December 1, 1955

Montgomery, Alabama

“Gal, get those coins in that slot or you ain’t going nowhere.”

The driver on that first bus I’d incorrectly hopped on in my flustered state had fussed that at me. Now, here I was again. Fumbling. Hoping the driver on this right bus didn’t flare up with the same kinds of indignities.

Head held low, I tried putting those coins in, hoping other riders couldn’t see my face. Unlike the coins I kept fumbling with, my tears were pooled in place, unfallen as of yet. We had an agreement. Tears could flow all they wanted once I was safely situated back in the Colored section. Not until then. And definitely not in front of some impatient individual responsible for driving me to freedom.

Mattie Banks, get yourself together!

Plopping my suitcase at my feet, I had the good sense to wipe my sweaty fingers on my skirt first. Scooping up fallen coins, I managed to get the first nickel in. But that second one felt the need to make a fool of me. I couldn’t do nothing except watch it slip from my shaky grip and roll backwards down the steps into the evening, as if escaping this uncertain journey.

That set the driver off.

He was fussing, close to cussing and calling me everything except a child of God and a nasty kitchen sink when the passenger waiting to board behind me intervened.

“Ma’am…”

Not that I knew every Colored person in Montgomery, but he was an older, unfamiliar gentleman. He hadn’t been at the bus stop a moment ago when I was praying for another way to handle this predicament. Maybe he was the heaven-sent angel I needed?

Watching him mount the bus steps, I had enough sense not to correct Mister Angel Man about my not being a “ma’am.” I was sixteen, but from the back he wouldn’t have known that. I’d had what Mama called “womanish hips” since turning thirteen. Courtesy of my situation, they’d soon be on their way to further spreading.

Thanking him and standing aside, I watched Mister Angel Man deposit my rebellious nickel and his own fare before tipping his hat and descending the front steps. Grabbing my suitcase, I followed him to the rear, hoping the annoyed driver wouldn’t take off just to prove a point, like some did, taking my precious ten cents with him.

I hate this double-entrance dance.

Drop your fare up front.

Hop off the bus.

Hightail it to the rear and board at the back like a less-than citizen.

It was a belittling ballet played to the melody of racism.

My great-granny’s days of slavery were finished, but that didn’t keep these White folks around here from using every opportunity to make themselves feel first-and-foremost. As if the rest of God’s creation was insignificant, or an absent-minded afterthought. But right then, I couldn’t spend time on White folks’ foolery. Not with my own world laying heavy on me.

A true gentleman, my angel mister let me board that Cleveland Avenue-bound bus ahead of him. Good thing he did, seeing as how the Colored section was crowded with laborers and day workers who, unlike Mama and me, weren’t live-ins. I didn’t feel like talking, but I was raised better than to not say hello to those I knew. Last thing I needed was Mama hearing about me acting grown when I already had enough grown trouble of my own.

Trying to look normal and unsuspicious, I offered quick greetings to folks I recognized before claiming the last available window seat and breathing a sigh of relief that my nickel-fumbling hadn’t earned me too much attention. No one stopped me, asked what I was doing on the bus that time of evening, or where I was going. That had me feeling like I’d won something. But my sense of winning disappeared the moment I sat and plopped that small suitcase on my lap.

Ain’t easy feeling victorious when you’re running from the first sin to the second.

I would have preferred being at the hand-me-down desk in the room Mama and I shared, listening to our tiny transistor radio and tussling with math problems, or getting gloriously lost in English Lit. Or aiding Mama with the evening meal for the Stantons. Setting dishes. Laying out linens. Taste-testing her mashed potatoes and gravy—the potatoes were always creamy, smooth perfection. Helping her serve then heading over to Sadie’s. Instead, I was shrinking in that seat clutching a suitcase as if it was my lifeline to a better time.

Truth was, I was lost. Desperate.

Womanish hips didn’t make me more than a scared sixteen-year-old Colored girl without options.

Sadie said it won’t take but a few minutes.

Good sense should’ve had me running in the opposite direction, but I was in no position to ignore help and decided to credit Sadie with knowing something I didn’t. Sadie James and I had been thick as thieves since my moving to Montgomery when I was three. Like sisters, we fell out regularly but couldn’t stay mad at each other on account of I was Mama’s only child, and Sadie was her parents’ youngest, and only daughter. We needed each other. What I didn’t need was Sadie’s occasional superiority. That high-yellow girl with pretty hazel eyes acted as if having four big brothers, a librarian for a mother, and a dentist for a father helped her know things, made her an authority on life despite being sixteen right along with me. Nine times out of ten, Sadie’s “knowing” was as reliable as a milk pail with no bottom. But like I said, I was desperate.

