The Edinburgh Murders

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Series info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Helen leaned close enough to fog the mirror with her breath and whispered, 'You, my girl, are a qualified medical almoner and at eight o'clock tomorrow morning you will be on the front line of the National Health Service of Scotland.' Her eyes looked huge and scared. 'So take a shake to yourself!''

Edinburgh, 1948. Helen Crowther leaves a crowded tenement home for her very own office in a doctor's surgery. Upstart, ungrateful, out of your depth - the words of disapproval come at her from everywhere but she's determined to take her chance and play her part.

She's barely begun when she stumbles over a murder and learns that, in this most respectable of cities, no one will fight for justice at the risk of scandal. As Helen resolves to find a killer, she's propelled into a darker world than she knew existed, hardscrabble as her own can be. Disapproval is the least of her worries now.

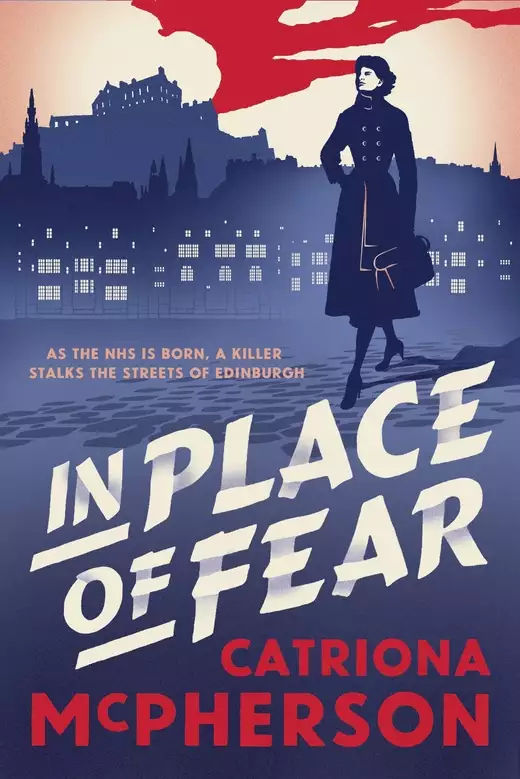

IN PLACE OF FEAR is a gripping new historical crime novel that is both enthralling and entertaining, and perfect for fans of AJ Pearce and Nicola Upson.

Release date: April 10, 2025

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Edinburgh Murders

Catriona McPherson

Chapter 1

‘I like a guid hard scrub,’ Mrs Hogg said for the umpteenth time. ‘Dinnae be tickling me.’

Helen Crowther stuck her bottom lip out and blew upwards, trying to lift the damp tendrils of hair plastered to her sweating forehead. She wasn’t about to touch her face with the hands she was using to wash Mrs Hogg’s back.

She still wasn’t sure how she’d ended up washing any bit of the woman. She’d only offered to chum along and glare at the baths attendants if they got nippy.

‘You wouldnae ken, whip like you,’ Mrs Hogg had said, tears standing in her tiny, curranty eyes. ‘They can be very cutting at that Cally Crescent. Airs and graces.’

Helen believed her. Everyone had just seen what a smidge of power could do to the wrong kind of person. There was a black-out warden from Lochrin who’d have had the city’s population in chains for a glowing fag end. And Helen had spent every Friday night at Cally Crescent herself, from the day she got too big for the zinc bath on the kitchen floor to the day she moved into her wee palace with its own doings. Mrs Hogg was right; Helen had never been scolded for the reason she’d been scolded, but she’d heard plenty about getting the free towel too wet, or soaking for too much of the half hour folk were entitled to, or using too much of the chip of carbolic that had been paid for.

‘You should give Mrs Hogg a penny off if anything,’ Helen had told the attendant who’d muttered and grumbled them upstairs and into a cubicle.

‘Aye!’ Mrs Hogg chimed in, pugnacious in advance of the insults she was expecting. ‘I’ll save water for you. I’m like a brick in a cistern, me.’

She was more like a cork in a bottle, Helen thought to herself as she tried to squeeze the back brush in along the woman’s side to wash her oxters.

‘Oh!’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘Lovely! Scrape away, Nelly. I like to step out of ma bath rid raw.’

