- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

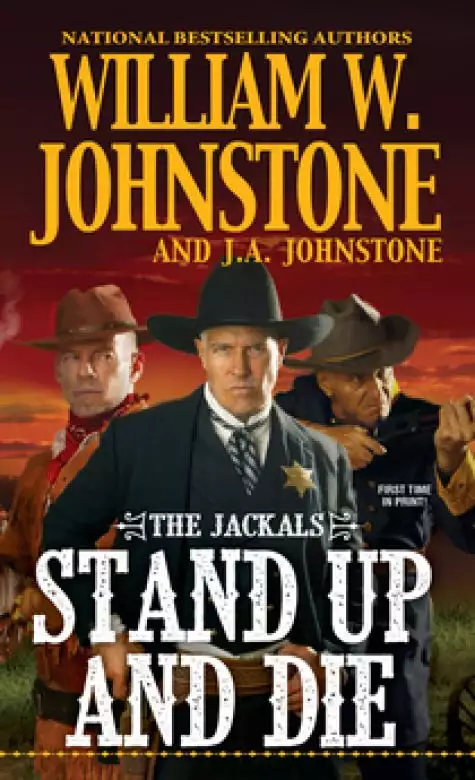

The wild bunch known as the Jackals returns for another round of justice served cold, hard, and with as many bullets as it takes. Nationally bestselling authors William W. and J. A. Johnstone are at it again . . .

Some say bad luck comes in threes. And if you're a bandit, bank robber, or bloodthirsty killer, that bad luck comes in the form of three hard justice-seekers known as the Jackals. Each of the Jackals has his own path to follow: Former Texas Ranger Matt McCulloch is trying to protect a young Commanche from scalphunters. Retired cavalry sergeant Sean Keegan is dodging bullets in a prison breakout planned by the notorious Benteen brothers. And bounty hunter Jed Breen is bringing in one of the bank-robbing Kruger twins—while the other one's out for his blood . . .

Three Jackals. Three roads to justice. But when their paths cross near Arizona's Dead River, they've got to join forces and face all of their enemies come hell or high water. They don't call it Dead River for nothing . . .

Release date: September 29, 2020

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Stand up and Die

William W. Johnstone

As he crouched by the campfire along Limpia Creek, sipping his last cup of coffee before starting his day, Matt McCulloch smiled. It was a pleasant memory, that conversation he recalled having with his wife shortly after they had married. She thought they should settle here, grab some land. There was good water—though you might have to dig pretty deep to find it—enough grass to feed cattle and horses, an army post for protection, and a thriving, friendly town, with churches, a good restaurant or two, and a schoolhouse so that their children, when they got around to having children, could get a good education. But McCulloch had figured he could get more land for his money farther west and south, so they had moved on with a farm wagon, a milk cow, the two horses pulling the wagon, the horse McCulloch rode, and the two broodmares tethered behind the Studebaker that carried all their belongings.

Yeah, McCulloch thought as he stood and stretched. All their belongings. They’d had a lot of extra room in the back of that wagon to collect the dust as they traveled on, eventually settling near the town of Purgatory City . . . which wasn’t so pretty unless you found dust storms and brutality pleasant to the eyes . . . where churches met whenever a lay preacher felt the call . . . where the schoolhouse someone built quickly became a brothel . . . and where the best food to be found was the dish of peanuts served free to patrons at the Perdition Saloon.

He tossed the last mouthful of the coffee onto the fire and moved to the black horse he had already saddled, stuffing the cup into one of the saddlebags. Found the well-used pot and dumped the last of the coffee, hearing the sizzle, letting the smoke bathe his face and maybe blind him to any bad memories, make him stop thinking about that dangerous question What if ?

Would his wife and family still be alive had he settled here instead of over there? Would his daughter not have been kidnapped, never to be found again? Taken by the Apaches that had raided his ranch while he was off protecting the great state of Texas as one of the state’s Rangers?

Besides, even Purgatory City wasn’t as lawless as it had once been, especially now that a certain contemptible newspaper was out of business and its editor-publisher-owner dead and butchered. Even the Perdition Saloon had been shuttered. After a couple of fires and a slew of murders, the owner had been called to rededicate his life after learning that he had come down with a virulent case of an indelicate disease and inoperable cancer on top of that. The Perdition Saloon was now—McCulloch had to laugh—a schoolhouse. The city still boasted five other saloons, and all did thriving business when the soldiers and cowboys got paid, although Texas Rangers and some dedicated lawmen generally kept a lid on things.

He kicked rocks and dirt over the fire, spread out the charred timbers, and stuffed the pot into the other saddlebag.

