- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

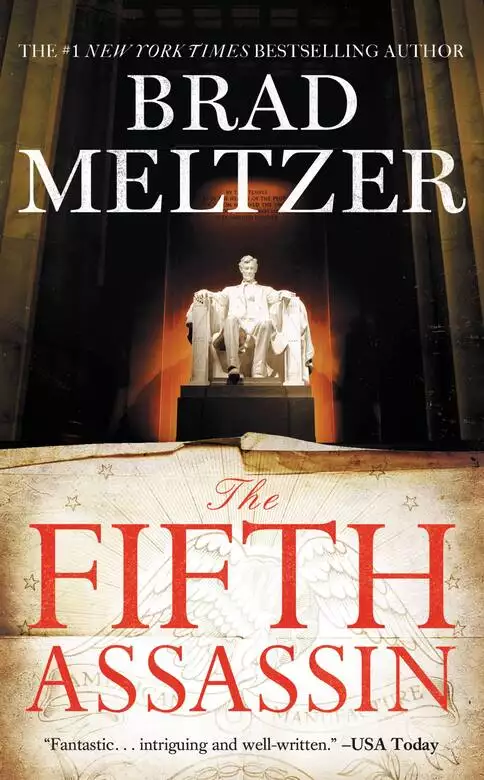

From John Wilkes Booth to Lee Harvey Oswald, there have been twenty-four assassination attempts on the President of the United States. Four have been successful. But now, Beecher White—the hero of the #1 bestseller The Inner Circle—discovers a killer in Washington, DC, who’s meticulously re-creating the crimes of the world’s most famous assassins: John Wilkes Booth, Charles Guiteau, Leon Czolgosz, and Lee Harvey Oswald. But scariest of all is what all four assassins have in common. Historians have branded them as four lone wolves. But what if they were wrong? Beecher is about to find out the truth: that over the course of a hundred years, all four assassins were secretly working together. What was their purpose? Who do they really work for? And why are they planning to killing the President today? Beecher’s about to find out. And most terrifying, he’s about to come face-to-face with the fifth assassin.

Release date: January 15, 2013

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Fifth Assassin

Brad Meltzer

Washington, D.C.

The Knight knew his history. And his destiny. In fact, no one studied those more carefully than the Knight.

Rolling a butterscotch candy around his tongue, he pulled the trigger at exactly 10:11 p.m.

The gun—an antique pistol—let out a puff of blue-gray smoke, sending a spray of meat and blood across the wooden pews of St. John’s Church, the historic building that sat directly across the street from the White House.

“Y-You shot me…” the rector cried, clutching the back of his shoulder—his collarbone felt shattered—as he reeled sideways and stumbled down the main aisle.

The blood wouldn’t stop. But the Knight’s gun hadn’t delivered a killshot. At the last minute, the rector, who’d been in charge of St. John’s for nearly a decade, had moved.

The Knight just stood there, waiting for him to fall. The stark white plaster mask he wore ensured that his victim couldn’t get a good look at his face. But the rector still had his strength.

Sliding his gun back in his pocket, the Knight moved calmly, almost serenely down the aisle, toward the ornate altar.

“Help! Someone… please! Someone help me!” the rector, a sixty-year-old man with rosy cheeks, gasped as he ran, looking back at the frozen white mask, like a death mask, that followed him.

There was a reason the Knight had picked a church, especially this church, dubbed “the Church of the Presidents” because every President since James Madison had worshiped here.

It was the same with the homemade tattoo on the web of skin between his own thumb and pointer-finger. The Knight had finished the tattoo last night, using white ink since it was invisible to the naked eye. It took five needles, which he bundled together and dipped in ink, and four hours in total, puncturing his skin over and over, wiping away the blood.

The only break he took was right after he had finished the first part—the initials. Then, from his pocket, he had pulled out a yellowed deck of playing cards, thumbing past the hearts, clubs, and diamonds, stopping on… Spades.

