- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

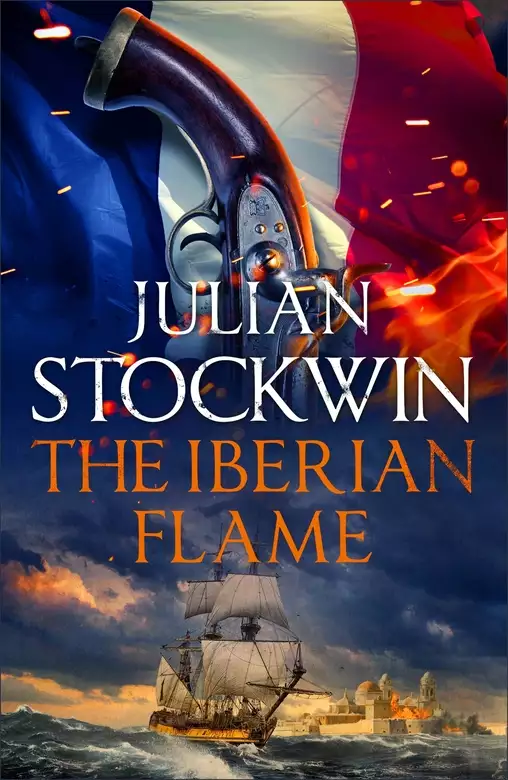

Synopsis

1808. With the Peninsula in turmoil, Napoleon Bonaparte signs a treaty to dismember Portugal and put his brother, Joseph, on the throne of Spain. Meanwhile, Nicholas Renzi, the Lord Farndon, undertakes a deadly mission to stir up partisan unrest to disrupt this Napoleonic alliance with Spain. Thrust into the crucible of the uprising, Captain Sir Thomas Kydd is dismayed to come up against an old foe from his past - now his superior and commander - who is determined to break him. Bonaparte, incensed by the reverses suffered to his honour, gathers together a crushing force and marches at speed into Spain. After several bloody encounters the greatly outnumbered British expedition have no option other than make a fighting retreat to the coast.

Release date: June 14, 2018

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Iberian Flame

Julian Stockwin

*Sir Thomas Kydd, captain of HMS Tyger

*Nicholas Renzi, Earl of Farndon, friend and former confidential secretary

Tyger, ship’s company

Others

Not forty miles from Paris, the Château de Fontainebleau lay in pompous repose. Before the Revolution its richly ornamented rooms had echoed to the pampered and carefree gaiety of the court of King Louis XVI. Now, a solemn and purposeful mood prevailed under its new occupant, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

The palace was ancient and vast, set among magnificent gardens and fountains. A pale stone edifice, it was filled to breath-taking resplendence with loot seized from every conquered nation. A matchless display of pomp and imperial might, it also served as a receiving place for the procession of defeated kings, wavering allies and helpless supplicants, who made their way to the centre of power of the civilised world.

Sitting stiffly in the gilded and sculpted Salon de Réception, Eugenio Izquierdo was not immune to its overpowering effect. An envoy of the King of Spain, His Catholic Majesty Carlos IV, he was a loyal and valuable ally who could count on respect and honour. Yet he quaked to think that in a short while he would be called into the Grand Council Chamber to stand before the Emperor himself.

He knew that Bonaparte usually worked alone in a modest study from dawn until long into the night, no detail too slight for his attention. He was served by a corps of devoted and ambitious marshals and functionaries. When the military genius appeared in the council chamber there would be no time for prevarication, pretence or airs: it would be down to the essentials, which had to be flawless in detail and, above all, have at their core the overriding interests of the Emperor.

Izquierdo had been trusted by Spain to lay before Bonaparte a proposal that would bring the two nations closer than ever before: a daring plan to seize a crown and nation for their common devouring. It should be an irresistible lure to the great man now at the height of his powers and chafing at the irritations arising from the impudence of the last nation in Europe to defy him, Great Britain. He hoped for a good hearing – but what if he were out-foxed by the wily victor of Tilsit? Known for his unpredictable cunning, Bonaparte might well take the plan and, ignoring Spain, move alone to secure the prize.