McCulloch was getting his life back together, had even begun to rebuild that old ranch of his. Not much, not yet anyway. Three corrals, a lean-to, and a one-room home dug into what passed for a hill. It was enough for him.

The corrals were empty, but horses were what had brought Matt McCulloch to the Davis Mountains. Wild mustangs roamed all over these mountains, and he had decided it was a good time to get back into the horse-trading business. Find a good herd of mustangs, capture those mares, colts, fillies, and the boss of the whole shebang. Break a few, keep a few, and sell a bunch. It was a start, a new beginning. All he had to do was find a good herd worth the bruises and cuts, and maybe broken bones, he would get trying to break them.

Folks called the Davis Mountains a “sky island,” and McCulloch knew his late wife would have considered that pure poetry. The sea was just sprawling desert, flat and dusty, that stretched on forever in all directions. But nearby greenery and black rocks, rugged ridges and rolling hills rose out of nowhere, creating an island of woodlands—juniper, piñon, pines, and aspen. Limpia Creek cut through it, and canyons crisscrossed here and there like a maze.

He had a square mile to cover, six hundred and forty acres, but he could rule out much of the high country, those ridges lined by quaking aspen trees. So far, all McCulloch had seen were wild hogs, a few white-tailed deer, one antelope, and about a dozen hummingbirds. But he had also seen the droppings of horses—and the scat of a black bear.

He stepped into the stirrup, threw his leg over the saddle, and moved south to find the grasslands tucked in between slopes where a herd of mustangs would be grazing. Keeping one eye on the land and one eye scanning for any Indian, outlaw, snake, or some other sort of danger, he noticed that the black bear must have had the same idea. Well, an old mare or a young foal would make a tasty meal for a bear.

McCulloch stopped long enough to pull the Winchester from the scabbard.

When he came upon the next pile of excrement the bear had left, he swung out of the saddle, and broke open the dung with his fingers, rubbing them together. He smiled, picturing the looks on the faces of his wife and daughter had they been around to witness it. He could hear both of them screaming to go wash his hands in lye soap. Quickly, he shut off those thoughts, not wanting to ruin such a beautiful morning with a burst of uncontrollable rage at God, his life, his decisions, and this tough country where he had tried to make a life.

All right. The scat was about a day or so old. A mile later, when the bear had started up the mountain, McCulloch did not follow. But he did keep an eye overhead.

Eventually, he forgot about the bear, for something else commanded his attention—tracks left by unshod horses. And not of a war party of Comanches, Kiowas, or Apaches. He dismounted for a closer look. No, some of the tracks belonged to youngsters, the colts that eventually might challenge the big stallion leader. It was a big herd, too, and McCulloch thought how he would handle such a large bunch. He’d have to trap them at a water hole or in a canyon. Do some breaking there. Then drive all he could all the way to his spread to start the real work. The bone-jarring, backbreaking work.

He was about to mount his black horse when something caught his eye. He moved a few yards away and sank his knees, protected by the leather chaps he wore, into the dirt. One of the horses he was following wore iron shoes. The rear hooves had been shod. Maybe a mare had wandered into the herd from some ranch or farm. Perhaps it had lost the iron shoes on its front feet. But some men in these parts were known to put shoes on only the rear feet of their mounts, so McCulloch might have competition for the herd.

Texas, he reminded himself, was a free country.

The other thought that crossed his mind, however, was that whoever was trailing this herd—if that indeed were the case—might not like competition. Especially if the horse had been stolen by an Indian.

His own horse had four iron shoes. Traveling across the volcanic rock and stones that lined the trail he had to follow would produce far too much noise. He leaned the Winchester against a rock and fished out leather pads from a saddlebag. These he wrapped around the black’s feet, and the heavy hide would muffle the noise of his horse’s footfalls. Carbine back in hand, McCulloch mounted the horse, and rode through the canyon.

When he came into the opening, he didn’t see the horse herd, but he found the black bear.

It lay dead at the base of a rocky incline to the east.

McCulloch reined in, dismounted, and wrapped the reins around the trunk of a dead alligator juniper. The blood from the dead bear made his horse skittish, and the last thing McCulloch wanted was to be left afoot in this country. He stepped a few feet away from the horse and squatted, studying the country all around him, including the dead bear. No birds sang, no squirrels chattered, and the wind blew the scent of death and blood across the tall grass. Fifteen minutes later, he moved closer to the bear, seeing the drying blood soaking the ground.