In the dictionary, spades were defined as shovels. But when the four suits of cards were introduced centuries ago, each one had its own cryptic meaning. The spade wasn’t a tool to dig with. It was the point of a lance.

The weapon of a knight.

“I need help! Please… anyone!” the rector screamed, scrambling frantically and making a sharp right through the double doors and down the long hallway that led out of the sanctuary.

The Knight’s pace was perfectly steady as he followed the curved hallway back toward the church offices. His breath puffed evenly against the white plaster mask.

Up ahead, from around the corner, he heard a faint beep-beep-boop of a cell phone. The rector was trying to call 911.

But like his hero, who had done this so long ago, the Knight left nothing to chance. The plastic gray device in his pocket was the size of a cell phone, and could kill any cell signal in a fifty-yard radius. Cell jammers were illegal in the United States. But they cost less than $200 on a UK website.

Around the corner, where the main church offices began, there was a dull thud of a shoulder hitting wood: the rector realizing that the doorknob had been removed from the front door. Then the loud thunderclap of an office door slamming shut. The rector was hiding now, in one of the offices.

In the distance, the faint sound of police sirens was getting louder. No way was the rector able to call 911, but even if he was, the maze had nothing but dead ends left.

Looking right, then left, the Knight checked the antique parlor rooms that the church now used for AA meetings and for the “Date Night” services they held for local singles. This side of the building, known as the Parish House, was nearly as old as the church itself, but not nearly as well kept up. Throughout the main floor, every one of the tall cherry office doors was open. Except one.

With a sharp twist of the oval brass doorknob, the Knight shoved the large door open. The sirens were definitely getting louder. In the far left corner, by the bookcase, the rector was crying, still trying to pry open the room’s only window, which the Knight had nailed shut hours earlier.

Moving closer, the Knight glided past a glass case, never glancing at its beautiful collection of fifty antique crosses mounted on red velvet.

“You can’t do this! God will never forgive you!” the rector pleaded.

The Knight stepped toward him, taking hold of the rector’s shattered shoulder. Under the mask, he rolled a butterscotch candy around his tongue. From his belt, he pulled out a knife.

One side of his blade had the words “Land of the Free/Home of the Brave,” etched in acid, while the other side was etched with “Liberty/Independence.” Just like the one his hero had over a century ago.

Taking a final breath that gave him a sense of weightlessness, he clenched his butterscotch candy in the vise of his back teeth.

“W-Why’re you doing this?” the rector pleaded as the sirens grew deafening.

“Isn’t it obvious?” The Knight raised his knife and plunged it straight into the rector’s throat. The butterscotch candy cracked in half. “I’m getting ready for the President of the United States.”

There are stories no one knows. Hidden stories.

I love those stories. And since I work in the National Archives, I find those stories for a living. But at 7:30 in the morning, as the elevator doors slide open and I scan the quiet fourth-floor hallway, I’m starting to realize that some of those stories are even more hidden than I thought.

“Nothing?” Tot asks, waiting for me outside our office. The way he’s rolling his finger into his overgrown beard, he knows the answer.

“Less than nothing,” I confirm, holding a file folder in my gloved open palms and double-checking to make sure we’re alone.

Aristotle “Tot” Westman is my mentor here at the Archives, and the one who taught me that the best archivists are the ones who never stop searching. At seventy-two years old, he’s had plenty of practice.

He’s also the one who invited me into the Culper Ring.

The Ring was started by George Washington.

I know. I had the same reaction. But yes, that George Washington.

Two hundred years ago, back during the Revolutionary War, Washington built his own private spy ring. Not only did it help him win the war, but it helped protect the Presidency. The Ring still exists today, and now I’m a part of it.

“Beecher, you knew he wasn’t gonna make it easy.”

“I’m not asking for easy; I’m looking for possible. It’s like there’s nothing to find.”

“There’s always something to find. I promise.”

