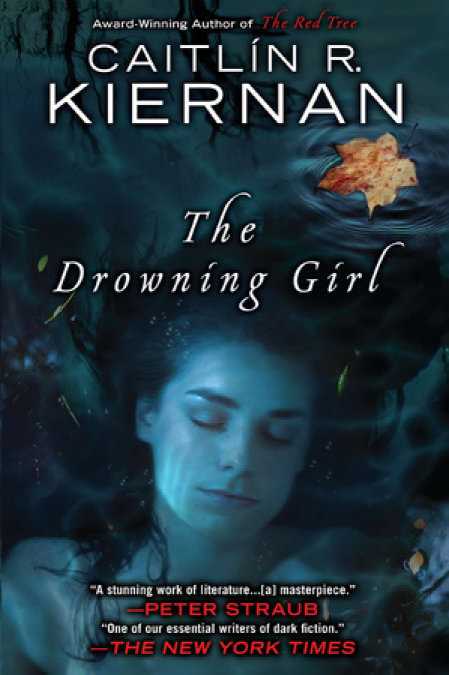

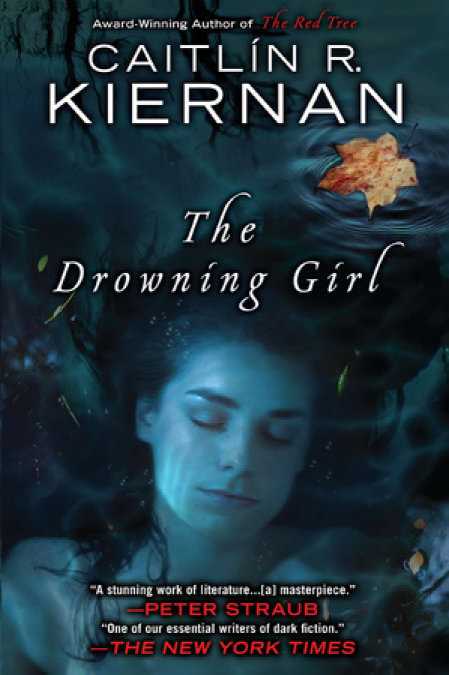

The Drowning Girl

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

“With The Drowning Girl, Caitlín R. Kiernan moves firmly into the new vanguard, still being formed, of our best and most artful authors of the gothic and fantastic—those capable of writing fiction of deep moral and artistic seriousness.”—Peter Straub

India Morgan Phelps—Imp to her friends—is schizophrenic. She can no longer trust her own mind, convinced that her memories have somehow betrayed her, forcing her to question her very identity.

Struggling with her perceptions of reality, Imp must uncover the truth about an encounter with a vicious siren, or a helpless wolf who came to her as a feral girl, or something that was neither of these things, but something far, far stranger…

Release date: March 6, 2012

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Drowning Girl

Caitlin R. Kiernan

“I’m going to write a ghost story now,” she typed.

“A ghost story with a mermaid and a wolf,” she also typed.

I also typed.

My name is India Morgan Phelps, though almost everyone I know calls me Imp. I live in Providence, Rhode Island, and when I was seventeen, my mother died in Butler Hospital, which is located at 345 Blackstone Boulevard, right next to Swan Point Cemetery, where many notable people are buried. The hospital used to be called the Butler Hospital for the Insane, but somewhere along the way the “for the Insane” part was dropped. Maybe it was bad for business. Maybe the doctors or trustees or board of directors or whoever makes decisions about such things felt crazy people would rather not be put away in an insane asylum that dares to admit it’s an insane asylum, that truth in advertising is a detriment. I don’t know, but my mother, Rosemary Anne, was committed to Butler Hospitalbecause she was insane. She died there, at the age of fifty–six, instead of dying somewhere else, because she was insane. It’s not like she didn’t know she was insane, and it’s not like I didn’t know, too, and if anyone were to ask me, dropping “for the Insane” is like dropping “burger” from Burger King, because hamburgers aren’t as healthy as salads. Or dropping “donuts” from Dunkin’ Donuts because donuts cause cavities and make you fat.

