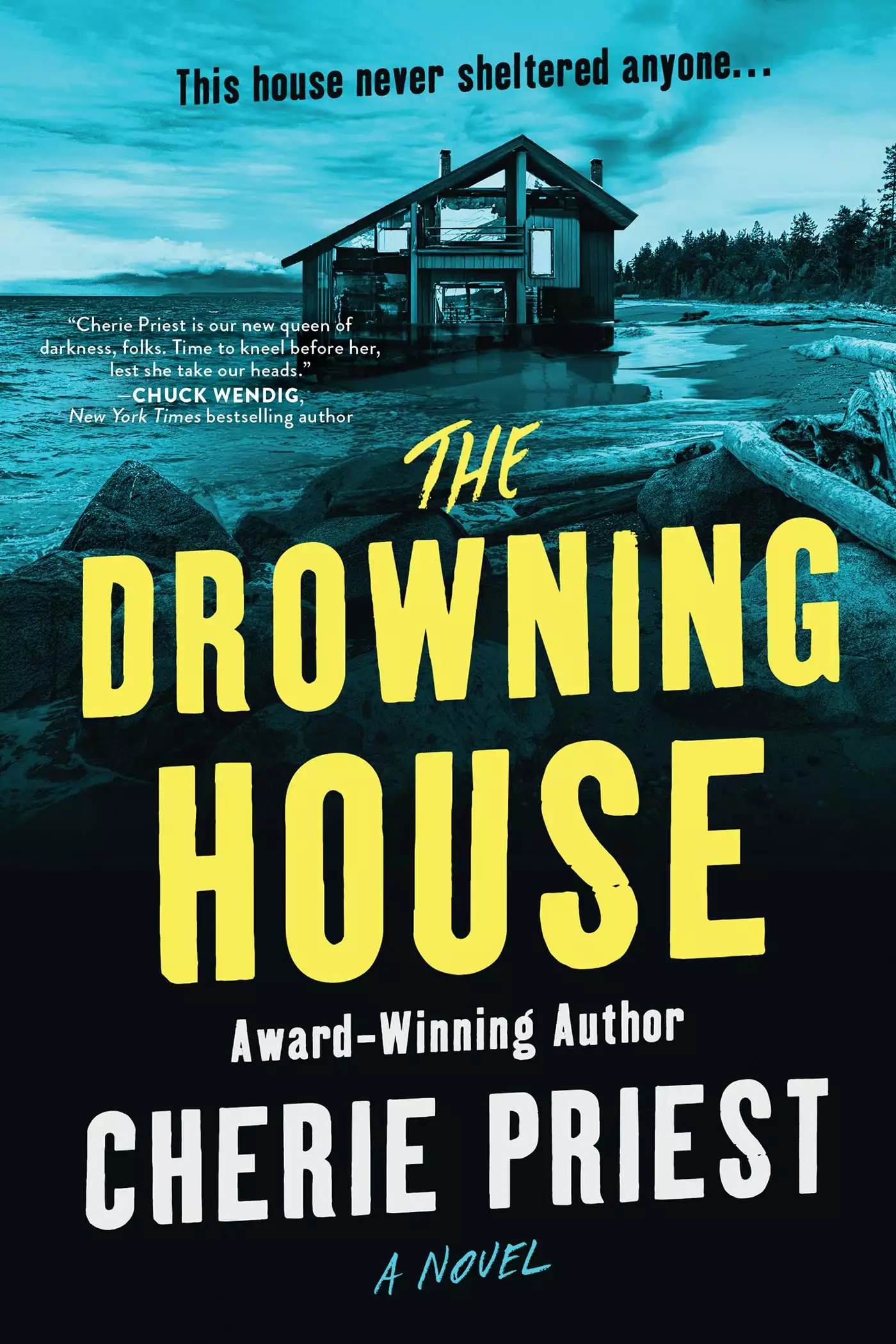

The Drowning House

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

"This smartly paced, genre bending novel is a good choice for the horror-curious thriller reader who enjoyed The Good House by Tananarive Due and Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia." —Booklist, Starred Review

"Cherie Priest is our new queen of darkness, folks. Time to kneel before her, lest she take our heads." —Chuck Wendig, author of The Book of Accidents

Houses fall into the Pacific Ocean all the time.