“Yeah, you’ve been making that promise for two months now,” I say, referring to how long it’s been since Tot and I started coming in at 7 a.m.—before any of the other archivists show up—privately digging through every presidential file we can find.

“What’d you expect? That you can look under P and find everything you need for Evil President?” Tot challenges.

“Actually, Evil President would be filed under E.”

“Not if it’s his first name. Though it does depend on the record group,” Tot clarifies, hoping the bad joke will lighten the mood. It doesn’t. “The point is, Beecher, we know the hard part: We know what Wallace and Palmiotti did; we know how they did it; and when they were done with their baseball bat and razor-sharp car keys, we even know they put a young man into a permanent coma and left him to die. Now all we have to do is prove it. I’m thinking we should start picking up the pace.”

As Tot says the words, he runs his fingertips down the metal strands of his bolo tie, which he doesn’t realize is as socially extinct as the Scottsdale boutique where he bought it back in 1994. The thing is, I know Tot. And I know that tone.

“Why’d you just say we need to pick up the pace?” I ask.

At first, Tot stays quiet, rechecking the hallway.

“Tot, if you know something…”

“One of our guys,” he begins, using that phrase he saves for when he’s talking about other members of the Culper Ring. “One of them spoke to someone in the Secret Service, asking what they knew about you. And y’know what the guy in the Service said? Nothing. Not a sound. You know what that means, Beecher?”

“It means they’re worried about me.”

“No. It means the President already knows how this ends. All he’s doing now is working on his cover story.”

Letting the words sink in, Tot again rechecks the hallway. I tell myself the proof is still in the Archives… somewhere… in some file. It’s no small haystack.

The National Archives is the storehouse for the most important items in the U.S. government, from the original Declaration of Independence to Jackie Kennedy’s bloody pink dress… from Reagan’s original “Evil Empire” speech to the tracking maps we used to catch and kill bin Laden. Over ten billion pages strong, we house and catalog every vital file, record, and report that’s produced by the government.

As I always say, that means we’re a building full of secrets—especially for sitting Presidents, since we store everything from their grade school report cards, to their yearbooks, to, the theory goes, old forgotten medical records that might prove what President Wallace really did that night twenty-six years ago.

“Have you thought about ordering his marathon files?” Tot asks.

“Already did. That’s what came this morning.”

For two months now, we’ve sifted through every puzzle piece of President Wallace’s medical history, from back in college when he was in ROTC, to the physical exam he took when his daughter was born and he bought his first insurance policy, to the X-rays that were taken back when he was just a governor and he ran the Marine Marathon despite having a hairline fracture in his foot. That fracture brought Wallace national attention as a politician who never quits. We were hoping it’d bring us something even better. Yet like every medical document related to the President, everything comes back empty, empty, empty.

“He can’t hide it all, Beecher.”

“Tell that to FDR’s medical records,” I reply. Tot doesn’t argue. Back in 1945, forty-eight hours after Franklin Delano Roosevelt died, his medical records were stolen and destroyed. No one’s found them since.

“So if Wallace’s marathon X-rays were a bust, what’s that?” Tot asks, pointing to the file folder that I’m still holding in my open palm.

“Just something I pulled from our Civil War records. A letter from Abraham Lincoln’s son talking about his years in the White House.” Tot knows that when I’m nervous, I like to read old history. But he also knows that nothing makes me more nervous than the most complex history of all: family history.

“Your mom called while you were down there, didn’t she?” Tot asks.

I nod. After my mom’s heart surgery, I asked her to call me every morning to let me know she was okay. My father died when I was three. Mom is all I’ve got left. But as always, it wasn’t my mom who called. It was my sister Sharon, who lives with and takes care of her. Every two weeks, I send part of my check home, but it’s Sharon who does the real work.

“Mom okay?” Tot asks.

“Same as always.”

“Then it’s time to focus on the problem you can actually deal with,” Tot says, motioning toward the main door to our office and reminding me that whatever President Wallace is planning, that’s where the real damage will be done. But as we step inside and I spot two men in suits standing outside my cubicle, I’m starting to think that the President’s even further along than we thought.