But his master, Manuel Godoy y Álvarez de Faria, first minister to Carlos IV, had foreseen this possibility. The relationship was not to be a loose understanding open to interpretation. Izquierdo had to see to it that he secured a formal treaty between sovereign powers that spelled out not just the distribution of spoils but the duties and obligations of both, such that there could be no going back on the word of a principal.

Izquierdo knew it would take every nerve in his being to stand before the conqueror of the world to demand such a condition.

He heard voices and the scrape of chairs in the next room. Heart in his mouth, he waited. The doors swept open and Marshal of the Palace Géraud Duroc appeared in all his magnificence. ‘His Imperial Majesty is now in audience,’ he announced coldly.

Five days later, weak with exhaustion but buoyed with exhilaration, Izquierdo sat at his desk and began to write.

For Godoy, it had been a wearisome and nerve-racking wait. His hold over the amiable and ageing King was undiminished, but this shaking of the foundations of the proud traditions and long history of Spain by an outsider threatened the old order – and who knew when it would settle to the familiar ways once more? This daring proposal to Bonaparte must succeed.

The unwelcome war between Napoleon’s France and her ancient rival England had caused untold ruin to the economy, not the least being the severing of ties with their South American colonies by the marauding Royal Navy, with the flow of silver and produce virtually cut off. Spanish troops had been taken up by Bonaparte to far parts of the world to aid in his conquests and a subsidy of millions in silver reales had been demanded.

He’d had to play off factions, keep grandees satisfied with tawdry honours and, by a network of spies and informants, watch for unrest and discontent in the sprawling, rugged and individualistic land that was Spain. Godoy, known as the ‘Prince of the Peace’, was the most hated of the king’s advisers. Ironically, his enemies included those who stood to lose most if he failed – the ancient lineage, the haughty aristocracy who hankered after the days of Spain standing astride the world, a handful of conquistadors carving out vast empires in a new continent to the glory of God and the Spanish Crown.

Yet as long as he retained the unquestioning trust of the King he was safe, and this he ensured by interpreting the buzz and confusion of the outside world to him in a soothing and glib fashion, every so often uncovering some plot or intrigue to demonstrate his loyalty and devotion. He had early taken the precaution of becoming the Queen’s lover, the sottish woman insatiable, a trying burden now she was in her fifties, with nothing to do but plot.

‘Excellency.’

It was a messenger – and he bore a missive. Swallowing his apprehension Godoy held out his hand then waved the man away and retired to his desk, almost afraid of what he would read.

A quick scan reassured him and, in rising excitement, he took in the hurried phrases.

He’d been right to entrust Izquierdo with the business: Napoleon Bonaparte had taken the bait.

In his eagerness he’d been willing to make a binding agreement, the Treaty of Fontainebleau, and in it was detailed the formal dismembering of the corpse of Portugal, now bereft of its sovereign, who had fled to Brazil.

Portentously, the Emperor had pronounced that: ‘The name of Portugal is to be removed from the list of nations’, the land divided in thirds between them. Oporto and the north would become the kingdom of Northern Lusitania and go to the young King of Etruria. The centre, including Lisbon, was to be administered by France until the conclusion of a general peace. But gloriously, wonderfully, all of southern Portugal, including Alentejo, was to be made an independent principality … under the rule of one Don Manuel Godoy, to be styled Prince of the Algarves.

In lesser paragraphs there was detail on how it was to be accomplished. With the gracious permission of King Carlos, French columns would enter Spain, and thereby be made quite safe from the predacious Royal Navy, enabled to march overland to join in a descent on helpless Portugal from both north and south. It was expected that the whole affair could be concluded in no more than small months.

At last – no more waiting. In a paroxysm of impatience Godoy got to his feet. There was no point in delay: he would get the business under way immediately.

‘Chancellor Godoy, Majesty.’