Lord, please let me live to regret it.

I’d rather live with a broken heart than bleed to death out there on the edge of town after Miss Celestine finished between my legs.

“I’ll come with you, Mattie, if you want me to.”

Lord knows I’d wanted to take Sadie up on that offer. Instead, I faked being braver than I was, telling her to stay at her house—where I should’ve been, working on a school project—in case Mama called.

“I’m not nobody’s actress, Mattie! What if Miss Dorothy does?”

“Answer the damn phone like normal, Sadie, and tell Mama I’m in the bathroom! Or something. Just make it sound legitimate.”

I knew better than fibbing or saying “damn” like some foul-mouthed man, but I was terrified.

Lord, please don’t add dishonesty and profanity to my growing list of sins.

Staring out the bus window, I suddenly wished I was Catholic, not Baptist. Wished I had one of those long pretty rosaries. Some tangible comfort to occupy myself with while praying to the gracious mother of our savior, begging her atonement for the iniquity I was about to commit, and those I’d already transacted. She’d understand. The virgin was a woman and knew something about limitations and predicaments.

Having no such pretty beads, I fiddled with the handle of the suitcase Miz Stanton no longer needed. Mama’s employer had given it to me despite the fact that she didn’t pay my mother wanderlust money. The best we could come up with was heading to Louisiana each summer visiting relatives while the Stantons vacationed all over God’s glorious earth—bringing home marvelous memories and trinkets for Mama and me to relish, envy.

Watching the streets of Montgomery pass by I wondered what privilege felt like. Privilege might’ve given me another way, an opportunity.

Dear Lord, I promise Sadie and I tried all kinds of scenarios. This is the only one that makes sense, and the best we could come up with. I repent for not knowing something different.

The tail end of that prayer wasn’t for God but for me, or rather what I was hiding behind that second-hand suitcase pressed against my midsection. That suitcase was small enough to fit underneath the seat, but I needed it right then more than it needed me.

“Little Miss…”

I knew the voice without looking. It was the guardian angel of my runaway nickel. I’d been so busy staring out the window wishing up another way, that I didn’t notice him taking the seat beside me. I had to blink away tears just to see him clearly.

His voice was quiet. Calm. He had a kind face with a fascinating birthmark, sort of like a pollywog swimming near his left ear. “Here. Use this.”

I wanted to decline the spotless handkerchief his wife must’ve pressed. But it was either that or wipe my sleeve across my face like a little kid. Lord knew I wasn’t that. “Thank you.”

His response was a gentle smile that made me wish my daddy wasn’t dead.

Vacating his seat as the bus eased to the curb, he faced forward, as if I deserved to cry with dignity, without anyone looking.

Guess the little boy across the aisle didn’t see it that way. He was so busy staring, I figured I’d smeared snot across my face.

Turning the hankie over, I made good use of it, catching a hint of lavender water similar to what Mama used when ironing. Tidying myself, I realized Mister Angel Man hadn’t solely left to grant me privacy, but because the Colored section was at capacity.

He wasn’t the only man standing. Others had joined him in the aisle allowing the ladies now boarding in the back to sit in their places. A woman, smelling delicious, like fresh fried chicken, and wearing a domestic uniform plopped her weary-looking self beside me—a stained apron draped over her purse, and ugly-sensible shoes on her feet. Obviously, she did the same kind of work Mama did, but without being a live-in.

Giving her a polite semi-smile, I resumed window-gazing as if answers to my problems lived outside. Suddenly, that window was a barrier keeping solutions at a foggy distance. Or perhaps that was my warm breath distorting the glass with hazy illusions. Had me feeling that if I could break that window and reach creation my answers could get free.

I don’t know.

I was tired. Scared. My thinking wasn’t clear. I hadn’t eaten since breakfast and what little I’d managed to swallow came back up into the commode. Being seated next to someone smelling of fried food suddenly wasn’t working out too well, had me afraid I’d upchuck emptiness and fear. I thought to excuse myself and stand with the men, wiggle myself near the back door so I could get fresh air whenever it opened. But my seat partner’s sudden hissing interrupted that plan.

“Jesus, what now? I’m just tryna get home.”