“Beecher White?” the taller of the two asks, though the way his dark eyes lock on me, he has the answer. He’s got a narrow face; his partner has a wide one that he tries to offset with a neatly trimmed goatee. Neither looks happy. Or friendly.

“That’s me; I’m Beecher. And you are…?” I ask, though neither of them answers. As Tot limps and ducks into his own cubicle, I see that both my visitors are wearing gold lapel pins with a familiar five-pointed star. Secret Service.

I glance over at Tot, who smells the same rat I do.

“You mind answering a few questions?” the agent with the narrow face asks as he flashes his badge, which says Edward Harris. Before I can answer, he adds, “You always at work this early, Mr. White?”

I have no idea where the bear trap is, but I already feel its springs tightening. Last time I saw President Wallace, I told him I’d do everything in my power to find the evidence to prove what he and his dead friend Palmiotti did. In return, the most powerful man in the world leaned forward on his big mahogany desk in the West Wing and told me, as if it were an absolute fact, that he would personally erase me from existence. So when two Secret Service agents are asking me questions before eight in the morning, I know that whatever they want, I’m in for some pain.

“I like getting in at seven,” I tell the agent, though from the look on his face it isn’t news to him. I make a quick mental note of every staffer and guard downstairs who saw me hunting through presidential records and might’ve tipped them off. “I didn’t realize coming to work early was a problem.”

“No problem,” Agent Harris says evenly. “And what time do you usually get home? Specifically, what time did you get home last night?”

“Just past eight,” I say. “If you don’t believe me, ask Tot. He drove me home and dropped me off.” Still standing by the door with the priceless Robert Todd Lincoln letter in my hands, I motion to Tot’s cubicle.

“I appreciate that. Tot dropped you off. That means he doesn’t know where you were between eight last night and about six this morning, correct?” the agent with the goatee asks, though it no longer sounds like a question.

It’s the first time I notice that neither of these guys has the hand mics or ear buds that you see on the Secret Service agents around the President. These two don’t do protection. They’re investigators. Still, the Service’s mission is to protect the President. In the Culper Ring, we protect the Presidency. It’s not a small distinction.

“Were you with anyone else last night, Beecher?” Agent Harris jumps in.

From his cubicle, Tot shoots me a look. The bear trap is about to snap shut.

“Do you always wear gloves at work?” Agent Harris adds, motioning to the white cotton gloves.

“Only when I’m handling old documents,” I say as I open the file folder and show them the mottled brown Robert Todd Lincoln letter that’s still in my open palms. “If you don’t mind…”

They step away from my cubicle, but not by much.

As I squeeze inside and carefully place the Lincoln letter on my desk, I notice the odd slant of my keyboard and how one of my piles of paper is slightly askew. They’ve already gone through my stuff.

“And do you take those gloves home with you?” Agent Harris asks.

“I’m sorry,” I say, “but are you accusing me of something?”

They exchange glances.

“Beecher, do you know someone named Ozzie Andrews?” Agent Harris finally asks.

“Who?”

“Just tell me if you know him. Ozzie Andrews.”

“With a name as silly as Ozzie, I’d remember if I knew him.”

“So you never met him? Never heard the name?”

“What’re you really asking?”

“They found a body,” Agent Harris says. “A pastor in a church downtown was found murdered last night around 10 p.m. Throat slit.”

“That’s horrible.”

“It is. Fortunately for us, just as the D.C. Police got there, they nabbed a suspect. Named Ozzie. He was strolling out the back of the church right after the murder. And when they went through Ozzie’s pockets, this killer had your name and phone number in his wallet.”

“What? That’s ridiculous.”

“So you don’t know anything about this murder?”

“Of course not!”

There’s a long pause.

“Beecher, how would you describe your opinion of President Orson Wallace?” Agent Harris interrupts.