‘Oh. Come in, mi primo,’ King Carlos grunted genially, holding his arms high as his slim-fitting leather hunting surcoat was eased on. ‘You have something for me?’

Godoy had timed it well. Affairs of state were a tiresome intrusion when the hunting field beckoned, as it so often did. It shouldn’t take long. ‘Good news, sire, much to be welcomed in these parlous times. An initiative I’ve caused to be raised before the French Emperor has been received with a pleasing degree of acclamation.’

‘Really. Then well done, Godoy. Er, what’s it all about?’

‘Bonaparte is restless, seeing Portugal without a ruler yet flouting his offers of friendship – and, worse, seeking to plot with the British to our common distress. There is a solution I have humbly offered, which he has seen fit to accede to. It is, sire, the answer to centuries of Spanish humiliation – no less than the final unifying of the Iberian peninsula under our banner.’

‘What can you mean by this, Godoy? How can—’

‘In return for a fair division of the proceeds of the dissolution of the Portuguese nation into a Spanish province, he will provide sufficient troops to join with us in our reordering of the progress of history. For this he undertakes to enact a grand treaty between our two nations, to remain secret until we are ready to march.’

The King paused, his face comically pulled out of shape by the tight surcoat inching its way on. ‘That’s all he wants?’

‘That, and permission to march to Portugal through Spain, thereby defying the English fleet.’ He allowed his voice to acquire a more reverential tone and went on, ‘He does aver that such will be the resulting great accession of territory to the Spanish Crown that it may be necessary henceforth to refer to the King of Spain as emperor – his suggestion is “Emperor of the Two Americas”, sire.’

The coat finally settled in place while the King blinked happily. ‘A fine and statesmanlike resolving of an ancient problem,’ he pronounced at length. ‘What should I do?’

‘Merely the ratifying of the treaty will answer, sire. I’ve given the clauses my personal care and attention so you may be sure there will be no difficulties.’

‘Yes, yes, I shall. You’ve done very well, mi primo, and let the world know how grateful I am for your ministry. Is there aught else?’

Godoy’s face fell, his features carefully sorrowful. This final move would set the seal on a brilliant stroke, serving to rid himself of his deadliest and until now untouchable adversary.

‘Sire, why is it that the gods raise us up with one hand only to cast us down with the other?’

King Carlos frowned. ‘There is an impediment to the treaty?’

‘No, sire,’ he hastened to say, ‘rather it is a matter of personal sadness that I feel obliged to divulge to you.’

‘You can tell me, old friend.’

‘My man in Fontainebleau, while in the process of negotiation, discovered a grave and sinister design, no less than your deposing and replacing by another more pliable to the foreign cause.’

‘Have you the details?’

‘As of last evening, unhappily, I have, sire.’

‘The wretch shall be made to pay for his villainy!’

‘It is in truth naught but an attempt to bind Spain for ever to France through an unequal and demeaning marriage.’

‘Deposing – what in Heaven’s name is this damnable roguery?’

‘Majesty, it is the act of one who has agreed – in writing – to take whomsoever the French Emperor chooses as pledge of loyalty and obedience.’

‘He shall die, of course. Who is he – do I know the treasonous Judas?’ he spluttered.

‘Sire, it grieves me to say it but we have the evidence that it is the foolish intriguing of none other than … the Prince of Asturias.’ The King’s son Fernando. Impatient heir and implacable foe of Godoy in whatever he did.

‘No!’

‘I fear it be so, sire. Acting on information received, I made search of the royal apartments and found certain letters that shall be laid before you that are unanswerable proof of his perfidy. Shall I …?’

‘Seize him and take him to El Escorial,’ King Carlos said heavily. ‘He shall be dealt with.’

Luxuriating in the satin caress of the big four-poster bed, Godoy smiled indulgently at his mistress. ‘As it was a coup rarely seen, Pepita. In one afternoon I have vanquished that toad Fernando but much more than that – to be made a prince of Spain with a demesne of my own to rule as I please!’