Her words were weighted with something besides fatigue. I looked away from the window to see her weary expression had slid into a mishmash of exasperation and heightened caution. That had me following her tight gaze towards the front of the bus where the driver was raising sand. So caught up in private misery, I’d been unmindful of external happenings and the fact that we were idling curbside. Might’ve been there a minute or a long moment; only now was I refocused, noticing how the Reserved section at the front of the bus was as packed as the back.

“Reserved” was Montgomery’s sugar-coated way of saying “Whites Only.”

Water fountains. Restrooms. Diners. Libraries. The first-floor seats at the movies. If it was meant for public gatherings or consumption, race markers were posted reminding us of who was and wasn’t welcome.

Neighborhoods didn’t need signs. It wasn’t just near about impossible to live on their side; we knew better than to try. You’d wind up with a fiery cross in your yard or a firebomb in your front room. Forget living. Some parts of town you’d better not show your brown face after sundown. Not if you wanted to see sunrise.

As for worship, I wasn’t sure if we loved the same God, but clearly even heaven thought it best for Negroes and Whites to have their own sanctuaries come Sundays. Maybe it was because us Baptists and Pentecostals required more time and space for shouting and demonstrating? Then again, our African Methodist Episcopalians and Black Presbyterians, like Sadie’s family, were dignified, restrained, used hymnals, and got out of church long before we did. Still, the Lord didn’t open those White-church doors in welcome to even them. Truth be told? Didn’t bother me that He didn’t. I liked a White-free world two hours every Sabbath.

Even when reserved and only signs weren’t posted or present, we knew. We only had to see or smell the shabby, unkempt condition of whatever it was to know it was meant for us, not them. It made me wonder if the first lessons a Negro child learned were A-B-C, 1-2-3, and separate and unequal living. The times one of us dared to eat or drink from a place not designated Colored? You best know there were repercussions. A ticket. White backlash. A handcuffed trip to the courthouse. A sentence of a fine or jail time. Or, depending on the severity of the offense and how “Christian” White folks and the law were or weren’t feeling, we could wind up peculiar fruit swinging lifeless from trees like Miss Billie sang. Bottom line: we knew where not to be. Including up front in the Reserved section.

Case in point right then: riders were being ordered to make it light on themselves and give up needed seats. From what I could see, none of us were past that privilege line. So why was the agitated driver, giving those four riders the “what for” and acting indignant?

“Lord, these crackers. Don’t make no sense all four of them gotta give up their seats ’cause one White man’s standing.” My riding partner sucked her teeth, punctuating her whispered sentiment with disgust.

That disgust didn’t interrupt my focus. I was fixed on the folks up front.

Three of those riders were taking their time moving, yet complying. Their added bodies made matters difficult, but Colored folks already filling the jam-packed aisle shifted, miraculously making room for them. All except that one woman. She still sat, not moving fast enough. Or rather, not at all.

I couldn’t see her face, only the back of her head with its dainty hat, but the lady wasn’t vacating her seat as the driver demanded. She stayed fixed like it was a good night for sitting. Or maybe rebellion?

She wasn’t in the wrong, as far as I could see. Wasn’t she in the Colored section, in an aisle seat directly behind the Reserved line? She should’ve been left alone—wasn’t bothering nobody, or violating nothing. But we all knew how this thing worked. If White folks wanted it, we had to give it, even if the thing in question was ours and they had no right to it. What we didn’t give got taken. Sometimes with, sometimes without our resistance. From my vantage point, it looked like that lady had decided a tussle was her preference. Funny thing was, she wasn’t loud or uncouth, like Mama liked to say. That lady simply sat in her seat, letting her stillness do her warring.

“I ain’t telling you again. You getting up like I said?” That driver was some kind of mad.

When she declined and he threatened her with arrest, that lady said something I couldn’t hear, but wished I had.

I didn’t know, didn’t care what the White folks up front were feeling. Back where I was? There was a whole mess of tension. Like some humongous, slithering snake had wrapped us Colored folks in its coil. Multiple feelings were probably mixed up in it, but clearly there was concern. Unease. Some impatience. And a lot of masked anger floating like steam clouds off our men. All of that made me uncomfortable until, suddenly, I’d had enough of whatever was going on. No, I didn’t think the lady should have to move but I wanted her to. Anything to stop that venomous concoction boiling in the back and get that driver in his seat and get me where I was going. But he didn’t sit down. That red-faced man stomped off the bus into the evening going only God knew where and escalating this thing.

“Miz Rosa, you ain’t moving?”

I don’t know who hissed it, but somebody did. That lady turning her head sideways was the only indication she’d heard them.

