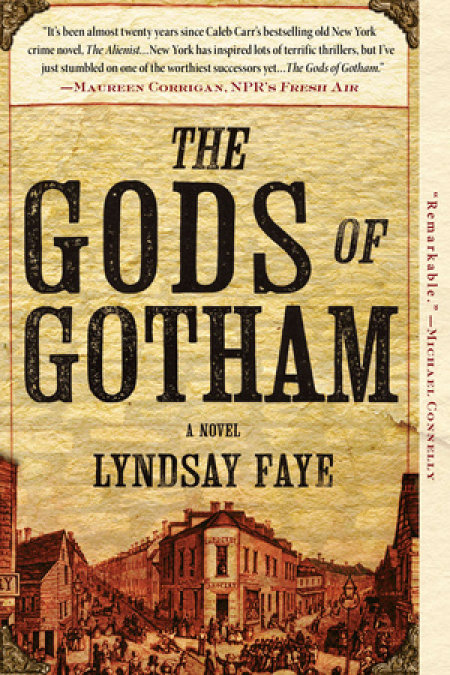

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1845. New York City forms its first police force. The great potato famine hits Ireland. These two seemingly disparate events will change New York City. Forever.

Timothy Wilde tends bar near the Exchange, fantasizing about the day he has enough money to win the girl of his dreams. But when his dreams literally incinerate in a fire devastating downtown Manhattan, he finds himself disfigured, unemployed, and homeless. His older brother obtains Timothy a job in the newly minted NYPD, but he is highly skeptical of this new "police force." And he is less than thrilled that his new beat is the notoriously down-and-out Sixth Ward -- at the border of Five Points, the world's most notorious slum.

One night while making his rounds, Wilde literally runs into a little slip of a girl -- a girl not more than ten years old -- dashing through the dark in her nightshift . . . covered head to toe in blood.

Timothy knows he should take the girl to the House of Refuge, yet he can't bring himself to abandon her. Instead, he takes her home, where she spins wild stories, claiming that dozens of bodies are buried in the forest north of 23rd Street. Timothy isn't sure whether to believe her or not, but, as the truth unfolds, the reluctant copper star finds himself engaged in a battle for justice that nearly costs him his brother, his romantic obsession, and his own life.

Release date: March 15, 2012

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Gods of Gotham

Lyndsay Faye

The

GODS

of

GOTHAM

ALSO BY LYNDSAY FAYE

Dust and Shadow

The

GODS

of

GOTHAM

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For my family,

who taught me that when you are

knocked considerably sideways, you get up and keep going,

or you get up and go in a slightly different direction

In the summer of 1845, following years of passionate political dispute, New York City at long last formed a Police Department.

The potato, a crop that can be trusted to yield reliable nutrition from barren, limited space, had long been the base staple of the Irish tenant farmer. In the spring of 1844, the Gardener’s Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette reported anxiously that an infestation “belonging to the mould tribe” was laying waste to potato crops. There was, the Chronicle told its readers, no definite cause or cure.

These twin events would change the city of New York forever.

SELECTED FLASH TERMINOLOGY*

A

AUTUM. A church.

B

BAT. A prostitute who walks the streets only at night.

BENE. Good; first-rate.

BLOKE. A man.

BURNERS. Rogues who cheat countrymen with false cards or dice.

BUSTLED. Confused; perplexed; puzzled.

BUTTERED. Whipped.

C

CAP. To join in. “I will cap in with him.”

CHAFFEY. Boisterous; happy; jolly.

CHINK. Money.

CRANKY-HUTCH. An insane asylum.

CUPSHOT. Drunk.

D

DEAD RABBIT. A very athletic, rowdy fellow.

DIARY. To remember.

DIMBER. Handsome; pretty.

DUSTY. Dangerous.

E

EASY. Killed.

ERGOTAT. Sick.

ELFEN. Walk light; on tiptoe.

EYE. Nonsense; humbug.

F

FAM GRASP. To shake hands.

FIB. To beat.

FRENCH CREAM. Brandy.

FUNK. To frighten.

G

GINGERLY. Cautiously.

H

HASH. To vomit.

HEMP. To choke.

HEN. A woman.

HICKSAM. A countryman; a fool.

HOCUS. To stupefy.

HUSH. Murder.

I

INSIDER. One who knows.