The bear hadn’t been dead very long, McCulloch thought after he reached his left hand over and felt the thick fur around the animal’s neck. His fingers ran across the stab wounds. Knife? Lance? Certainly not the claws from another animal. Wetting his lips, McCulloch again looked across the canyon, up and down, and listened, but the only sound detected came from the stamping of the black’s hooves and the wind moaning through the rocks and small trees.

He moved to the bear’s head and saw the flattened grass and the blood trail that led into the rocks. Whoever had killed the bear had been wounded and dragged itself—no, himself—into the hills. A busted Spencer carbine lay in the grass, and McCulloch saw the holes in the bear’s throat. Two shots that had done enough damage, caused enough bleeding, to end the bear’s life, but not before that bear had put a big hurt on the . . . Indian.

Most likely, McCulloch figured, seeing the beads scattered about the scene of the tussle and the studs that had been nailed into the broken Spencer’s stock. He spotted one eagle feather that had been caught against a jagged bit of rock.

“Now what?” he whispered.

The Indian likely crawled into the rocks. Maybe to die. McCulloch didn’t see the Indian pony, but when a bear comes charging at you, horses run like hell. If that horse with two rear iron shoes hadn’t been part of the mustang herd, it might have joined up already. Even wild horses and trained horses knew the value of teaming up in numbers in that part of the United States.

He looked up at the rocks, and again at the trail of blood and trampled grass. The wind cooled him. Despite the morning chill, he had started to sweat. He had lived too long to risk his hide going after a wounded Indian. Besides, the bear and maybe the Indian had made finding that herd of mustangs a whole lot harder.

McCulloch rose, moved to the side of the rocky wall and slid around the bear. Stepping back a few feet, he looked up the mountain and listened again. Still nothing but the wind. Not completely satisfied but in a hurry to get after those mustangs, he decided to make for his horse. He didn’t think the Indian would have another long gun. Maybe a short pistol, but probably nothing more than a knife. Odds were McCulloch could make it to the black, mount up, and ride away without any trouble. Better odds were that the Indian had bled out and would soon be feeding javelinas and coyotes.

Three steps later, McCulloch leaped back, more from instinct and that hearing he prided himself on. Even then he almost bought it. The knife blade sliced through his shirt, through flannel and the heavy underwear. The Winchester dropped from McCulloch’s hands and into the dirt as he staggered away. Blood trickled.

The Indian came at him again.

Sean Keegan had been drummed out of the United States Cavalry after saving the lives of a bunch of new recruits but having to shoot dead a stupid officer who was inclined to get everyone under his command killed. Keegan had learned to accept the fact that he no longer wore the stripes of a sergeant, no longer had a job to whip greenhorns into shape and teach green officers the facts of surviving in this miserable country of Apaches, Comanches, rattlesnakes, cardsharpers, bandits, hornswogglers, and various ruffians.

He often missed that old life he had led, but every now and then he came across the opportunity to relive some of that old glory.

The morning proved to be one of those times.

Purgatory City had become civilized, damned close to even gentrified, with marshals, sheriffs, Texas Rangers, city councils, school boards, churches, and a new newspaper that wasn’t the rag that old one had been. The editor kept preaching—along with the Catholics, Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Hebrews, and Lutherans—about the need for more schools, better roads, a bridge or two, and higher taxes on the dens of iniquity that allowed gambling, dancing, ardent spirits, and, egads, in some cases . . . prostitution. But there was one place a man could go and feel like Purgatory City remained a frontier town.

The Rio Lobo Saloon, although no river named Lobo flowed anywhere in the great state of Texas, and certainly not one in the vicinity of Purgatory City. The saloon had been open seven years and had not closed its doors once. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week—no matter how much the Baptists raised holy hell—serving liquor that would either put hair on a man’s chest or burn off the hair he had on his chest. Potent, by-gawd, forty-rod whiskey that would make Taos Lightning seem like potable water. Even that fire that had swept across the bar two and a half years back had not shut down the Rio Lobo, and Sean Keegan had done his best, starting the fire and the fistfight that landed him in jail for thirty days and got him busted, briefly, back down to mere trooper.

Keegan had arrived the previous afternoon, ate the sandwiches the bartender set out for free to patrons paying for their drinks, did a couple of dances with the prettiest chirpies, put a good-sized dent in the keg of porter, arm-wrestled the blacksmith Winiewski, and lost, that was fine. Nobody had bested the Polish behemoth in four hundred and eighty-three tries, but it took the smithy seven minutes before he damned near broke Keegan’s wrist and forearm.

Finally Keegan found a seat in a friendly poker game at about two-thirty that morning, and set down with a bottle of Irish and seventeen dollars and fifteen cents.