‘Prince of the Algarves,’ murmured Pepita, sleepily. ‘I like that. Does your wife still have to be with us?’

‘As crowned head I shall put her from me, mi pichóncita,’ Godoy said airily. ‘Besides which, you plainly haven’t deduced what all this will lead to.’

She wriggled round to see him more clearly. ‘To more? Tell me.’

‘You really want to know?’ he teased.

‘If it touches on you and me, of course.’ She pouted prettily.

‘Then I shall tell you, cariño. After so much hard striving, the biggest prize of all is within my reach.’

‘Yes, yes, go on.’

‘With the heir to throne now disgraced, and as the only Prince of Spain not in the royal line of that old imbecile, there are many advantages to my acceding … to the throne myself.’

‘You!’ she squealed.

‘I.’

‘But …’

‘I will not weary you with details, Pepita, but there’s one that stands above and beyond all others.’

‘Tell me!’

‘Consider this. I am not a Bourbon. The French exerted themselves to extraordinary lengths to rid themselves of that decrepit bloodline, and Emperor Napoleon would like nothing better than to ally himself to one not tainted by such. As prince, I will be in the line of succession. He will undoubtedly bring much pressure to bear on the Cortes that will, in the end, see me King of Spain!’

‘Very good. You may stand down sea watches, Mr Bray,’ Captain Sir Thomas Kydd told his first lieutenant.

He took a deep breath and looked around in satisfaction. After her far voyaging, Tyger had picked up moorings in the broad stretch of water fed by the river Tamar between Devon and Cornwall that went on into Plymouth Sound. On its eastern bank was the well-equipped King’s Dockyard. While the ship’s small hurts were attended to, all would have time for leave and liberty.

And not far inland, over the soft green rolling hills, his heart had its home: Knowle Manor, nestling in the Devonshire countryside, now the seat of Sir Thomas and Lady Kydd.

Persephone would not be expecting him – the hastily mounted Northern Expedition into the Baltic that had called him away had had all the signs of a savage and protracted confrontation. As it happened, it was now over, leaving Admiral Saumarez and his Baltic Fleet predominant at sea.

Some ships had been released to return to their original duties. For Tyger this meant rejoining Admiral Collingwood’s Mediterranean Fleet and its eternal blockade of Toulon and the western seaboard of Europe – but that would come later. First, liberty!

For her ship’s company it would be the delights of an English shore where they could raise the wind a-rollicking in a sailors’ town to drown memories of gales and iron-bound coasts, a shipmate lost to the sea or the rage of battle. And with prize money to spend they would make it a famous time.

And for her captain, a release of shipboard cares. With his valet Tysoe at pillion, he took coach to the pretty village of Ivybridge, then a hired trap from the London Inn, his heart thudding with anticipation. The road followed the crystal waters of the river Erme, then veered off into the wooded foothills below the moors before the quaint loveliness appeared of Combe Tavy, with its pond and goose green.

Without stopping, they trotted up the little country road … that left-hand bend … the enfolding woods and then … the ancient wall and the gatehouse, its arch bearing the precious legend, Knowle Manor.

Tysoe brought the horse to a walk as the trap ground grittily along the driveway to the entrance – but Kydd had seen a female figure at the roses by the creeper-clad walls look up in surprise. In a single mad movement he vaulted from the seat and raced forward, crushing her to him.

‘My darling – my love! Seph, I’ve so missed you!’

‘My dearest … you’re home! My sweet, my—’ Her voice broke with emotion.

They kissed, long and passionately.

‘Oh dear,’ she said shakily, brushing the dark earth from her gardening apron, ‘and I’m not fit to be seen.’

‘Seph, you’d look as comely in a pedlar’s rags, my love, never doubt it,’ he said tenderly, kissing her again and taking her arm.

A beaming Mrs Appleby, the housekeeper, held open the door, then made much of primping the cushions on the two comfortable armchairs by the fire. ‘Aye, but you an’ the captain’ll have much to talk on, so I’ll leave ye be.’

Kydd dragged his chair closer and they sat, hand in hand, lost in the moment.

