- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

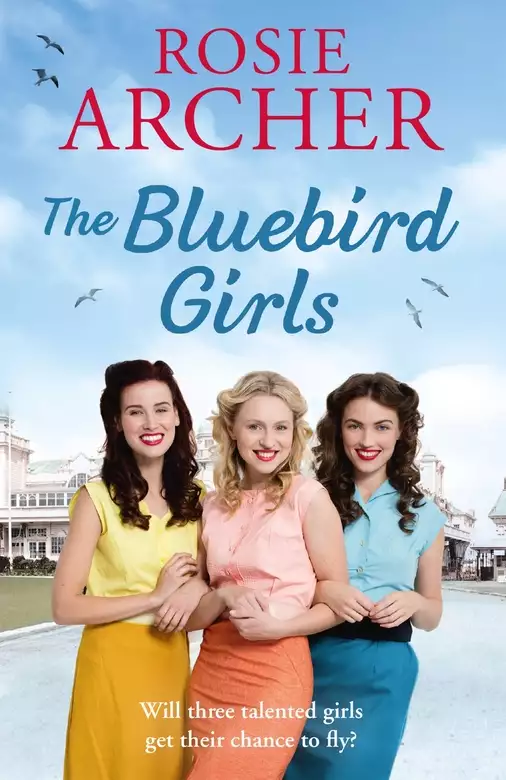

Synopsis

Rainey Bird, Ivy Sparrow and Bea Herron all love to sing. For Rainey, music has been a solace during the upheaval of starting a new life with her mother, away from her abusive dad. Bea finds a confidence when she sings that she cannot get from anything else. Ivy sees it as her best chance of making a life away from Gosport and a dead-end job. The three of them sing in a choir run by the strict but kind Mrs Wilkes. When war breaks out, though, dreams must be put on hold. That is, until a mysterious stranger arrives with a proposition that just might change their lives...

Release date: January 10, 2019

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 260

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Bluebird Girls

Rosie Archer

‘Would you call this a moonlight flit?’ Josie Bird’s sixteen-year-old daughter Lorraine had stopped singing long enough to ask her the question.

The answer came easily. ‘We’ve got moonlight, our personal possessions are piled high around us and our gas masks are stowed beneath the seats. Hopefully not one nosy neighbour watched us leave.’ Jo stole a glance and smiled fondly at Rainey. ‘Yes, we’re doing a flit.’

‘Not before time.’

Jo’s heart constricted at the bitterness in her voice. No mother should have to listen to her daughter speak like that.

The late October wind was trying to iron out Rainey’s auburn curls so she used her hands to clamp her hair from blowing into her eyes. Jo had urged her to tie on a headscarf as she had done but Rainey had raised her eyes heavenwards and muttered, ‘Aw, Mum!’ The open-top MG PA Midget gave no protection from the elements as Jo was unable to raise the hood due to their overflowing belongings.

‘Oh!’ Turning the steering wheel briskly to round the corner onto the Gosport road caused Jo to cry out. Her shoulder reminded her it hadn’t yet properly healed. She bit her lip in an effort to ignore the sudden pain.

‘You all right, Mum?’

Her husband Alfie had wrenched her arm almost to the back of her neck and she’d been unable to use it for some time. ‘Yes, I’m fine. It won’t be long and we’ll soon be in our new home.’ She was changing the subject, as usual. She didn’t want to think about the final beating she’d been subjected to. It had made her decide to visit estate agents to investigate cheap housing to let.

She’d struck lucky because people who could afford to leave Gosport had gone to escape the inevitable bombing from Hitler’s aircraft after the recent declaration of war against Germany. She would have preferred somewhere a bit further from Portsmouth, in case Alfie came looking for her, but beggars couldn’t be choosers.

The unfurnished house she had taken was in Albert Street. Her meagre savings had been practically used up on the deposit and the first week’s rent. Jo had returned to London Road in Portsmouth, excited at what might be her and her daughter’s new start away from her bully of a husband.

The car spluttered.

‘Oh, no!’ Jo’s heart plummeted.