Not one has ever come back. Until today.

A violent storm washes a mysterious house onto a rural Pacific Northwest beach, stopping the heart of the only woman who knows what it means. Her grandson, Simon Culpepper, vanishes in the aftermath, leaving two of his childhood friends to comb the small, isolated island for answers—but decades have passed since Melissa and Leo were close, if they were ever close at all.

Now they'll have to put aside old rivalries and grudges if they want to find or save the man who brought them together in the first place—and on the way they'll learn a great deal about the sinister house on the beach, the man who built it, and the evil he's bringing back to Marrowstone Island.

From award-winning author Cherie Priest comes a deeply haunting and atmospheric horror-thriller that explores the lengths we'll go to protect those we love.

Release date: July 23, 2024

Publisher: Poisoned Pen Press

Print pages: 425

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Drowning House

Cherie Priest

A fat harvest moon hung low over the beach the night Tidebury House washed ashore—over the wet, packed sand and ragged black rocks, all the way past the edge of the high-water line. It dripped with dirty foam and seaweed, and it rested crookedly, draped with rotting nets, crusted with barnacles. Tiny clicking creatures with small sharp claws climbed the teetering two-story structure and then—finding nothing at the top but a collapsed roof and the ghosts of broken chimneys—retreated again to the shelter of briny pools, where they waited for the waves to return.

Tidebury House never sheltered anyone. That’s not what it was for.

The brutal, late-autumn storm had not quite receded when Charlotte Culpepper grabbed her house robe and slippers. “It’s not possible,” she muttered as she crammed her naked feet into the soft satin shoes. She threaded her arms into the robe’s sleeves and cinched its belt around her waist. “Not possible, no.”

She stumbled at the edge of the hallway runner and caught herself against the wall. Must be careful. Mustn’t fall. Not again. She’d never recover from another one, not at her age. Where was her cane? She’d left it behind, beside her bed, leaning against the nightstand. No matter. She wasn’t going far.

Her heart thundered in her narrow chest. She clutched it, and she fought for balance. One hand against the wall, her fingertips sliding down the textured grasscloth wallpaper. One foot in front of the other.

“It won’t be there,” she lied out loud. “I hid it from the world. I sent it away.”

A sleepy, confused voice called out from the bedroom down the hall. “Grandmother?”

She shouted back, “You heard it too, didn’t you? It was loud enough to wake the dead!”

Simon opened his bedroom door and yawned. “Did a tree fall on the house?” Then he noticed that the elderly woman was hustling toward the front door in her night clothes. The realization woke him much faster and more thoroughly than the crash outside. “What are you doing? Are you all right?”

Beside the front door, a wicker basket offered three umbrellas. She ignored them. The coat rack held two of her raincoats—one for lighter weather, one for wetter and colder. She left them both behind and reached for the dead bolt. She twisted it hard and then released the chain above it. She did not so much open the door as yank it inward.

Rain blew sideways into the foyer. The sharp, wet wind clutched at the dangling light fixtures and flapped through the raincoats. It rattled the umbrellas, the pillows on the parson’s bench, and the philodendron with the long green tentacles and heart-shaped foliage. The sprawling old houseplant swayed and fluttered; its loose leaves fell free. They bounced and lurched in the spiral gust that

circled the elderly woman like a spell.

“Shut the door, please!” Simon begged. “Stop it, Grandmother. I’ll go check. I’ll find out if there’s any damage. I’ll go see how bad it is, you stay here.”

“The damage,” she muttered.

She already knew it was no tree. Not even the hundred-foot alder behind the house would’ve made such a racket. She’d heard that sound before: the violent crunch, and the teeth-splitting scrape over the peculiar thunder that shook the night in a rumbling, protracted roar. It could be nothing else.

Except it wasn’t possible. It was too cold for thunder. Far too late in the season for this sort of storm.

