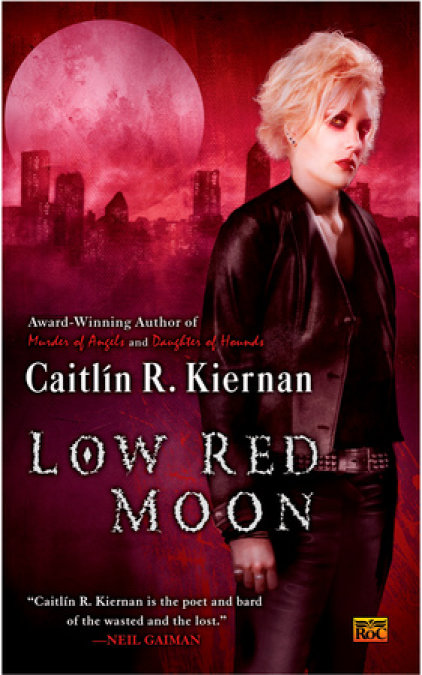

Low Red Moon • Copyright 2003 by Catlin R. Kiernan • 0-451-45948-2 • Roc Trade

Deacon had been sober for almost four months when Chance sold her grandfather’s big house, the tall white house overlooking the dingy gray carpet of Birmingham from the side of Red Mountain. The place where she’d lived most of her life, since her parents died when she was barely five years old and her grandparents took her in. The little attic bedroom that Chance had been unwilling to vacate even after they were married, never mind they had the whole house to themselves, her grandfather dead three years, and sometimes Deacon thinks she only married him because she couldn’t stand the thought of living in that house alone with the ghosts of her grandparents.

He made the mistake of saying that once—“Sometimes I think you only married me so you wouldn’t be alone,” reckless words he should have always kept to himself, but that was one of the endless, thirsty days when he could think of nothing but having a drink, just one drink, one very small goddamned drink. The anger and desperation building up inside him all day long, piling up like afternoon storm clouds on a sizzling summer day. And finally Chance had done or said something to piss him off, something inconsequential, something he’d forget a long, long time before he would ever forget the way she turned and stared at him with her hard green eyes. Even his thirst shriveling at the look she gave him with those eyes, the look that said I can leave you anytime I want, Deacon Silvey. Don’t you ever think I can’t.

He apologized and spent the rest of the day alone in the basement, banging about uselessly with a crescent wrench, pretending to work on the house’s leaky copper plumping. Those ancient pipes one of the reasons that Chance finally gave him for wanting to sell the place, the pipes and the furnace that rarely worked, the termites that were eating the back porch, the roof that needed reshingling, property taxes and the grass that Deacon couldn’t be bothered to mow. Her dissertation finally finished and there’d been a good job waiting for her at the university, an assistant professorship in the geology department.

“I just don’t want to have to worry about the place anymore,” she said one morning at breakfast and Deacon watched her silently across the kitchen table, uncertain how much of this was his decision to make, and what, if anything, he ought to say.

“I don’t know how Granddad kept it together all that time. I feel like it’s about to come crashing down around my ears.”

“It’s not that bad,” Deacon said and she shook her head and stared out the window at the weedy backyard.

“It’s bad enough.”

Deacon sipped at his scalding black coffee, waiting for her to say something else, waiting for his cue to say anything useful.

“Alice wants me to look at some lofts down on Morris,” she said without taking her eyes off the window.

“You think we could afford that, I mean—”

“I’m making decent money now, and we should get a good price for the house. It wouldn’t hurt our savings account.”

And Deacon waited for her to say, You could get a job, but she didn’t, looked away from the backyard and took a bite of her toast and apple butter instead.

“I just don’t want you to do something you might wind up regretting,” he said. “I mean, this is your home. You’ve lived here all your life.”

“That doesn’t mean I have to live here the rest of my life.”

Deacon shook his head, already sorry that he’d said anything at all. “No, it doesn’t,” he agreed.