Seeing her profile, she felt familiar. Kind of resembled that lady who’d stopped Mama in the store, handing her a flier for some Colored folks’ meeting the other day. Whoever she was, she seemed calm, like a warrior who might’ve known the war was stacked against her but was devoted to the bitter end. And bitter it got when that driver returned madder than ten wet hens. Not long after, two officers of the law joined him—their appearance on that bus halting whatever whispering or worrying might’ve been in progress.

Watching those police approaching that woman I felt the kind of nervous fear that keeps you from moving. All I could do was squeeze my suitcase and pray nothing horrible happened.

Horrible happened. And fast.

When those officers confronted that lady, Miz Rosa, questioning whether or not the driver had asked her to move and she confirmed he had, I held my breath. Her telling those policemen to their faces how she didn’t feel she should have to stand had my whole world suspended and just about flipped on its head.

That soft-spoken, gentle-looking lady was standing up for herself like that?

I couldn’t say if she had crazy courage or was plain zany. Maybe the situation called for a little bit of both? Or could be she was simply fatigued at the end of a work day, or was tired of giving up things she deserved as if they’d never been hers? Whatever the case, face pressed to the window, I couldn’t crane my neck enough to see what was going on after those officers escorted her from the bus. But I wanted to. Like my seeing could help keep her safe from something worse occurring. Or as if by keeping my eyes on her I could soak up some of whatever it was that let her say enough is enough, I ain’t moving today.

What directly transpired after that I don’t recall. Thoughts were too busy rolling through my mind like wrecking balls, hitting barriers, knocking down walls. Riding that bus as it pulled away, I wondered what life would feel like defying rules and making my own decisions. The mere idea had something turning inside of me, deep in my core. Deeper than my belly. Kinda like a flame on a matchstick, dying and breathing its last only for someone to blow and spark its life again. Not some blaze running amuck across a cane field. Just a gentle flame safely contained in the palm of your hand.

“This ain’t nothing but those two other gals all over again.”

Expecting my former seat partner, I was surprised to see a different, much older woman seated next to me speaking so softly I had to lean in to hear. Again, I’d been caught by my thoughts and hadn’t noticed the changes at the back of the bus. Who’d gotten on. Who’d gotten off.

“You heard about what happened to those two, didn’t you?” She named the two girls who’d, not long before, tried the same kind of resisting on Montgomery’s bus line.

My whisper matched hers. “Yes, ma’am.”

“Hmph! They was about your age, trying something sort of like what Rosa just pulled.” She laughed a dry, husky laugh. “I’d expect y’all’s generation to be up to some tomfoolery. But this?” Shaking her head, she laughed that dry-as-summertime laugh again, but with something sounding like pride mixed in. “Can’t say I blame her. I credit her for doing what she did. We gets tired of being the ones always giving. Dying. Just August they took that little Emmett and did awful things to him like he didn’t belong to nobody.” She shivered at the cruelty inflicted on a boy from Chicago, younger than me, who was brutally murdered while visiting relatives down in Mississippi. We sat saying nothing, until she continued, voice brightening. “Lord, I’d love to be a fly on the wall when ol’ Parks learns what his sweet wife done.”

“Yes, ma’am.” My thoughts were so hooked on what had just happened that my response sounded flat.

Colored folks’ pushing back wasn’t a new notion to me. We might’ve been subtle with it most days. That didn’t mean we didn’t find ways to thumb our noses at Jim Crow living. Now, Miz Rosa’s actions? I couldn’t put a finger on it, but something about what I’d witnessed felt drastic. Frighteningly heroic. Like maybe I’d been privy to change in the making.

Thinking on Miz Rosa, I forgot about myself and what I was running to or from. When I finally refocused, that bus was nearly empty and just about to head back the way we’d come.

“Oh, Lord…”

Thankfully, I signaled my need to get off in time enough for my stop. With a mess of anxiousness piling up in my throat, I just about tumbled outdoors into that December evening with nothing but my suitcase and uncertainty keeping me company.

Which way is it?

“Look for that split tree standing all by itself next to that sunflower field. That narrow road running alongside it takes you all the way to her place.”

That was the best Sadie could do seeing as how Miss Celestine didn’t have a proper address living way out here off of the back end of Hayneville Road in what my Louisiana family would’ve called “The Cut-Off” with all its shot houses, or speakeasies, and other less than suitable establishments. Besides questionable businesses, wasn’t much else around here but fields. A creek. A grove of trees that, in the descending dark, seemed close to creepy.

