- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

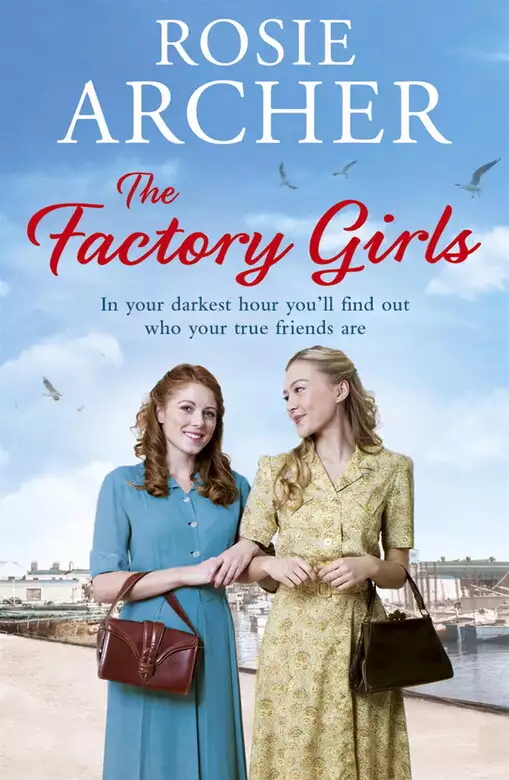

Synopsis

It's 1944, after D-Day. Doodlebugs are the latest threat to war-battered southern England. Local crook Samuel Golden is still finding ways to exploit people's hardship for his own gain. Heroine, Em, who we first met in The Munitions Girls, finds herself caught up in one such scheme whilst having to deal with her daughter's unexpected pregnancy. Female friendship; wartime drama; mothers and daughters; and finding a good man in the end - it's all there in this sparkling new saga from Rosie Archer.

Release date: August 11, 2016

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 407

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Factory Girls

Rosie Archer

1944

‘She said, “I’m your sister!”’

Em Earle stared at her friend Gladys, whose mouth had fallen open in astonishment at her words. Dropping her clipboard, Em made a dash for the door and the lavatory beyond.

Eventually, in the cubicle, Em looked up, relieved that Gladys had followed her. She took a handkerchief from her pocket and wiped her mouth. The wireless playing cheery dance music in the munitions factory didn’t make her feel happier, nor did it erase the memory of her encounter last night with Lily Somerton.

Gladys asked, ‘Feel better?’ She took her own clean hanky from her sleeve and passed it to Em. ‘You ain’t never had a sister!’ Em could see the shock on her friend’s face.

She had worried all night, unable to sleep a wink. Now she straightened up, tightened the belt of her navy blue dungarees and tucked away some strands of hair that had worked themselves loose from her white turban, which was standard uniform for the workers at Gosport’s Priddy’s Hard.

Gladys put her arms around her. ‘There must be some terrible mistake, Em. I’ve known you for years and I’m the nearest to a sister you’ve ever had. We’ll work this out somehow.’

The humming of the machinery suddenly reminded Em that she should be attending to her job of supervising the women on the line. She needed to be on watch at all times as they filled and tamped the dangerous fulminate of mercury into copper shell cases. The light brown powder was very sensitive and highly toxic. One wrong move and they could be blown to kingdom come.

‘This Lily’s returning tonight with some documents, proof, she says.’ She looked pleadingly at her friend. ‘Gladys, will you come round to the house?’ Em heard doors opening and voices, footsteps coming towards the lavatory. ‘We can’t talk here,’ she said.

Gladys agreed, then shook her head, the bleached blonde curls over her forehead dyed orange from the toluene vapour and acid droplets that discoloured the workers’ hair and skin, and made the women sleepy. It also poisoned the air in the workshops. In some cases women lost teeth, but these were known hazards of munitions work. Even the ointments provided for the skin rashes rarely helped. ‘Canaries’ was the nickname for the girls working in munitions.

‘Seven?’

Em nodded.

‘You sure you’re all right?’

‘I am now,’ Em replied. She squeezed her friend’s hand and took a deep breath as Gladys handed her clipboard back to her. The women in the workshop depended on her.

Priddy’s was named after Jane Priddy, who in 1750 originally owned the forty acres of land. It was one of England’s main suppliers of armaments, shells, rockets, mines and ammunition. The work was exhausting and dangerous and shifts were twelve hours long, repetitive and mind-numbing. Em needed to be calm and clear-headed should any unexpected incident occur. She smiled at Gladys and they walked back to the workshop arm in arm.