My grandmother Caroline—my mother’s mother, who was born in 1914, and lost her husband in World War II—she was also a crazy woman, but she died in her own bed in her own house down in Wakefield. No one put her away in a hospital, or tried to pretend she wasn’t crazy. Maybe people don’t notice it so much, once you get old, or only older. Caroline turned on the gas and shut all the windows and doors and went to sleep, and in her suicide note she thanked my mother and my aunts for not sending her away to a hospital for the mentally insane, where she’d have been forced to live even after she couldn’t stand it anymore. Being alive, I mean. Or being crazy. Whichever, or both.

It’s sort of ironic that my aunts are the ones who had my mother committed. I suppose my father would have done it, but he left when I was ten, and no one’s sure where he went. He left my mother because she was insane, so I like to think he didn’t live very long after he left us. When I was a girl, I used to lie awake in bed at night, imagining awful ways my father might have met his demise, all manner of just desserts for having dumped us and run away because he was too much of a coward to stick around for me and my mother. At one point, I even made a list of various unpleasant ends that may have befallen my father. I kept it in a stenographer’s pad, and I kept the pad in an old suitcase under my bed, because I didn’t want my mother to see it. “I hope my father died of venereal disease, after his dick rotted off” was at the top of the list, and was followed by lots of obvious stuff—car accidents, food poisoning, cancer—but I grew more imaginative as time went by, and the very last thing I put on the list (#316), was “I hope my father lost his mind and died alone and frightened.” I still have that notebook, but now it’s on a shelf, not hidden away in an old suitcase.

So, yeah. My mother, Rosemary Anne, died in Butler Hospital. She committed suicide in Butler Hospital, though she was on suicide watch at the time. She was in bed, in restraints, and there was a video camera in her room. But she still pulled it off. She was able to swallow her tongue and choke to death before any of the nurses or orderlies noticed what was happening. The death certificate says she died of a seizure, but I know that’s not what happened. Too many times when I visited her, she’d tell me she wanted to die, and usually I told her I’d rather she lived and get better and come home, but that I wouldn’t be angry if that’s really what she had to do, if she had to die. If there came a day or night when she just couldn’t stand it any longer. She said she was sorry, but that she was glad I understood, that she was grateful that I understood. I’d take her candy and cigarettes and books, and we’d have conversations about Anne Sexton and Diane Arbus and about Virginia Woolf filling her pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse. I never told Rosemary’s doctors about any of these conversations. I also didn’t tell them about the day, a month before she choked on her tongue, that she gave me a letter quoting Virginia Woolf’s suicide note: “What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that—everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.” I keep that thumbtacked to the wall in the room where I paint, which I guess is my studio, though I usually just think of it as the room where I paint.

I didn’t realize I was also insane, and that I’d probably always been insane, until a couple of years after Rosemary died. It’s a myth that crazy people don’t know they’re crazy. Many of use are surely as capable of epiphany and introspection as anyone else, maybe more so. I suspect we spend far more time thinking about our thoughts than do sane people. Still, it simply hadn’t occurred to me, that the way I saw the world meant that I had inherited “the Phelps Family Curse” (to quote my Aunt Elaine, who has a penchant for melodramatic turns of phrase). Anyway, when it finally occurred to me that I wasn’t sane, I went to see a therapist at Rhode Island Hospital. I paid her a lot of money, and we talked (mostly I talked while she listened), and the hospital did some tests. When all was said and done, the psychiatrist told me I suffered from disorganized schizophrenia, which is also called hebephrenia, for Hebe, the Greek goddess of youth. She—the psychiatrist—didn’t tell me that last part; I looked it up myself. Hebephrenia is named after the Greek goddess of youth because it tends to manifest at puberty. I didn’t bother to point out that, if the way I thought and saw the world meant that I was schizophrenic, the crazy had started well before puberty. Anyway, later, after more tests, the diagnosis was changed to paranoid schizophrenia, which isn’t named after a Greek god, or any god that I’m aware of.