“Excuse me?”

“We’re not asking your political views. It’s just, with St. John’s Church being so close to the White House… you understand. We need to ask.”

I turn to Tot, who doesn’t just smell the rat anymore; now we see it. Two months ago, as the President buried his best friend, he swore he’d also bury me. I thought it’d come in the middle of the night with a ski mask. But I forgot who I’m dealing with. Tot said the President already had the bull’s-eye on my forehead, then suddenly two Secret Service guys show up? This is Wallace’s real revenge: Tie me to a murder, send in the Service, and keep your manicured hands clean as they snap my mugshot.

“Where is this Ozzie guy now?” I ask. “I’d like to know who he is.”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t realize suspects get to make their own demands.”

“So now I’m a suspect? Fine, then let me face my accuser. Is he still in jail?”

For the first time, both agents go silent.

“What, you let him go?” I ask.

Again, silence.

“So you found the murder suspect and already let him walk? And now you think you can come here and pin it on me? Sorry, but unless you’re here to arrest me, we’re done.”

“Can you just answer one last—?”

“Done. Goodbye,” I say, pointing them to the door. For thirty seconds, they stand there, just to make it clear that it’s their choice to leave, not mine.

As the door slams behind them, I hear Tot whispering behind me.

“You’re the best, Mac. I appreciate it,” he says from his cubicle.

It’s the first time I realize Tot’s been on the phone the entire time, and when I hear the name Mac, I realize how much danger I’m really in.

When George Washington first created the Culper Ring, he picked regular, ordinary people because no one looks twice at them. His only other rule was this: that even he should never know the names of all the members. That way, if one of them got caught passing information, the enemy would never be able to track the others.

That’s the real reason why the Culper Ring has been able to exist to this very day—and why they’ve had a hand in everything from the Revolutionary War, to Hiroshima, to the Bay of Pigs. Before the OSS, or the CIA, these guys wrote the book on keeping secrets. So when it comes to other Culper members, there’s only one besides Tot that I’ve met face-to-face. He’s a doctor; they call him The Surgeon. That’s it, no name. He took four pints of my blood in case of emergency. But there’s one other member I’ve been warned about.

Tot calls him Mac—which is short for The Immaculate Deception—which is short for when it comes to hacking, if we need something, Mac’s the one who’ll get it. The only thing he asks in return is that we buy Girl Scout cookies from his niece.

“You owe me another box of Samoas,” Mac says through Tot’s cell.

“Y’mean Caramel deLites,” Tot says.

“I don’t care if they changed the name. They’re Samoas to me,” Mac says in the text-to-speech voice generator that draws out every syllable in the word sa-mo-as and makes him sound like a 1960s robot.

No one’s ever heard his real voice.

From what Tot says, Mac was one of the Seven. In case of a national emergency, if the Internet and our computer infrastructure go down, seven people in the U.S. government have the capability to put it back up again. Five of the seven need to be present to do it. Mac, before he left the government behind, used to be one of them.

Cool story, right? It’s not the only one. According to the Surgeon, Mac isn’t a retired tech genius. He’s a nineteen-year-old social misfit who, like every talented hacker who gets caught by the U.S. government, is hired to work for the U.S. government. The Girl Scout cookies are really for his sister.

I don’t care which story is true. All I care is that when trouble hits, no one’s faster than the Immaculate Deception.

Tot hands me his phone over the cubicle partition. Onscreen is a photo of a man with buzzed black hair, standing against a light gray wall. My accuser Ozzie’s mugshot. He looks about my age, but it’s hard to tell since his face… his right eye sags slightly, making him look permanently sleepy—and the way his face is lumpy, like it’s coated with a shiny putty… I think he’s a burn victim.

Then I notice his eyes. They’re pale gold like the color of white wine.

Behind me, the door to our office opens as one of our fellow employees arrives. I barely hear it. My skin goes so cold, it feels like it’s about to crack off my body.