Wasn’t it?

Leaning hard against the weather, she launched herself onto the porch. Her feet hit the cedar boards; she slipped, she steadied herself.

The air sizzled with ozone and fire. A flash too close, too hot and sudden.

The power went out.

All the ambient light in the big old house disappeared in an instant. No glowing clock numbers from the stove in the kitchen, no soft night-lights in the hall to guide the way to the bathroom. No lamplight spilling out of her grandson’s room.

No moon. Nothing, except…

She wiped wet hair out of her eyes and saw the flash of lightning in the distance, silent and bright. Sparks flying from the power lines. The lighthouse at the north end of the island, its lamp burning a streak of white that swung back and forth across the churning water in the shipping lanes—powered by its own emergency generator.

Everything else was black.

Charlotte scrambled down the three short steps to the ground, clutching the rail all the way. Her feet hit the brick walkway and slipped, but she still had one hand on that rail. Against the odds, she stayed upright. Leaned against the wind. Squinted against the driving rain that still spit hard off the water.

It was hard to see. Impossible, if you didn’t know what you were looking for.

Charlotte knew, and when the sparkling edges of the night’s wee hours showed something

enormous resting at the beach’s edge, she almost stopped breathing.

Instead, she started running.

Her joints ached and her chest burned. She was closer to a hundred years old than most people ever come, but she had never been as fragile as her grandson believed. Once, she’d stood against a bigger storm than this, and she’d wielded the earth itself against the ocean, against a house, against a man.

But the cost had been great, and she could not pay it twice.

She stopped running. Her lungs screamed and her ankles popped; her ribs ached and her eyes stung. Simon was calling out, but she couldn’t hear what he was saying. When she checked over her shoulder, he was only a flailing shadow. He stumbled forward, feeling his way from the house in the trees to the edge of the water. When the lighthouse lamp swung her way for the briefest instant, she saw him struggle toward her in sock-feet.

Before her: the terrible square block of darkness, somehow blacker than the night that surrounded it. She could see nothing past it. Not the thrashing waves, not the swelling tide, not the horizon line, or the land on the far side of the Sound.

Slowed by age but propelled by terror, Charlotte pushed forward.

She knew every boulder, every driftwood log, and every grass-covered dune at the edge of her property. She knew where to step and where to avoid, but there might be new debris. There could always be fresh obstacles between Charlotte and the beach.

None of it was half so dangerous as the thing that couldn’t have possibly come back onshore.

All the same, there it was: a structure carved out of a black hole, with all the same inscrutable gravity.

Charlotte hadn’t seen it in seventy years. Apart from a faint outline when the lightning flashed, she couldn’t see it now. It absorbed the reality around it. It consumed everything. Everyone.

Simon came running up behind her at an uneven pace that half slapped, half stomped.

“Stay there!”

She held out her hands. “Don’t come any closer!”

Years before, she’d stopped worse things that way. A lift of the hands. The raising of a horn. Old words in the old family tongue, carefully pronounced. Old words, shouted. Given to the earth. Thrown at the water. Now forgotten. Old.

Words. Lost.

Charlotte gasped. Her vision went white and spangled. She dropped to her knees. Something inside cracked. She heard it, but she did not feel it. She opened her mouth in case the old words would come falling out. In case they still lived inside her head and might be summoned.

Nothing came out. Not even air.

Hands reached her. Touched her back, on her side. Lowered her to the ground, where it was rough and wet and the sand squished beneath her shoulder blades.

“Simon,” she tried to say. “Run,” she would have added. “You have to run, before he. Before. Before.” Her lips shaped the words, or maybe they only moved because her teeth were chattering.

“Grandmother,” he wheezed. “Don’t move, hold still. I’m calling 911.”