The psychiatrist, a women from Boston named Magdalene Ogilvy—a name that always puts me in mind of Edward Gorey or a P. G. Wodehouse novel—found the Phelps Family Curse very interesting, because, she said, there’s evidence to suggest that schizophrenia may be hereditary, at least in some cases. So, there you go. I’m crazy because Rosemary was crazy and had a kid, and Rosemary was crazy because my grandmother was crazy and had a kid (well, several, but only Rosemary lucked out and got the curse). I told Dr. Ogilvy the stories my grandmother used to tell about her mother’s sister, whose name was also Caroline. According to my grandmother, Caroline kept dead birds and mice in stoppered glass jars lined up on all her windowsills. She labeled each jar with a passage from the Bible. I told the psychiatrist I’d suspect that my Great Aunt Caroline might have only suffered from a keen interest in natural history, if not for the thing with the Bible verses. Then again, I said, it might have been she was trying to create a sort of concordance, correlating specific species with scripture, but Dr. Ogilvy said, no, she was likely also schizophrenic. I didn’t argue. Rarely do I feel like arguing with anyone.

So, I have my amber bottles of pills, my mostly reliable pharmacopeia of antipsychotics and sedatives, which are not half so interesting as my great aunt’s bottles of mice and sparrows. I have Risperdol, Depakene, and Valium, and so far I’ve stayed out of Butler Hospital, and I’ve only tried to kill myself. And only once. Or twice. Maybe I have the drugs to thank for this, or maybe I have my painting to thank, or maybe it’s my paintings and the fact that my girlfriend puts up with my weird shit and makes sure I take the pills and is great in the sack. Maybe my mother would have stuck around a little longer if she’d gotten laid now and then. As far as I know, no one has ever proposed sex therapy as a treatment for schizophrenia. But at least fucking doesn’t make me constipated or make my hands shake—thank you, Mr. Risperdol—or cause weight gain, fatigue, and acne—thank you so much, Mr. Depakene. I think of all my pills as male, a fact I have not yet disclosed to my psychiatrist. I have a feeling she might feel compelled to make something troublesome of it, especially since she already knows about my “how daddy should die” list.

My family’s lunacy lines up tidy as boxcars: grandmother, daughter, the daughter’s daughter, and, thrown in for good measure, the great aunt. Maybe the Curse goes even farther back than that, but I’m not much for genealogy. Whatever secrets my great–grandmothers and great–great–grandmothers might have harbored and taken to their graves, I’ll let them be. I’m already sort of sorry I haven’t done the same for Rosemary Anne and Caroline. But they’re too much a part of my story, and I need them to tell it. Probably, I could be writing fabricated versions of them, fictional avatars to stand in for the women they actually were, but I knew both well enough to know neither would have wanted that. I can’t tell my story, or the parts of my story that I’m going to try to tell, without also telling parts of their stories. There’s too much overlap, too many occurrences one or the other of them set in motion, intentionally or unintentionally, and there’s no point doing this thing if all I can manage is a lie.

Which is not to say every word will be factual. Only that every word will be true. Or as true as I can manage.

Here’s something I scribbled on both sides of a coffeehouse napkin a few days back: “No story has a beginning, and no story has an end. Beginnings and endings may be conceived to serve a purpose, to serve a momentary and transient intent, but they are, in their fundamental nature, arbitrary and exist solely as a convenient construct in the mind of man. Lives are messy, and when we set out to relate them, or parts of them, we cannot ever discern precise and objective moments when any given event began. All beginnings are arbitrary.”

Before I wrote that and decided it was true, I would come into this room (which isn’t the room where I paint, but the room with too many bookshelves) and sit down in front of the manual typewriter that used to be Grandmother Caroline’s. The walls of this room are a shade of blue so pale that sometimes, in bright sunlight, they seem almost white. I would sit here and stare at the blue–white walls, or out the window at the other old houses lined up neatly along Willow Street, the Victorian homes and the autumn trees and the gray sidewalks and the occasional passing automobile. I would sit here and try to settle on a place to begin this story. I would sit here in this chair for hours, and never write a single word. But now I’ve made my beginning, arbitrary though it may be, and it feels about as right as I think any beginning ever will. It only seemed fair to get the part about being crazy out up front, like a disclaimer, so if anyone ever reads this they’ll know to take it with a grain of salt.

Now, also arbitrarily, I’m going to write about the first time I saw The Drowning Girl.