‘Is it out of petrol?’

‘Probably,’ replied Jo. The fuel tank’s needle pointed to full, but it had been in that position since the day Alfie had driven the carmine-red vehicle home from the barracks after winning it in a poker game.

‘Present for you,’ he’d said, lifting her off her feet and swinging her around. It was 1936 and he’d wanted her to believe he loved her then. Perhaps he’d thought the gift of the car would soften her feelings towards him after she’d discovered his affair with Janice Woolbetter. Every so often she pumped petrol into the car’s tank, but the needle never moved.

Jo had remembered her own and Rainey’s ration books and identity cards, but in her haste to get away she’d forgotten the petrol coupons that controlled fuel rationing. When bought from Morris Garages in 1935 the car had cost somewhere in the region of two hundred pounds, so she’d been told. Jo intended the two-seater should be stored in the shed at the side of the new rented house as security for the future.

‘It seems all right now,’ Rainey said. The engine sounded fine once more. She grinned as Jo stole a look at her, then began singing again.

Jo breathed a sigh of relief when she saw the Criterion Cinema ahead: they were almost at their destination. By the light of the moon she could just make out the film advertised on the billboards. It was Dead End with Humphrey Bogart and Sylvia Sidney. She wouldn’t mind seeing that, if she could afford it.

A job for herself was first on the agenda, and Rainey needed to return to a school as soon as possible. She’d been doing well at Portsmouth Academy where she’d excelled at typing and shorthand, but leaving Portsmouth meant that she hadn’t completed the course.

‘Not much further,’ Jo said, but she might as well not have bothered because Rainey couldn’t possibly hear her. She was giving full voice to ‘The Biggest Aspidistra in the World’, her rendition just as hearty as Gracie Fields’s version. Jo smiled. It made her heart happy to hear her daughter singing.

And then ahead, off Forton Road, was Albert Street. Jo gave a hand signal and turned right into the terraced street.

‘Which one is it?’

‘Number fourteen, the one with the wide shed. Thank God we’re here.’ Jo pulled up outside the front door that would open straight onto the pavement. Within moments she had the key in the lock but allowed Rainey to enter first. ‘Don’t put any lights on,’ she warned. ‘Remember the blackout. I don’t think there are curtains at the windows. Let’s just take everything inside the house so I can put the car away from prying eyes.’

‘Mum, stop worrying. There’s nobody about. It’s as quiet as the grave.’

Rainey was right. The little street that led down to the railway footbridge and goods yard was deserted, but Jo knew she wouldn’t begin to feel safe until the car was locked away and she and her daughter were inside the house with the door shut.

‘It smells a bit funny in here,’ Rainey said, dumping the brown carrier bag that had been on her lap the entire journey.

‘It’s only a bit of damp. Don’t worry about it.’ Jo put down an armful of rolled-up blankets on a broken chair. She fished out a torch from her coat pocket and gave a quick flick of light around the place. It was even more dismal than she’d remembered. She tried to imagine the small dank room with bright rugs covering the second-hand furniture she would buy when she could. ‘We’ll soon make it nice and homely,’ she said, trying to reassure herself as well as Rainey.

Rainey gave a big yawn, then shivered.

Jo said, ‘I’m tired and cold as well. C’mon, the sooner we get the stuff indoors the sooner we can have some cocoa from the flask and set about making up a bed for the night.’

She hadn’t told Rainey they’d have to sleep on the floor. She didn’t want to think about mice or creepy-crawlies.

Soon everything they’d brought with them was piled in the living room and Jo had cleared a space in the shed for the car. When she got back into the house she discovered Rainey had hooked a blanket over the front window, found the candles, lit one and was making a nest of bedding on the bare boards.

‘I had a look upstairs, Mum. There’s a mattress on the floor in the back bedroom but I didn’t want to risk it. It might be full of fleas.’ Rainey made a face. ‘I’m so cold even the candle seems to give out heat,’ she said. ‘I’m not getting undressed – it’s freezing.’