He was a stranger now, some unknown party with unclear motives, and she would have fought him if her arms worked at all. If her legs could kick. If she didn’t taste pennies and salt. If she could see anything through the stars that filled her eyes—except for the uncanny shape that loomed large over the beach and the movement within it,

and the light within it, and the shadow within it

the man within it, sliding back and forth between then and now

here and there

now

All three children sat on the sand atop a series of towels they’d borrowed from Mrs. Culpepper. The towels were entirely too fancy for an oceanside lounge, with fringes and velvet trim; they were cotton/silk blends that were mostly for show in a rarely used bathroom. But Simon had begged. As he’d vigorously reminded his grandmother, the weather was uncharacteristically warm and there wouldn’t be many days like it. The kids could either take advantage of this happy boon…or play inside the house—where they would surely drive the old lady batty.

On purpose, if necessary.

“Don’t go any deeper than your ankles,” Mrs. Culpepper had warned. “Wading is fine, splashing is acceptable, and damp knees are to be expected. But no swimming. I know it’s hot outside but the water is too cold for swimming, and the current is stronger than it looks.” Then she’d given them the towels and kicked them out to do their worst.

Now these pasty Pacific Northwesterners had sun, they had time to kill, and they had a beach.

Or if not a beach, they had a coastline—and it stretched along the eastern side of a slender, minimally occupied island on the western end of Puget Sound. Sure, this coastline was covered in gravel and crushed shells, and yes, it was pocked with volcanic black boulders that were too sharp to climb without bloodied elbows, knees, and palms. But it was long and narrow and private, just out of sight from the Culpepper house on the other side of the tree line.

The ocean hovered around forty degrees most of the year. In August, maybe as high as fifty.

It was only the end of June.

All three children sprawled in a row, wearing their smallest clothes. None of them owned bathing suits, but they all had shorts and Melissa had a tank top rolled up to cover little more than her nonexistent boobs.

Simon was eleven years old. He had hair and freckles the color of carrots, and the lanky, pale body of a boy who wouldn’t hear from puberty for another couple years at soonest. His eyes were the color of the sky past the horizon line, mostly blue with a bit of gray. He’d lived with his grandmother since his parents had died in an accident when he was eight.

Melissa was also eleven. She’d been a towheaded baby and now was an ashy blond child. Mrs. Culpepper had offered her tousled head a spritz of lemon juice to let the sun brighten those dull, unruly locks. “It’ll give you highlights,” she’d promised. Given time and no further lemon juice intervention, her hair might eventually catch up to her eyes, rich and golden brown.

And then there was newcomer Leo, seven years old. Small and round. Darker in complexion than the other two, with black wavy hair and eyes that matched it perfectly, until you saw them in the light.

He was chatty and excitable and eager to please—desperate to fit in with Melissa and Simon, who were the only other children on the island. Despite his efforts, he remained a third wheel wherever they went—even if they were only going down the walkway, past the big driftwood tree that was as long as a truck, and through that narrow gap in the seagrass-covered dunes, onto the rocky sand beside the ocean.

Regardless, Leo was happy, especially when the sun was out. Even if the big kids didn’t include him in every conversation, even if they talked over his head. He had a baby blue towel with a faux-Persian velvet pattern around the hem. It was very soft between his fingers when he fiddled with it.

He wished for sunglasses, but he didn’t have any. Neither did Simon, but Melissa was wearing a pair of Mrs. Culpepper’s that were comically oversized on the little girl’s face.

Simon pointed out, “You’ll get funny tan lines, if you don’t take those off.”

She shrugged. “I don’t care. I like them. They make me feel rich.” Melissa was not rich. Her parents sent her to stay with her grandparents every summer because they couldn’t afford daycare when school was out.

Leo said, “I like the sunglasses. They make you look grown- up and important.” Leo’s family wasn’t rich either. He was living with his aunt and uncle part-time for the same reason as Melissa. Their house was through the woods on the next lot over.

“Thank you, Leo. See? He’s little, but he’s not stupid.”

“He’s not that little,” Simon said, with a friendly elbow to the younger boy’s shoulder. “One of these days, you’ll be bigger than both of us, I bet.”

He liked that idea. “Then I shall have vengeance!” he declared, as close to the tone of his favorite Saturday morning cartoon character as he could manage.

