- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

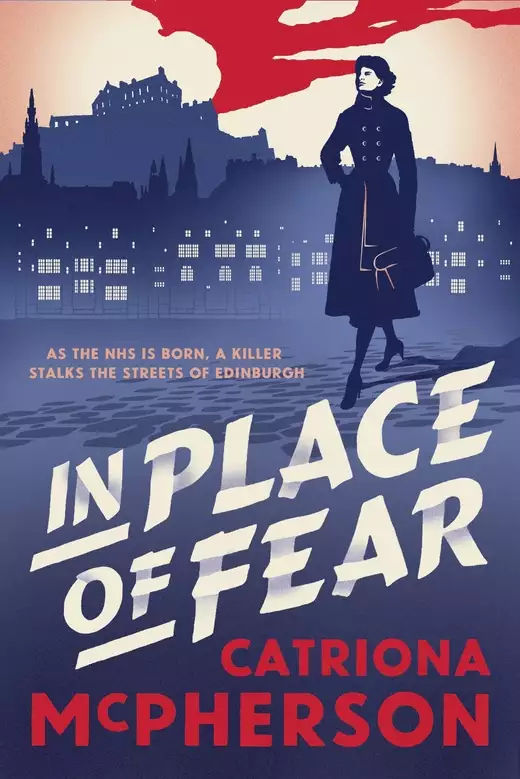

Synopsis

Helen leaned close enough to fog the mirror with her breath and whispered, 'You, my girl, are a qualified medical almoner and at eight o'clock tomorrow morning you will be on the front line of the National Health Service of Scotland.' Her eyes looked huge and scared. 'So take a shake to yourself!''

Edinburgh, 1948. Helen Crowther leaves a crowded tenement home for her very own office in a doctor's surgery. Upstart, ungrateful, out of your depth - the words of disapproval come at her from everywhere but she's determined to take her chance and play her part.

She's barely begun when she stumbles over a murder and learns that, in this most respectable of cities, no one will fight for justice at the risk of scandal. As Helen resolves to find a killer, she's propelled into a darker world than she knew existed, hardscrabble as her own can be. Disapproval is the least of her worries now.

IN PLACE OF FEAR is a gripping new historical crime novel that is both enthralling and entertaining, and perfect for fans of AJ Pearce and Nicola Upson.

Release date: April 14, 2022

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

In Place of Fear

Catriona McPherson

July 4th 1948

Helen couldn’t get a minute’s peace up in the house. Her mother was at the sink in the off-shoot scrubbing carrots for their Sunday dinner, but she could do that and nag at the same time. Her father was propped up smoking in the box-bed in the kitchen. After a hard week’s work and him the head of the house, who would stop him? But he could scold while he was smoking. Teenie was in the bedroom that used to be Helen’s too, before the wedding, but she would come slinking out, hinting and smirking, if she heard her sister’s step. That left the big room. But Sandy was asleep in there. Sandy. Her childhood sweetheart, her brand-new husband, her partner in all of life’s travails, the minister had said the day they took their vows.

And so here she was, locked in the lav in the middle of the back green, looking sternly at herself in the spotted little mirror, delivering a sorely needed talking-to. ‘You are trained,’ she told her reflection. ‘You are ready. Tomorrow is a great day in this nation and you are going to put your shoulder to the wheel and help.’

The door handle rattled.

‘Two minutes,’ Helen called out. She leaned close enough to the mirror to fog the glass with her breath and whispered, ‘You, my girl, are a qualified medical almoner and at eight o’clock tomorrow morning you will be on the front line of the National Health Service of Scotland.’ Her eyes looked huge and scared. ‘So take a shake to yourself!’ she hissed, then unchained the door.

‘You’ve not pulled the plug, Nelly,’ said Mrs Suttie, who was waiting outside with her box of Izal and her Sunday Post. ‘Ach but it saves the watter, eh?’ She shut herself in without waiting for an answer.