J

JABBER. To talk in an unknown language.

JACK DANDY. A little impertinent fellow.

K

KEN. A house.

KINCHIN. A young child.

KITTLE. To tickle; to please.

L

LADY BIRD. A kept mistress.

LION. Be saucy; frighten; bluff.

LUSH. Drink.

M

MAB. A harlot.

MAZZARD. The face.

MOLLEY. A miss; an effeminate fellow; a sodomite.

MOUSE. Be quiet; be still.

N

NATURAL. Not fastidious; a liberal, clever fellow.

NED. A ten-dollar gold piece.

NISH. Keep quiet; be still.

NODDLE. An empty-pated fellow.

NOSE. A spy; one who informs.

O

ORGAN. Pipe.

OWLS. Women who walk the street only at night.

P

PALAVER. Talk.

PATE. The head.

PEERY. Suspicious.

PEPPERY. Warm; passionate.

PHYSOG. The face.

PLUMP. Rich; plenty of money.

POGY. Drunk.

Q

QUARRON. A body.

QUASH. To kill; the end of; no more.

QUEER. To puzzle.

R

RABBIT. A rowdy.

RED RAG. The tongue.

S

SANS. Without; nothing.

SLAMKIN. A slovenly female.

SMACK. To swear on the Bible. “The queer cuffin bid me smack the calfskin.”

SQUEAKER. A child.

STAIT. City of New York.

STARGAZERS. Prostitutes.

STOW YOUR WID. Be silent.

SWAG-RUM. Full of wealth.

T

TOGS. Clothes.

TONGUE-PAD. A scold.

U

UPPISH. Testy; quarrelsome.

Y

YIDISHER. A Jew.

* Excerpted from George Washington Matsell, The Secret Language of Crime: Vocabulum, or, The Rogue’s Lexicon (G. W. Matsell & Co., 1859).

THE PILGRIM’S LEGACY

Those daring men, those gentle wives—say, wherefore do they come?

Why rend they all the tender ties of kindred and of home?

’Tis Heaven assigns their noble work, man’s spirit to unbind;—

They come not for themselves alone—they come for all mankind:

And to the empire of the West this glorious boon they bring,

“A Church without a Bishop—a State without a King.”

Then, Prince and Prelate, hope no more to bend them to your sway,

Devotion’s fire inflames their breasts, and freedom points their way,

And in their brave hearts’ estimate, ’twere better not to be,

Than quail beneath a despot, where the soul cannot be free;

And therefore o’er the wintry wave, those exiles come to bring

“A Church without a Bishop—a State without a King.”

• Hymn sung following a lecture at the Tabernacle, New York City, 1843 •

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

When I set down the initial report, sitting at my desk at the Tombs, I wrote:

On the night of August 21, 1845, one of the children escaped.

Of all the sordid trials a New York City policeman faces every day, you wouldn’t expect the one I loathe most to be paperwork. But it is. I get snakes down my spine just thinking about case files.

Police reports are meant to read “X killed Y by means of Z.” But facts without motives, without the story, are just road signs with all the letters worn off. Meaningless as blank tombstones. And I can’t bear reducing lives to the lowest of their statistics. Case notes give me the same parched-headed feeling I get after a night of badly made New England rum. There’s no room in the dry march of data to tell why people did bestial things—love or loathing, defense or greed. Or God, in this particular case, though I don’t suppose God was much pleased by it.

If He was watching. I was watching, and it didn’t please me any too keenly.

For instance, look what happens when I try to write an event from my childhood the way I’m required to write police reports:

In October 1826, in the hamlet of Greenwich Village, a fire broke out in a stable flush adjacent to the home of Timothy Wilde, his elder brother, Valentine Wilde, and his parents, Henry and Sarah; though the blaze started small, both of the adults were killed when the conflagration spread to the main house by means of a kerosene explosion.

I’m Timothy Wilde, and I’ll say right off, that tells you nothing. Nix. I’ve drawn pictures with charcoal all my life to busy my fingers, loosen the feeling of taut cord wrapped round my chest. A single sheet of butcher paper showing a gutted cottage with its blackened bones sticking out would tell you more than that sentence does.

