- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

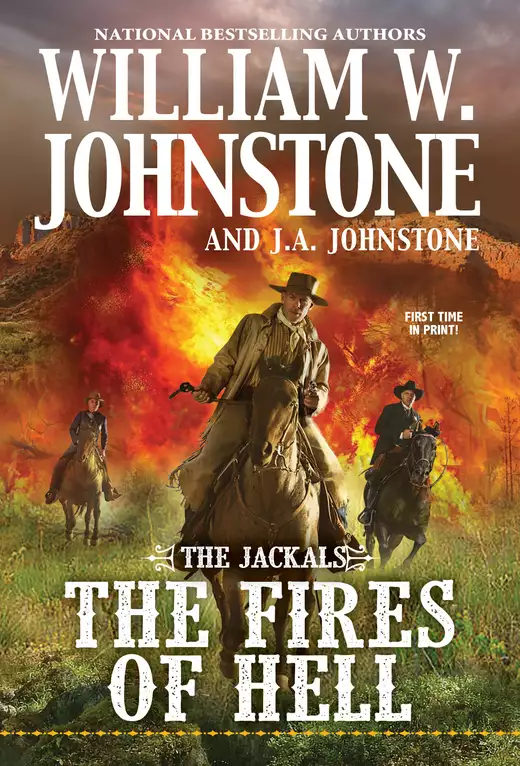

Synopsis

When a band of merciless, murdering thieves raise hell across the territory, three men committed to justice descend upon them like angels of death. And when the guns fall silent and the smoke clears, the Jackals are always the last men standing.

Comanchero Cullen Brice has escaped from a Huntsville, Alabama, prison, where he was sentenced to hang. And he has sworn revenge against the man who killed his brother and put him behind bars, Texas Ranger Matt McCulloch. Freed from the hangman by his gang, Brice has kidnapped the lawman's daughter Cynthia along with other women and make tracks to the Texas Panhandle. Holing up in The Canyon of Weeping Women, the outlaws plan to sell their captives to Comanche raiders.

Joined by bounty hunter Jed Breen and retired cavalry sergeant Sean Keegan, McCulloch rides hard for Texas, determined to save his daughter from Brice. But Cynthia isn't her father’s little girl anymore. And hell hath no fury like a woman raised by a Ranger who's just as deadly as the trio of Jackals gunning for Brice's comancheros . . .

Release date: January 24, 2023

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Fires of Hell

William W. Johnstone

Cover? The chunk of lead that had briefly blinded Keegan whined past Keegan’s right ear, slammed into the canyon wall a few feet behind him, and zinged back—the lead now cut in half. One chunk struck the rock about an inch or two from Keegan’s right arm, the one holding his Springfield carbine. The other spit up sand in front of Keegan and thumped harmlessly against the former cavalry trooper’s left boot.

“Confound it, Jed!” Keegan shouted to his partner. “I liked to have just been crippled on account of you.”

Another gunshot rang out from the dugout down the hill. That bullet hit the canyon wall and zinged off into oblivion.

Sean Keegan cursed again. Cursed, while cringing like a yellow-bellied coward or some greenhorn trooper. A soldier might eventually get used to the sound of gunfire, but the noise of a ricocheting bullet put the fear of the Almighty into even the most hardened veteran.

“Stick your head over that stone again, Sean.”

Keegan turned to give his meanest look at Jed Breen, but that was just a waste of effort.

The white-haired bounty hunter wasn’t even looking in Keegan’s direction. He crouched about twenty feet off to Keegan’s right, the barrel of his heavy Sharps rifle propped up in the “V” of his shooting sticks, the stock braced against his right shoulder, and Breen’s right eye staring through the long brass telescopic sight affixed to the barrel of the .50-caliber cannon.

“I mean it,” Breen said. His head never moved from the Sharps. Had he not spoken, Keegan could not have determined if his “ol’ pardner” in this affair were still living. A man couldn’t even tell if Jed Breen was breathing. He resembled some old juniper, dead but standing till Judgment Day.

“I didn’t join up with you to get my head shot off,” Keegan said.