Helen’s mother had finished at the sink and the carrots were on to boil. The table was laid with the second-best china, the set she kept on the kitchen dresser and only used on Sundays. Now Greet stood with her back to the range, ironing the very last of the week’s wash, finally dry after all the warm, damp days. She was pressing the smell of the dinner into them, Helen thought. It was pork today, a good joint of rolled shoulder, but the fat was mutton like always.

Greet munched her dentures, her eyes darting back and forth across the ironing table. If you didn’t know her you’d think she was looking for creases or smuts, waters spots, scorching. But Helen did know her mother. She knew Greet could iron a tablecloth with her eyes closed. She had done it in the black-out, when the night was too hot to bear the thick paper pinned over the windows, and she had done it other times too, Thursdays, saving the gas. What she was searching for wasn’t crumpled cloth; it was the next point of attack.

‘I d’ae trust thon doctor,’ was what she landed on. ‘D’ae trust either of them.’

‘How no’?’ Helen said, since straight-talking sometimes worked.

‘Of course, you’re too young to mind of the old doctor,’ Greet said at last. It hadn’t worked this time.

‘Naw, I’m no’,’ said Helen. ‘I mind of him fine.’

‘You were a bairn. You knew nocht,’ Greet said.

‘So tell me now,’ said Helen. ‘Tell me what the problem is when he’s years deid and away.’

‘His son’s a chip off him,’ said Greet. ‘What are they thinking getting a decent lassie like you to work in beside them, just the three of you?’

‘Will yese wheesht with all that,’ said Mack, from the bed.

But he took it up himself when he sat down at the head of the table for his dinner, an hour later. ‘Never thought I’d see a girl of mine stirring a midden for money.’ He had poured a lake of gravy over his plate as usual, leaving the rest of them short, and he didn’t finish half of it before he had his baccy out.

‘I’ll be giving out leaflets mostly, to start with,’ Helen said. ‘I’m no more stirring a midden than the postie.’

‘Leaflets!’ Mack’s voice leapt with the scorn he always enjoyed so much. ‘Bad as the bloody war again. Leaflets, leaflets.’

Helen had welcomed the flurry of leaflets at the outbreak. She had just left the school and she missed her books. When they came through the door – How to fit a gas mask, food shortage, petrol rations – she’d consoled herself that the same clever people who knew all this in advance and printed it up for every family would never let Sandy be harmed. They’d kit him out with good boots and a helmet, feed him three meals a day and send him home to her. She had saved the leaflets whenever she got to them before someone else used them to light the fire. She read them and re-read them, in place of letters, until they were as soft as chamois leather and fell back into folds when she let them go.

‘You d’ae have to go through with it,’ Greet said, with a mouthful of carrot. ‘Just swallow your pride. You ken I’ve got you all set for a job in wi’ me.’

It sounded like kindness but Helen knew better.

‘I do ken,’ Helen said. ‘And I’m grateful. If this doesn’t wor—’ She managed to stop herself from saying her mother’s job was a second-best to fall back on. She managed that much.

‘It’s a lot of strain on you,’ Greet tried next. ‘Just when you need to be taking good care. You’re married now and soon you’ll have more to think about than leaflets, Nelly.’

Teenie let out an explosive giggle.

‘Mammy, get her telt!’ Helen said as her cheeks flamed. She was more and more sure that Teenie knew. Somehow. Maybe she listened. Maybe Sandy had poured his heart out to her. Helen couldn’t say which would be worse.

‘Och, she just can’t wait to be an auntie,’ Greet said.

‘I can wait, Mammy,’ Teenie said. ‘I’ll have to.’

She definitely knew. Helen couldn’t help shooting a look at Sandy. He was mopping gravy with a heel of bread, Mack watching him like a foreman. He couldn’t charge Sandy with eating too much, given the lake of gravy on his own plate, fag ash floating in it now. And what was a slice of Sunday bread anyway? All of it needing used up before the morning.