But I’m getting better used to documenting crimes now that I wear the badge of a star police. And there are so many casualties in our local wars over God. I grant there must have been a time long ago when to call yourself a Catholic meant your bootprint was stamped on Protestant necks, but the passage of hundreds of years and a wide, wide ocean ought to have drowned that grudge between us, if anything could. Instead here I sit, penning a bloodbath. All those children, and not only the children, but grown Irish and Americans and anyone ill-starred enough to be caught in the middle, and I only hope that writing it might go a way toward being a fit memorial. When I’ve spent enough ink, the sharp scratch of the specifics in my head will dull a little, I’m hoping. I’d assumed that the dry wooden smell of October, the shrewd way the wind twines into my coat sleeves now, would have begun erasing the nightmare of August by this time.

I was wrong. But I’ve been wrong about worse.

Here’s how it began, now that I know the girl in question better and can write as a man instead of a copper star:

On the night of August 21, 1845, one of the children escaped.

The little girl was aged ten, sixty-two pounds, dressed in a delicate white shift with a single row of lace along the wide, finely stitched collar. Her dark auburn curls were pulled into a loose knot at the top of her head. The breeze through the open casement felt hot where her nightdress slipped from one shoulder and her bare feet touched the hardwood. She suddenly wondered if there could be a spyhole in her bedroom wall. None of the boys or girls had ever yet found one, but it was the sort of thing they would do. And that night, every pocket of air seemed breath on flesh, slowing her movements to sluggish, watery starts.

She exited through the window of her room by tying three stolen ladies’ stockings together and fixing the end to the lowest catch on the iron shutter. Standing up, she pulled her nightgown away from her body. It was wet through to her skin, and the clinging fabric made her flesh crawl. When she’d stepped blindly out the window clutching the hose, the August air bloated and pulsing, she slid down the makeshift rope before dropping to an empty beer barrel.

The child quit Greene Street by way of Prince before facing the wild river of Broadway, dressed for her bedroom and hugging the shadows like a lifeline. Everything blurs on Broadway at ten o’clock at night. She braved a flash torrent of watered silk. Glib-eyed men in double vests of black velvet stampeded into saloons cloaked from floor to ceiling in mirrors. Stevedores, politicians, merchants, a group of newsboys with unlit cigars tucked in their rosy lips. A thousand floating pairs of vigilant eyes. A thousand ways to be caught. And the sun had fallen, so the frail sisterhood haunted every corner: chalk-bosomed whores desperately pale beneath the rouge, their huddles of five and six determined by brothel kinships and by who wore diamonds and who could only afford cracked and yellowing paste copies.

The little girl could spot out even the richest and healthiest of the street bats for what they really were. She knew the mabs from the ladies instantly.

When she spied a gap in the buttery hacks and carriages, she darted like a moth out of the shadows. Willing herself invisible, winging across the huge thoroughfare eastward. Her naked feet met the slick, tarry waste that curdled up higher than the cobbles, and she nearly stumbled on a gnawed ear of corn.

Her heart leaped, a single jolt of panic. She’d fall—they’d see her and it would all be over.

Did they kill the other kinchin slow or quick?

But she didn’t fall. The carriage lights veering off scores of plate-glass windows were behind her, and she was flying again. A few girlish gasps and one yell of alarm marked her trail.

Nobody chased her. But that was nobody’s fault, really, not in a city of this size. It was only the callousness of four hundred thousand people, blending into a single blue-black pool of unconcern. That’s what we copper stars are for, I think … to be the few who stop and look.

She said later that she was seeing in badly done paintings—everything crude and two-dimensional, the brick buildings dripping watercolor edges. I’ve suffered that state myself, the not-being-there. She recollects a rat gnawing at a piece of oxtail on the pavement, then nothing. Stars in a midsummer sky. The light clatter of the New York and Harlem train whirring by on iron railway tracks, the coats of its two overheated horses wet and oily in the gaslight. A passenger in a stovepipe hat staring back blankly the way they’d come, trailing his watch over the window ledge with his fingertips. The door open on a sawdusty slaughter shop, as they’re called, half-finished cabinetry and dismembered chairs pouring into the street, as scattered as her thoughts.

Then another length of clotted silence, seeing nothing. She reluctantly pulled the stiffening cloth away from her skin once more.