The day whirled by and Em tried not to dwell on the previous evening. But her thoughts returned time and time again to the knock on the door.

Dragging down her daughter Lizzie’s blouse from the wooden drying rack suspended from the kitchen ceiling, she’d spread the garment over a folded blanket on the table. Using an iron holder she’d sewn from bits of padded rag, she reached for the flat iron on the gas stove. Em spat on its base, her spit sizzled, and she wiped the iron on an old rag.

She was listening to Much Binding in the Marsh on the wireless. Lizzie might need the blouse when she returned from Lyme Regis, where she’d been living for some months. Em received the odd letter from her. Never much news, just a note reassuring her mother that she was well and happy in her bar job. Remembering Lizzie made her think about her other daughter, Doris, and her little boy living with her foster mother, and the letters she regularly sent.

Em was pleased that Lizzie was far away from the bombing but she failed to understand why her daughter had felt the need to leave Gosport and her job at the armament factory so suddenly. She often wondered if it had any bearing on the disappearance of Lizzie’s boyfriend, Blackie Bristow, who previously had been her friend Rita Brown’s lover. Perhaps memories of the handsome rogue and the love they’d shared, the places they’d visited together in Gosport, had hurt Lizzie too much to stay.

The one thing Em was grateful for was that Sam, her friend and the manager of the Fox public house in Gosport town, had found the job for Lizzie and she knew that he cared too much for Em to put her daughter in danger.

The knock on the door had startled Em.

A blonde woman wearing lots of red lipstick stood on the doorstep. She was attractive in an overblown way. Despite the warm weather she had on a fur coat and Em thought she must be terribly hot.

‘Are you Em Earle?’

Em nodded, and the woman had continued. ‘You might want to sit down for what I’m about to tell you.’

Fear had overwhelmed Em. ‘Is it my daughter? Has something happened to her?’

The woman had leaned forward, putting a hand on Em’s arm.

‘No,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘Look, we’d better go inside.’ Without waiting for a reply, she’d pushed past Em and strode through into the hall.

Em had followed her into the kitchen, protesting, ‘You can’t just barge into my house. Who d’you think you are?’ She was angry she’d allowed the woman to invade her privacy.

The woman turned towards her.

‘I’m Lily Somerton, your sister,’ she said.

The words had taken a long time to sink in. Sweat prickled the back of Em’s neck.

Finally she blurted out, ‘I don’t have a sister!’ Shaking, she pulled out a kitchen chair and practically collapsed into it, her heart beating wildly.

The woman, who up until then had just been staring at her, began looking around the kitchen. Her eyes alighted on the kettle which she promptly began filling.

‘I think you need a cuppa,’ she said. Her voice was softer now. Em, her head still reeling, stared at her, watching her quick movements as she set about spooning a miserly amount of tea into the pot without rinsing it. She hated using the leaves over and over until the tea resembled dishwater, but with only two ounces of tea per person a week, what else could she do?

They were of a similar height, and like Em the woman was nicely rounded. Unlike Em, she wore a lot of make-up, with thick, black mascara emphasizing her eyes. Beneath her fur coat, which she was now in the process of removing, she wore a blue dress patterned with small flowers. The sweetheart neckline showed off her ample bosom. Em thought the woman was in her thirties, like her. A thought struck her.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Lily, I told you that. I was married, hence a name change, but the name I grew up with was Symonds, for the couple that adopted me. My birth certificate says I’m Lily May Green. You’re Emily Rose Green, or was before you married Jack Earle . . . I think Mum must have loved flower names.’

‘You know a lot about me . . .’ Em broke in.

‘I had to find out everything. Couldn’t make a mistake, could I?’ She was stirring the pot and had the teacups sitting on a tray on the table, next to the iron that was now cooling on a wire rack.

Em’s head was still whirling but she managed to ask, ‘I suppose you’ve got proof of this?’

The woman nodded. ‘Plenty. I was given away, and the following year you were born. We’ve got the same father.’ She paused and frowned. ‘At least, it looks like it. His name’s on both our birth certificates.’

‘I’m surprised you’ve seen a copy of my birth certificate.’ Em wasn’t used to people prying into her private life. She thought about her mother who, before she died, had begged to be buried with her husband. Em had seen to it that she was. During the fifteen years between their deaths her mother had never so much as looked at another man.

If this woman was telling the truth, how had it all come about?

Lily sat down on the kitchen chair next to her. She was wearing a flowery perfume that smelled heady and made Em think of bluebells. She took Em’s hand. Em saw her nails were painted with colour the exact shade of her lipstick. Em hadn’t been able to buy nail varnish for ages. There wasn’t any in the shops.

‘Look,’ said Lily, ‘I know this is a terrible shock to you. But I’ve been looking for my sister for years. It’s taken me until now . . .’ She paused, and Em saw that her eyes were blue, just like her mother’s had been. ‘It’s taken me until now to find out what happened and why I was given away.’ She gave a huge sigh. ‘I used to look at friends at school and envy them their sisters. Now I’ve found you I want us to be friends.’

Em removed her hand. ‘You can’t just walk in here, bold as brass and expect me to believe you—’

‘No,’ broke in Lily, ‘that’s why I want to come back tomorrow, if that’s all right?’ She waited for Em to nod in agreement, and then added, ‘I’ll bring my folder with all the proof in it.’

She rose from the chair and went to her coat, picked it up and put it on. Em didn’t speak. It was, she thought, as though she was watching a film and didn’t know what was going to happen next. Lily paused and turned to look at her before leaving the kitchen.

Em called out to her, ‘You’ve not had your tea!’ Steam was coming from the pot’s spout.

She got up to follow the woman, but already Lily had opened the front door and was walking through the gate.

Again she turned and looked at Em. ‘I don’t want to bother you any more. It’s a lot to take in. You need to think about things, to get over the shock.’

And then she was gone, walking down the street with her black handbag and gas mask dangling over her arm and her high heels click-clacking on the pavement. As she reached the Queen’s Hotel, with its huge wooden girders holding up one wall where Queen’s Road had taken a real thrashing from the German bombers, she stopped, looked back and shouted, ‘Tomorrow? At seven.’

Earlier the rain had drenched the gardens, and the June evening was cool now. Her head still reeling, Em closed the front door.

Oh, how she wished Lizzie were still at home. Back in the kitchen she picked up her daughter’s photograph that stood on the window sill. The pretty girl with long dark hair smiled back at her.

‘Oh, Lizzie,’ she said. ‘Whatever is this all about?’

Then she looked at the clock on the sideboard. She needed to talk to someone, desperately. Em replaced the photograph. Gladys would be home but by the time she’d walked to Alma Street it would be nearly ten o’clock. It wouldn’t be fair to worry her friend, not when they both had to get up early for work tomorrow.

She wondered whether she should go down to the Fox and have a word with Sam. He was a good listener and would do anything for her. She pushed that thought away. The pub wasn’t closed yet and she couldn’t face waiting for him to shut the bar and clear up before she could get his full attention. Lovely man that he was, it wouldn’t be right to involve him in her problems, not when she should be at home getting enough rest to face the possible hazards of her job tomorrow.

In the kitchen she poured herself a cup of tea. Sitting at the table with the iron, blouse and blanket almost forgotten about, she drank the hot liquid. Eventually she went upstairs. It would be a long time before she slept tonight.

It might be nice to have a sister, she thought as she pulled her flannelette nightdress over her head.

Em felt her stomach rebel against the tea and the shock.

Her head was thumping and her body began to shake. She managed just in time to pull the flowered chamber pot from beneath the bed before she threw up.

Chapter Two

The old man used both of his gnarled hands to lever himself up from the high-backed chair. Joel Carey could see the difficulty he had grabbing his stick to manoeuvre himself across the room to the bed, where a suitcase lay open. Joel could hear the rasping chords from the man’s thin chest as he fought for breath. When he reached the bed, the man collapsed, gasping, on to the yellow candlewick bedspread.

Frederick Cummings had been an officer in the Tank Corps in the Great War. Wounded in France, he had been picked up by field ambulance and brought back to England to Bristol’s Beaufort War Hospital. After a slow recovery he was allowed home to his South Downs home to be taken care of by his beloved wife, Madelaine. He was then in his middle thirties.

Madelaine died after a lingering illness in December 1943. Fred had entered the Yew Trees Nursing Home a week ago. Opened only months previously, it was named for the huge yews that sheltered the Georgian building. With up-to-date amenities and the latest in comfortable beds, furniture, furnishings and nursing methods, the owners prided themselves on their modern thinking, calling everyone by their Christian names.

He paid eight pounds a week for the privilege of being well looked after. He had just asked Joel to bring him the small cardboard suitcase from the locker room, which contained a few of his personal belongings, including a photograph of Madelaine.