‘And you’re sticking, are you?’ Mack said at last, as if the sight of his son-in-law had pushed him beyond endurance.

‘Sticking?’ Sandy said. ‘Sticking by Nelly? Aye, I am that. She’s stuck by me.’

Greet frowned. And right enough it was a strange thing for a bridegroom to say. Shut up, shut up! Helen sent him a frantic, silent message.

‘Two good jobs we’ve got the pair of you,’ Greet said, maybe nudging Sandy to understand the point – for she was always ready to keep an argument alight – or maybe just taking the chance to air her own grievance again. ‘All oor favours called in to get them and the baith of you thumbing your two toffee noses at it. The slaughterhouse has been good enough for your faither and the bottling hall’s good enough for me. Good enough to put meat in your mouth and clothes on your back, Nelly.’ She let her knife and fork clatter down onto her scraped plate – Greet, being one of six, had learned to eat quick or starve and decades into adulthood, when she herself was in charge of dishing out, she hadn’t broken the habit.

‘I won’t thumb my nose, Mammy,’ Teenie chipped in, ‘when it comes to me. I’m looking forward to it. I would have tooken a job for the holidays if you’d had one going.’

But it did her no good, for once. Greet wasn’t listening. She cleared the plates, ready for pudding. It was trifle and usually they’d put aside any amount of bickering so as not to spoil it. Today Greet served it up in cold silence, banging the jelly spoon so hard on Mack’s plate she might have cracked it. The little glass cruet set that was her pride and joy rattled in its wire carrier and, with a glance that way, she tapped a bit more gently to shake off Sandy’s portion.

When the girls had theirs too, instead of eating her own Greet went over to the range and pulled the kettle forward. That was when Helen noticed what was laid on the dresser: a tray set with a lace cloth, cups and saucers, and the milk jug with a doily over to keep the flies off.

‘Whae’s coming?’ she said. ‘On a Sunday.’ Her aunties had been on Thursday night as usual and Greet wasn’t one to let the neighbours run in and out.

‘Never you mind.’ As the words were leaving Greet’s mouth though, there came a rap at the door. It sounded like the head of a cane or an umbrella handle.

Helen’s eyes widened. ‘You wouldnae,’ she said.

But her mother was away along the passage already.

‘Good day to you, Mrs Downie.’ The voice rang out from the bare landing and was hardly muffled when its owner entered their hallway and processed, with heavy tread, to the big room.

Mrs Sinclair! Helen’s mentor, her benefactor, her champion all through the years of the war. ‘Did you close the bed curtains?’ she said, imagining Mrs Sinclair casting her eye over sheets still tumbled at dinnertime. The thought of Mrs Sinclair seeing her bed at all, hers and Sandy’s, made Helen want to shrink her neck into her shoulders and hug herself.

‘I closed them,’ Sandy said. ‘And your ma came in after and had a tidy round.’

Greet was back in the kitchen now. ‘Nell? Make that tea when the kettle boils and bring it through.’

Helen pushed her plate away, her appetite gone as her stomach soured and her gullet softened. She closed her eyes.

‘Feeling sick?’ Teenie said in that way she had. ‘It’s not the dinner, for the rest of us are fine. What’s made you grue, Nelly?’ It would have worked if Greet was in the room but it went over the men’s heads. Helen scowled at her anyway and rose as the kettle started spitting.

If she hadn’t the tea things to deal with, the sight of Mrs Sinclair sitting there still in her church clothes might have stopped Helen dead. She was a large woman, her hair teased out in the style of her youth with a hat perched on top of it all, and she dressed herself to look impressive, not attractive, with wide shoulders and box pleats, a fox fur even on a summer’s day.