When the game broke up while the Catholic church bells were ringing eight times, and folks were opening their shops on Front Street, Keegan tossed the empty bottle toward the trash bin, missed, and smiled at the sound of breaking glass and the curses of Clark, the barkeep.

“It’s been a fine game,” Keegan said, grinning at the dealer, and sliding him a double eagle. “But I suppose all good things must come to an end.”

“Thank Queen Victoria for that,” said the weasel in the bowler hat.

The railroad hand with the ruddy face leaned back in his chair and waited for Sean Keegan to react.

“The hell did you say?” Keegan asked, though he wasn’t sure if he was looking at the right pipsqueak, since for the moment he saw two, and both of them were fuzzy.

“I said thank Queen Victoria that you’re leaving. You took me for better than two hundred dollars.”

“Queen”—Keegan closed his eyes tightly—“Victoria?”

“Yes.”

When his eyes opened, Keegan saw only one runt of a weasel.

“She’s your queen.”

“The bloody hell she is. She’s the queen of England. I’m Irish,” said Keegan.

“She’s the queen of England and Ireland, and, if I remember correctly, Empress of India.”

“She’s a piece of dung like every other English pig, sow, and hog.”

The runt rose and brought up his fists. “You shall not insult Queen Victoria in front of me, you drunken, Irish pig.”

What confused Keegan was that he didn’t detect one bit of an English accent rolling off the weasel’s tongue, and while he was trying to figure out why a drummer in a bowler hat who didn’t sound like a Brit would bring up Queen Victoria in West Texas, the little weasel punched Keegan and split both of his lips.

He had been leaning back in his chair, trying to clear his head, and wound up on the floor, tasting blood and seeing the punched-tin ceiling of the saloon spin around like a dying centipede.

Chair legs scraped as the bartender said, “Oh, hell.”

Keegan rolled over and came to his knees, just as the weasel brought his right boot up. The boot, Keegan later recalled, appeared to be a Wellington, which didn’t make the runt an Englishman but hurt like hell, and sent Keegan rolling toward the nearest table.

“I’ll teach you to libel Queen Victoria and servants of Her Majesty.”

The Wellingtons crunched peanut shells and a few stray poker chips as the weasel rushed to give Keegan another solid kicking, but Keegan came up with one of the chairs from the nearest poker table, and the chair became little more than kindling after he slammed it into the charging, puny devil.

“Keegan!” the bartender roared.

Out of the corner of his eye, Keegan saw the bartender lifting a bung starter and removing his apron.

Keegan figured that would give him enough time to pick up the bleeding, muttering, sobbing fellow and throw him through the window, which he did. As the glass rained across the boardwalk, hitching rail, Front Street, and the now quiet weasel, Keegan turned to meet the morning-shift barkeep and saw something else.

The railroad worker was helping himself to some of Keegan’s winnings.

“You damned sneak thief.” To his surprise, he realized he still held the broken chair leg in his right hand. The railroad thug swore, tried to stuff some more coins and cash into his trousers pocket, then grabbed the pipsqueak’s chair and came after Keegan.

“You men stop this!” the bartender yelled. “You’ll wreck this place!”

Like that had never happened before, Keegan thought with a smile and a few fond memories about previous times when he had tried to shut down the Rio Lobo Saloon. He’d never been able to manage it, but he had done his best, bless his Irish heart.

The railroad man was used to swinging sixteen-pound sledgehammers, and lacked the savvy needed for surviving saloon brawls. He brought the entire chair over his head, likely intending to slam it hard over Keegan’s head, but as he swung that chair back toward Keegan, the old army sergeant jammed the broken chair leg in the man’s solid gut.

Not the broken, jagged end. This wasn’t one of those kinds of fights. That would have likely proved to be a mortal wound, and the way Keegan had it figured, this fight was on the friendly side. He was surprised, though, at how hard that man’s belly was. The big man grunted and his eyes bulged, but the chair kept right on coming, and the next thing Keegan knew he was rolling on the floor again, bleeding from his scalp and nose, and his shoulders and back hurt like blazes.

But he came up quickly, saw the railroad man shaking his head to regain his faculties, saw the barkeep slipping on a pair of brass knuckle-dusters, and saw the house dealer, still at the table, rolling a cigarette and counting his chips.

Keegan grunted, spit out blood—but no teeth—and lowered his shoulder as he charged. He caught the railroad man in the side, just above the hip, and drove him all the way to the wall. The impact caused both men to grunt, two pictures to fall to the floor, and the bartender to curse and scream that he would kill the both of them if they didn’t stop right this minute.