Helen scraped, and kept her eyes trained upwards on the tiles of the cubicle, tracing imagined pictures in the dark veins on the green ones, wondering why on earth the others were mustard-yellow and cream, instead of a nice clean colour like blue or white, or even pink. None of that had occurred to her back when she used to lie here in her own steamy water but, now she was a householder who chose distemper and curtain fabric, she cared about such things.

‘Aye well,’ said Mrs Hogg presently, with a sigh, ‘my time’s near up and I need to leave plenty.’ At least she had brought her own sheet from home to wrap up in. The towels you got with the one and thruppenny baths wouldn’t have gone near her. Helen held it up above her head and out as wide as her arms would go to give the woman her privacy, praying she’d get her leg over the side and not slip.

When Mrs Hogg was standing safely on the wooden rack that did for a bathmat and kept the bathers’ clean feet off the clarty floor, there wasn’t a lot of space for both women in the cubicle, so Helen edged round the door and said she’d stay in earshot in case Mrs Hogg needed a hand with—

‘Ma nooks and crannies!’ It wasn’t quite a shout but the acoustics in the tiled alcoves made the most of it anyway. ‘Ah’ve got a system,’ she assured Helen, who let the cubicle door fall shut and stepped away before she could be given any details.

It was cooler out on the balcony, fresher too, and Helen had always liked the view from here: the filigree-patterned iron that held the roof and the way the light bounced off the shiny tiles. They were spanking clean, wrong colour or no.

Below the balcony, the swimming pond was crowded with children, splashing and shoving, so many of them that the pool looked like a good pot of bairn soup. Helen shuddered. She’d not go near that water till Monday at least. There was bound to be a fair few of those boys and girls getting clean with a tuppenny swim instead of a nine-penny

soak. The Downie family had done it themselves more than once when her mammy was on short wages in the bottling hall, those tight years after the first war if her daddy’s pay packet wouldn’t stretch to the four of them.

Above the weans bobbing around in the water but below the folk like Helen leaning on the balcony rail, were the acrobats. They weren’t really acrobats, not from a circus or anything. They were just local laddies, but they were swinging on rings that hung over the pool, making their way up and down its length, showing off to the lasses watching in wonder. Helen remembered the days when she would have marvelled at them too: the strength it took, the confidence, the courage needed to step off the platform high above the deep end and grab for the first ring, risking a soaking if you missed it. Now all they made her think of was chimpanzees in a jungle. ‘Don’t get sour, Nelly,’ she told herself. ‘It’s harmless fun.’

But she looked away anyway. She didn’t want to be seen gawking at laddies in their simmets, an old married woman of twenty-seven like her who should know better. Besides, she had noticed something on the far side of the balcony that snagged her attention and made her smile. Someone in one of the cubicles had thrown his towel over the door, just like her father always did and just like her mother always gave him wrong for: letting all and sundry see their towels! Showing the world their business! Helen knew what lay behind the scolding. Greet had once caught a neighbour rubbing a piece of the terrycloth between thumb and finger and overheard the verdict: ‘You could spit peas through this. Your Mack’ll have to stand by the fire when he gets home or he’ll be chittering.’

Helen’s mammy had that perfectly good towel cut up for rags before bedtime. Helen could remember Greet sitting hemming the squares as if she was sticking pins in Mrs Suttie with every stitch and she was round at the store draper at opening time Saturday morning ordering new.

The towel across the balcony had disappeared when Helen glanced back. Whoever it was was getting dried now. She saw a hand and a forearm above the door, pumping up and down as the vigour needed for drying off in all this steam got underway. She stared and then she squinted. That was ten times worse than watching a set of laddies who were only swinging about to be watched anyway, but Helen couldn’t drag her eyes off what she could see above the cubicle door over on the south side. That wasn’t another man who had slung his towel over the door, like Helen’s daddy. That was Helen’s daddy. That was Mack’s hand, his arm. That was his head, tousled from rubbing his hair dry, his dark curls just like her sister Teenie’s, until he put on his hair oil and combed it flat again.