“That’s a Winchester,” Breen said, still not looking away from the brass scope. “Not even a .44 caliber. Must be .38-40. We’re a hundred and thirty, forty, no more than a hundred and fifty yards away. And he’s shooting uphill. Not very much chance that he’ll shoot your head off. Thick as your skull is.”

Keegan felt his blood rushing again, the way it was prone to do when he found himself working alongside Jed Breen. That blood pressure might blow off his head.

“He still might kill me,” Keegan said.

“Didn’t say he wouldn’t kill you,” Breen said, still focusing on the dugout. “What I said was he wouldn’t shoot your head off.”

After choking down the curse, Keegan gathered his rifle and crossed his legs to see if that bullet fragment had done any damage to his boot. He could just make out a dent in the heel, but he had seen rougher damage done by mesquite and stones. So he twisted around, wiped his palms on his shirt front, and decided to look around the left corner of his boulder. Wetting his lips, he brought the Springfield’s barrel over, bracing it against a natural groove in the side of the granite, and aimed at the dugout.

He saw the flash below, the white smoke, heard the report of the Winchester, and felt the heat as the bullet screamed past his ear. That slug tore through a heart-shaped prickly pear and whined off another rock. No, not quite a whine. Just a ping.

But Keegan had pulled himself back, shaking his head, feeling the blood roaring like an express train, and tried to catch his breath.

“That must be Billy Ray,” Breen said. “Darn good shot, Billy Ray. Much better than his brother. With a rifle, anyway. Six-shooter, too. I don’t think Jim Bob was ever good at anything except with a running iron on other men’s cattle.”

“You told me that rustlers usually don’t put up much of a fight!” Keegan yelled.

“They aren’t just rustlers anymore. They are escaped convicts.”

Keegan’s mouth tasted like sand. He wanted to spit, but his tongue was drier than this patch of misery. “You could at least take a shot at those outlaws,” he growled. “So they wouldn’t keep taking potshots at me.”

Suddenly, Keegan got mad. He crouched, brought the Springfield to his shoulder, pulled back the hammer, and quickly spun around, fired, and ducked back behind the rock. The carbine’s report drowned out any satisfaction he might have gotten by hearing the bullet strike anything—man, dugout, tree, cactus, boulder, or even one of the two horses in the corral about twenty yards east of the dugout.

A moment later, he heard laughter from below. Then a Texas drawl: “That the best you can do, pardner?”

“No. Don’t have a shot.” Breen was calm as a night sky. And it took a moment before Keegan realized the bounty hunter was addressing Sean Keegan. “Dugout’s walls must be three feet thick, probably with some stone in there. Only one opening, the door, and whoever’s shooting is too far back for me to hit him. So I figure, let him waste his lead. I know what they say about a repeating rifle, that you can load it on Monday and shoot till Sunday. But that’s not true. And .38-40 cartridges are hard to find in this country.”

Five days earlier, Jed Breen had found Keegan outside a grog shop in Purgatory City. Keegan had known the bounty hunter mostly by sight and reputation until a few years ago when fate had brought the two together in a stagecoach station with Matt McCulloch, a horseman who had been kicked out of the Texas Rangers. Keegan had just been kicked out of the US Army, and Breen had always managed to rile citizens because of his occupation. A newspaper editor had labeled the three “Jackals.” ’Course, that newspaper editor was now dead and buried—but the name stuck.

Breen informed Keegan that the Hardwick brothers had escaped from prison, and the warden and state had posted a two-hundred-dollar reward for their capture and return.

“Huntsville,” Keegan had reminded Breen, “is a long way to go for two hundred bucks.”

“Not Huntsville,” Breen had said. “The Peering Farm.”

Keegan wasn’t quite drunk. “Peering Farm is not what I’d call close.” The farm was a cotton plantation, about as far into the Texas Panhandle as white settlers would dare go, even though most Comanches were now pinned up on the reservation near Fort Sill in Indian Territory.

“My guess is that the Hardwicks will ride south. Mexico.”

That made sense, at least it did at the time, so Keegan had asked: “What’s the split?”