‘There, my dear. My very own kitchen garden.’ Persephone beamed.

The morning sun was warm and picked out the neat rows of plants. They meant nothing to Kydd, but he smiled winningly and expressed his admiration. To his rescue came a distant memory of Quashee, a mess-cook whose flourishing of his ‘conweniences’ had been a legend in the flying Artemis on their round-the-world adventure.

‘You’ve planted an adequacy of calaminthy, of course,’ he said, in a lordly tone. ‘A sovereign physic in any situation.’

‘Calaminthy? I don’t think I have.’ She frowned uncertainly, in the process managing to wring his heart with her loveliness.

‘Oh, er, the common sort would know it as the basil, m’ dear.’

‘Basil?’ She shook her head. ‘But the rosemary is growing splendidly, and tonight you’ll taste it in Mrs Appleby’s venison ragout.’

The improvements she’d made were impressive. The garden was now tamed, the front of the manor with its red Tudor brick freed of the overgrown ivy, but with enough left to frame the darkened oak doors. The weathercock atop its tower was now proud and square and the lawn had been meticulously mown.

Kydd made acquaintance with Persephone’s new horse Bo’sun, the noble brown face, dark ears flicking, looking at him curiously. He knew his wife was an excellent rider and judge of horses but this beast was exceptionally handsome. A full chestnut of some fifteen hands and gleaming with condition, its lithe musculature spoke of effortless speed and endurance.

‘We’ll lease a mount for you while you’re home, Thomas,’ she made haste to assure him. A horse was an expensive article and another could not be justified when he was away at sea for so much of the time.

He beamed, looking forward to riding with her on the moors. ‘Yes, Seph. We’ll see to it directly.’

Workmen were still busy on the small buildings at the back: a charming summer house and a discreet garden shed where Mr Appleby was preparing his pot plants.

‘I want to talk to you about a pavilion, Thomas dear,’ she murmured, as they roamed arm-in-arm along the wilder southern fringes of their property. She pointed out a fine place for a small private shelter with a picnic view into the steep, wandering valley of the Tavy.

Back inside the house, a shy maid stood aside as Persephone asked him anxiously if he approved her choice of dinner service – a Spode setting of exquisite artistry and, to Kydd’s eyes, perfectly attuned to the bucolic placidity of Knowle Manor. Not the pompous gold-lined ornateness of Town but joyous limned English flowers and butterflies on delicately formed ivory porcelain. The selection of cutlery had been put aside until they could consult together on a trip to London.

Combe Tavy folk soon knew that the squire was back from his sea wanderings, and in the Pig and Whistle the one-eyed innkeeper, Jenkins, grinned from ear to ear as he served the alarming number of villagers who had found it convenient to rest from their labours.

Kydd heard from the soft-spoken old sheep-farmer, Davies, of the loss by braxy over the winter of three of his flock, which a long-winded account put down to their consuming grass while still frost-speckled. The beady-eyed thatcher, Jermyn, came in with a harrowing tale of a roof fire in the remote hamlet of Horrabridge that had had him trudging over the moors in wind and sleet of an unpleasantness that a gentleman like Kydd could never conceive.

After politely asking after him, others listened as he contributed a morsel concerning the perils of horse-riding on the hard sea-ice of Finland and the grievous conditions for reindeer looking for forage under snow that had lain undisturbed for four months. It left them bemused as they quaffed their moorland ale.

The days passed in a sweet warmth that Kydd could feel imperceptibly rooting him to the place. Curling up together in front of the fire, he and Persephone made comfortable decisions about their hearth and home, such as where the grand portrait of Knowle Manor she had painted should be hung.

But Kydd’s attempts to win over the sleek tabby, Rufus, who held sway over this his kingdom were forlorn.

‘One night during an awful storm he suddenly appeared as though it were his long-lost home,’ Persephone told him fondly, picking the cat up. ‘Licked himself all over for an hour in front of the fire and settled in. I hadn’t the heart to turn away the rascal.’ The creature accepted a twiggle of his ears, while continuing to stare at Kydd with striking lambent eyes. ‘He’ll be used to you by and by.’