Joel knew that without Margaret Hill opening her first Care Home for Aged War Victims recently, he wouldn’t have a job, and Fred, having no relatives, would have had to depend on friends and neighbours to care for him. Not easy, thought Joel when you were as cantankerous as Fred was supposed to be. Joel, unlike the rest of the carers, ignored Fred’s quick tongue. The man had given his health for his country, and Joel respected that. But he still gave as good as he got with Fred’s barbs and despite being advised not to, had already formed a friendship with him.

Joel stared at Fred’s wrongly buttoned shirt that made the unattached collar look as though the studs weren’t doing their job properly. He didn’t offer any help. It would be more than his life was worth to tell the man he couldn’t even button his own clothing. In a moment the collar would be removed anyway, because it was time for bed.

He stood patiently while Fred, his breath restored, searched the case then triumphantly held aloft the silver frame.

‘Look at this, young shaver. This is a woman in the prime of her life. Put it over there opposite the bed where I can see it.’ The words almost sapped Fred of his strength.

Joel waited until Fred had stopped gazing lovingly at the picture before he took the frame and placed it next to the clock on Fred’s bedside table. For one swift moment the sepia photograph made him think of the girl from the Dog and Duck. Maybe it was the way the woman had her dark hair pinned back, from which tendrils escaped to frame her oval face. Mostly, the barmaid wore her dark locks swirling around her shoulders, sometimes in a coil of plaits that crossed over on the top of her head, like that skating star Sonja Henie, who was now a Hollywood film star. Whichever way she chose to style it, the girl’s hair didn’t detract from her prettiness. Neither did her pregnancy, come to that. He checked the time on the alarm clock that Fred didn’t need as the home ran like clockwork but that he insisted be left there, and which his arthritic fingers had difficulty winding nightly. Joel had volunteered to wind the clock but had received a look from the old man that could freeze hell over, and had never repeated the offer.

Joel caught sight of himself in Fred’s wall mirror. He ran a hand through his blond hair, which had tumbled down over his forehead. His shoulders were broad and his waist narrow.

He’d done a stint in the army himself, in the Royal Army Medical Corps, until an exploding shell had robbed him of part of his hearing very early on in the war, and ended his career fighting for his country.

His cap badge had stated In Arduis Fidelis and ‘faithful in adversity’ had certainly helped him obtain his job at Yew Trees. Here, inmates could well afford nursing care, their own rooms, full board and all the facilities they might have had at home, including a communal sitting room with a wireless, books, comfortable chairs, daily papers and jigsaw puzzles. On the sitting room wall was a large framed photograph of the manager, his wife, the cook Marie, head carer Pete, and indeed all the care workers and domestic staff. The manager intended to have photographs taken each year and put on display in the long hallway. Joel, having begun work at Yew Trees after the first photograph had been taken, hoped to be in the next one. He’d studied the print and noted four of the staff had already left.

Yew Trees comprised twenty-four rooms of male and female patients, staffed by strong and healthy workers, many with previous medical training. Kindness and a sense of humour were also necessary requirements. Joel sometimes worked a night shift, not minding the long hours. He lived alone and valued his independence, so he didn’t live-in like some of the staff.

When the wind sent fresh, salty air across the large, flowering gardens, patients could enjoy the sea breezes from Lyme Regis. Those residents needed to be well enough to either walk or be wheeled to sit outside in the sun. A pergola with seats and cushions gave shade. Fred had been outside this afternoon, reading his beloved Westerns and dipping Nice biscuits into endless cups of tea.

‘You want me to give you a bath?’ There were showers in the bathrooms down the hall but Fred couldn’t be bothered with the newfangled things.

‘No, I don’t. When I can’t bathe myself, I’ll be six feet under. And I can run it myself.’ He stopped talking to take a few deep breaths.

‘Don’t let the water rise above five inches.’ All the baths had lines marked on the enamel. Because of the war even water had to be rationed.

‘I’m not daft. Just old!’

Joel left him to it, taking the suitcase so he could put it back in the locker room later. He could depend on Fred to get to the bathroom, in his own time. Independence was important to Fred. Joel knew he didn’t want to be reminded that Yew Trees was the place he’d come to die. All the same, while Fred was in the bathroom, Joel would be waiting outside, keeping an unobtrusive eye on him. He would also remake the old man’s bed.

After Joel had placed Fred’s clean pyjamas on the bathroom chair and made sure fluffy towels were within reach, he let the old man get on with it.