“Fifty-fifty.”

A hundred bucks could keep a man drunk for a whale of a good time.

Now, with Keegan being shot at and sober, he began thinking about why he was here.

“What made you think those outlaws would try for Mexico?” he asked.

“Just a hunch.”

“Indian Territory’s a hell of a lot closer.”

“Indian Territory’s still in the United States.”

“But . . .” Keegan wiped his mouth. “It ain’t like ye, being a bounty hunter, got to get a warrant or a writ or whatever to haul two owlhoots back to Texas.”

Now, Breen moved. He lowered the rifle from his shoulder—he had to be stiff from keeping it aimed all this time—sat up, brought the big rifle beside him and stared across the hard canyon rim at his partner.

“What the hell do you care? We found them. Didn’t we?”

Keegan sniffed. “One of them . . . maybe.”

Breen rubbed the beard stubble on his chin. “One of them.” His whisper almost escaped Keegan’s ears.

“What are you getting at, laddie?” Keegan asked.

“Only one is shooting at us,” Breen said.

Keegan ejected the brass casing from his Springfield, thumbed a .45-70 shell out of the bandolier that hung across his chest, and set that round into the chamber. “You said Billy Ray’s the best with a long gun of them two.”

“Better,” Breen whispered. “Not best.”

“Huh?”

“Ramona’s been working on me to talk more like the educated man I am.”

“Huh.” Keegan brought the carbine closer. Ramona would be Ramona Bonderhoff, daughter of Purgatory City’s noted gunsmith. Keegan tried to picture Ramona and Breen together, found the image disgusting, and spit, though there wasn’t much to spit out of his parched mouth.

“One rifle, one man, one dugout. Two horses in the corral.” Breen talked as though he wanted to just hear the thoughts aloud.

“Like ye said . . . he’s the best shot,” Keegan said. “And those boys just escaped from a prison farm up at the southern edge of the Panhandle. Maybe they don’t got but one rifle. Maybe they—”

“Maybes,” Breen interrupted, “get a lot of men killed in this country.”

Keegan realized that Jed Breen was educated in many ways. So was Sean Keegan.

“Man trapped in a dugout wouldn’t be wasting his powder and lead.” Now Keegan started testing theories aloud himself. He had never tried that, but then he had always been the man of action, not the planning type. Jump into the fire and see what happens. He would not question how hot the fire might be. Or how much Irish whiskey he had consumed before making the jump. “He’d know, good of a shot as he is, the chance of hitting one of us would be slim.” He pulled off his hat, and sneaked a quick peek at the dugout. One of the horses in the corral was saddled, the other not. He wished he had thought to bring a spyglass with him. Breen had one, but it was hanging on the horn of his saddle. And they had left their horses at the top of the ridge, climbed down, and found themselves here.

When the first shot from the dugout sent Keegan to this spot and Breen to the other, both men figured they had been seen. Just a chance thing. Bad luck on their part. But the man with the rifle had scooted back into the dugout. And the standoff began.

“He didn’t yell for his brother,” Breen started talking now, and looked up the canyon wall. Where they had left their horses.

“And he didn’t try for the corral,” Keegan said. “Where one of those horses is saddled. Brush is thick down there. Some mighty big boulders, too. We both have single-shots. Good rider could have gotten away on a saddled horse.”

Breen peeked cautiously down the slope, came back to his position, and looked back at Keegan.

“Just one horse saddled,” he said.

“Aye, laddie. Aye.”

Now both were staring at the canyon.

“Those horses might be played out,” Breen said.

“Aye, they probably are,” Keegan said. “If they didn’t steal any riding south.”

“Not much chance to steal anything between Purgatory City and the Peering Farm,” Breen pointed out.

Except ours. The thought hit Keegan like one of Paddy Fitzsimmons’s haymakers back in those glorious days of the Rebellion, when the Irish boys would put on prizefighting exhibitions for those not blessed to have been born in paradise.