Simon and Melissa cackled. They knew the show too.

Their laughter pleased the smaller boy. But he still added, “I’m just kidding.” He sat up and then reclined on his elbows, staring off into the ocean

He liked the unusually hot day. It didn’t often crest eighty degrees that far north and west, and nearly ninety was a rare thing indeed. The ocean breeze made it feel wonderful and pleasant; it smelled like salt and cool, wet things—but it felt like summer and soft, warm things.

“Look at me,” said Melissa, not for the first time. “My skin is already getting kind of…” She poked her shoulder, and then gave it a pinch. “Pink. I’m getting a tan.”

“So am I!” Simon announced. He pressed his hand to the top of his thigh and removed it, leaving a white impression in the sunny blush.

Leo jabbed at his own thigh, his own shoulders. “I’m not.”

“You’re not as pale as us,” the girl informed him. “It’ll take more sun to make you darker.”

Simon patted his arm. “I bet Melissa and me will get a burn. But you’re lucky. You probably won’t.”

Melissa said to Simon, “Maybe you’ll get a burn, but not me. I’m going to look like Brooke Shields.”

“Does she have a tan?” Leo asked. He wasn’t sure who she was.

“She did in The Blue Lagoon. I saw it on video. We rented it from the gas station down the street from my parents’ place.”

Simon asked, “Was it good?”

She shrugged. “Sometimes Brooke Shields is naked, and her skin is really gold. Mine will be gold soon.”

Leo didn’t argue, but he knew what sunburn looked like, and his friends were definitely getting some. His uncle owned a company that did construction work around the Sound and he’d seen his uncle’s shoulders, bright cherry red on top of his usual bronze. He knew what a farmer’s tan was, and how brown skin can singe and peel, just the same as pasty skin with freckles.

Melissa sighed at the waves. “I want to go for a swim.”

Simon said, “No, you don’t; it’s freezing.”

“I don’t care about the cold.”

“You will when you’re wet,” he insisted.

Leo was just as tough as Melissa, he was pretty sure. “I don’t care about the cold either.”

Melissa was less confident. “Then why don’t you dive in?”

“Mrs. Culpepper said we shouldn’t. It’s not just cold; the water is strong. It’ll take us out to sea if we go too deep.”

She rolled her eyes. “Mrs. Culpepper says a lot of things. It’s only water. It’s not that cold, and it’s really hot out here. You’d be fine.”

“No, Grandmother’s right about the water. There’s an undertow. It’ll grab you

by the feet and sweep you away. You’ll go out to sea and drown, if you don’t freeze to death first.”

As if she had any idea what she was talking about, Melissa dug in. “You can’t freeze to death if it’s not even cold enough to make ice,” she said with confidence. “Don’t be a chicken,” she told Simon. Then to Leo, “Don’t be a baby.”

Now the little boy could feel the pink. It crawled up his neck and settled into his cheeks. “I’m not a baby.”

“You act like one.” She adjusted the sunglasses and settled back into her towel. “If it looks like a baby and acts like a baby, it must be a baby.”

“I’m not a baby,” he protested through gritted teeth.

“Prove it.”

Simon didn’t like it. “Melissa, don’t. Come on. He’ll get hurt, and we’ll get in trouble.”

“He won’t go out there. He always does what he’s told, because he’s a baby.”

“He’s just…not as old as us. We weren’t babies a few years ago either. Don’t listen to her, Leo. Stay here on your towel. Simon says: Stay.”

“I don’t always do what I’m told,” he grumbled. But he felt very hot now, and he was sure he was finally getting a sunburn. Cold water would feel good on a burn, wouldn’t it? That’s what the school nurse said, the one time he came to kindergarten after he touched the stove.

“If you get hurt, Grandmother will kill us,” Simon said, meaning him and Melissa. “We’re supposed to look out for you.”

“Because I’m the baby.” He sulked a little harder. Then he stood up. A corner of the towel stuck to his foot, and he kicked it off. “But I can get in the water. Mrs. Culpepper said we could go wading.”

“That’s…true,” Simon said warily.

“Then I’ll wade.” Up to his knees, at least, would be safe. “I’m not afraid of the water.”

“Maybe you should be,” Simon said, watching the younger kid stroll with feigned confidence toward the edge of the tide. “No deeper than your knees!” he called.

Leo waved without

looking back.

He was barefoot and wearing only a pair of jersey shorts that weren’t really swim trunks, but how often did he need swim trunks, anyway? The sun blazed down dry and hot and so bright that he wished he had a pair of Mrs. Culpepper’s sunglasses to wear too. Even if they looked silly. Even if they wouldn’t stay on his face.

His toes and heels sank into the sand as he trudged past half dried tide pools, oddly shaped shells, limp seaweed, and the scuttling crabs that he’d already learned not to pick up for closer examination. He wasn’t afraid of them, but he knew not to touch them. They pinched.

“Seriously, Leo—don’t go deep!” Simon commanded from his towel.

Simon said something to Melissa, and she said something sarcastic in reply, but Leo was far enough away that he didn’t hear what it was; he just recognized the tone.

His toes hit the water. It foamed up around his feet and retreated, then returned—the little waves at the edge of the sand creeping onshore. The tide was coming in, but it wouldn’t reach the towels for hours. It was rolling up cold, as frigid as anything he might take from a jug in the fridge, or a can of soda freshly cracked and fizzing. His body lit up with goose bumps, despite the toasty warm sun on his back and shoulders.

It was a strange and thrilling contrast, being too hot and too cold at the same time. He wiggled his toes in the chilly, wet sand and let them sink.

The waves were not so scary. They crawled up short and shallow around his ankles. Their current did not pull him anywhere. Their coldness did not turn his toes blue or make him want to run and put on socks.

He went out a little farther. Now the waves came up to his shins, and his goose bumps got goose bumps.

The sun was brilliant and the sky was perfectly clear; the air was so warm that it almost made him forget the cold. It made him think that the cold was not so bad, and he could—perhaps, if he was careful and slow—take some more of it, and that would be fine. The water was not strong. The water was not frozen. The beach was right here, under his feet. The sands might shift and the water

might sweep in and out, but it wasn’t going anywhere.

And neither was Leo.

He took another few steps, another few yards.

A wave crested at his knees and he jumped, startled. It was the skin behind those knees, so sensitive to the cold. He hadn’t expected it—the frigid wash that foamed and bubbled around his legs.

He hugged himself and went deeper.

“Leo!” Simon called from shore. “That’s far enough. Come back, please?”

He pretended not to hear.

Melissa chimed in. “Come on, I was just messing with you. Don’t do anything stupid.” When he didn’t answer, she added, “Please?”

Leo smiled. And he kept walking.

Until suddenly, he wasn’t. He was falling, backward into the surf.

It happened suddenly, almost instantly. The water had gone over his knees, up his thigh, and then something had grabbed him. Not with hands, not with claws or tentacles. (He’d learned about octopuses just a few weeks before, from a show on TV.) It’d been a force, something aggressive and hard and so fast that he almost hadn’t felt it; he’d been upright, looking through the clear, cold water at the sand and tiny fishes…and then he’d been on his back, staring at the sky, being pulled along by his ankles and shoulders, his back and his elbows, everything dragged away, toward Whidbey Island on the horizon.

At first, he was too surprised to breathe. He only floated away, astonished by his circumstances.

It felt like lying on a conveyor belt, the kind that brings the bags into the airport—he’d seen one, last summer, when he and his parents had flown out to meet his grandparents in California. He’d been fascinated by the unending flow of bags, resting motionless and moving swiftly at the same time, down the metal conveyor, around and around until they were collected by their travelers.

Now he felt like one of those suitcases, along for the ride to heaven knew where.

Leo knew how to swim, but that’s all you could say about his skills. He wasn’t a strong swimmer, or a fast swimmer, and he wasn’t coordinated enough to swim in a straight line. But he should be able to hold his head up and breathe. Why couldn’t he hold his head up and

breathe?