The railroad man’s head faced the wall. He had lost his railroad cap, but had a fine head of red hair. Hell, maybe he was Irish, too, but it didn’t matter. Keegan latched on to the hair, jerked it hard, and then slammed the man’s forehead against the wall of pine planks. Another painting hit the floor. Keegan pulled back the man’s head and let it feel pine again. The pine had to be expensive to get all the way from wherever you could find pine trees to the middle of nowhere that was Purgatory City.

He pulled the head back and was going to see if he could punch a hole in the wall and give the Rio Lobo Saloon a new door, but the railroad worker’s eyes had rolled back into the head, so Keegan let the man drop to the floor.

Besides, the bartender was bringing back his arm to lay Keegan out with those hard brass knuckles. Keegan ducked, felt the man’s right sail over his head, and heard the crunch as the barkeep’s fist slammed into the wall where there was no painting—actually a cut-out from some old calendar that had been stuck into the frame—to soften the blow.

The barkeep screamed in pain and grasped his right hand with his left. Tears poured like he was some little baby, and Keegan figured those broken fingers must hurt like hell. They’d likely swell up, too, so that fool would have the dickens of a time getting those knuckle-dusters off. Hell, the doc might have to amputate his hand.

That wasn’t Keegan’s concern. He grabbed the man’s shoulder, spun him around, slammed a right into the stomach, a knee into the groin, jerked him up, pushed him against the wall, and let him have a left, right, right, left, and finally grabbed his shoulders with both hands and hurtled him across the room. He caught the closest table, slid over it, knocked down and busted a chair, and lay spread-eagled on the floor.

After sucking his knuckles, Keegan went back to the railroad man and pulled out most of the money the thief had tried to steal. He did leave a few coins, chips, and greenbacks to help pay for the man’s doctor bill, and for damages, and a tip for a hell of a fun fight.

He then went back to the poker table where the dealer raised his coffee cup while sucking on his cigarette, and smiled.

“Nice fight, Keegan,” the dealer said.

Keegan knocked him out of his chair. The man rolled over, his cigarette gone, his coffee spilt, and lifted himself up partly, leaning against a cold stove.

“What the hell was that for?” the dealer demanded.

Keegan gestured toward the unconscious railroad worker. “For not stopping him from lifting my winnings.” He stepped back to the table, and began getting the rest of his money, but kept his eye on the dealer.

The batwing doors at the front of the Rio Lobo rattled, and Keegan recognized a familiar voice.

“Sean, let’s take a walk to the calaboose, old friend.”

Keegan laughed, shoved the winnings into his pocket, tossed a greenback at the dealer, and dumped some more money on the felt top of the table. “For damages,” he told the dealer, nodded good-bye, and walked to the old man waiting with the handcuffs.

“Sergeant major,” Keegan told the old horse soldier from Fort Spalding.

“It’s deputy marshal these days,” Titus Bedwell said. “Retired from the army a few months back.”

“Buy you a drink, Titus?”

“After you’ve served your time, Sean.”

Keegan shook his head at the handcuffs. “You don’t need those, Sergeant major.”

“That’s good to know. Let’s take a walk.” Bedwell pushed open one of the doors and nodded at the dealer standing in the back of the saloon. “I’ll let you know, George, if and when you need to testify. And when Millican comes around, have him get with Clark and figure out the damages. But don’t cheat Keegan after what he has paid you already.”

Bedwell and Keegan walked down the street, Keegan admiring the stares from men and women alike, and laughing as others cleared off the boardwalk to let them pass. When they reached the city jail, Bedwell opened the door, and Keegan walked in and made his way toward his cell.

“Not that one, Sean,” Bedwell said.

Keegan stood at the iron door, grabbed the bars, and stared inside.

“Get out of my face,” the dark figure on the bunk said bitterly.

Keegan turned, and Bedwell grabbed a set of keys. “That’s Tom Benteen, Sean. We’re hanging him tomorrow.”

Whirling, Keegan tried to get a good look at the man in the bunk. Tom Benteen. The Benteen brothers and their old uncle, Zach Lovely, and cousin Tom—who had taken the Benteen name after getting sick and tired of folks making jokes about being Tom Lovely or Lovely Tom—had been rampaging across Texas for four years, robbing banks, trains, killing two sheriff’s deputies, a judge, a jailer, four bank tellers, two railroad conductors, and one lawyer from San Angelo . . . but no one cared much about the lawyer.

“How’d you catch him?” Keegan asked.

“Jed Breen brought him in.”

“Alive?” Ke. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...