They heard the hoofbeats then. Both men sprang to their feet, brought their weapons up, pulled back the hammers, and saw one man—Jim Bob Hardwick riding Breen’s dun, pulling Keegan’s sorrel behind him—and aimed. Then ducked, falling flat on their faces, when Billy Ray Hardwick stepped out of the dugout and began sending. 38-40 slugs as quick as Paddy Fitzsimmons’s punches in the ring. One slug tore at the yellow silk kerchief around his neck. Another punched off Breen’s high-crowned black hat. Both men fell to the ground, letting out the vilest curses about their own stupidity.

Blithering idiot.

Jed Breen spit dirt out of his mouth. Cursed and cursed again when he saw the hole through his brand new hat, which had cost him two dollars and thirty-seven cents at Pendergrass’s mercantile in Purgatory City. Felt blood on his lips from the tough sand. He had bitten his tongue, to boot.

Everything had looked so perfect. Made to order. They had seen the smoke rising into the colorless sky late that morning, coming out of Fool Fassbinder’s Folly. That’s the name someone, thirty years or so earlier, had given this canyon. After the German settler, Fassbinder (the first name had long been forgotten), had settled in the canyon. No one knew, or remembered, his reason. There was no gold, no silver, nothing but granite and prickly pear, a few hardwoods, and a lot of hardships. But his dugout would always be a welcoming spot for travelers in this harsh country. Fassbinder, though, never knew about it, for the hostile Comanches—some say Kiowas—killed him shortly after he built his first fire.

Or so the legend went.

But Breen and Keegan knew of the canyon, and the smoke meant someone might be visiting. They wanted to make sure the fool at the dead fool’s dugout wasn’t the Hardwick boys. So they found the goat trail that led up the canyon, left their horses in a shady spot with some grain, and good, secure hobbles, and climbed down to the flat spot, found the cabin, and almost caught a bullet.

Now, however, Breen could picture in his mind exactly what had happened. Jim Bob Hardwick, always considered the better cowboy, had left his older brother in the dugout, ridden to the canyon’s exit, and waited. When he spotted two men riding toward him, he mounted his horse, galloped back to the corral, told his brother, and then he ran, afoot, to the canyon’s exit. Billy Ray started a fire, got the chimney puffing out smoke like a locomotive pulling a freight train up a steep mountain grade on a cold December morning. And while Keegan and Breen, two greedy sons of guns acting like two greenhorns, climbed down to get the drop on the outlaws, Jim Bob found their horses and stole them.

While Billy Ray, a fine shot with a puny little Winchester toy gun, kept Keegan and Breen pinned down with nothing much to do but pontificate. That would give Jim Bob time enough to find the horses, ride down the slope, come back to the canyon’s entrance, gallop back to the dugout to save his brother, and ride away, free to push on to the Rio Grande, swim that creek of a river this time of year, and live happily ever after in Mexico.

And it wasn’t like those boys were leaving two idiots to join Fool Fassbinder buried in this lonely canyon. The Hardwick boys weren’t leaving them afoot. They had two horses in the corral, which might or might not be lame. They even had a fire going, though it had to be ninety-one degrees right about now. They might be able to nurse their way back to Purgatory City, or maybe even up to Peering Farm.

Which made Jed Breen madder than a rattlesnake. The Hardwick boys were raising dust for the border—on Breen’s and Keegan’s horses. Two hundred dollars getting away—on mounts Breen and Keegan had paid good money for. Well, Jed Breen knew he had paid thirty bucks for his. Keegan might have won his in a boxing match, or found it and claimed it for his own.

Two hundred dollars did not amount to much. Jed Breen had brought in men worth far heftier rewards. But it was the principle that mattered. He dropped to his knee and brought the Sharps up tight against his shoulder.

“What the hell are you doing?” Keegan shouted. “You might hit one of the horses and not those English-loving dogs.”

“So?”

“Them’s our horses.”

“No,” Breen said calmly. He made the adjustments in his head. Shooting at a galloping target. Shooting downhill. Factoring in the wind. Always aim high. “I’m shooting your pile of glue bait.”