Helen picked her way through the good furniture – so much of it that the place felt more like a saleroom than a home: the chenille-covered table with the thick, turned legs and the four chairs that didn’t quite fit under it; another two on either end of the behemoth of a walnut sideboard that was filled with tureens and decanters, never used since they’d been unpacked thirty years before for a present show. Concentrating hard, Helen managed to set down the tray at her mother’s elbow and take a seat, doing it all without the unwelcome surge and tingle of her face darkening. That ready flush was the bane of her life. She had got her colouring from Greet, white skin if she could keep out of the sun, freckles else, and orange curls that neither brush nor pin could tame. Anytime she got through an awkward moment like this one and didn’t turn as red as a poppy she was glad of it.

So there they were, at three of the four chairs round the gate-leg table in the window, looking at each other through the polished leaves of the aspidistra, Greet pouring tea and Mrs Sinclair unbuttoning her gloves.

‘And do you take sugar?’ Greet said, in a grating, dainty whine that made Helen’s cheeks flame after all.

‘Just a little milk if it’s quite fresh,’ Mrs Sinclair said.

Greet’s hand shook as she plied the milk jug and her face was a sudden lash of deepest pink, screaming at her hair. Helen felt a moment of glee, but then seeing her mother bend to check the cup for flecks, and even take a quick sniff, sobered her again. Mrs Sinclair had a cold cupboard out the back of her kitchen with slate shelves and a wet floor. Helen had seen it many times as she helped out at children’s treats, fetching lemonade. All right for some.

‘So,’ Mrs Sinclair said, putting her cup back down after a sip. Greet put hers down too. ‘You’ll know why I’m here, Helen. Your parents asked me to appeal to your better nature one more time before it’s too late.’

Helen said nothing.

‘I don’t think you quite understand,’ Mrs Sinclair went on, ‘because you’re a nicely brought-up girl who has been protected from the nastier side of life, first by your parents’ attention, and then by my careful shielding, even while you helped me out with this and that.’

Helen hadn’t spent seven years at Mrs Sinclair’s side without developing an iron grip on her expressions. She didn’t smile or raise a brow. Nicely brought up? She’d spent her early years on Freer Street and if Mrs Sinclair thought this room, with all its polish and china, was a place to be wary of Sunday milk, she would have sat on her hanky round there. And as for ‘helping her out with this and that’: Helen had been her right-hand girl from morning till night, wheeled out as a prime example of Mrs Sinclair’s good works, for ministers, masons, doctors and even a judge once.

‘But we are in perfect agreement,’ Mrs Sinclair was saying, ‘that you are not equipped, by temperament, by age, or by standing, to do what you are so wilfully and so very inexplicably set on doing. And if’ – Helen had tried to speak, but Mrs Sinclair held up a hand and went on in an even louder voice – ‘And if you are really so unscrupulous as to take advantage of that poor boy having had such a bad war and make hay while he’s still not able to exercise proper control of you –’ She paused (whether for dramatic effect, from the emotion she had whipped up, to hint that three years on Sandy should be over his war by now, or because she hadn’t planned how to end the argument and was lost in it, Helen couldn’t tell) ‘– then I have to say, I have been mistaken in you and I regret lifting you up into prominence out of your proper place.’

‘I’m not taking advantage of Sandy,’ Helen said. ‘I’m doing this to help him. We’d have a job living on his wage alone.’

Greet frowned furiously at her. She had sparse brows for frowning, like Helen’s own, but she made herself clear. She wouldn’t have told the likes of Mrs Sinclair what work Sandy was doing. She’d told Helen’s aunties he had a milk round, since they lived away down Abbeyhill and Leith way and wouldn’t run into him. ‘You’ll have to live on his wage alone soon enough,’ she said. She turned to Mrs Sinclair. ‘I was just trying to explain to her that there’s no point getting used to a big pay packet when she’ll soon be brought to bed and doing what she’s made for.’

‘Mother!’ Helen said. ‘For one thing, it’s modern times now. We can plan. And for another, isn’t it better to save hard while we can, while we’re both working?’

Greet was shocked into a rare silence. But Mrs Sinclair sailed on.