But why was Mack in the Cally Crescent Baths? Ever since Helen had moved into her house a year past summer, the whole Downie clan came round on a Friday to revel in luxury and then sit by her fire with

fish and chips. And, even before that, even on the right night, Mack had never had his bath this early. Helen glanced at the clock, steamed up and never quite telling the true time, on the short end of the balcony. Below it, the windows of the attendants’ wee howff were muffled with eternally damp, grey-ish muslin so no one out here could ever tell whether someone in there was watching. Until, that is, one of them swept the door open and came stamping out to threaten the bathers with extra charges for ‘going over’. One of them was at it now. A thin, crooked man in a white overall and rubber-soled shoes that squeaked like tortured mice on the balcony floor was making his way up the south side peering at the chalked times on the outside of the men’s doors and consulting his pocket-watch over and over again, as if the time might have changed more than a second in the second since he’d last looked.

‘Give a small man a bit of power right enough,’ Helen muttered to herself.

Her daddy – if it really was her daddy – clearly had some minutes left in his half-hour slot, since the attendant went by that cubicle without stopping. At the very next door though, he swiped the chalk away with the heel of his hand and then, making a fist, battered so hard on the painted panels that the children in the swimming pond below all looked up, the single movement of their many heads making Helen think of swallows turning in the summer sky. One of the acrobats, startled, let go of a ring mid-swing and was left dangling by one hand.

The only one not to react at all, it seemed, was the man behind the door.

‘Ho!’ the attendant called out, a boom of a sound intended to rise above the splashes and shouts. ‘You’ve one minute to get oot or Ah’m coming in!’

With another last glance at his watch, he stalked back to his bothy and slammed the door, making the grey muslin swing once or twice before it settled.

‘Somebody in bother?’ said Mrs Hogg, appearing beside Helen. She was puffing and panting, rivulets of sweat already beginning to trickle down the sides of her face, minutes after her wash. She fanned the neck of the capacious housedress she had dropped over her head and settled herself against the balcony railings, spreading her drying sheet out along the banister for all the world as if it was the pulley in her own kitchen.

‘Thon wee crooked mannie’s forgot to do a warning,’ Helen told her. ‘That’s what I reckon. He’s found somebody past time and he’s taking it out on them.’

‘Forgot to do a warning?’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘Away! That’s the only thing that lets them thole this job, Nellie. Getting to shout and stamp at folk for spinning out a soak. Bar that, it’s all picking hair out drains and sweeping up toenails.’

‘You’ve a right way with words, Mrs Hogg. I never thought on the hair in the drains till this

minute. Boak!’

‘Aye-aye,’ said Mrs Hogg, nudging Helen. ‘Here he comes again.’

The same attendant, taking a strict view of how long a minute lasted, was marching along the balcony, watch in hand and jaw off-set as though he was grinding his teeth.

‘What a state to get in,’ Helen said. ‘Even on the busiest night. Mercy! He’s unlocking the door. Oh don’t look. The poor man!’

She turned away, loath to see a stranger climbing naked out of a bath, but Mrs Hogg leaned over the railings for a better view. ‘Seen one, seen them all,’ she said. ‘But it does no harm to check, eh?’

‘Speak for yourself,’ Helen said. She’d never seen even one, and wasn’t keen to start tonight.

‘Nelly,’ said Mrs Hogg, nudging again, in the back this time.

‘Leave me be!’ Helen said, but she softened it with a chuckle. She liked Mrs Hogg, coarse as a deck brush though she was.

‘No, Nelly,’ she said again, taking hold of Helen’s arm and trying to turn her. Helen spread her feet wide and resisted. ‘There’s something wrong,’ Mrs Hogg said, the quietest she’d been throughout the entire outing. ‘Something’s no right over there. Look.’

Helen turned, still half expecting a trick and a loud shout of laughter, but Mrs Hogg wasn’t joking. Over on the far side of the balcony, the attendant was that minute stumbling backwards out of the open cubicle door. When he reached the edge of the balcony, he turned and his face was whiter than his overall, his lips trembling. He bent over the railings.

‘Dinnae you boak in that pond!’ Mrs Hogg shouted, her voice ringing out clear and hearty despite the muffling steam. ‘Dinnae you dare make a mess on all they weans!’