He let out a slight breath, smiled, relaxed, touched the set trigger, then shifted his index finger to the trigger that did the rest of the work. Smiling, Jed Breen squeezed. He was a professional. He ejected the massive brass casing, fished another from the pocket in his vest, and glanced at Keegan.

“My hundred dollars is heading for those rocks,” he said as he calmly reloaded. The Sharps had quite the range. “Yours is getting away. On my horse.”

That was all the motivation he needed to give the pesky, but good, Irishman.

Swearing, Sean Keegan brought his Springfield to his shoulder, pulled back the heavy hammer, and aimed at the fleeing rider.

“Remember . . .” Breen let the barrel of the Sharps cool slightly, then settled the big rifle to that familiar position. “You’re shooting a carbine. And a .45-70. You don’t have my range. And you’re shooting downhill.”

“And if I want to hire someone to teach me how to shoot a mad-dog killer, I won’t be hiring a low-down cur like you, pard.” Keegan had to calm himself down. He started taking so long to adjust his composure, Breen thought he might have to take the shot himself.

Just as he put his right eye near the telescopic sight, Sean Keegan’s Springfield roared. Breen lowered his rifle and looked over the brass. His horse was somersaulting off toward Mexico. In fact, it looked like it might roll all the way to the Rio Grande, which was four or five hard days’ ride from here. He saw the figure on the ground get up, turn, stagger, and fall. He saw the other escaped convict come from a small depression, run to his brother, and drag him behind a small rock.

Jed Breen nodded, and used the Sharps to push himself to his feet.

Sean Keegan did the same, the professional that he was despite a taste for barley and whatever grain they used in Irish whiskey. He thought it might also be barley, but it didn’t matter.

“Let’s go collect our bounty,” Breen said.

“What do we do for horses?” Keegan was reloading.

“I imagine the two nags they left behind will manage to get us to London’s ranch. That’s on the way to the prison farm.”

“They might still resist.”

Breen grinned. “They just got two horses shot from under them while riding at a full gallop. On a hard-packed, Texas-tough floor. I think they’ll enjoy being back in a prison where all they have to do is plant and pick cotton.”

He tucked the heavy rifle under his arm. But he kept his right hand on the holstered .38-caliber Colt Lightning—just in case.

How many times do I reckon I’ve done this?

Those kind of thoughts rarely entered Matthew McCulloch’s brain, and because of that, he stopped reaching underneath the brown mare’s belly for the cinch.

His pa once told him that Matt had saddled his first horse when he was five years old. His ma countered, No, he was six. His pa had said something like, Darn it, woman, I reckon I know when my son saddled his first hoss, and his mother had sung out something like, I begat you five boys and two daughters, and you can’t even get their names right half the time. And so it had gone till they yelled each other hoarse.

Five or six? Matt couldn’t recall. It just seemed like forever. He didn’t want to think about how old he was. The door to what passed for a home in West Texas shut, and the mare snorted and shook her head.

Hearing footsteps, Matt found the cinch and resumed his chore.

“I can saddle my own horse, Pa,” Cynthia called out. She was probably stamping her own feet right about then.

Matt finished the job without comment, then tugged on the horn to make sure the saddle felt secure. He looked over the saddle and smiled at the blonde he would always picture as a little girl, even though she was a woman full grown. And as pretty as her mother, God rest her soul. Maybe prettier.

He grabbed the reins and walked in front of the mare, extending the leather to Cynthia.

“You wouldn’t begrudge an old man for saddling his baby girl’s horse?” Matt smiled. Smiles, like thoughts about how many times he had saddled a horse, came rare to Matt McCulloch. But the look on his daughter’s face told him this was one habit he might get used to.

“As long as it’s not a sidesaddle,” Cynthia said.

He laughed out loud and pushed back the brim of his big Texas hat. “I ain’t seen a sidesaddle in this country in six years,” he said. “It belonged to Blanchefleur Boudoir. And she was . . .”

“A French lady?”

“Never you mind.” Blanchefleur Boudoir certainly wasn’t a lady. Ladies didn’t ride palomino horses sidesaddle wearing nothing but silk hose, thongs, and a delicate ribbon around her ponytail. And Matt didn’t think she had an ounce of French blood in her—not as thick as he remembered that Texas drawl sounded.