Jo put her arms around her daughter. Tears burned the backs of her eyes. ‘I’m sorry I’ve taken you away from a nice home and brought you here.’

She didn’t get any further as Rainey cuddled into her. ‘I wanted to leave as well, don’t you ever forget that. If we hadn’t got away tonight, sooner or later he’d have killed you, and I need my mum.’

Chapter Two

Corporal Alfie Bird didn’t want to leave the Royal Army Ordnance Corps Barracks at Hilsea to fight in France. He hadn’t wanted to return home on a forty-eight-hour pass to find his wife and daughter gone, either.

All he’d done was push Jo around a bit for shooting her mouth off about him and Janice. Jo knew how upset he got when she tried to best him in an argument. It was her own fault. He sniffed and wiped a hand across his red moustache, remembering.

‘I saw you this afternoon walking arm in arm with Janice Woolbetter in Elm Grove.’

She’d come straight out with it, no messing about.

‘Oh, yeah? Would that be while I was overseeing weapon repairs in the stores all day in barracks?’

She’d ignored his lie. ‘I was on the bus. She was laughing up at you in the rain.’

‘You’re mistaken. It wasn’t me.’

‘You promised me it was over between you and her.’

He’d begun to lose his temper but he’d kept it in check long enough to say, ‘If it was raining I doubt you could tell who was with the bloody woman.’

‘I recognized you,’ Jo insisted.

He’d tried to sweet-talk her then. ‘When I broke it off with her, I promised you that was the end of it.’ Then he wheedled, ‘I told you, you’re the only woman for me.’ He tried to put his hand on her shoulder. A little bit of comfort never hurt anyone, he thought. Jo had flinched, stepping away, standing where she’d thought he couldn’t reach her and staring into his eyes, all defiant like.

‘It was you, with … her,’ Jo insisted, hissing ‘her’ like she’d found shit on the sole of her shoe.

He’d lashed out then.

Had her pinned against the wall, her face pressed into the wallpaper, her arm behind her back. ‘You didn’t see me,’ he yelled. He pulled her arm higher.

But the bitch wouldn’t give in. ‘I did.’

Her voice was so small he barely heard her. Still holding her arm he twisted her away from the wall and threw her into the centre of the living room. Stupid woman lost her footing and fell. She hit the corner of a wooden chair, it toppled and she fell on the floor. She cried for a bit, then didn’t make any more sounds, just lay there. She was obviously messing about, pretending, so he kicked her a couple of times, then slammed out of the house before he really lost his temper.

He’d walked up to Hilsea Lido and sat on a bench in the park. It was growing dark. He looked at his watch. As usual, Rainey would be round her friend Ellen’s house but she’d be going home soon. She’d see to her mother, if Jo needed seeing to, that was. She was probably up off the floor by now, a cuppa in her hands. Why had she been so determined to rile him?

Of course he’d been with Janice. What bloke wouldn’t prefer to spend the morning in bed with a plump warm blonde, then take her out to a café for something to eat? It beat going home to a stringy wife, who never believed a word he said, and looked as though she’d rather be anywhere than with him.

What if he had gone back on his word never to see Janice again? Didn’t a man have the right to do what he wanted? After all, he’d spent ten years as an enlisted soldier. He provided a home for his wife and daughter and saw they were clothed and fed. Jo had known he had a quick temper when she first went with him. Fifteen she’d been, younger than Rainey was now. He’d knocked that silly young bloke for six after he’d caught her dancing with him at the Savoy Ballroom. Told her then if he took her to a dance she stayed with him all evening. She didn’t dance with the first bloke who asked her just because he’d left her on her own while he went to the bar.

A few months later he’d got her in the family way. She was sixteen and looked like an angel at the register office.

A lot of water had run under the bridge since then. Oh, it was fine at first, lots of loving and laughs, but that changed after Rainey was born. Jo started moaning about feeling tired. Said it was the baby crying all the time. Well, he couldn’t do nothing about that when he was in barracks, could he? When he was on leave she only expected him to get up at nights and see to Rainey! He’d told her it was woman’s work. What did Jo expect? She’d have him in an apron next.