Persephone didn’t press him for details of his adventuring but Kydd suspected that she was guessing at what he didn’t say so strove to round out the details. Coming from a naval family, she knew the sea cant and did not require tedious explanation. He found himself recounting a dramatic clawing off a lee-shore with the familiarity of a seasoned mariner and saw by her expression she understood perfectly.

‘I’m blessed beyond my deserving,’ he murmured to her, not for the first time.

The morning was clear and warm when Kydd and Persephone set out for Tavistock across the moors, a score of miles distant. They took it at a brisk canter, spelling their horses at the Goodameavy stables, where Kydd had once despaired of her feelings for him.

It was Thursday, the pannier market was in full swing and Kydd let the bustle of the town envelop them. Tavistock was inland, between Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor. Surprisingly, the town’s most famous sons were all mariners. The chief was Sir Francis Drake, whose seat of Buckland Abbey was close by. Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the colonist and explorer lost at sea, would have had his last memories of home as Kydd was seeing it, and Grenville of Revenge was suzerain of Buckland at the time of his famous last fight. His cousin Sir Walter Raleigh had grown up nearby, and many more had found their calling upon the sea from the towns and villages on the road to Plymouth.

Sir Thomas and Lady Kydd wandered together among the stalls and booths, the produce and crafts of Devonshire on exuberant show, the hoarse cries of the stallholders mingling with the babble of market-goers, jostling good-naturedly and enjoying the delights of the day. Folk were of all stations in life: smock-clad farm workers, beefy merchants, gentlemen and their ladies.

The thick, pleasing odours of country life eddied about them, and Kydd mused that he couldn’t be further from the stern reality of the war at sea. With a beautiful woman on his arm and the day theirs, he would be pressed to bring to mind a heaving deck, taut lines from aloft, the menacing dark blue-grey of an enemy coast on the bow … This was another place, another world.

‘Oh, how quaint!’ Persephone exclaimed, admiring a pinafore extravagantly interwoven with lacework of a previous age, unusual on such a garment. She fingered it reverently, the seller, a man, watching her silently.

Kydd’s gaze wandered. There were many more attractions and they could easily—

Standing motionless not more than a dozen yards away, a gentleman in plain but well-cut attire was regarding him gravely.

Kydd didn’t know the man … or did he? The distinguished greying hair, the direct, unflinching hard gaze, the stern, upright bearing … Like the master of a ship …

It couldn’t be, but it was: the defeated captain who had met him on the deck of the last of the three frigates Tyger had overcome in her epic combat in the southern Baltic the previous year. Preussen, yes – a French-manned Prussian and commanded by one Marceau.

After a moment of shock at the sudden clash of worlds, Kydd gave a polite bow of recognition, which was solemnly returned. Clearly the man was not on the run and neither was he closely escorted.

He walked amiably up to Kydd and spoke in French. ‘Capitaine de vaisseau Jean-Yves Marceau,’ he offered, the eyes as Kydd remembered, cool and appraising. ‘Guest of sa majesté as a consequence of—’

‘Captain Sir Thomas Kydd, and the circumstances I do remember with the deepest of respect, sir,’ Kydd answered in French. So Marceau was a prisoner of war, and as an officer had no doubt given his parole to allow him this freedom. But an educated and polished gentleman of France in Tavistock?

Persephone regarded them curiously. ‘Oh, this is Lady Kydd, my wife. My dear, this is Captain Marceau whom I last met on the field of honour.’

The French captain lifted her gloved fingers to his lips. ‘Enchanté, m’ lady.’

‘A singular place to meet you again, M’sieur le capitaine, if I might remark it,’ Kydd continued.

Marceau gave a small smile. ‘Having duly lodged my parole with your esteemed Transport Board I was assigned this town to reside, always within its boundaries, in something approaching comfort and refinement, here to wait out the present unpleasantness until it be over.’