For my eleventh birthday, my mother took me to the museum at the Rhode Island School of Design. I’d told her I wanted to be a painter, so that year for my birthday she bought me a set of acrylics, brushes, a wooden palette, and a couple of canvases, and she took me to the RISD Museum. And, like I said, that day was the first time I saw the painting. Today, The Drowning Girl hangs much nearer the Benefit Street entrance than it did when I was a kid. The canvas is held within an ornately cared, gilded frame—same as all the others in that part of the Museum, a small gallery devoted to 19th–Century American painters. The Drowning Girl is small, measuring only about 8”x8” square. It hangs between William Bradford’s Arctic Sunset (1874) and Winslow Homer’s On a Lee Shore(1900). The gallery’s walls are a uniform loden green, which, I think, makes the antique golden frames seem somewhat less garish than they might otherwise.

The Drowning Girl was painted in 1898 by a Boston artist named Phillip George Saltonstall. Hardly anyone’s written about Saltonstall. He tends to get lumped in with the Symbolists, though one article called him a “late American disciple of the Pre–Raphaelite Brotherhood.” He rarely sold, or even showed, his paintings, and in the last year of his life burned as many as fifty in a single night. Most of the few that survive can be found scattered about New England, in private collections and art museums. Also, one hangs in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and another in Atlanta’s High Museum. Saltonstall suffered from seizures, insomnia, and chronic depression, and he died in 1907, at the age of thirty–nine, after falling from a horse. No one I’ve read says whether or not it was an accident, that fall, but probably it was. I could say he was a suicide, but I’m biased, and it would only be speculation.

As for the painting itself, The Drowning Girl was done mostly in somber shades of green and gray (and so seems right at home hanging on those loden walls), but with a few contrasting counterpoints—muted yellows, dirty–white shimmers, regions where the greens and grays sink into blackness. It depicts a young girl, entirely naked, possibly in her early twenties, but maybe younger. She’s standing ankle deep in a forest pool almost as smooth as glass. The trees press in close behind her, and her head is turned away from us, as she glances back over her right shoulder, into the forest, towards the shadows gathered below and between those trees. Her long hair is almost the same shade of green as the water, and her skin has been rendered so that it seems paradoxically jaundiced and imbued with some inner light. She’s very near the shore, and there are ripples in the water at her feet, which I take to mean she’s only just stepped into the pool.

I typed pool, but, as it turns out, the painting was inspired by a visit Saltonstall made to the Blackstone River in southern Massachusetts during the late summer of 1894. He had family in nearby Uxbridge, including a paternal first cousin, Mary Farnum, with whom he appears to have been in love (there’s no evidence the feelings were reciprocal). There’s been some conjecture that the girl in the painting is meant to be Mary, but if that’s the case, the artist never said so, or if he did, we have no record of it. But he did say the painting began as a series of landscape studies he made at Rolling Damn (also known as Roaring Dam, built in 1886). Above the dam, the river forms a reservoir that once served the mills of the Blackstone Manufacturing Company. The water is calm and deep, in sharp contrast to the rapids below the dam, flowing between the steep granite walls of the Blackstone Gorge, which are more than eighty–feet high in some places.

The title of the painting has often seemed strange to me. After all, the girl doesn’t appear to be drowning, but merely wading a little ways into the water. Still, Saltonstall has invested the painting with an undeniable sense of threat or dread. This may arise from the shadowy forest looming up behind the girl, and/or from the suggestion that something there has drawn her attention back to the trees. The snapping of a twig, maybe, or footsteps crunching in fallen leaves. Or a voice. Or almost anything else at all.

More and more, I’ve come to understand how the story of Saltonstall and The Drowning Girl is an integral part of my story—same as Rosemary Anne and Caroline are integral to my story—even if I won’t claim that it’s truly the beginning of the things that have happened. Not in any objective sense. If I did, I’d only be begging the question. Would the start be my first sight of the painting on my eleventh birthday, or Saltonstall’s creation of it in 1898? Or might it be better to start with the dam’s construction in 1886? Instinctively, I keep looking for that sort of beginning, even though I know better. Even though I know full well I can only arrive at useless and essentially infinite regressions.

That day in August, all those years ago, The Drowning Girl was hanging in another gallery, a room devoted to local painters and sculptors, mostly—but not exclusively—artists from Rhode Island. My mother’s feet were sore, and we were sitting on a bench at the center of the room when I noticed the painting. I can recall this all very clearly, though most of that day has faded away. While Rosemary sat on the bench, resting her aching feet, I stood gazing at Saltonstall’s canvas. Only, it seemed like I was staring into the canvas, almost the same as if it were a tiny window looking out on a soft–focus gray–green world. I’m pretty sure that was the first time a painting (or any other sort of two–dimensional image) struck me that way. The illusion of depth was so strong that I raised my right hand and pressed my fingers against the canvas. I believe I honestly expected them to pass right on through, to the day and the place in the painting. Then Rosemary saw me touching it and told me to stop, that what I was doing was against the museum’s rules, so I pulled my hand back.