‘That’s another thing I wanted to say.’ She was leaning forward, her stiffly upholstered bust straining. She had on a high-necked blouse and a cameo, but there was still a waft of gardenia as she pressed against the edge of the table. ‘The best thing all round would be a good wage for your husband, Helen. Since even the best-laid “plans”… And I have managed to get a promise of an excellent job for him, with decent prospects too.’

‘Where?’ Helen said. Because it wasn’t as if she wanted Sandy sweeping the streets for the Corporation. She wasn’t ashamed of it, or of him for doing it, but she wasn’t bursting with pride either. And Mrs Sinclair had fingers in so many pies, Dr Deuchar always said, she’d have to start using her toes soon. If she had got Sandy a gardening job down at the Botanics, or even a keeper’s job at the zoo, Helen would. . .what? Would she buckle? Would she give in?

‘Fleming’s,’ Mrs Sinclair said. ‘A clerk in the ironmongery department. And the under-manager is retiring soon. So. . .’

‘But he couldn’t do that,’ said Helen. ‘Fleming’s? Inside all day? He’d be with my father if he could do that.’

‘I thought it was the slaughtering,’ Mrs Sinclair said.

Everyone thought it was the slaughtering – the blood or the smell or the cries of the beasts – even though that made no sense at all. If Sandy had been invalided off a battlefield, maybe. If he’d carried a comrade, blown to bits and with the smell of burnt flesh in his nose and the man’s guts spilling over his hands, then the slaughtering would be the problem and a nice job behind a high counter at Fleming’s with a green apron and a pencil behind his ear would be ideal. But Sandy spent his war in hut thirteen of Stalag 387, captured before the first Christmas and not set free till VE Day. Now, when he wasn’t sleeping or eating he was outside. He walked miles when it was dry and sat under the lee of the wash house wall when it rained. Helen could hear him right now, letting himself out the front door. She knew she wouldn’t see him again till teatime.

‘No,’ she said. ‘It’s the four walls. Not the blood. He needs to be out in the air.’

‘Pushing a dustcart.’ Mrs Sinclair was putting her gloves back on. ‘Is that what you dreamed of, Helen? When you were a girl? That you’d be so stubborn, so thrawn, you would consign a fine up-and-coming young man like Alexander to pushing a dustcart?’

Consign him? Helen thought. I didn’t capture him. I didn’t keep him prisoner. I didn’t plan that stupid offensive that handed him to the Germans.

‘No,’ she answered at last. ‘I never dreamed of anything like it. But a man’s got to work at something unless he’s a gentleman of leisure. Here, Mrs Sinclair, what’s the wage at Fleming’s? I could take the job and maybe Sandy could walk in the Pentlands all day instead of behind his cart.’ Helen spoke out of something more than devilment, out of a threatening upswell of what felt like hysteria. The combination of what was coming in the morning – her fear and excitement and the surprise of it all – added to the sight of Mrs Sinclair sitting there, feet from Helen’s bed, in her high hat and her fox fur, not to mention Greet quivering with indignation but forced to contain it by this battleship of a woman in her own house… it all made Helen feel as though something might burst out of her any minute, all the more unsettling because she didn’t know whether it would be laughter or sobbing when it came.

Unbelievably, none of her turmoil showed on the outside and when the mist cleared Mrs Sinclair was answering her suggestion, quite calmly if with a bit of irritation. ‘It’s a job for a man,’ she said. ‘And this nonsense you’re threatening is a job for a lady.’ She said the word as if it was the name of an exotic creature that Helen wouldn’t have come across before. ‘Your own dear mother has a perfectly nice job for a girl, she tells me.’

A ‘nice’ job indeed, Helen thought. Standing in the clattering racket of the bottling hall all day, in the stink of the malt, learning to lip-read gossip, coming home with glass cuts all over your hands and your pinny reeking. The very thought of it settled her down again.