The girl veered onto Walker Street, passing a group of dandies with curled and gleaming soaplocks framing their monocles, fresh and vigorous after a session with the marble baths of Stoppani’s. They thought little enough of her, though, because of course she was running hell for leather into the cesspit of the Sixth Ward, and so naturally she must have belonged there.

She looked Irish, after all. She was Irish. What sane man would worry over an Irish girl flying home?

Well, I would.

I lend considerably more of my brain to vagrant children. I’m much closer to the question. First, I’ve been one, or near enough to it. Second, star police are meant to capture the bony, grime-cheeked kinchin when we can. Corral them like cattle, then pack them in a locked wagon rumbling up Broadway to the House of Refuge. The urchins are lower in our society than the Jersey cows, though, and herding is easier on livestock than on stray humans. Children stare back with something too hot to be malice, something helpless yet fiery when police corner them … something I recognize. And so I will never, not under any circumstances, never will I do such a thing. Not if my job depended on it. Not if my life did. Not if my brother’s life did.

I wasn’t musing over stray kids the night of August twenty-first, though. I was crossing Elizabeth Street, posture about as stalwart as a bag of sand. Half an hour before, I’d taken my copper star off in disgust and thrown it against a wall. By that point, however, it was shoved in my pocket, digging painfully into my fingers along with my house key, and I was cursing my brother’s name in a soothing inner prayer. Feeling angry is far and away easier for me than feeling lost.

God damn Valentine Wilde, I was repeating, and God damn every bright idea in his goddamned head.

Then the girl slammed into me unseeing, aimless as a torn piece of paper on the wind.

I caught her by the arms. Her dry, flitting eyes shone out pale grey even in the smoke-sullied moonlight, like shards of a gargoyle’s wing knocked from a church tower. She had an unforgettable face, square as a picture frame, with somber swollen lips and a perfect snub nose. There was a splash of faint freckles across the tops of her shoulders, and she lacked height for a ten-year-old, though she carried herself so fluid that she can seem taller in memory than in person.

But the only thing I noticed clearly when she stumbled to a halt against my legs as I stood in front of my house that night was how very thoroughly she was covered in blood.

ONE

To the first of June, seven thousand emigrants had arrived … and the government agent there had received notice that 55,000 had contracted for passage during the season, and nearly all from Ireland. The number expected to come to Canada and the States is estimated by some as high as 100,000. The rest of Europe will probably send to the States 75,000 more.

• New York Herald, summer 1845 •

Becoming a policeman of the Sixth Ward of the city of New York was an unwelcome surprise to me.

It’s not the work I imagined myself doing at twenty-seven, but then again I’d bet all the other police would tell it the same, since three months ago this job didn’t exist. We’re a new-hatched operation. I suppose I’d better say first how I came to need employment, three months back, in the summer of 1845, though it’s a pretty hard push to talk about that. The memory fights for top billing as my ugliest. I’ll do my best.

On July eighteenth, I was tending bar at Nick’s Oyster Cellar, as I’d done since I was all of seventeen years old. The squared-off beam of light coming through the door at the top of the steps was searing the dirt into the planked floor. I like July, the way its particular blue had spread over the world when I’d worked on a ferryboat to Staten Island at age twelve, for instance, head back and mouth full of fresh salt breeze. But 1845 was a bad summer. The air was yeasty and wet as a bread oven by eleven in the morning, and you could taste the smell of it at the back of your throat. I was fighting not to notice the mix of fever sweat and the deceased cart horse half pushed into the alley round the corner, as the beast seemed by degrees to be getting deader. There are meant to be garbage collectors in New York, but they’re a myth. My copy of the Herald lay open, already read back to front as is my morning habit, smugly announcing that the mercury was at ninety-six and several more laborers had unfortunately died of heatstroke. It was all steadily ruining my opinion of July. I couldn’t afford to let my mood sour, though. Not on that day.

Mercy Underhill, I was sure of it, was about to visit my bar. She hadn’t done so for four days, and in our unspoken pattern that was a record, and I needed to talk to her. Or at least try. I’d recently decided that adoring her was no longer going to stand in my way.