There’s only one person I know with gold eyes. And as I study the photo, as I look past the burns… No. It’s impossible. It can’t be him.

But I know it is.

Marshall.

Twenty years ago

Sagamore, Wisconsin

Marshall didn’t hear the rip.

Like any fifth-grade boy, he was moving too fast as he kicked open the passenger door. Even in the small and usually slow town of Sagamore, even before his dad put the car in park, Marshall was out in the cold, racing around to the back of the car and using all his strength to pull his dad’s wheelchair from the trunk.

Barely ten years old, the youngest in his grade, Marshall was always told he was chubby, not fat—that his weight was perfect, but his height just needed to catch up. He believed it too, anxiously awaiting the day that God would even things out and make him more like his fellow fifth graders: tall like Vincent or skinny like Beecher.

Marshall was a polite kid—almost to a fault—with a mom so strict she taught him that if he had to pass gas, he had to leave the room. Discipline ran deep in the Lusk household, and the central discipline was taking care of Dad.

“At your service, sir,” Marshall announced, making the joke his dad always cringed at as he rolled the wheelchair to the driver’s-side door.

“On C,” his father said, turning his body and giving the signal for Marshall to lock the chair’s wheels and hold it in place. “A… B…”

“C…!” Marshall and his dad said simultaneously. Marshall’s father used all the strength in his arms to pivot out of the driver’s seat, toward the wheelchair, swinging what was left of his legs through the air.

In medical terms, Timothy Lusk was a double amputee. On the night of the accident, as he drove his pregnant wife to the hospital, a brown minivan that was being driven by a woman in the midst of an epileptic fit plowed into their car. Blessedly, Marshall was born without a scratch. Timothy’s wife, Cherise, was fine too. The doctors cut off Timothy’s crushed legs just below the knees.

“Careful…” Marshall said as his dad’s full weight tumbled from the car and collided with the wheelchair. He hated it when his dad rushed, but his father was always annoyed and impatient at being cooped up in snowy weather. Even though neighbors helped to shovel the Lusks’ walk, it didn’t mean they could shovel the entire town. For anyone in a wheelchair, winter was a bitch.

“Are you holding it?” his dad barked as his landing in the seat sent the chair skidding back slightly, sliding across the last bits of slush on the ground. The stump of his left leg slammed into the metal base of the armrest.

“I got it,” Marshall called back, readjusting his thick glasses and maneuvering the chair to mount the curb. Twenty years from now, every new street would be outfitted with a curb cut, and wheelchairs would weigh barely twelve pounds. But on this day, in Sagamore, Wisconsin, the curbs were unbroken and the wheelchairs weighed fifty.

In one quick motion, Marshall’s father popped a wheelie that tipped him back.

Gripping the wheelchair’s pushbars, Marshall angled the front wheels onto the curb. Now came the hard part. Marshall wasn’t strong, and he was overweight, but he knew what to do. With his palms underneath the pushbars, he shoved and lifted, gritting his teeth. His father pumped the wheels, trying to help. Marshall’s palms went red, with little islands of white where the pushbars dug in. It took everything they had…

Kuunk.

No problem. Up the curb, easy as pie.

“Galactic,” Marshall muttered.

From there, as his dad rolled in front of him, there was no plan for where they were going. His father just wanted out—strolling down the main drag of Dickinson Street… an egg sandwich at Danza’s… maybe a stop in Farris’s bookshop. But all that changed when Marshall’s father said, “I gotta go.”

“Whattya mean?” Marshall asked. “Go where?”

“I gotta go,” he said, pointing down. But it was the sudden panic in his father’s voice that set Marshall off.

“You gotta poop?” Marshall asked.

“No! I gotta pee.”

“So don’t you…?” Marshall paused, feeling a rush of blood flush his face. “I-Isn’t that what the bag’s for…?” he asked, tapping the outside of his own left thigh, but motioning to the leg bag his father wore to urinate.