But he wasn’t sick. He was faint. As everyone watched, he pivoted on the polished balcony rail, threatening to topple then threatening to crumple until, with him losing consciousness completely, simple gravity took over and he plunged headfirst into the pool below him, hitting the water with a smack and causing a huge gout of water to rise and wash over the changing booths at the side. His pocket watch followed him down, making a small plop beside him.

‘No so bad then,’ Mrs Hogg said.

The children in the swimming pool were laughing fit to drown themselves and every adult around the edge at the changing neuks, or up on the balcony at the cubicles, was either trying not to laugh or doing it behind their hands.

‘Come on, Nelly,’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘Naeb’dy’s looking. Let’s see what’s to do.’

Chapter 2

Helen noticed the smell before the cubicle door was fully open. Of course, the baths were always known for smells. Whether Fountainbridge folk worked at the brewery, like Greet, or the distillery, tannery, dairies, stables, the sweetie factory – which few believed was worst of all until they’d spent a shift there – or – like Helen’s daddy – the abattoir, they were ready for a good wash by Thursday night. Then there was the carbolic, the thick, the pink floor soap, the drain bleach, whatever they put in the swimming pond and the foot bath, the never-dry mop heads, and the steamy damp rising off all the clothes hung on hooks to be shrugged back on again at the end of the night.

But this was something different. This smell didn’t belong at the baths, although it was familiar from somewhere. Helen felt recognition and, on its heels, her stomach lurched just as Mrs Hogg, crowding in behind her to peer over her shoulder, said, ‘Faugh! What’s that? That’s reeking. That’s turning my wame, Nelly.’

By then, sight had overtaken smell as it did a moment later for Mrs Hogg too, who fell back with a quiet ‘Oh!’, sounding quite unlike herself. For inside the little cubicle, through swirling steam, they could see a man not exactly floating on the surface of the water, but braced and bobbing, as if he had decided to halt halfway through leaping out when the attendant banged on the door. He wasn’t going to leap anywhere, though, no matter how hard anyone banged, no matter what the threat of humiliation. He was beyond embarrassment. He was beyond cares of any kind.

Later Helen would remember thinking his face was frozen, unaware of how wrong that impression would prove to be. Certainly, he wore a rictus of agony, his eyes and lips wide open and even his tongue seeming to arch like an eel in his mouth. His hands gripped the rolled edge of the bath and his feet were hard against the end panel so that his whole body was bent into an impossible shape. How his back didn’t break from such an angle, she couldn’t imagine.

‘Is he deid?’ said Mrs Hogg, still whispering.

‘He must be,’ Helen answered. She took one step inside and touched his arm. She didn’t expect it to be cold, not with him dying in his bath as he had done, but she must have thought it would be cooling. At any rate, it was a shock to find that it was hot under her fingertips. She took another step and laid a palm on his biceps. His whole arm was as hot as . . . Helen’s mind turned away from the thought that was forming, even as her eyes took in the blistered look of the skin on the front of his body, and the bright-red, smooth look of the bits of him still underwater, as angry and puffy as sunburn.

‘Here,’ said Mrs Hogg, nudging once more. ‘Poor wee mannie.’ She held a face flannel, her own, in her hand and nodded at the dead man’s midsection. Helen took the square of cloth and laid it gently over his hips for his dignity. There was something off about how it settled against his skin though. There was something off about every bit of this and again her mind revolted against the growing knowledge of what that thing was.

Still, she bent and dipped the tips of her fingers into the water, then snatched them back with a hiss.

‘What’s he died fae?’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘Hert, is it? Something sudden anyway.’

Helen couldn’t speak. She knew beyond her mind’s attempt to deny it that what had killed this man wasn’t sudden at all, and she didn’t understand what had kept him in his bath while it happened. Why would anyone lie in water as it got hotter and hotter?

Because that was what had happened. That poor man’s skin was as tight as the rind on a poached ham. That smell that didn’t belong in the baths? That smell

Helen knew so well – her, the daughter of a slaughterhouse man, brought up on cheap cuts carried home for her mammy to cook up into a stew? That smell was meat.

And the feeling of the flannel against his hips? Every cook knew not to cover skin too close or it would stick. Even his face made sense now, except that the look of his wide-open mouth and his arched tongue had been hidden with a roasted apple whenever Helen had seen it before.