“Why?” I asked her, and she said there were corrosive oils and acids on human hands that could damage an old painting. She said that whenever the people who worked in the museum needed to handle them, they wore white cotton gloves to protect the canvases. I looked at my fingers, wondering what else I could hurt just by touching it, wondering if the acids and oils seeping from my skin had done all sorts of harm to all sort of things without my knowing.

“Anyway, Imp, what were you doing, touching it like that?”

I told her how it had seemed like a window, and she laughed and wanted to know the name of the painting, the name of the artist, and the year it was done. All those things were printed on a card mounted on the wall beside the frame, and I read them off to her. She made notes on an envelope she pulled out of her bag. Rosemary always carried huge, shapeless cloth bags she’d sewn herself, and they bulged with everything from paperbacks to cosmetics to utility bills to grocery–store receipts (which she never threw away). When she died, I kept a couple of those bags, and I still use them, though I don’t think I kept the one she was carrying that particular day. It was made from denim, and I’ve never much liked denim. I hardly even wear blue jeans.

“Why are you writing that stuff down?”

“You might want to remember it some day,” she replied. “When something makes a strong impression on us, we should do our best not to forget about it. So, it’s a good idea to make notes.”

“But how am I supposed to know what I might want to remember and what I won’t ever want to remember?”

“Ah, now, that’s the hard part,” Rosemary told me and chewed her thumbnail a moment. “That’s the most difficult part of all. Because, obviously, we can’t waste all our time making notes about everything, can we?”

“Of course not,” I said, stepping back from the painting, but not taking my eyes off it. It was no less beautiful or remarkable for having turned out not to be a window. “That would be silly, wouldn’t it.”

“That would be very silly, Imp. We’d waste so much time trying not to forget anything that nothing worth remembering would ever happen to us.”

“So you have to be careful,” I said.

“Exactly,” she agreed.

I don’t recall much else about that birthday. Just my gifts and the trip to RISD, Rosemary saying I should write down what might turn out to be important to me someday. After the museum, we must have gone home. There would have been a cake with ice cream, because there always was, right up to the year she was committed. There wouldn’t have been a party, because I never got a birthday party. I never wanted one. We left the Museum, and the day rolled on, and midnight came, and it wasn’t my birthday again until I turned twelve. Yesterday, I checked a calendar online, and it informed me that the next day, the third of August, would have been a Sunday, but that doesn’t tell me much. We never went to church, because my mother was a lapsed Roman Catholic, and always said I’d be better off steering clear of Catholicism, if only because it meant I’d never have to go to the trouble of eventually lapsing.

“We don’t believe in god?” I might have asked her at some point.

“I don’t believe in god, Imp. What you’re going to believe, that’s up to you. You have to pay attention and figure these things out for yourself. I won’t do it for you.”

That is, if this exchange ever actually occurred. It almost seems that it did, almost, but a lot of my memories are false memories, so I can’t ever be certain, one way or the other. A lot of my most interesting memories seem never to have taken place. I began keeping diaries after they locked Rosemary up at Butler and I went to live with Aunt Elaine in Cranston until I was eighteen, but even the diaries can’t be trusted. For instance, there’s a series of entries describing a trip to New Brunswick that I’m pretty sure I never took. It used to scare me, those recollections of things that never took place, but I’ve gotten used to it. And it doesn’t happen as much as it once did.

“I’m going to write a ghost story now,” she typed, and that’s what I’m writing. I’ve already written about the ghosts of my grandmother, my mother, and my great–grandmother’s sister, the one who kept dead animals in jars labeled with scripture. Those women are all only ghosts now, and they haunt me, just the same as the other ghosts I’m going to write about. Same as I’m haunted by the specter of Butler Hospital, there beside Swan Point Cemetery. Same as my vanished father haunts me. But, more than any of these, I’m haunted by Phillip George Saltonstall’s The Drowning Girl, which I’d have eventually remembered even if my mother hadn’t taken the time that day to make notes on an envelope.