‘Thank you,’ she said, out of this new calm. ‘I do appreciate your concern.’ She was using the words Mrs Sinclair had taught her and the voice too, not her own voice and not Greet’s strangled attempt at gentility. But this wasn’t devilment. It was practicality. She was going to have to start speaking up and being clear tomorrow. This was a wee practice and it felt good. ‘The thing is,’ she went on, ‘I am suited by temperament.’ She felt her chest lift as she spoke, her shoulders pulling back. Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Greet put her head on one side, just slightly, like a bird, and regard her with a new kind of curiosity. ‘And I’m suited by training, as you can hardly deny.’ Mrs Sinclair’s eyes widened so far they seemed to bulge and at the same time her mouth pursed so tight it disappeared. Her rouge, worn high on her cheeks in two circles like the paint on a baby doll, faded into invisibility as a livid flame rose up from her collar and engulfed her face. But Helen still wasn’t done. ‘I was offered the job because they thought I’d shine in it,’ she said. ‘And I am determined not to let them down and make them regret their faith in me. They’re all going to be stretched thin this next wee while –’

‘How would you know that?’ said Mrs Sinclair.

‘It said on the leaflet,’ Helen replied, so smartly she was almost interrupting. She had learned it by heart, thrilling at the words. ‘“If the beneficiaries are to catch up with all their rights, he – that’s the doctor – will have to be a guide, a philosopher and a friend”.’

‘I don’t need a lecture!’ Mrs Sinclair as good as spat the words.

‘And I’m going to help them every way I can,’ Helen said. ‘Which I couldn’t have done without you and your kindness. So, thank you.’

Mrs Sinclair said not another word. She stood, blundered her way clear of the tea table, letting her chair scrape roughly on the lino, and swept out, stumping along like an angry giant after the blood of an Englishman.

Greet, Helen noticed, was crying. Her heart swelled. At last! She had made her mother see. She had maybe even made her mother proud.

‘Mammy—’ she began.

Greet cut her off. ‘For shame. For black shame. I tell you this, Helen Crowther, you can get your airs and graces and your pert, thankless ways and take that useless lump of a husband and get out of this house.’

‘What do you mean “useless lump”?’ Helen said. Did Greet know too? Was she just better at hiding it than Teenie? Was all this talk of woman’s purpose supposed to make Helen break down and tell?

‘If you go to that Dr Strasser and his pal the morn’s morn then don’t come back here at night,’ said Greet. ‘And when you fall, and your precious job is a fading memory, don’t think I’ll be at your beck and call for baby-sitting either! Plan! Plan, you say, bold as brass! I’ve a good mind to tell your father how you just showed me up.’

No, Helen thought, she didn’t suspect at all, did she? ‘Be my guest,’ she said, knowing her mother would do no such thing, for Mack had to be protected from the like. She stood and marched to the door, then faltered remembering that her and Teenie’s room wasn’t her and Teenie’s room any more. Instead she swerved, wrenched open the curtain over the box bed and climbed in, pulling it shut behind her. She would stay here until Sandy came back and then she’d have it out with him, once and for all. That’s what she would do. She’d tell him she needed her mind on her job, not fretting over him, waiting and wondering. She’d tell him he owed her a bit of straight-talk, plain dealing. An end to it or an explanation.

She rolled onto her back and stared up at the tongue and groove panels of the ceiling, so thick with paint they barely had dents. She wouldn’t say anything. She was as bad as her mother. She would just put it out of her mind and be grateful to know she was free to do her job and not worry that she’d soon be boiling nappies instead. Her job. Her wonderful miracle of a job in this wonderful miracle of a thing that would start in the morning, all over the city, all over the country. And her – wee Nelly Downie fae Freer Street – a part of it! That would do.