Nick’s was laid out in the usual fashion for such places, and I loved its perfect typicalness: a very long stretch of bar, wide enough for the pewter oyster platters and the dozens of beer tumblers and the glasses of whiskey or gin. Dim as a cave, being half underground. But on mornings like that one the sun cut through wonderfully, so we didn’t yet need the yellow-papered oil lamps that sent friendly smoke marks up the plaster. No furniture, just a series of booths with bare benches lining the walls, curtained if you wanted although no one ever closed them. Nick’s wasn’t a place for secrets. It was a forum for the frantic young bulls and bears to scream things across the room after a twelve-hour stint at the Exchange, while I listened.

I stood pouring off a gallon of whiskey for a ginger boy I didn’t recognize. The East River’s bank swarms with rickety foreign creatures trying to shake off their sea legs, and Nick’s was on New Street, very close to the water. The lad waited with his head tilted and his little claws on the cedar bar plank. He stood like a sparrow. Too tall to be eight years old, too scared to be ten. Hollow-boned, eyes glassily seeking free scraps.

“This for your parents?” I wiped my fingers on my apron, corking the earthenware jug.

“For Da.” He shrugged.

“Twenty-eight cents.”

His hand came out of his pocket with a ragtag assortment of currency.

“Two shillings makes two bits, so I’ll take that pair and wish you welcome. I’m Timothy Wilde. I don’t pour shallow, and I don’t water the merchandise.”

“Thankee,” he said, reaching for the jug.

There were dark treacle stains at the underarms of his tattered shirt due to the last molasses barrel he’d gammed from being too high, I saw next. So my latest customer was a sugar thief. Interesting.

That’s a typical saloon keeper’s trick: I notice a great many things about people. A fine city barman I’d be if I couldn’t spot the difference between a Sligo dock rat with a career in contraband molasses and the local alderman’s son asking after the same jug of spirits. Barmen are considerably better paid when they’re sharp, and I was saving all the coin I could lay hands on. For something too crucial to even be called important.

“I’d change professions, if I were you.”

The bright black sparrow’s eyes turned to slits.

“Molasses sales,” I explained. “When the product isn’t yours, locals take exception.” One of his elbows shifted, growing more fluttery by the second. “You’ve a ladle, I suppose, and sneak from the market casks when their owners are making change? All right, just quit the syrups and talk to the newsboys. They make a good wage too, and don’t catch beatings when the molasses sellers have learned their sly little faces.”

The boy ran off with a nod like a spasm, clutching the sweating jug under his wing. He left me feeling pretty wise, and neighborly to boot.

“It’s useless to counsel these creatures,” Hopstill intoned from the end of the bar, sipping his morning cup of gin. “He’d have been better off drowned on the way over.”

Hopstill is a London man by birth, and not very republican. His face is equine and drooping, his cheeks vaguely yellow. That’s due to the brimstone for the fireworks. He works as a lightning-maker, sealed away in a garret creating pretty explosions for theatricals at Niblo’s Gardens. Doesn’t care for children, Hopstill. I don’t mind them a bit, admiring candor the way I do. Hopstill doesn’t care for Irish folk either. That’s common enough practice, though. It doesn’t seem sporting to me, blaming the Irish for eagerly taking the lowest, filthiest work when the lowest, filthiest work is all they’re ever offered, but then fairness isn’t high on the list of our city’s priorities. And the lowest, filthiest work is getting pretty hard to come by these days, as the main of it’s already been snapped up by their kin.

“You read the Herald,” I said, fighting not to be annoyed. “Forty thousands of emigrants since last January and you want them all to join the light-fingered gentry? Advising them is only common sense. I’d sooner work than steal, myself, but sooner steal than starve.”

“A fool’s exercise,” Hopstill scoffed, pushing his palm through the sheaves of grey straw that pass for his hair. “You read the Herald. That rank patch of mud is on the brink of civil war. And now I hear tell from London that their potatoes have started rotting. Did you hear about that? Just rotting, blighted as a plague of ancient Egypt. Not that anyone’s surprised. You won’t catch me associating with a race that’s so thoroughly called down the wrath of God.”