I didn’t scare easily. My acting, in Mama’s words, too bold was partly to blame for my being out there alone looking for Miss Celestine’s. Being bold at home was one thing. Walking a dirt road in the semi-dark made me wish I was somebody’s innocent lap baby snuggled safely. But I wasn’t an infant. And far from innocent.

I didn’t mean to touch Edward… or let him touch me.

I hadn’t meant to do half the things we’d done until I was good, grown, and married. But I did. He did. Now, we had things to fix. Rather, I was taking it upon myself to handle the fixing.

Edward doesn’t need to know my business.

That’s why I was out there surrounded by high grass and weeds, clutching a suitcase, and keeping an eye out for critters and snakes instead of studying at Sadie’s. Not only was I too bold, I was too nosey. Thank God. Otherwise, last night, I might’ve missed overhearing Doctor and Miz Stanton discussing Edward’s coming home from college for Christmas break this weekend. Three whole weeks early, because of a broken leg! I’d needed every one of those weeks to figure out what to do about my monthly flow disappearing.

“Dearest, he’ll handle getting back and forth to class on crutches. If that proves tedious, the infirmary made a wheelchair available. Edward’ll manage fine until Christmas vacation.”

I couldn’t have agreed more with Doc Stanton.

Leave it to Miz Stanton to object. True southern belle, she couldn’t tolerate the idea of her precious boy experiencing the slightest discomfort. His sister Abigail was two years younger, making Edward the oldest chronologically, but he was definitely his mama’s baby.

“Baby…”

For the first time, I allowed that word to slip across my lips, whispering as if afraid of its power, portent. I also knew it would be the last utterance when I saw the shadowy outline of a small house in the distance. The sight of it left me shivering.

Sadie said Miss Celestine won’t hurt me.

Soothing my mind with that yet-to-be-proven fact, I paused in the middle of a weed-infested path to consider the split tree that looked like it should’ve fallen long ago but was somehow standing. It was wider, taller up close than it appeared from the roadway. Some folks said God meant to lightning-strike Miss Celestine for dancing naked in the rain but had mercy at the last second and struck that tree instead. Others said the tree broke down the middle and bled with the weight of too many Colored bodies lynched from its limbs. Whichever was true, that split and twisted-looking tree might as well have been one of the white-gloved ushers at church ordering me along as if I had no say and couldn’t choose an alternate direction.

A small creek ran alongside the path like Sadie said. Should’ve been some comfort in seeing that child knew what she was talking about for once, but it wasn’t. The farther up that path I went, the less human I felt.

“She’s gentle. Efficient.” Quoting Sadie James while crossing a rickety footbridge, I knew I was desperate to be following my best friend’s advice when she’d barely even kissed a boy. What did she know about this kind of business?

According to Sadie, she’d not only overhead her brothers discussing such things, but her cousin Brenda Lee had a friend who knew a girl who’d needed Miss Celestine.

“Brenda Lee told me her friend told her that girl said Miss Celestine burns sage and lights candles and calls on the ancestors before doing her business. She packs your lady parts with healing herbs afterwards, and lets you rest a while. Then you leave. Like nothing happened.”

No hospit. . .

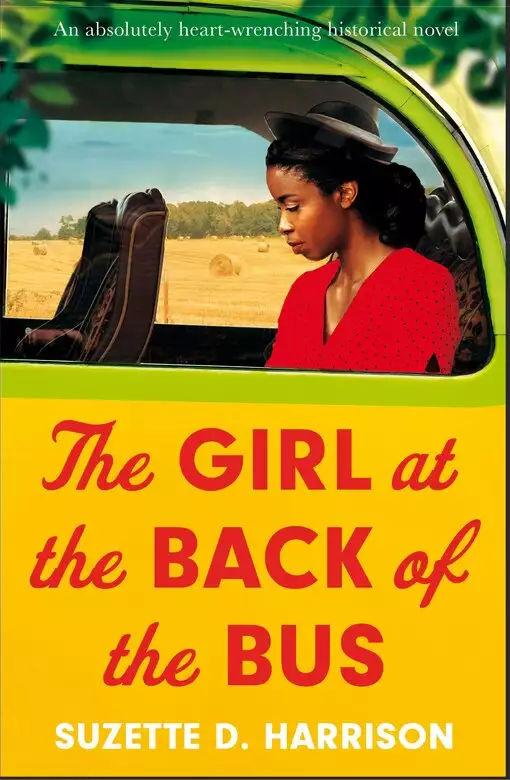

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved