THE FIRST ELLEN THRUSH has probably been dead all this time—and it’s not that I don’t care, exactly. I care, I think. I’m curious, at least. But thank God, no one expects me to get too worked up about it. She vanished before I was born, and all I have of her is an old picture or two and her name. My mother gave it to me when I was born: two years, one month, and thirteen days after Ellen mailed a Christmas card to my grandmother. In it, she wrote that she was happy, and she wished the family a wonderful new year.

There’s evidence to suggest she didn’t mean the last part, but it’s not for me to say. Maybe she was a bigger person than I am.

Frankly, I’d be surprised.

We are too much alike, as my mother and grandmother have never failed to remind me. When I did good things—when I finished my master’s degree, when I bought my house with my own money—then I was so very much like my long-lost Aunt Ellen. She had such an independent spirit after all! But when I did things the Thrushes didn’t like, somehow it was still the same story: when I dropped out of my doctorate program, when I got a DUI, when I came home with a girl instead of a boy. Oh yes. So much like my no-good, pervert of an aunt, may she rest in peace wherever she lies.

That’s when they’d pretend that I never switched to using my middle name. They’d call me by her name, with a sneer just loud enough to be heard. Even after I got my sober-for-a-year chip. (I shouldn’t have bothered. I threw it away.) Even after I brought home another boy or two, like I was trying to maintain a balance on some ledger. It never seemed to matter.

So I don’t see the Thrushes very much—not anymore. I didn’t go missing like Aunt Ellen; I just quit coming home.

Plenty of people said that’s exactly what Ellen did; she ran away from home, if you can call it that when a woman’s an adult in her twenties. But I don’t believe it. Sure, I fantasized more than once about walking away from Thrush House myself, leaving behind everyone who ever called it home. Of course, I understand the urge to quit arguing, to quit participating in the endless escalation of whose feelings are hurt most, and why, and by whom. Absolutely, they are exhausting women who deserve one another.

I can truly imagine there’s a world where my aunt Ellen might have had it up to here, packed a suitcase, and rode off into the sunset with her thesis advisor slash girlfriend—an esteemed professor of women’s history at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

But not this world. I don’t believe that Ellen ran away, and I don’t believe that she’s alive anymore either.

I don’t believe she would have abandoned Judith.

The first time I met Judith, she said I could call her “Aunt Judy” if I wanted, but I wasn’t having it. This random woman was no old friend or near relation; she’d looked me up out of the blue after spotting my name on a form. By sheer coincidence, I was applying for a graduate program in history at the University of Florida, where she was working by then. I was hoping to pull together a thesis that made half an ounce of sense, and I wasn’t entirely sure it was worth the trouble.

I’d been waitlisted and then called up.

I’d been spotted by Dr. Judith Kane, notably less esteemed in some regards since she’d run off with one of her students in the 1970s—or that was the campus rumor, as I was to later learn. I could’ve confirmed it for every gossiping undergrad, but I restrained myself. No one needed to know that she ran away with my aunt Ellen.

By all reports, Ellen was a legend. She was also a hellion and a heathen, but Judith would be the first one to tell you that, smiling over a cigarette, beside a glass of wine, in front of the fireplace when we were supposed to be talking about Aphra Behn and Elizabeth Carey.

It was never weird, sitting in her living room, surrounded by books, notes, booze, and the vague confidence that I wasn’t going to finish my academic program any more than the first Ellen Thrush had ever finished hers. Our relationship was never inappropriate, either; though over time, I do admit I developed an attachment to Judith that might be described (by some nosy people, somewhere) as “unhealthy.” I looked up to her, in a way I’d never looked up to any other woman before—no relative, mentor, or anyone else. Judith is brilliant, you see. She is beautiful. She is plenty old enough to be my mother, and for a few years, she was the most important person in my life.

You could say I had a crush, though that wouldn’t quite be true. I didn’t want to fuck her; I wanted to be her.

Don’t worry. She didn’t want to fuck me, either. She just wanted to believe that some little piece of her beloved Ellen lived on, or that someone else remembered her—even someone who’d never met her.

“I do think she died before you were born,” she told me once.

“Because she would have never left you?”

She opened her mouth, and I thought she was going to say, “Yes, that’s why.” But she didn’t. She took another draw of smoke and said, “No real reason at all, but it’s very romantic, isn’t it? The thought that she died and you were born, and even your tragic family thought it meant something to give you her name. What if some other piece of her traveled with you? Some … awareness or spark of personality could’ve come along for the ride, following the name or following the next child to be born in a familiar family.”

She lost me there. “You know enough about the Thrushes to call them tragic, but not enough to know … well. If the consciousness of Ellen Thrush survived at all, on any plane, the last place she’d ever go is home. Trust me on that one.”

I remember how Judith had soured. “What if she was trying to … to …” Another sip.

Tobacco and wine. “Find her way back to me. What then.” She stared down at the smoldering stub that should’ve been put out already. She swapped it for the wine and gazed into it like she was an oracle, and the cheap grocery store red came from the omphalos of Delphi itself.

God, I’d felt like an asshole. I think I muttered something along the lines of, “There must have been an easier way,” but it wasn’t the right thing to say. There was no right thing to say.

Judith Kane did not really believe in reincarnation, anyway. Not like she believed in old poetry.

Anyway, I did leave the program, as anyone who knew me might have guessed. Eventually I left Florida, too. And Judith. It was a tearful parting, one that seemed so full of dramatic inevitability at the time—but was probably just a tantrum, in retrospect. Judith had wanted something I couldn’t give her, and someone I couldn’t be; and she knew before I even said so, that I was tired of reading about other people’s great works and felt the need to create my own.

It was an ambitious tantrum, but it never went anywhere. I never wrote the Great American Novel or even reviewed one. I didn’t get into hard-hitting journalism, or take any major stands against injustice, or do anything much to improve the world at large. I ended up an overloaded adjunct, teaching composition at the University of Tennessee. They’ll put it on my tombstone: “She taught freshmen the five-paragraph essay.” And that’s all, I guess.

At first, Judith and I stayed in touch. We had to, after all the vehement vows and clutched hands and carefully worded promises.

But time and distance did their thing.

In those early professional years, I was in over my head, juggling a teaching schedule that should’ve been illegal for its casual cruelty. I was abrupt. I had my head up my own ass, as she told me more than once.

She was somehow both distant and needy in phone calls, then letters, and then the occasional email. Each Christmas card felt more perfunctory, and in the end, I stopped sending cards to anyone—just to avoid sending one to her.

and making it seem personal.

I don’t know why it went strange that way. I don’t know if I regret it, or if it was only the best and most productive use of everyone’s time: for me to remove myself from a situation that felt, at times, like a spiraling dive into someone else’s life. Judith was the archivist of all things Ellen, dedicating closets and crates to the study of what used to be and what might have been. For every new hint or scrap, she would make room if she didn’t have room. (I think she’d always been making room for me—for exactly this reason.)

I couldn’t escape the first Ellen’s shadow, no matter how far I ran from our family. No matter how far I ran from our teacher.

Maybe it just wasn’t in the cards.

Or maybe I was wrong, and the timing was wrong too—because it’d been twelve years since I abandoned the graduate program and five years since I’d last heard from Judith when she sent me a new email. The subject line was cautiously cool: “I know it’s been a while, but I wanted to show you this.” Acknowledging that we hadn’t spoken. Hinting at something shared.

Damn, she was good.

“Must be something to do with Ellen,” I assumed out loud.

I didn’t open the email right away but left my desk to go make a cup of coffee. I wanted to have my hands full when I clicked to see what olive branch she was offering, if that’s what this was. She hadn’t wronged me and she didn’t owe me anything. If anyone owed anybody an olive branch, it was me—but I wasn’t sure. If I was, I wouldn’t have needed the coffee to steel myself against some apology or some request for an apology that was implied but never asked.

I shouldn’t have worried. Judith was all business—if that’s what the first Ellen had become to us.

I realize that this message comes out of the blue, but I wasn’t sure who else I ought to approach. I hope you won’t be upset or offended, and I pray that I’m not overstepping some unspoken boundary. I know that my Ellen was both what drew us together, and likely what pushed us apart. But she’s what we had in common, then

and now, and always.

I’m sure it won’t surprise you to know that I’ve always kept one eye on the internet with regards to Ellen and whatever became of her. Science marches apace and cold cases are revived every day. Why not hers? Why not some fresh bit of evidence, lost for the decades and spotted again free of context, until and unless I successfully connect the dots?

It’s always been a longshot, and I’m well aware that nothing is ever likely to come of such digital fishing, but something truly intriguing has come to my attention, and I wanted to bring it to yours.

In short, I’ve attached a link to a newspaper article—a little “local color” piece that recently appeared in the Chattanooga Times-Free Press. I cannot say and do not know if it’s a reference to our Ellen, but it’s certainly an intriguing set of coincidences, isn’t it? The dates work out nicely—or horribly, however you prefer to think of it—and it’s not so far away from where we last saw her.

Please, indulge me. Read the article and get back to me, if you would be so kind. I want a second opinion from someone who knows as much about the situation as I do. Am I reading too far into this? Am I finding hope where there’s nothing but a tragic old mystery? Dear God, they even lost this poor woman’s corpse … it’s not like there’s any closure waiting at the other end, even if it turns out that this is our Ellen.

I’d like to go find this town, Kate—this tiny, ridiculous town. It’s barely on Google Maps, just a wide spot in the road, as they say. But there’s a little hotel and what’s left of Main Street. Clearly, there are a few old timers still hanging around, willing to speak with the press. And someone, somewhere, who keeps leaving that spooky graffiti all over the damn place. In the same handwriting, even, after all these decades. The persistent vandal must be my age, at least. That’s a clue, isn’t it?

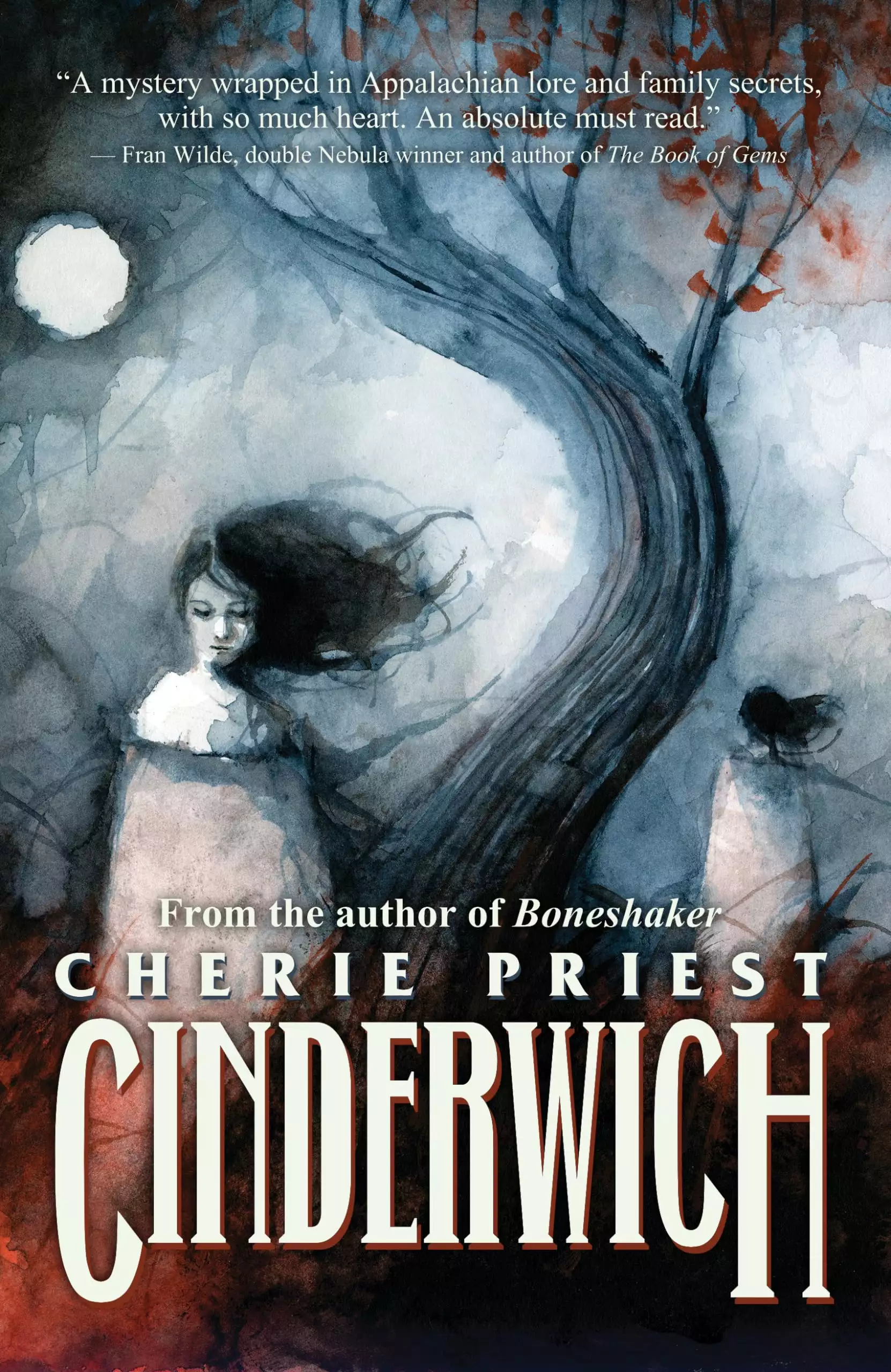

So yes, I’d like to visit Cinderwich, but I don’t wish to do so alone. Could I possibly persuade you to join me there? I’ll go with or without you, but I’d much rather have the company.

On a practical note, it would be helpful to have one of Ellen’s family members on hand; it might mean fewer awkward questions, in a rural southern place that might or might not be caught up to the 21st century when it comes to LGBTQIA+ normalcy and whatnot. (Unless I’m being ungenerous, which is always

possible.) If you’re the one leading the inquiries, no one will find it strange. That’s all I mean.

On a more personal note, I’ve missed you. I’d like to see you again. This will be an emotional and difficult trip for me, and I know you will understand better than anyone, despite the years and miles between us.

I’ll be flying into Chattanooga this Friday, and I have a room booked in Cinderwich at the Rockford Inn. At the risk of being presumptuous, I requested a room with two double beds, in case you will do me the kindness of joining me there. If you won’t, then I guess I’ve got plenty of room to unpack and spread out. But I’d rather have your presence.

She signed off with a simple, “Yours, Judith.”

The article link was attached beneath her signature. The headline read, “Decades Old Mystery Refuses to Die.” Ah, yes. Just a month until Halloween, so ’twas the season for such fluff pieces—in publications large and small, respected and frivolous.

I surrendered to the clickbait and loaded up the page.

“Who put Ellen in the blackgum tree?” That’s the question still being asked via spray-paint, in the tiny town of Cinderwich, Tennessee. It’s been 45 years since an unidentified woman’s body was found wedged into the fork of a tree where she’d been at rest for at least two or three years (according to estimates at the time). Trespassing children spied her dress and a single shoe. Police retrieved the corpse and sent it out for an autopsy. No cause of death was ever determined, and no one ever came forward to claim the woman’s remains. She had curly dark blonde hair and was approximately twenty years old. To date, her identity remains entirely unknown.

Or does it? One week after the mystery woman was removed from her resting place, a singular message

appeared on the side of a barn nearby: “Who put Ellen in the blackgum tree?”

No one has any good answer, least of all if the woman’s name was, in fact, Ellen. But the same query, written again and again in the very same handwriting, has appeared every year since 1979.most recently scrawled across the back of the town’s historic train station ...

The rest of the article was heavy on atmosphere, light on details.

As Judith had mentioned, the corpse had been lost to the sands of time and so had the autopsy report from the hospital in Chattanooga, but there had been a few theories regarding her identity. Someone said that she was a prostitute from Franklin who’d gone missing around that same time, but that woman had later turned up alive. Someone else was confident that she was the victim of a serial killer who’d never been caught. A third “expert” suggested that she might have been the daughter of a prominent politician who’d gone in search of an abortion and never made it back. (But that was a Sue Ellen, not an Ellen. Important distinction, in my opinion.)

But at the end of the

day, nobody had a clue who she was, how she died, or how she got in the blackgum tree.

No one except for the mystery vandal, if the graffiti wasn’t the work of some corny prankster.

The academic corner of my mind, the bit of me that still demanded citations for casual assertions, had some concerns about the story. There wasn’t much to suggest that it was true, in any version. Only the original news bulletins, some alleged scraps of paperwork from the coroner, and one page of a surviving police report suggested that the woman in the tree had ever existed at all.

Nothing but graffiti suggested that her name had been Ellen.

And the timing was only a coincidence … her body was found about eighteen months after my aunt Ellen disappeared. The description could’ve matched any woman of a similar age. By the time she was pulled from the tree fork, her weathered bones were covered in rags of dried flesh. Who could say for certain what she’d looked like in life?

It was an interesting story, I’d give it that. I wished I’d stumbled across it in my research days, or even as some passing article down an internet rabbit hole. ...