‘A civilised arrangement, I’m persuaded,’ Kydd responded. Did captured English naval officers in France have the same privilege? But then a surge of compassion overtook him. This was a first rank sea officer, transported to captivity in the countryside of his enemy. Robbed of the graces and enlightenments of his patrimony, he was eking out his existence, probably of slender means and seldom to hear the language of his birth.

The man bowed, a glimmer of feeling briefly showing.

‘Yet a hard enough thing for an active gentleman,’ Kydd continued. ‘May you travel, sir, visit others at all?’

‘Should I stray further than the one-mile stone on any road away from Tavistock then I shall be made to exchange my present existence for that of the hulks,’ he replied evenly.

It was an imprisonment but of another kind, and Kydd impulsively warmed to the man – wryly recalling that it was his actions that had placed Marceau here.

An absurd thought surfaced and he found himself saying, ‘Then my invitation to your good self of a dinner evening at my manor must therefore be refused?’

Persephone looked at him sharply but he affected not to notice.

Marceau stiffened, then bowed deeply. ‘Your most gallant and obliging politeness to me is deeply appreciated, Sir Thomas, but in the circumstances I should look to be denied.’

‘I regret to hear this, sir.’

The Frenchman paused, looking at him directly. ‘Yet if I trespass further upon your good nature there is perhaps a means to that end.’

‘Say on, sir!’

‘The parole agent of this town may be approached and, for a particular occasion, has the power to grant licence, I’m told.’

Mr Nott was at first astonished, then gratified to make acquaintance of the famed frigate captain.

‘As your request is not unknown, Sir Thomas,’ he allowed, pulling down a well-thumbed book from the shelf above his desk, ‘but seldom granted, I fear.’

‘Why so, sir? I would have thought it a humane enough thing.’

‘Ah. Then you are not aware of the parlous state of affairs in the matter of the confining of prisoners of war in this kingdom.’

It cost Kydd nearly an hour’s listening to the man but it was a sobering and enlightening experience.

The arcane eighteenth-century practice of making such prisoners the responsibility of the Sick and Hurt Board of the Admiralty had been superseded by the equally obscure assigning of them to the Transport Board, known more to Kydd as the procurer of shipping for army expeditions. Captured enemy officers were offered parole or made to suffer incarceration in one of a number of prisons in Britain. Foremast hands had to endure the hulks or prison without the possibility of parole.

Kydd had shuddered at his first sight of the distant lines of hulks in the Hamoaze, and he remembered the Millbay prison louring across the bay from his previous lodging at Stonehouse.

Nott’s duties were to muster his charges regularly, to issue them weekly with the sum of one shilling and sixpence per diem in subsistence, and to handle private remittances, with all correspondence to go through him for censoring before it reached the post office. For their part the French found modest lodgings, which they undertook to return to by curfew, generally eight at night, and to refrain from activity that could be deemed in any way seditious.

He received little enough thanks, Nott complained, and there were increasing numbers absconding, breaking parole, and presumably finding their way back to their home country. It was a growing scandal, especially, as Kydd knew, it was a matter of a gentleman’s honour. The France of Napoleon was a different nation from that of earlier days.

‘Captain Marceau is still here,’ Kydd said pointedly.

‘How do you mean, sir?’

‘If he’d wanted to break his parole he’s had a year or more to do it. I fancy an evening entertainment will not see him inclined to run on its account.’

It cost Kydd a ten-guinea bond but Knowle Manor would know no less a personage than a French frigate captain as a guest to dinner.

The evening was accounted a success from Marceau’s arrival and extravagant admiration of the oil painting in the hallway, portraying the sublimity of Iceland by an artist unknown to him, to the exquisite manners he displayed at table when good Devon mutton made its appearance, accompanied by a sauce whose piquancy had him exclaiming.

Afterwards, when the cloth was drawn and a very acceptable La Rochefoucauld cognac was produced, the atmosphere warmed further. A dry smile followed Marceau’s complimenting Kydd’s taste in brandy, both leaving unsaid tha. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...