I blinked. But then, I had often been shocked by the sage opinions bar guests had gifted me regarding the members of the Catholic church, the only breathing examples they’d ever seen being the Irish variety. Bar guests who were otherwise—for all appearances—perfectly sane. First thing the priests do with the novice nuns is sodomize them, and the priests as do thoroughest work rise up the ranks, that’s the system—they aren’t even fully ordained until their first rape is done with. Why, Tim, I thought you savvied the pope lived off the flesh of aborted fetuses; it’s common enough knowledge. I said no way in hell, is what, the very idea of letting an Irish take the extra room, what with the devils they summon for their rituals, would that be right with little Jem in the house? Popery is widely considered to be a sick corruption of Christianity ruled by the Antichrist, the spread of which will quash the Second Coming like an ant. I don’t bother responding to this brand of insanity for two reasons: idiots treasure their facts like newborns, and the entire topic makes my shoulders ache. Anyhow, I’m unlikely to turn the tide. Americans have been feeling this way about foreigners since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798.

Hopstill misread my silence as agreement. He nodded, sipping his spirits. “These beggars shall steal whatever isn’t nailed down once they arrive here. We may as well save our breath.”

It went without saying that they would arrive. I walk along the docks edging South Street only two blocks distant on my way home from Nick’s pretty often, and they boast ships thick as the mice, carrying passengers plentiful as the fleas. They have done for years—even during the Panic, when I’d watched men starve. There’s work to be had again now, railways to lay and warehouses to be built. But whether you pity the emigrants or rant about drowning them, on one subject every single citizen is in lockstep agreement: there’s an unholy tremendous amount of them. A great many Irish, and all of those Catholics. And nearly everyone concurs with the sentiment that follows after: we haven’t the means nor the desire to feed them all. If it gets any worse, the city fathers will have to pry open their wallets and start a greeting system—some way to keep foreigners from huddling in waterfront alleys, begging crusts from the pickpockets until they learn how to lift a purse. The week before, I’d passed a ship actively vomiting up seventy or eighty skeletal creatures from the Emerald Isle, the emigrants staring glassy-eyed at the metropolis as if it were a physical impossibility.

“That’s none too charitable, is it, Hops?” I observed.

“Charity has nothing to do with it.” He scowled, landing his cup on the counter with a dull ping. “Or rather, this particular metropolis will have nothing to do with charity in cases where charity is a waste of time. I should sooner teach a pig morals than an Irishman. And I’ll take a plate of oysters.”

I called out an order for a dozen with pepper to Julius, the young black fellow who scrubbed and cracked the shells. Hopstill is a menace to cheerful thought. It was hovering on the tip of my tongue to mention this to him. But just then, a dark gap cut into the spear of light arrowing down the stairs and Mercy Underhill walked into my place of employment.

“Good morning, Mr. Hopstill,” she called in her tender little chant. “And Mr. Wilde.”

If Mercy Underhill were any more perfect, it would take a long day’s work to fall in love with her. But she has exactly enough faults to make it ridiculously easy. A cleft like a split peach divides her chin, for instance, and her blue eyes are set pretty wide, giving her an uncomprehending look when she’s taking in your conversation. There isn’t an uncomprehending thought in her head, however, which is another feature some men would find a fault. Mercy is downright bookish, pale as a quill feather, raised entirely on texts and arguments by the Reverend Thomas Underhill, and the men who notice she’s beautiful have the devil’s own time of it coaxing her face out of whatever’s latest from Harper Brothers Publishing.

We try our best, though.

“I require two pints … two? Yes, I think that ought to do it. Of New England rum, please, Mr. Wilde,” she requested. “What were you talking of?”

She hadn’t any vessel, only her open wicker basket with flour and herbs and the usual hastily penned scraps of half-finished poetry keeking out, so I pulled a rippled glass jar from a shelf. “Hopstill was proving that New York at large is about as charitable as a coffin vendor in a plague town.”

“Rum,” Hopstill announced sourly. “I didn’t take either you or the reverend for rum imbibers.”

Mercy smoothed back a lock of her sleek but continually escaping black hair as she absorbed this remark. Her bottom lip rests just behind her top lip, and she tucks the bottom one in slightly when she’s ruminating. She did then.

“Did you know, Mr. Wilde,” she inquired, “that elixir proprietatis is the only medicine that can offer immediate relief when dysentery threatens? I pulverize saffron with myrrh and aloe and then suffer the concoction to stand a fortnight in the hot sun mixed with New England rum.”

Mercy passed me a quantity of dimes. It was still good to see so many disks of metal money clinking around again. Coins vanished completely during the Panic, replaced by receipts for restaurant meals and tickets for coffee. A man could hew granite for ten hours and get paid in milk and Jamaica Beach clams.

“That’ll teach you to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...