It must have been the cold.

He’d never been so cold, so completely, in his whole life. He was so cold that he could feel nothing else, not even fear. Not even confusion. He knew what was happening: he was cold. That was enough. That was everything.

At the edge of his awareness, Simon and Melissa were screaming his name, screaming for Mrs. Culpepper, and just plain screaming. But what good would screaming do? What action could Mrs. Culpepper take? She was very old, hideously old—sixty years old, at least. Decrepit and helpless against the ocean. What could she do if, if,

how could she even

but what if

His thoughts curdled.

He smiled, thinking of ice cream firming up in the crank tub, getting thicker and slower as it chilled. He heard a noise. Something far away. No, not very far? It was hard to tell with the water in his ears and the cold in his bones. He did not recognize the sound. It was very low, very loud, and rather musical. He could hear it under the water, when his ears dipped below the surface. The vibrating rumble, the roar of something being called, followed by the crash of something answering.

He couldn’t hear Simon and Melissa anymore. He must be very far out to sea by now. Probably halfway to Seattle, which was over there somewhere, on the other side of the water. He’d been there once—to the Pacific Science Center, where the nice ladies in matching blue vests had let him touch the tornado’s fog as it spiraled from the machine in the weather exhibit.

The fog had been cold too. It had been a vapor, more seen than felt. It was nowhere as dense and not nearly as cold as the all-consuming darkness when he closed his eyes.

Under the waves, something moved.

He didn’t feel it so much as sense it—not the pull of current on his limbs, not the rush of water…but the awareness that far away something very large was alive, and awake, and moving.

Toward him.

He could feel the noise through the water, the echoes and vibrations of something pitched lower than bass. He almost enjoyed it. He could almost appreciate it. Something large was coming, coming for him,

coming to help.

Something would. Someone would. If not Melissa or Simon, who were not strong swimmers themselves then maybe

no not the old lady either, could she even swim

probably not

proba

pb

He sighed, and the last of the air in his lungs floated up in bubbles. So that was which way was up. If he followed the bubbles, he could see the sky above. Cold and blue. Cold and white. The sun was only a sparkle.

But something rushed toward him.

It washed him away; it pushed him deeper into the tide. Only for a moment. Then the jerking and pushing stopped. Something enormous rose up beneath him, and in front of him. Something hard that scratched up his back when it hit him and knocked against the back of his head.

He tumbled in the tide, upside down and right side up and rolling, now that the world was full of rushing bubbles and blinding sky.

Up through the water he came, borne on the back of something he couldn’t see, but when he looked toward shore, to the right, to the west, he could see her coming. Mrs. Culpepper was walking across the water, coming right for him.

Not rushing or running, for she seemed to lack the footing.

But coming.

Splashing and struggling all the way out into the surf, past the spot where the waves broke into foam and puddles. Walking on water, just like Jesus, or that’s how he’d heard it in church.

Mrs. Culpepper was there, balancing on something just below the water, standing wet and ragged and fierce. He’d never seen her look so fierce before, so angry and so frightened and something else, something he wouldn’t put his finger on for another forty years, almost.

She shoved her hands through the surface and seized Leo Torres, age seven. Beloved nephew of Marco and Anna Alvarez. Temporary resident of the house on the next lot over.

She got him by his shoulders, and then she heaved him up out of the water by

his armpits—and hung him over her forearm like a dishcloth while she pounded the heel of her palm against his back.

After the fifth or sixth smack, water burped up out of his lungs and he began to cry.

His lungs emptied, he coughed and sobbed and dangled over Mrs. Culpepper’s arm as she carried him back to the shore. He stared down at the water, not fighting it, not fighting her, not fighting anything. Just wondering, really, as he gazed down at the long line of big black boulders that reached all the way back to the sand. He’d never noticed them before.

All the way out to where Leo had almost drowned.

Melissa absolutely hated “first thing in the morning” conference calls with corporate in Philly. The worst part was schlepping all the way downtown to her office in order to take those calls—because nine in the morning on the East Coast meant six in the morning for Washington State. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...