Ghosts are those memories that are too strong to be forgotten for good, echoing across the years and refusing to be obliterated by time. I don’t imagine that when Saltonstall painted The Drowning Girl, almost a hundred years before I saw it for the first time, he paused to consider all the people it might haunt. That’s another thing about ghosts, a very important thing—you have to be careful, because hauntings are contagious. Hauntings are memes, especially pernicious thought contagions, social contagions that need no viral or bacterial host and are transmitted in a thousand different ways. A book, a poem, a song, a bedtime story, a grandmother’s suicide, the choreography of a dance, a few frames of film, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a deadly tumble from a horse, a faded photograph, or a story you tell your daughter.

Or a painting hanging on a wall.

I’m pretty sure that Saltonstall was, in fact, only trying to exorcise his own ghosts when he painted the nude woman standing in the water with the forest at her back. Too often, people make the mistake of trying to use their art to capture a ghost, but only end up spreading their haunting to countless other people. So, Saltonstall went to the Blackstone River, and he saw something there, something happened there, and it haunted him. Then, later on, he tried to make it go away the only way he knew how, by painting it. It wasn’t a malicious act, the propagation of that meme. It was an act of desperation. Sometimes, haunted people reach a point where they either manage to drive away the ghosts or the ghosts destroy them. What makes all this even worse is that it usually doesn’t work, trying to drag the ghosts out and seal them up tight where they can’t hurt us anymore. I think, mostly, we only spread them, when we try to do that. You make a copy, or transmit some infinitesimal part of the phantom, but most of it stays dug so deeply into your mind it’s never going anywhere.

Rosemary never tried to teach me to believe in a god or sin, in Heaven or Hell, and my own experiences have never led me there. I don’t think I even believe in souls. But that doesn’t matter. I do believe in ghosts. I do, I do, I do, I do believe in ghosts, just like the Cowardly Lion said. Sure, I’m a crazy woman, and I have to take pills I can’t really afford to stay out of hospitals, but I still see ghosts everywhere I look, when I look, because once you start seeing them, you can’t ever stop seeing them. But the worst part is, you accidentally or on purpose start seeing them, you make that gestalt shift that permits you to recognize them for what they are, and they start to see you, too. You look at a painting hanging on a wall, and all at once it seems like a window. It seems so much like a window that an eleven–year–old girl tries to reach through it to the other side. But the unfortunate thing about windows is most of them work both ways. They allow you look out, but they also allow anything else that happens past to lookin.

I’ve gotten ahead of myself. Which means I need to stop, and go back, and set aside all this folderol about memes and ghosts and windows, at least for now. I need to go back to that night in July, driving alongside the Blackstone River not far from the spot that inspired Saltonstall to paint The Drowning Girl. Back to the night I met the mermaid named Eva Canning. But, also, back to that other night, the snowy night in November, in Connecticut, when I was driving through the woods on a narrow chip–and–tar road, and I came across the girl who was actually a wolf, and who may have been the same ghost as Eva Canning, and who’d inspired another artist, another dead man, a dead man whose name was Albert Perrault, to try and capture her likeness in his work.

And what I said earlier about the girlfriend who puts up with all my weird shit . . . that was sort of a lie, because she left me not long after Eva Canning showed up. Because, finally, the weird shit just got too weird. I don’t blame her for leaving, though I miss her and wish she were still here. Regardless, the point is, it was a lie, pretending she’s still with me. I said there’s no reason doing this thing if all I can manage is a lie.

So I have to watch for that.

And I have to choose my words carefully.

In fact, I find that I’m quickly, unexpectedly coming to realize that I’m trying to tell myself a story in a language that I’m having to invent as I go along. If I’m lazy, if I rely too heavily on the way anyone else would tell this story—anyone else at all—it’ll look ridiculous. I’ll be horrified or embarrassed by the sight of it, the sound of it. Or I’ll be horrified and embarrassed, and I’ll give it up. I’ll stash it away in a disused suitcase beneath my bed and never reach the place that will, arbitrarily, turn out to be the end. No, not even the end, but just the last page that I’ll write before I can stop telling this story.

I have to be careful, just like Rosemary said. I have to stop, and take a step back.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...