‘Oh, Mrs Hogg,’ she said, whispering as weakly as had the other woman. ‘He’s boiled. That poor soul’s boiled like a pudding.’ Then, before she knew what she was doing, Helen barged past the other woman. If she’d been more spindly she’d have been knocked off balance, but as it was she barely rocked.

‘Daddy!’ Helen shouted, hammering on the next-along door. ‘Faither! Mack Downie! Tell me you’re out your bath. Stay out that water. Daddy, it’s Helen. Tell me you’re all right!’

The commotion from the fallen attendant was still going on below, with yells and laughter, and Helen could hear the sound of the man coughing his guts up too – he must have swallowed half the pond going in like he did – but her clattering the door and shouting the odds was beginning to attract a bit of attention and one of the other attendants called along the balcony, ‘Here! You, lassie! Get away fae the men’s side, you wee besom. You too, Missus! Get back to your own side.’

‘Daddy!’ Helen shouted again, alarmed at the silence from beyond the closed cubicle door. Then she grabbed the top edge and pulled herself up, scrabbling with her feet just like she used to do plunking apples over garden walls when she was wee.

There was a scuffle from inside and she found herself with her face pressed against a wall of white towel suddenly stretched over the gap to stop her seeing in.

‘Get down!’ the attendant bellowed. ‘Behave yourself! What the hang do you think you’re doing?’

‘Aw, calm doon,’ said Mrs Hogg. ‘We’re no having an orgy. You’d do better to think about the corpse that’s dee’d in your bath here than wee Nellie getting a keek at a bare bum.’

Helen let go of the door and dropped back down, bending her knees and hanging over them with her hands braced. Of course! Her father was out of the bath. She had seen him drying himself. And so he’d held up a towel to block the view. He didn’t need Helen’s attentions.

She looked up one more time and thought she had to be imagining what she saw. The hand holding the towel, the hand right now lowering back behind the door, wasn’t her father’s or anything like it. She must have mistaken which cubicle she thought she saw him in. This hand was tiny, belonging to a boy, and it was disfigured, the last three fingers lost to some accident or injury, now no more than twisted nubs.

Helen shook away the threatening swoon – for everything suddenly seemed to belong in a nightmare – and gave her attention back to the cubicle next door. The baths’ attendant was inside now and Mrs Hogg had crowded in behind him, the pair of them blocking Helen’s view.

‘This is—’ he said. ‘This can’t— What— I don’t—’ Then Helen heard the slither and thump as he fainted, banging himself against bathtub and woodwork on his way down.

*

It took over half an hour to clear the baths completely. No one was minded to accept that their paid-for soak was to be snatched away from them and, up and down the balcony, the same arguments could be heard.

‘Boiling? Chance’d be a fine thing. Ma watter’s barely warm.’

‘Aye, puir sowel, but it’s nocht to dae wi me, pal.’

‘I’ll bide here till they’ve got him away. Keep out your road.’

It wasn’t until the police came, in the person of Constable Pearson, familiar from his many years on the Fountainbridge beat, that any of the grumbling bathers could be persuaded to dress and leave, assured that they’d be given a chitty for a free bath another night as soon as the problem had been seen to. Mrs Hogg slipped away at some point too, which wasn’t helpful to Helen, since she had no towel with her and no ticket and could not initially explain to Pearson what she was doing there.

The constable had discovered her in a cubicle two doors down. He thought she was washing her hands, probably, but really she was running the hot tap straight into the open plughole, testing the water. It got uncomfortably warm but nowhere close to the cauldron where that poor man still lay.

Pearson barged past, turned the tap off and set about haranguing Helen about how she had come to find the man, blustering on and hardly giving her a chance to answer before he laid into her again.

‘I didn’t,’ she said, when at last he took a breath. ‘I didn’t find him. That baths mannie wrapped in the towel out there found him and he fainted and fell in the pool. Then that other baths mannie with the bleeding head saw him next and he fainted too. It was only me and the woman that gave me the flannel who coped.’

