoolyard.

No one has to say a word—it’s telepathic. From ancient to modern times, the human animal knows how to find fighting. And seventh

graders know how to find it faster than anyone.

That’s how it was on this day, after lunch, with everyone humming from their Hawaiian Punch and Oreo cookies, when Vincent

Paglinni stole Josh Wert’s basketball.

In truth, the ball didn’t belong to Josh Wert—it belonged to the school—but that wasn’t why Paglinni took it.

When it came to the tribes of seventh grade, Paglinni came from a warrior tribe that was used to taking what wasn’t theirs.

Josh Wert came from a chubby tribe and was born different than most, with a genius IQ and the kind of parents who told him

never to hide it. Plus, he had a last name like Wert, which appeared in just that order—W-E-R-T—on the keyboard of every computer.

“Give it back!” Josh Wert insisted, not using his big brain and making the mistake of calling attention to what had happened.

Paglinni ignored the demand, refusing to even face him.

“I-I want my ball back!” Josh Wert added, sucking in his gut and trying so hard to stand strong.

By now, the tribe of seventh graders was starting to gather. They knew what was about to happen.

Beecher was one of those people. Like Wert, Beecher was also born with brains. At three, Beecher used to read the newspaper. Not just the comics or the sports scores. The whole newspaper, including the obituaries, which his mom let him read when his dad died. Beecher was barely four.

As he grew older, the obits became Beecher’s favorite part of the newspaper, the very first thing he read every morning. Beecher

was fascinated by the past, by lives that mattered so much to so many, but that—like his father—he’d never see. At home, Beecher’s

mom, who spent days managing the bakery in the supermarket, and afternoons driving the school bus for the high school, knew

that made her son different. And special. But unlike Josh Wert, Beecher knew how to use those brains to steer clear of most

schoolyard controversies.

“You want your basketball?” Paglinni asked as he finally turned to face Wert. He held the ball out in his open palm. “Why

don’t you come get it?”

This was the moment the tribe was waiting for: when chubby Josh Wert would find out exactly what kind of man he’d grow up

to be.

Of course, Wert hesitated.

“Do you want the ball or not, fatface?”

Seventeen years from now, when Beecher was helping people at the National Archives, he’d still remember the fear on Josh Wert’s

round face—and the sweat that started to puddle in the chubby ledges that formed the tops of Wert’s cheeks. Behind him, every

person in the schoolyard—Andrew Goldberg with his freckled face, Randi Boxer with her perfect braids, Lee Rosenberg who always

wore Lee jeans—they were all frozen in place, waiting.

No. That wasn’t true.

There was one person moving through the crowd—a late arrival—slowly making her way to the front of the action and holding

a jump rope that dangled down, scraping against the concrete.

Beecher knew who she was. The girl with the long black hair, and the three earrings, and the cool hipster black vest. In this

part of Wisconsin, no one wore cool hipster vests. Except the new girl.

Clementine.

In truth, she really wasn’t the new girl—Clementine had been born in Sagamore, and lived there until about a decade ago, when her mom moved them to Detroit to

pursue her singing career. It was hard moving away. It was even harder moving home. But there was nothing more humbling than

two weeks ago, when the pastor in their church announced that everyone needed to give a big welcome back to Clementine and her mom—especially since there was no dad in their house. The pastor was just trying to be helpful. But

in that moment, he reminded everyone that Clementine was that girl: the one with no father.

Beecher didn’t see that at all. To Beecher, she was the one just like him.

Maybe that’s why Beecher did what he was about to do.

Maybe he saw something he recognized.

Or maybe he saw something that was completely different.

“Do you want the ball back or not?” Paglinni added as a thin smirk spread across his cheeks.

In the impromptu circle that had now formed around the fight, every seventh grader tensed—some excited, some scared—but none

of them moving as they waited for blood.

Clementine was the opposite—fidgety and unable to stand still while picking at the strands of the jump rope she was still

clutching. As she shifted her weight from one foot to the other, Beecher felt the energy radiating off her. This girl was

different from the rest. She wasn’t scared like everyone else.

She was pissed. And she was right. This wasn’t fair…

“Give him his ball back!” a new voice shouted.

The crowd turned at once—and even Beecher seemed surprised to find that he was the one who said it.

“What’d you say, Beech Ball!?” Paglinni challenged.

“I-I said… give him the ball back,” Beecher said, amazed at how quickly adrenaline could create confidence. His heart pumped

fast. His chest felt huge. He stole a quick glance at Clementine.

She shook her head, unimpressed. She knew how stupid this was.

“Or what…?” Paglinni asked, the basketball cocked on his hip. “What’re you gonna possibly do?”

Beecher was in seventh grade. He didn’t have an answer. But that didn’t stop him from talking. “If you don’t give Josh the

ball back—”

Beecher didn’t even see Paglinni’s fist as he buried it in Beecher’s eye. But he felt it, knocking him off his feet and onto

his ass.

Like a panther, Paglinni was all over him, pouncing on Beecher’s chest, pinning his arms back with his knees, and pounding

down on his face.

Beecher looked to his right and saw the red plastic handle of the jump rope, sagging on the ground. A burst of white stars

exploded in his eye. Then another. He’d never been punched before. It hurt more than he thought.

Within seconds, the tribe was screaming, roaring—Pag! Pag! Pag! Pag!—chanting along with the impact of each punch. There was a pop from Beecher’s nose. The white stars in Beecher’s eyes suddenly

went black. He was about to pass out—

“Huuuhhh!”

Paglinni fell backward. All the weight came off Beecher’s chest. Beecher could hear the basketball bouncing across the pavement.

Fresh air reentered his lungs. But as Beecher struggled to sit up and catch his breath… as he fought to blink the world back

into place… the first thing he spotted was…

Her.

Clementine pulled tight on the jump rope, which was wrapped around Paglinni’s neck. She wasn’t choking him, but she was tugging—hard—using

the rope to yank Paglinni backward, off Beecher’s chest.

“—kill you! I’ll kill you!” Paglinni roared, fighting wildly to reach back and grab her.

“You tool—you think I still jump rope in seventh grade?” she challenged, tugging Paglinni back with an eerie calm and reminding

Beecher that this wasn’t just some impromptu act. It wasn’t coincidence that Clementine had the jump rope. When she came here, she was prepared. She knew exactly what she was doing.

Still lying on his back, Beecher watched as Clementine let go of the rope. Paglinni was coughing now, down on his rear, but

fighting to get up, his fist cocked back and ready to unleash.

Yet as Paglinni jumped to his feet, he could feel the crowd turn. Punching Beecher was one thing. Punching a girl was another.

Even someone as dumb as Paglinni wasn’t that dumb.

“You’re a damn psycho, y’know that?” Paglinni growled at Clementine.

“Better than being a penis-less bully,” she shot back, getting a few cheap laughs from the crowd—especially from Josh Wert,

who was now holding tight to the basketball.

Enraged, Paglinni stormed off, bursting through the spectators, who parted fast to let him leave. And that was the very first

moment that Clementine looked back to check on Beecher.

His nose was bloody. His eyes were already starting to swell. And from the taste of the blood, he knew that his lip was split.

Still, he couldn’t help but smile.

“I’m Beecher,” he said, extending a handshake upward.

Standing above him, Clementine looked down and shook her head. “No. You’re a moron,” she said, clearly pissed.

But as the crowd dissipated and Clementine strode across the schoolyard, Beecher sat up and could swear that as he was watching

Clementine walk away in the distance… as she glanced over her shoulder and took a final look at him… there was a small smile

on her face.

He saw it.

Definitely a smile.

Today

Washington, D.C.

Thirty-two minutes later, as Clementine and I are waiting for the arrival of the documents she came looking for, I swipe my

security card and hear the usual thunk. Shoving the bank vault of a door open, I make a sharp left into the cold and poorly lit stacks that fill the heart of the

Archives. With each row of old files and logbooks we pass, a motion sensor light goes off, shining a small spotlight, one

after the other, like synchronized divers in an old Esther Williams movie, that chases us wherever we go.

These days, I’m no longer the short kid. I’m blond, tall (though Clementine still may be a hair taller than me), and dressed

in the blue lab coat that all of us archivists wear to protect us from the rotted leather that rubs off our oldest books when

we touch them. I’ve also got far more to offer her than a nosebleed. But just to be near this woman who consumed my seventh

through tenth grades… who I used to fantasize about getting my braces locked together with…

“Sorry to do this now. I hope you’re not bored,” I tell her.

“Why would I be bored? Who doesn’t love a dungeon?” she says as we head deeper into the labyrinth of leather books and archival

boxes. She’s nearly in front of me, even though she’s got no idea where she’s going. Just like in junior high. Always prepared

and completely fearless. “Besides, it’s nice to see you, Beecher.”

“Here… it’s… here,” I say as the light blinks on above us and I stop at a bookcase of rotted leather-bound logbooks that are packed haphazardly across the shelf. Some are spine out, others are stacked on top of each other. “It’s just that we have a quota

of people we have to help and—”

“Stop apologizing,” Clementine offers. “I’m the one who barged in.”

She says something else, but as I pull out the first few volumes and scan their gold-stamped spines, I’m quickly lost in the

real treasure of this trip: the ancient browning pages of the volume marked November 1779. Carefully cradling the logbook with one hand, I use my free one to pull out the hidden metal insta-shelf that’s built into

each bookcase and creaks straight at us at chest height.

“So these are from the Revolutionary War?” she asks. “They’re real?”

“All we have is real.”

By we, I mean here—the National Archives, which serves as the storehouse for the most important documents of the U.S. government, from the original

Declaration of Independence, to the Zapruder film, to reports on opportunities to capture bin Laden, to the anthrax formula

and where the government stores the lethal spores, to the best clandestine files from the CIA, FBI, NSA, and every other acronym.

As they told me when I first started as an archivist three years ago, the Archives is our nation’s attic. A ten-billion-document

scrapbook with nearly every vital file, record, and report that the government produces.

No question, that means this is a building full of secrets. Some big, some small. But every single day, I get to unearth another

one.

Like right now.

“Howard… Howard… Howard,” I whisper to myself, flipping one of the mottled brown pages and running my pointer finger down

the alphabetical logbook, barely touching it.

Thirty-four minutes ago, as we put in the request for Clementine’s documents, a puffy middle-aged woman wearing a paisley

silk scarf as a cancer wig came into our research entrance looking for details about one of her relatives. She had his name.

She had the fact he served in the Revolutionary War.

And she had me.

As an archivist, whether the question comes from a researcher, from a regular person, or from the White House itself, it’s

our job to find the answers that—

“Beecher,” Clementine calls out. “Are you listening?”

“Wha?”

“Just now. I asked you three times and—” She stops herself, cocking her head so the piercing in her nose tips downward. But

her smile—that same warm smile from seventh grade—is still perfectly in place. “You really get lost in this stuff, don’t you?”

“That woman upstairs… I can’t just ignore her.”

Clementine stops, watching me carefully. “You really turned out to be one of the nice ones, didn’t you, Beecher?”

I glance down at the logbook. My eyes spot—

“He was a musician,” I blurt. I point to the thick rotted page, then yank a notepad from my lab coat and copy the information.

“That’s why he wasn’t listed in the regular service records. Or even the pension records upstairs. A musician. George Howard

was a musician during the Revolution.”

“Y’mean he played ‘Taps’?”

“No…‘Taps’ wasn’t invented until the Civil War. This guy played fife and drum, keeping the rhythm while the soldiers marched.

And this entry shows the military pay he got for his service.”

“That’s… I don’t even know if it’s interesting—but how’d you even know to come down here? I mean, these books look like they

haven’t been opened in centuries.”

“They haven’t. But when I was here last month searching through some leftover ONI spy documents, I saw that we had these old

accounting ledgers from the Treasury Department. And no matter what else the government may screw up, when they write a check

and give money out, you better believe they keep pristine records.”

I stand up straight, proud of the archeological find. But before I can celebrate—

“I need some ID,” a calm voice calls out behind us, drawing out each syllable so it sounds like Eye. Dee.

We both turn to find a muscular, squat man coming around the far corner of the row. A light pops on above him as he heads

our way. Outfitted in full black body armor and gripping a polished matching black rifle, he studies my ID, then looks at

the red Visitor badge clipped to Clementine’s shirt.

“Thanks,” he calls out with a nod.

I almost forgot what day it was. When the President comes, so does the…

“Secret Service,” Clementine whispers. She cocks a thin, excited eyebrow, tossing me the kind of devilish grin that makes

me feel exactly how long I haven’t felt this way.

But the truly sad part is just how wonderful the rush of insecurity feels—like rediscovering an old muscle you hadn’t used

since childhood. I’ve been emailing back and forth with Clementine for over two months now. But it’s amazing how seeing your

very first kiss can make you feel fourteen years old again. And what’s more amazing is that until she showed up, I didn’t

even know I missed it.

When most people see an armed Secret Service agent, they pause a moment. Clementine picks up speed, heading to the end of

the row and peeking around the corner to see where he’s going. Forever fearless.

“So these guys protect the documents?” she asks as I catch up to her, leading her out of the stacks.

“Nah, they don’t care about documents. They’re just scouting in advance for him.”

This is Washington, D.C. There’s only one him.

The President of the United States.

“Wait… Wallace is here?” Clementine asks. “Can I meet him?”

“Oh for sure,” I say, laughing. “We’re like BFFs and textbuddies and… he totally cares about what one of his dozens of archivists

thinks. In fact, I think his Valentine’s card list goes: his wife, his kids, his chief of staff… then me.”

She doesn’t laugh, doesn’t smile—she just stares at me with deep confidence in her ginger brown eyes. “I think one day, he

will care about you,” she says.

I freeze, feeling a blush spread across my face.

Across from me, Clementine pulls up the sleeve of her black sweater, and I notice a splotch of light scars across the outside

of her elbow. They’re not red or new—they’re pale and whiter than her skin, which means they’ve been there a lon

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...