He was able to play the field a bit when he was sent away on military training. What Jo didn’t know couldn’t hurt her, could it?

At the RAOC barracks at Hilsea he couldn’t carry on like before but Janice was special. Until a ‘friend’ told Jo. He hadn’t laid a finger on Jo until then, well, not really. All that rubbish about her being afraid to trust him got on his nerves. Time and time again he’d warned her to stop but she wouldn’t, so it was her own fault when he lost his temper. Everyone knows it ain’t easy to keep a temper in check when a wife nags.

At the hospital she said she’d fallen down the stairs. After she came home she seemed to have lost her spark. She was no fun any more. Janice made him laugh, though.

Of course, Janice wasn’t the only one. The years and the women came and went, but Janice was always up for it.

Money wasn’t a problem. He had a crafty bit of trickery going on in the stores so Rainey didn’t need to leave school to find work. She could stay on and make something of her life, become a typist, perhaps, or a private secretary.

Why, oh, why had he suggested he and Janice walk along Elm Grove in the rain to the café?

By what quirk of Fate had Jo been nosing out of the window of the bus at that exact moment?

And now had come the bombshell that he was to be shipped to France.

The British Expeditionary Force had already left, and more men were to follow. The Royal Oak had been torpedoed in her home base at Scapa Flow. Eight hundred men had gone down and all because of that clown Hitler.

He’d come home today to tell Jo, only to discover the bitch had left him, taking his daughter with her. Just wait until he got his hands on her, he thought. Then she’d know what pain was.

Chapter Three

Rainey pulled the corner of the blanket over her nose. It wasn’t the damp, or the strange noises that sounded like small creatures going about their business in the darkness of the little house, that was keeping her awake. Even the hardness of the floor didn’t matter. It was the smell of dirt. Filth left by other people. And it was her fault they were there, lying in it.

Her mother, curled up beside her, was breathing softly. Rainey wondered if she was asleep. She hoped so. She would have liked to touch her, for comfort, but didn’t want to disturb her.

She thought back to the day she’d arrived home to discover her mother lying on the floor. She’d looked as if she was asleep, but she couldn’t possibly sleep with her foot at that strange angle near the upturned kitchen chair – and why would she want to?

‘Mum! Mum!’ Rainey had fallen on her knees beside her mother. Her shrill voice must have disturbed something behind those serene features because her mother had opened her green eyes and immediately tried to rise. Pain had crossed her face. Rainey saw how she’d tried to use her right hand to push herself up from the floor, but her arm had buckled and she’d pitched forward on it.

‘Is it broken?’ Rainey put her arms around her mother and propped her into a sitting position. Jo had managed to make a loose fist. Rainey could see it took a painful effort.

‘I don’t think so. But my arm doesn’t seem to do what I want it to.’ Her mother used her other hand to massage her right shoulder. ‘Put the kettle on, love,’ she said wearily. ‘I need a cup of tea.’

Rainey stood up and stared down at her mother. ‘He did this, didn’t he?’ Without waiting for an answer she added, ‘I should get you to the hospital.’

‘No! The last time they asked so many questions . . .’

Rainey looked at her in disgust.

In the scullery, Rainey shook the kettle and, satisfied there was enough water in it, lit the gas. Anger was consuming her. She thought of Ellen. Her friend and her younger brother had been playing Cowboys and Indians with their father while their mother was at the market. When she’d closed their front door to come home, she was still smiling at the sight of Ellen’s dad lying on the floor tied up with bits of string as the ‘hostage’ caught by seven-year-old Tommy.

She could neither remember nor imagine her own father making a happy spectacle of himself like that. But, then, her father wasn’t home a great deal and she hated it when he was. Immediately he set foot inside the house a big black fog seemed to settle over everyone. She even thought twice about singing when he was around and she loved to sing.

‘I’m not stupid, you know.’ Rainey pushed open the kitchen door and looked at her mother, who’d managed somehow to settle herself in the armchair. ‘This is just the latest of the many times he’s taken his temper out on you. We have to leave.’