“It ripped,” his father said, scanning the empty street and still trying so hard to keep his voice down. “My bag ripped.”

“How could it rip? We haven’t even—” Marshall stopped, glancing back at their car. “You tore it when you got out of the car, didn’t you?”

Racing behind his dad and grabbing the pushbars, he added, “Now we gotta get back in the car and go all the way home…”

“I won’t make it home.”

Marshall froze. “Wha?”

His father stopped the wheelchair, keeping his head down and his back to his son. He’d say these words once, but he wouldn’t say them again: “I can’t make it, Marshall. I’m gonna have an accident.”

Marshall’s mouth gaped open, but no words came out. For most of his life, because of the wheelchair, he had been nearly at eye level with his father. But he’d never noticed it until this moment.

“I can help you, Dad.” Grabbing the pushbars, Marshall spun the wheelchair around, running hard up the sidewalk. The closest store was Lester’s clothing store.

His father was silent. But Marshall saw the way he was shifting uncomfortably in his seat.

“Almost there,” Marshall promised, running hard, his head tucked down like a charging bull.

There was a loud krunk as the legs of the metal wheelchair collided with the concrete step.

“I need help! Open up!” Marshall shouted, rapping his fist against Lester’s glass door. The small bell that announced each customer rang lightly at the impact.

“Dad, tip back!” Marshall yelled as Dad popped a wheelie, and one of the employees, a thirtysomething woman with bad teeth and perfectly straight brown hair, opened the store’s front door.

“It’s an emergency! Grab the front of the chair!” Marshall yelled as the woman obliged, bending down. He jammed his own palms underneath the pushbars. “On C…” he added. “A… B…”

There was another loud krunk as the back wheels of the chair climbed the first step, wedging just below the second.

“Almost there! Just one more!” Marshall said.

“I’m not gonna make it,” his father insisted.

“You’ll make it, Dad. I promise, you’ll make it!”

“Sir, you need to stop moving,” the employee added, getting ready to lift again.

“Here we go,” Marshall insisted, his voice cracking. “Last one. On C…!”

“Marsh, I’m sorry… I can’t.”

“You can, Dad! On C…! ” Marshall pleaded.

His father shook his head, his eyes welling with tears. As he clutched the armrests of his chair, his hands were shaking, like he was trying to claw his way out of his skin… out of the chair… Like he was trying to run from his own body.

“A… B…”

With one final krunk, the wheelchair slammed and bounced over the store’s threshold, a wave of warmth embracing them as they rolled inside.

In front of them, Marshall saw a crush of customers, almost all of them moms with kids, weaving between the rows of clothes racks, all closing in on them.

It was all okay.

“Hold on, I think something spilled,” the employee announced.

The sound was unmistakable. A steady patter that drummed against the wood floor. When he heard it, Marshall didn’t look down. He couldn’t.

“Oh God,” the employee blurted. “Is that—?”

“Pee-pee…” A five-year-old girl began to giggle, pointing at the small puddle growing beneath Marshall’s father’s chair.

From where he was standing, behind the wheelchair as he clutched the pushbars to keep standing, Marshall could see only the back of his father. For years, he had wondered how tall his dad actually was. But at this exact moment, as his father shrank down into his seat, urine still running down and dripping off the stump of his leg, Marshall knew that his father would never look smaller.

“Here…” a quick-thinking customer called out, pulling tissues from her purse. Marshall knew her. She worked with his mom at the church. The wife of Pastor Riis; everyone called her Cricket. “Here, Marshall, let us help you…”

In a blur of guilt and kindness, every employee and customer in the shop was doing the same, throwing paper towels on the mess, making small talk, and pretending this kind of thing happened all the time. Sagamore was still a small town. A church town. A town that, ever since the Lusks’ accident, always looked out for Marshall… and his mom… and especially for his poor dad in that wheelchair.

But as the swell of women closed in around him, Marshall wasn’t looking at his father, or the puddle of urin

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...