He extended his arm, and she took the reins.

“You got that pepperbox?” he asked.

Cynthia rolled her eyes. “Yes, Papa.” She carried a purse that hung over her shoulder. She opened it and let him see the well-worn handle of walnut. The pistol had to be twenty years old, maybe even twenty-five, and he wished he had something modern. Something that might not shoot off all six barrels instead of one when you touched the trigger. It was an Allen & Thurber pistol, .31 caliber. Matt couldn’t remember where he had gotten it, probably from an arrest back when he was Rangering. Next time he made it into Purgatory City, he’d visit Bondy the gunsmith and see if he had something more suitable, a Remington over-and-under. 41-caliber derringer seemed better.

“You know how to use it, right?” he asked.

“And I know when to use it,” she told him. Her eyes twinkled.

“Well . . .” He bit his lower lip and debated if he ought to accompany her to town.

She read his mind.

“You’ve got work to do here, Papa,” she said. “And if you had dinner with Ramona and me, you’d be so bored you’d fall asleep in your bowl of soup.”

“Soup?” Matt shook his head. “For dinner? I don’t reckon I’d be ordering soup.”

She smiled, until he pointed at the purse. “Now, Cynthia, just remember—”

His daughter cut him off, and slowly lifted the left side of her skirt. Above the boot he saw the Apache knife sheathed against the unmentionables around the calf.

“I can use this better,” she said. “And I will.”

Matt found himself at a loss for words. Fathers, he thought, never lost their tongue when warning daughters about all the dangers in this world.

“I’ll be fine, Papa,” she told him. “Purgatory City is becoming civilized.”

That’ll be the day, he thought, but kept his lips flattened.

The skirt dropped back over the boot. Cynthia had been kidnapped as a child during a murderous Apache raid. She had lived with the Apaches up until not quite a year ago, when Matt and his friends, Sean Keegan and Jed Breen, had helped rescue her deep in Mexico. She had been home since, reluctantly going to a school in Purgatory City until the teacher, Schoolmaster Markum, said she ought to be teaching him and the schoolkids. Now Matt looked at the miserable home he had been sleeping in for years. It was, he told himself, time to rebuild this ranch. And put his daughter in a real home. Not some hovel.

“All right,” he said. “Need . . . ?”

He didn’t have time to say “help” before Cynthia was in the saddle, smiling down at him.

“Have fun,” he told her. “Tell Bondy I’ll be in town in a day or week or so. Tell him howdy. And stay out of the saloons.”

She laughed.

“Get to the garden,” she told him. “Stay off of any widow-making broncs today.”

She let out a whistle, turned the horse around on a dime, and kicked the mare into a trot. By the time she rounded the corrals and found the trail to town, the dust from the galloping horse hid both daughter and mare from view.

Cynthia McCulloch, her papa marveled, rode like the wind.

Like her old man.

He cupped his hands over his mouth and cried out: “Make sure you’re back before dark!”

She probably couldn’t hear him over the pounding of the mare’s hooves, but she would be back before dark. She was a good girl. She’d always been a good girl. He told himself that Purgatory City wasn’t that far—not that it was close—and maybe Cynthia was right. This part of West Texas was, ever so slowly, getting close to being civilized.

He pulled off his hat and used it to slap the dust off his chaps.

He told himself: Close to civilized ain’t exactly civilized.

He ran his free hand through his hair.

When was the last time he had looked into a mirror? He ran his fingers across the stubble on his cheek. Last time he shaved, most likely, he answered to himself. Three days. Maybe four from the feel of the beard. And how many more gray hairs have sprung up since Cynthia returned home?

I’ll be white-haired like Jed Breen, he thought, before I know it.

Daughters. He shook his head. They had a way of aging a daddy.

But it was a mighty good way to grow old.

Two hours later, he found himself hoeing weeds in his garden.

Gardening. Like a farmer. Yes, the newspapers in the great state of Texas would h. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...