She saw the tears spring to her mother’s eyes and waited for the usual protestations, but instead she heard her say quietly, ‘I know. But I shouldn’t have goaded him.’

Rainey didn’t ask questions. Ellen had confessed to overhearing her parents whisper about Alfie Bird and ‘that blonde’ being spotted in a pub. Her mother must have discovered he was once again entangled with that Janice he couldn’t seem to let go of.

The sad thing was her mother still loved him. She had since she was a girl and now, after taking all Rainey’s father had dished out over the years, she hadn’t the confidence to leave him. But if she didn’t . . . Rainey didn’t want to think about the consequences and, even, life without her beloved mother.

At sixteen, Rainey was old enough to leave school and get a job but her parents wanted more for her. If she left Portsmouth she could return to school in another place, couldn’t she? Her mother wouldn’t like her to throw away her education. But Rainey could perhaps get a part-time job and her mother would be able to go out to work, like she’d always wanted. Her father had decided early on that Jo’s place was in the home. But they’d need to earn money if they left this house. If only she could persuade her mother to leave.

She watched her mother splay her fingers, saw the agony on her face as she moved her arm. Rainey sighed. Jo might have lost confidence in herself but Rainey had enough for the two of them. The kettle began to whistle. Rainey went back into the scullery and began making tea.

‘I should get the doctor to see you,’ she called. As the words left her mouth she knew if her mother could stand upright she would sweep away all Rainey’s suggestions. She’d certainly never tell anyone that Alfie Bird knocked her about. Rainey remembered the time her mother had been taken to hospital. She’d not disclosed the truth: she’d lied to save Alfie’s reputation.

‘But nothing’s broken. It’ll soon get better. I really should watch where I’m going. Fell over that damn chair . . .’

There she goes again, thought Rainey. Already she’s forgotten she’s admitted Dad hit her. Now she’s pretending it never happened.

Rainey slammed the teapot down on the table, causing the lid to jiggle and hot tea to spurt from the spout. With the cups in her hands she went into the living room.

Her mother obviously hadn’t expected her to enter so had her jumper pulled up and was examining dark red marks blooming over her ribs. Rainey almost dropped the cups at the sight of the bruising. After putting them on the table she fell on her knees in front of her mother. ‘Oh, Mum, we have to get away.’ She eased Jo’s jumper down, then pushed back the fair hair that had fallen across her mother’s face, tucking it behind her ear. She looked into her eyes. ‘If we tell no one where we’re going, we can build a new, happier life.’

‘But what about your friends, school?’

Rainey clutched her mother’s left hand. She wanted to say, ‘I’d miss them but sooner or later I have to escape into the big wide world and I’d rather do it with you beside me,’ but instead she said, ‘I can go somewhere else to carry on studying, if that’s what you want for me.’ She paused. ‘We could both get jobs . . .’ She’d stared into her mother’s tear-stained face. ‘Please?’

And that had been the start of it.

She’d urged her mother to find them a place to live. That hadn’t happened straight away because her mother’s shoulder had taken a while to mend sufficiently for her to gain control of her arm and hand.

Now Rainey shivered again. It was so cold in the stinking room. She looked across at the big black range. Tomorrow after they’d cleaned it they could see if it worked. That should warm the place. Light from the torch and later a dim candle had shown up bits of broken furniture they could burn.

It was a pity they’d had to leave so much nice stuff behind but the small car had been loaded to the gills as it was.

Her father would never find them here.

Into her head came the words of ‘With a Smile and a Song’. She’d gone to see the picture Snow White with Ellen and they’d sung that tune as they’d walked home together, arm in arm. In her mind, the music played. At the pictures all the films ended happily. Her life and her mum’s might not be like a film but she’d try her hardest to make sure there was happiness ahead.

One thing she was sure of: she’d never let any man treat her the way her mother had been treated.

Chapter Four

‘Thanks, Mrs Perry. That’s you paid up until the end of November.’ Jo ticked off the money owed and wrote down in the ledger the final amo. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...