‘And what woman was that?’ Pearson asked. He looked green about the gills too. The mention of the flannel hadn’t helped. It was stuck fast to the dead man’s skin and changing colour in a way that even Helen didn’t care to think about too closely.

‘Mrs Hogg from Orwell Terrace,’ she said. ‘You’ll know her. She’s got five laddies all at the Lochrin wee school and her man’s a cooper.’

‘Big Bella Hogg?’ said Pearson, perking up at the chance to laugh at someone. ‘She’s your bosom pal, is she?’ He had put an emphasis on ‘bosom’ and Helen felt her face flushing, although she’d have said she was so hot and so upset she couldn’t get any redder. She scowled at him and tried not to remember the amount of shifting and hefting it had taken to bathe the top half of Mrs Hogg’s torso. It was none of his dirty business what kind of figure anyone had.

‘She’s my patient,’ Helen said, as grandly as she could. He didn’t query this out loud but

he raised his eyebrows in hopes of an explanation. ‘I work at Dr Strasser’s surgery on Gardener’s Crescent.’

‘Aye?’ said Pearson. ‘Well, we could do with a nurse. Why don’t you go in and . . . at least take the plug out and sort him.’

Helen hadn’t said she was a nurse. Even he hadn’t said she was a nurse. And, although every bit of her wanted to go in there and try to find out who that man was and what exactly had happened to him, Constable Pearson should have known better than to ask.

‘Aren’t you waiting for the police surgeon?’ Helen said. ‘Shouldn’t we be sure not to disturb anything until a detective’s seen him?’

Pearson’s lip rolled back in scorn, turning him as ugly as an ogre from a fairytale. ‘Detective?’ he said. ‘Police surgeon? You’ve been reading too many penny dreadfuls and we’re far too busy to be making work for ourselves on your say-so. Tonight of all nights.’

‘How? What’s happened tonight?’ Helen said.

‘I’ve only just heard this, mind, but there’s a dangerous lunatic on the loose,’ Pearson said. ‘You should get yourself home safe, Miss Downie, and stop meddling in things you don’t understand. He’s made his bath too hot and killt himself, has this mannie. He needs an undertaker, that’s all.’

‘Mrs Crowther,’ Helen said, then paused. If this dolt of a constable really believed that the water came out of the Cally Crescent Baths’ taps hot enough to do what had happened here then she needed two things: she needed him out of the way and she needed someone he would listen to. He clearly wasn’t going to listen to wee Nellie Downie fae Freer Street, even if she was now Helen Crowther of Rosemount. ‘Aye, no bother then,’ she said. ‘I’ll see what I can do for him till they get here from the . . . it’ll be the Co-op, is it? Has somebody run and told them already?’

‘His family should be the ones to do that,’ Pearson said. ‘So you just see if you can work out who he is and then you run and tell them. I’m going to stand at the front door and . . .’

Breathe fresh air and not disgrace himself by being the third man to faint or the first one to boak, Helen finished, into herself.

‘And can I get my boss round too?’ Helen said. ‘Dr Strasser. The family’ll be happier if a doctor’s seen him and not just a . . .’

‘Nurse, aye. Aye, whatever,’ said Pearson. He hadn’t quite said it this time either. ‘I better go,’ he added, quite officiously in Helen’s opinion, as if standing on the steps of the baths building doing nothing was the big job here, and going back inside that cubicle to deal with a boiled man was the easy option.

So, all in all, when she marched downstairs behind him to put her penny in the telephone at the public kiosk and tell them round at Gardener’s Crescent, she was hoping for one Dr Strasser rather than the other. She was hoping for Dr Sarah, rather than Dr Sam. They were both Helen’s bosses, just the same, but Dr Sarah was also her friend and her champion.

It was Dr Sarah who had taught Helen the word ‘officious’, a term she needed to use most days as she dealt with inspectors, ministers, and medical reps who had never met a lady doctor before and couldn’t rise to the challenge.

‘Have you had your tea?’ Helen asked her when she answered the phone.

‘Oh God,’ she said. ‘Is it Mrs Hogg? What have you found? Fungus? Maggots? Gangrene?’

‘For the love of Pete. No, it’s worse than all of that and it’s not Mrs Hogg. Come to the baths, please Doc, and quick too.’ ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...