- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

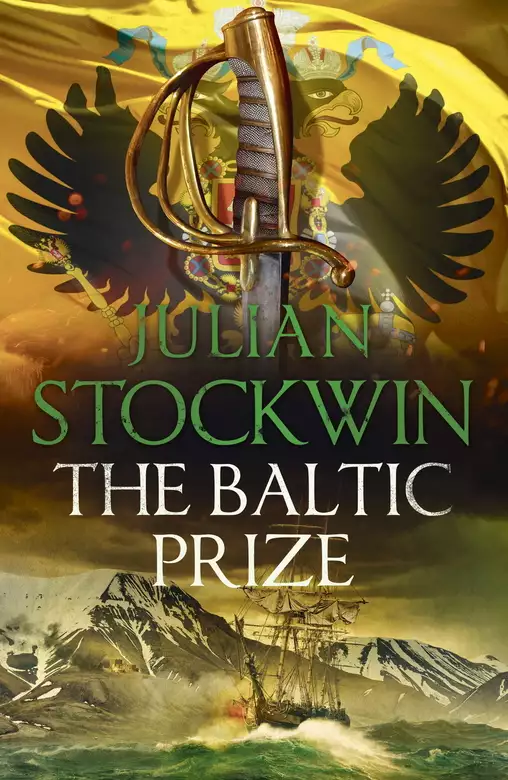

1808. Parted from his new bride, Captain Sir Thomas Kydd is called away to join the Northern Expedition to Sweden, now Britain's only ally in the Baltic. Following the sudden declaration of war by Russia and with the consequent threat of the czar's great fleet in St Petersburg, the expedition must defend Britain's dearly-won freedom in those waters. However Kydd finds his popular fame as a frigate captain is a poisoned chalice; in the face of jealousy and envy from his fellow captains, the distrust of the commander-in-chief and the betrayal of friendship by a former brother-in-arms now made his subordinate, can he redeem his reputation? In an entirely hostile sea Tyger ranges from the frozen north to the deadly confines of the Danish Sound - and plays a pivotal role in the situation ensuing after the czar's sudden attack on Finland. This climaxes in the first clash of fleets between Great Britain and Russia in history. To the victor will be the prize of the Baltic!

Release date: November 2, 2017

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Baltic Prize

Julian Stockwin

At the time Saumarez was blamed for not bringing about a full-scale fleet action but he arrived on the scene just one day later, narrowly missing Khanykov’s fleet at sea. The reason for his delay is one of the most remarkable and little known tales of the war.

In the army of Napoleon there were troops from many countries and most of those massing in Denmark for the invasion of Sweden just across the water were those of his ally, Spain. Exploiting unrest caused by rumours of Bonaparte’s move to place his brother Joseph on the throne, the shadowy figure of James Robertson, a Scottish Catholic priest, was infiltrated into Denmark to subvert the Spanish field commander, the Marquis de la Romana. He did so, and in a feat of daring and secrecy, the Royal Navy landed parties of seamen in the southern Danish islands and extracted nearly ten thousand front-line troops from under the very noses of the French, thereby making the invasion of Sweden impossible.

Saumarez was torn between sailing to meet the Russians or supporting this absurd-sounding clandestine mission; his decision to do the latter almost certainly cost him a great victory, fame and a peerage, but he knew the greater issue was the Baltic trade and a wounded Tsar would have turned against him.

This victory, however, secured the Baltic for Britain and it marked the beginning of the end for Bonaparte, for it was Tsar Alexander’s refusal to enforce Napoleon’s Continental System that infuriated the emperor enough to embark on the fatal 1812 invasion of Russia. On Khanykov’s return, this Russian admiral faced court-martial in Moscow for cowardice, and in an autocratic and brutal regime was unaccountably able to get away with a sentence of demotion to ordinary seaman for one day. In a tangible reminder of the occasion, the entire stern gallery section of HMS Implacable is on display at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

After his escape Sir John Moore, that prickly, stiff-necked military figure, took all his men back to England; he met fame and a hero’s death at Corunna later in the year.

The last Danish big-ship fight is still remembered more for the loss of the plucky Willemoes in Prinds Christian Frederik, the young man who had stood defiant on a gun raft against Nelson in Copenhagen. Walking through the remote and sandy hamlet of Havnebyen on Sjællands Odde, you will come across the roads Willemoesvej and Jessensvej, and in the wardroom of the naval artillery school at the tip of the peninsula, with its long-fanged reef, there are further memories.

Johan Krieger, the fiery gunboat leader, has his small share of immortality: a charming portrait in the naval museum in Copenhagen reveals him as a chubby, mischievous soul, who would no doubt have been a fine and jolly messmate at Nyholm, but it is probably fair to say he caused the British more grief than any other Dane during the ‘English Wars’.

The attack on Kildin by Nyaden frigate, on which I based Kydd’s storming ashore, was mentioned in The Times as the first ever British incursion on Russian soil and, with other isolated Arctic incidents, would be the last until the failed 1919 intervention against the Bolsheviks. It is a crushingly desolate place and charts of the island are difficult to find: today it is the unhappy graveyard of discarded nuclear submarine engines of the Soviet fleet, but its isolation is a boon for various exotic Arctic fauna.

The Sveaborg fortress still exists and is a popular and interesting attraction in Helsinki under the Finnish name of Suomenlinna, its sudden capitulation fuelling endless speculation and conspiracy theories among Swedish writers. Cronstedt was a genuine hero, leading Sweden to the crushing defeat of Russia at the sea battle of Svenskund some years before. However, after being embayed in Malmö and unable to come to the aid of the Danes fighting Nelson he was publicly humiliated by the Swedish king, Gustav IV Adolf, and rusticated to Sveaborg. His supporters state that there is no evidence from the years after the surrender of a change in lifestyle, indicating bribery or a sell-out, but this in fact would be consistent with the case that he in turn had been cheated by the Russians in the matter of gold buried on the parley island …

The capture of Anholt, upon which I’ve closely based my Börnholt, has its measure of curiosity also. The island was promptly commissioned into the navy as HMS Anholt after the success of HMS Diamond Rock off Martinique several years before and the Admiralty felt impelled to send for the very same man to take charge, Commander James Maurice, who in that post later victoriously defended it against the vengeful Danes.

For the Swedes this has to be accounted their saddest hour, especially their proud navy, which at this point was riven by factions and defeatism. The Finnish war did not go well for them, at one time an audacious winter crossing by the Russian Army of the ice to the Åland islands threatening Stockholm itself. It couldn’t last and the last Vasa, Gustav IV Adolf, was deposed in a scene out of Shakespeare.

In Gripsholm Castle I visited the very room and saw the desk where his abdication was effected. The former monarch was fated to wander Europe, a king without a throne. The weak and faltering king who succeeded him lasted long enough to declare war on England and, finally, the last ally of Britain on the Continent fell. Yet in large part due to the truly exceptional talents of Saumarez the war was conducted without a shot fired, the enemy victualling and supplying their very opponents, with Matvig and other secret bases conveniently overlooked. Above all, the Baltic trade continued without a tremor, even with the British now completely surrounded by hostile nations. Then, because of the state of war against England, the Swedes were obliged to source a new king from closer by, namely Prince Bernadotte, who, once on the throne, felt able to defy Bonaparte and even take up arms against his own countrymen, defeating them roundly.

Yet of all the bizarre oddities of this campaign none can match that of the lengths to which merchant-ship captains went to get their cargoes through. To circumvent the treasonable act of trading with the enemy, application was made for a private licence to do so. At first issued sparingly, by the end of the war these were turned out by the tens of thousands and were accepted on sight by British cruisers, while false papers were carried to get them into an enemy port. The ‘simulated papers’ were produced by skilled forgers in speciality firms situated in London, the latest information passed on from the Continent, and were so good that before long Lloyds would refuse insurance unless a ship could show a set.

Other scams were introduced: the Danish island of Heligoland, captured by the British, was turned over to the sole industry of cargo laundering where, in an area not much bigger than Hyde Park, colossal amounts of cargo from England were repackaged and re-stowed in a ‘neutral’ ship before being sent into Europe. Napoleon’s officials were helpless to stop this and before long became hopelessly corrupt – Prince Bernadotte considerably helped his offer for the Swedish throne by providing a massive state loan from the proceeds of his involvement. Insurance premiums fell, from 40 per cent when Saumarez first entered the Baltic to the usual two to three per cent when these measures got into their stride.

The French, without command of the sea, found their own ships levied a prohibitive 50 per cent or more and were effectively wiped from the trade routes. Grotesquely they found protection by going as ‘neutrals’ in Saumarez’s convoys and, flourishing genuine papers as simulated ones, they were able to insure their vessels at Lloyds, an English court ruling with impeccable fairness that merely being an enemy did not disqualify them from recovering on a duly accepted policy. It did them little good: under eye they had no chance of loading French export goods and ended taking British goods into the Continent, leading to the established fact that Bonaparte’s troops were clothed and booted on their march to Moscow by the factories of the Midlands.

Great Britain owes more than it realises to Admiral Saumarez. The Baltic trade, the only conduit left to it, would have, if severed, brought about the strangulation of the country and the end of the war. As it turned out, the trade swelled and blossomed and by the end of the war had generated a taste on the Continent for British trade goods that spread far and wide and which, after the war, led to an advantage that left Britain in the Victorian era the greatest commercial nation on earth.

I first came across this great sailor and diplomat while researching Treachery in Guernsey, where the lieutenant governor, Sir Fabian Malbon, was involved in establishing a fund to replace the Saumarez memorial, dynamited during the war by the German Wehrmacht.

To all those who assisted me in the research for this book I am deeply grateful. Particular thanks are due to two people. Eva Hult, archivist at the Maritime Museum in Stockholm, afforded me the great privilege of handling the actual plans of gunboats created by the gifted af Chapman, whose designs dominated the Baltic at the time this book is set. Ulla Toivanen in Finland, in a warm gesture from a stranger, readily shared insights into her country’s culture and history.

I visited many splendid museums in the Baltic region as part of the preparation for this book – but the Estonian Maritime Museum in Fat Margaret Tower, Tallinn, only an hour from Rågervik, stood out, providing a wealth of information.

My appreciation also goes to my agent Isobel Dixon, my editor at Hodder & Stoughton Oliver Johnson, designer Larry Rostant, for his superb cover design, and copy editor Hazel Orme.

And, as always, my heartfelt thanks to my wife and literary partner, Kathy.

His Majesty’s Frigate Tyger came to, her bower plunging down to take the ground at last. She carried two prisoners, Count Trampe, the Danish governor of Iceland, and Jørgen Jørgensen, its self-styled king, to be landed into the custody of Sheerness dockyard, and a new-wed lady to step ashore.

For Kydd the last few weeks had been dream-like, a procession of unforgettable scenes, from the Stygian dark landscape of Iceland pierced by the glitter of vast glaciers, the fumaroles, the blue lakes, the wheeling gyrfalcons – and the vows solemnly exchanged in a timber cathedral.

And now he and Persephone were one, man and wife; there was not a soul on the face of the good earth who was as happy as he.

‘Sir?’ Bowden, his second lieutenant, proffered a paper with a faint smile playing.

‘Oh, yes, thank you.’ Kydd dashed off a signature and, too late, realised he hadn’t stopped to check what he was signing. He collected himself: it would not do for the captain to be seen adrift in his intellects even if there were good reasons for it.

However, this was no doubt the fair copy of his brief report to be forwarded to Admiral Russell on blockade off the Dutch coast with the North Sea Squadron he’d left at Yarmouth. It told of the recent happenings in the north and the necessity to land the two main players in the drama to be dealt with by higher authorities in London. They had already been sent off, with his main report to the Admiralty, who would either detain him as a material witness or release him to resume his duties with the North Sea Squadron.

‘Ah, Mr Bowden. A favour of you, if I may.’

‘Sir?’

‘Would you be so kind as to conduct Lady Kydd to the residence of her parents for me?’

‘Of course, Sir Thomas. I would be honoured.’

With a stab of tenderness, Kydd knew that it was only the first of the many partings that sea service would demand of him but this, so soon after their marrying, would be harder than any. Feeling a twinge of guilt, he didn’t envy her what she had to do. Not only had she to let her father and mother know that she had not disappeared and was very much alive but also that she was now wed to a man they detested.