Chapter 2

Clothes maketh the man, was one of Dr Deuchar’s little sayings. He had a hundred of them. Helen was kneeling on her heels with both drawers open, looking over her choices for the day. If it was winter she’d wear grey serge with cream cuffs buttoned on, but she’d stew in that today and have dark rings under her oxters by dinnertime. So a skirt and a blouse. She’d take a jacket with her and put it on a hanger on the back of the door like the doctors with their overcoats. Never a peg through a loop, always a hanger. She used to think it was funny that they brought a coat down to the surgery when they lived upstairs, but after she’d seen them go flying out on an emergency call a few times, grabbing bag and coat without breaking stride, she admired them for the forethought. She wouldn’t have emergency call-outs, of course. Would she? The little worm wriggling in the pit of her belly started thrashing at the thought of it. It was the same little worm that had told her not to try even a bite of breakfast.

Get started, she told herself. Dress yourself for the first day. By Christmastime, if someone called her out on this imagined mercy dash, she’d be ready. Get started today. Dress the part. Clothes maketh the man. She had a good pair of stockings with not a single thread pulled on them, as well as a black straw hat she’d never worn on a Monday before now.

‘Don’t sit like that.’ Greet was behind her suddenly. ‘You’ll get veins.’

Helen shoved the drawers closed and twitched the edge of her eiderdown over the top of them.

‘Never mind straightening – I’m going to strip that bed and get the sheets in,’ her mother said. She had lived on the stair enough years to have got Mondays in the wash house and drying green and she liked to start her whites soaking before work, not trusting old Mrs Suttie to do them justice. She’d be back at dinnertime, looking over Mrs Suttie’s shoulder as the blouses and shirts went in, rushing home to do jerseys and stockings herself before tea. Never mind that Mrs Suttie always said she could manage. ‘Them as pays the piper,’ was Greet’s reply. ‘I wouldn’t put it past her to bunch mine up and make room.’ She ‘paid’ Mrs Suttie in meat that Mack brought home – liver and bones and the odd fatty knuckle – but you’d never know it from the airs she put on. Even when they were in summer clothes all day and a single sheet to cover them in the hot nights, Greet would scrape up a day’s worth of washing and a green’s worth of drying from somewhere rather than leave a breath of warm in the copper or an inch of rope for someone else. ‘It’s my day,’ she always said. ‘They’ve got their own days and you don’t see me coming begging.’ Once, in the war, Helen had pointed out that there were only four of them and no men coming in from the works in boiler suits, seeing as how Mack’s aprons got done at the slaughterhouse laundry. Greet had washed every blanket in the press and every mat off the floors, with her jaw set as if it was bound up in a bandage.

‘Thanks, Mammy,’ Helen said now, bowing her head to hide the smile. Greet must be torn in two, caught between keeping up the pretence of putting her daughter out and the need to fill that copper with linens on this sunny Monday.

‘Make it up fresh for whoever’s in there next,’ Greet said.

You had to hand it to her. Helen even briefly wondered about saying thanks again, because surely the cussedness making Greet keep on with a story of banishment was the same cussedness, handed down, making Helen believe she could do what she was doing. Greet’s trouble, one that Helen didn’t share, was how to get out of the hole she had dug.

‘Aye, fine,’ she said, going along. It wasn’t her job to make things easy. ‘I’ll strip them and bring them down.’

‘I can do it.’

Helen stared up at her mother. ‘What?’ Greet said. ‘Think it’s anything I haven’t seen before?’ She was in about the bedclothes already, bundling the eiderdown and plucking the pillows from their cases. ‘I’ve not got time to be waiting till you’re dolled up for whoever it is you’re dolling up for. I need to get this lot soaking before the horn.’

Whoever it is I’m dolling up for, Helen thought, as she stepped into the new stockings and fastened them. That was the meat of it. That was the real trouble, no matter it was a lie. No one – not even her own mother – believed she wanted the job for the sake of the job. But it was true. The only man she’d ever dolled up for in her life was Sandy Crowther. She looked at the dark patch of hair oil on the bare pillow, then turned away before her eyes could fill and streak her face powder.

For a wonder, she didn’t pass a neighbour on the stair and it was the perfect time of day to get along the street: too late for menfolk whose day shifts started at seven and too early for any women headed towards the bottling hall and brewery for eight.

Hurrying along Founta. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...