‘Where’s your family, lad?’ The sound of water running into the bath diluted Fred’s words.

‘I’m like you, a loner.’

Joel thought of the girl from the pub and wished he wasn’t so alone. He thought of Fred’s photograph of his wife that meant so much to him. ‘Memories keep us sane,’ he called back.

‘Give us a hand, lad.’

Joel knew the old man had had to summon up courage to admit he couldn’t quite make the step into the bath. He went in, trying not to look at the skinny misshapen body with its genitals wrinkled and hanging like dried tree fruit, and swirled his hand into the wetness, checking cold had softened the effect of the scalding water. Joel stood so the man could use him as a stepping stone into the bath. When Fred was sitting, like a large thin baby, Joel left. He could now change the bedding so Fred could feel refreshed in bed as well as clean.

In room eight he stripped the sheets, ignoring the marks of Fred’s incontinence. He wasn’t as bad as some of the inmates.

In room twelve the old lady hardly ever left her bed. The resident doctor, Dr Barnaby, saw her twice a day and she was hard work to look after. Her name was Liliah but woe betide any of the nursing staff who tried to befriend her or shorten her name.

In the short time the home had been open, one helper assigned to Liliah had already handed in her notice. Management decreed staff should use their own discretion in the way they approached their charges. Sometimes it was impossible to be on good terms. Sometimes a laugh, a joke, or a sympathetic attitude helped the trust between carer and patient. Joel’s army training had been rigorous. Being in the medical corps had undoubtedly helped, but he was by nature a caring man.

With the room tidied, Joel swept up the dirty washing and then left it in the canvas container ready for removal to the washroom. His thoughts were broken by Fred’s voice.

‘Boy!’

‘The name’s Joel,’ said Joel, back in the bathroom. There were no locks on the doors and once he had Fred standing securely, he handed him the large bath towel. Fred had used soap to wash his hair and it stood to attention.

‘I need a hand to get back to bed.’

The striped pyjamas didn’t take Fred as long to get into as Joel thought they might; Fred was beginning to trust him. But he made a mental note to obtain a wheelchair – the old man wasn’t as sprightly as he thought he was.

Fred saw the tidy room and bed. ‘Didn’t ask you to do that,’ he growled.

‘I know,’ Joel said, sitting Fred upon the counterpane. ‘And if there’s anything else you don’t want me to do, just ask.’ He helped the old man into bed. In a short while the nurse would be round with Fred’s medication.

Soon, Joel would be off duty, so he made his way downstairs.

In the large kitchen, Pete was reading, his feet high on a stool and a mug of tea at his elbow. Marie was making sandwiches for staff supper. The delicious smell of beef stew was cooking, more stew than beef. There was, after all, a war on. But tomorrow’s dinner was assured. Next to the apple crumble, fragrant and already cooked and left covered on the side, a sponge cake was cooling, waiting for its jam filling. All the residents enjoyed Marie’s sponge cakes, which she made when she had the ingredients to bake them.

‘All quiet,’ said Joel. He pulled out a chair and sat down at the table.

Marie looked up from the Spam she was slicing thinly. Plump and rosy cheeked, her greying hair a bubble of curls, she said, ‘Thank Christ for that.’

Pete said ‘Liliah’s been acting up. Earlier this evening she wouldn’t stop crying about people stealing from her. And she was remembering her husband being blown up in the Dominium Theatre disaster. During the Blitz, that was,’ Pete said, without looking up. ‘That was the start of her turning funny.’

Marie said, ‘She was an ambulance driver, apparently. Found her husband amongst the soldiers home on leave there.’ She slapped slivers of meat between the slices of bread. ‘Only just recognizable, he was, and she had to attend to him.’

‘What a dreadful . . .’ Joel suddenly realized Liliah couldn’t be as old as he believed she was. ‘I thought she was in her sixties?’

‘No! An incendiary bomb hit the ambulance, didn’t kill her, but it might as well have. She’s barely forty, maybe not even that. She never properly recovered from the head wound. No other relatives, no kids. Sometimes she’s lucid. It doesn’t last. Then she starts imagining stuff, like people taking things from her,’ Pete broke in.

‘That’s so sad,’ Joel said. All his training had been about healing people and he hated it when he couldn’t be of use to anyone. ‘This bloody war,’ he said, drumming his fingers on the table top.

Pete didn’t have sole charge of Liliah. Although Joel wished more people would apply to work as carers, he knew it took a special type of person willing to clean up after the sick and elderly, especially when . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...