They had lunch together before she left, a quiet occasion and charged with bitter-sweet feeling – and then it was time to part. Kydd saw her over the side, and as the boat shoved off into the grey sea for the distant shore his heart went out to the lonely figure carrying his hopes and love. She waved once and he responded self-consciously, watching until they were out of sight, then went below without a word.

The Admiralty’s response, when it came, was neither of the possibilities he’d foreseen. He was not required in the matters of Jørgensen and Count Trampe but neither was he to re-join the squadron. Instead he was to hold his command in readiness for duties as yet not determined.

It was odd, a first-class frigate not snapped up for immediate employment, but he’d seen before how, in their mysterious way, the Admiralty had chosen to deploy a pawn on their chessboard to effect a grand strategic move that made perfect sense later – the tasking of L’Aurore so soon after Trafalgar came to mind. That had taken him to the Cape of Good Hope and conquest of an entire colony at the end of the world.

In a surge of delight he realised what it meant: not needed for a routine idleness and away from an admiral’s eye, he was free to take leave with his bride – a telegraphed communication with Plymouth would have him notified within an hour or so of any orders.

Blank-faced, his first lieutenant, Bray, had accepted charge of the ship and, accompanied by Tysoe, Kydd was quickly on the road for the Lockwood mansion. By now Persephone would have broken her news but as a precaution he took rooms at a nearby inn and sent on a message.

Her reply was instant: ‘Come!’

Kydd immediately set off. He had been to the Arctic regions but nothing was as frigid as the Lockwood drawing room where he was received.

‘I’m obliged to remark it, sir, I find your conduct with my daughter impossible to forgive. You have—’

‘Father, you promised …’ Persephone said, with a look of warning.

Her arm was locked in Kydd’s, and she was the picture of happiness. None but those of the hardest of hearts could have condemned her. After an awkward pause, it seemed the admiral was not to be numbered in their company and he gave a mumbled blessing on their union. At the dinner that followed he even found occasion to reprove his wife, telling her that the pair had chosen their path together and let that be an end to it.

The strained atmosphere slowly thawed and by the time Kydd had expressed his sincere admiration for the oil painting in pride of place above the mantelpiece, a remarkably accurate depiction of the sea battle of Camperdown, he and the admiral were in animated conversation discussing technical features with growing mutual appreciation and respect. Kydd was touched by Persephone’s secret smile of relief.

It took more effort to win around Lady Lockwood, who sat mutely, her eyes obstinately averted. Only a suggestion of a reception in honour of their marriage brought forth any conversation.

One more duty awaited. ‘My love, I do believe that my dear parents would find it strange if I don’t make introduction of my bride.’

‘Of course, Thomas! I’m so anxious – what will they think of me?’

Kydd held back a grin but quickly sobered. This visit of all things would reveal to her just how humble were his origins, the true status of the family into which she’d married. She knew he’d been a pressed man and probably suspected he came from yeoman stock but, no doubt in deference to his feelings, had never pursued it further. Now she would discover the truth.

Evening was drawing in when the coach made the corner and began the hard pull up the busy Guildford high street.

Kydd let the sensations of a home-coming wash over him: the old baker’s yard, the little alley to his dame school, the shops that crowded together, all smaller than he recalled but still there, quite the same, while he had changed so much. Some he barely remembered: the apothecary shop with its dusty human bones, the pastry emporium, the rival perruquier now long transformed to a haberdashery, still others. He felt her hand on his, squeezing, then caught her look of loving understanding and, yet again, marvelled at his lot in life.

The horses toiled further, and just before the Romanesque plainness of the Tunsgate columns they slowed and took a wide swing into the medieval entrance of the Angel posting-house. Persephone was handed down and immediately went back to the high street where she looked around, admiring, and exclaimed, ‘What a charming town.’

Kydd stood awkwardly by her. ‘As this was my life for so long – but I can hardly remember it, truly.’ Although he was in plain clothes, the innkeeper immediately recognised him. The best rooms in the Angel were his – and be damned to the bookings!

They sat companionably by the fire in the snug, cradling a negus, while a messenger was sent to ask if it would be at all inconvenient for him to call. His mother would fuss but at least she would have some warning. Both her children had left home: Cecilia to life as a countess, married to Kydd’s closest friend, Nicholas Renzi, now Lord Farndon, and he to fame as a sea hero. How was she coping on her own with his blind father?

As they sat together, Kydd haltingly told Persephone of his youth in Guildford: making wigs in the shop that they’d presently walk past, being brutally taken up by the press-gang in Merrow – and when, as a young seaman, his father’s failing sight had obliged him to give up the sea and return to wig-making, his soul-searing desolation cut short by Renzi’s brilliant idea to start a school on naval lines …

The thoughts and memories rushed by, and then the breathless messenger came back, wide-eyed, relaying expressions of delight: Kydd’s parents were expecting him home this very minute.

Arm in arm, Kydd and Persephone went up the little path by the red-brick Holy Trinity Church, making for the road now called School Lane. Above the school buildings the blue ensign flew proudly from a trim mast and single yard. The place looked in fine order, its neat front garden in fresh bloom, testament to his mother’s delight in flowers, a white picket fence setting it off from the quadrangle beyond.

‘Sir T, ahoy!’ came a bellow. Jabez Perrott, the school’s boatswain, stumped up on his wooden leg, with a grin that split his face in two. ‘An’ ye’re castin’ anchor for a space?’

‘It’s right good to see you again, Mr Perrott,’ Kydd said, with feeling, shaking his hand, still with the calloused hardness of the deep-sea mariner. He turned to introduce Persephone. ‘This is, um, Lady Kydd, my wife.’ He was still not used to it. ‘How goes the school?’

‘Oragious, Sir T! We had, b’ Michaelmas last, five lads as followed the sea, an’ many more who’s got their heart set on’t.’

‘Well done, sir!’ Kydd said, in sincere admiration. ‘I’ll see you at colours tomorrow.

‘Now, you’ll pardon, I have to pay duty to my parents. Carry on, please.’

With Persephone on his arm and unsure what he’d find, Kydd knocked on the door.

It flew open and his mother stood there, beaming. She hugged and hugged him, murmuring endearments, a frail, diminished figure but still full of life. ‘How do I see ye, son?’ she managed, unable to take her eyes from his. ‘Ye’re well?’

‘Very well, Ma,’ Kydd said awkwardly, then brought Persephone forward. ‘Ma, I’d like you to meet Persephone, who must now be accounted my wife.’

His mother blinked, as if not understanding. Then her eyes widened as she took in Persephone’s elegant appearance and hastily curtsied.

Concerned, Persephone raised her up and said gently, ‘Thomas is now my husband, Mrs Kydd, who I do swear I will care for with my life.’

‘Oh, well, yes, o’ course,’ she said, clearly flustered. ‘Please t’ come in, won’t ye both?’

Kydd’s father was in the parlour and, hearing them enter, rose creakily. ‘How are ye, son?’ he said, his eyes sightlessly searching for him.

‘I’m well, Father, and I’ve brought my new wife, Persephone.’

Mr Kydd jerked up in surprise. ‘Any family I knows?’ he asked at length, as she came forward and took his hands in hers.

‘No, Pa. I married her … I wed her in Iceland,’ he said, with a chuckle, then thought better of it. ‘Who comes from an old English family …’

‘From Somerset,’ Persephone put in softly.

It was all a bit much for the elderly couple and the evening meal passed in an awed hush. Kydd took his cue from Persephone, who brightly praised her first encounter with Guildford, remarking on the sights and mentioning as an aside how they had met in Plymouth and again in a foreign place, where they determined they could not be apart any longer.

‘An’ where will you live?’ his mother asked hopefully.

‘In Devonshire, where the air is bracing and healthy, and the victuals not to be scorned,’ Kydd said firmly. ‘And not so far by mail-coach, Ma.’

In the morning there was nothing for it but to muster at the main-mast, the boatswain fierce and unbending before the assembled pupils of the Guildford Naval Academy, standing in strict line, eyes agog to see the sea hero they had been told about so often.

Kydd was in uniform, albeit without his knightly ornaments, the quantities of gold lace of a post-captain quite sufficient for the occasion, and he stood next to the headmaster, Mr Partington, now a gowned and majestic dominie. His prim wife took her place behind him.

‘Pipe!’

The ensign rose in reverent silence, the squeal of the boatswain’s call piercing and clear above the muffled bustle of the town. To Kydd’s ears it was so expressive of the sea’s purity against the dross of land.

‘Ship’s comp’ny present ’n’ correct. Sir!’

‘Very well.’ Kydd stepped forward to say his piece, but he was put off balance by the scores of innocent faces before him as they waited for words of courage and hope. In desperate times at sea he’d fiercely addressed his ship’s company before battle but now he found he couldn’t think what to say.

‘A fine body of men,’ came a fierce whisper behind him. He repeated the words and she went on to hiss, ‘As fills you with confidence for England’s future … only if they faithfully and diligently pay attention to their grammar and reckonings … that the good captain-headmaster is taking pains to teach them …’

The awed students were dismissed to their lessons and Kydd was escorted on a tour of the classrooms, where he bestowed compliments and earnest assurances that the subordinate clause was indeed a handy piece of knowledge to hoist inboard for use at sea.

He was touched by the little building at the back that had been made to resemble a frigate’s mess-deck. There, industrious boys bent hitches and worked knots under the severe eye of Boatswain Perrott – and at the right and proper time took their victuals, like the tarry-breeked seamen they so wanted to be.

A civic reception was a grander occasion and, in full dress with sword and sash, Kydd spoke rousing words of confidence to the great and good of Guildford. He then accompanied the mayor out on to the town-hall balcony beneath the great clock to address the citizenry much as, long ago, after the battle of Camperdown, Admiral Onslow had invited Kydd up to join him as one who had made his victory possible.

It was unreal, a dream – he’d changed beyond all recognition since those days and needed time to take it all in.

Kydd took Persephone to see the old castle, the weathered grey stones just as massive and enduring as he remembered, then down to the River Wey, its gliding placidity reaching out to him in its gentle existence. They followed the tow-path, silent and companionable, letting the tranquillity work on them until it was time to return to his parents.

‘We have to be off now, Ma,’ Kydd said quietly, ‘to see to our estate, to set up our home.’

‘Yes, m’ darling. I know ye’ll be happy there, wi’ your Persephone. Do come an’ visit when ye can, son.’

Duty done, and knowing that their time together would be brief, they posted down to Ivybridge. There, they took horse for Combe Tavy and the old manor they had chosen. As Kydd dismounted before the dilapidated Tudor building, he was dismayed to catch the sparkle of tears in Persephone’s eyes. ‘My love – what is it? We’ll soon have the place squared away, all a-taunto, never fear.’

She clung to him, but when she turned to speak he saw she was radiantly smiling through her tears. ‘Oh, Thomas, dear Thomas! I’m such a silly, do forgive me. It’s just that I’m so happy.’

He kissed her tenderly.

The old couple caretaking were surprised to see them. ‘We thought as you’d forgotten us, sir,’ Appleby said, aggrieved. ‘The manor needs a mite o’ work, an’ that’s no error!’

‘It does,’ Kydd agreed. ‘And we will make it so, for this is our home as we shall be moving into, just as soon as we may.’

Mrs Appleby clasped her hands in glee. ‘How wonderful!’ she exclaimed. ‘To see Knowle Manor have life in it once more!’

There was no time to lose. They made tour of the house, noting what had to be done, and by the time Tysoe arrived in a cart with their luggage they had enough to set priorities. That evening they sat down to a fine rabbit pie, Mrs Appleby wringing her hands at the sight of such a humble dish to set before them.

With imperturbable dignity Tysoe did the honours as butler, finding among the few remaining bottles in the cellar a very passable Margaux, and afterwards, replete, Persephone and Thomas Kydd sat in bare chairs by the fire and began to plan.

By his sturdy wardship of the manor, Appleby had earned his place as steward, and his wife was well suited to serve as cook. Lady Kydd would require a maid, of course, and there would be need of others, but these could wait while workmen attended to repairs and furbishing.

Kydd insisted that the land must remain wild for the time being – after all, the manor had first to be made fit for his lady. Furniture, hangings, fitments, stables, horses, a carriage, it was never-ending.

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...