And so Chance sold the house, the house and half the things in it, antiques and her grandfather’s guns, and they moved downtown into a renovated warehouse at the eastern end of Morris Avenue. What the woman from the realty agency kept referring to as the “historic loft district,” though Deacon could remember when the long cobblestone street had been something else entirely. Not so long ago, the early ’90s, back when Morris was only a neglected patchwork of warehouses struggling to stay in business and abandoned buildings dating to the turn of the last century and before. A couple of gay bars and one punk hangout called Dr. Jekyll’s, a coffeehouse and The Peanut Depot, which sold freshly roasted peanuts in gigantic burlap sacks. A place where homeless men slept in doorways and built fires on the unused loading docks, and sensible people avoided the poorly lit avenue after dark. But most of that time had been scrubbed away to make room for offices and art galleries, apartments and condos for yuppies who wanted to flirt with city life without leaving the reliable provincialism of Birmingham behind.

“And what do you do, Mr. Silvey?” the real-estate agent asked him while Chance filled in the credit history on their application.

“Mostly I try to stay sober,” he replied and Chance glared at him from the other side of the room.

A nervous little laugh from the agent and then she coughed and smiled at him expectantly, suspiciously, waiting for the real answer, and he wanted to take Chance and drive back to the big white house on the other side of town. Wanted to tell this woman she could go straight to hell and take her “historic loft district” with her. And who cared if the pipes leaked or there was no heat in the winter, so long as they didn’t have to answer questions from the likes of her.

“Deke’s thinking of going back to school soon,” Chance said before he could make things worse, and the woman’s face seemed to brighten a little at the news.

“Is that so?” she asked him and he nodded, even though it wasn’t.

“Deke was at Emory for two years,” Chance said, looking back down at the application, filling in another empty space with the ballpoint pen the real-estate agent had given her.

“Emory,” the woman repeated approvingly. “Were you studying medicine, Mr. Silvey, or law?”

“Philosophy,” Deacon answered, which was true, a life he’d lived and lost what seemed like a hundred years ago, before the booze had become the only thing that got him from one day to the next, before he’d come to Birmingham looking for nothing in particular but a change of scenery.

“Well, that must be very interesting,” the woman said, but the doubt was creeping back into her voice.

“I used to think so,” Deacon said. “But I used to think a whole lot of silly things,” and then he excused himself and waited downstairs behind the wheel of Chance’s rusty old Impala while she finished. He smoked and listened to an ’80s station on the radio, Big Country and Oingo Boingo, trying to decide whether he should just cut to the chase and take the bus home instead. When Chance came downstairs with the real-estate agent she was smiling, wearing her cheerful mask until the woman drove away in a shiny, black Beemer and then the mask slipped and he could see the anger waiting for him underneath. Chance didn’t get into the car, stood at the driver’s-side door and stared down Morris towards the train tracks that divided the city neatly in half.

“Go ahead,” he said. “Unload on me. Tell me what an asshole I am for queering the deal.”

“Deke, if you don’t want to do this, why the fuck don’t you just say so and then we can stop wasting our time?”

Deacon turned off the radio and leaned forward, resting his forehead against the steering wheel.

“All right. I don’t want to do this.”

“Shit,” she hissed, and he shut his eyes, trying not to think about how much easier all of this would be if he were only a little bit drunk. “Why the hell didn’t you say so before?”

“I didn’t want to piss you off.”

Chance laughed, a hard, sour sort of laugh, and kicked the car door hard enough that Deacon jumped.

“I don’t want to live in that house anymore, Deke. There are way too many bad memories there. I need to start over. I need to start clean.”

“I just wish you’d slow down, that’s all. I feel like we’re rushing into this.”

“Well, after the way you behaved up there, I expect you’ll be getting your wish.”

And Deacon didn’t say anything else, slid over to the passenger’s side and neither of them said another word while Chance drove them back to the house, and, as it turned out, he didn’t get his wish. Their application was approved three days later and Chance put the house that her great-grandfather had built up for sale. A month later the house sold, the house and its acre and a half of land, and the week after that they found out she was pregnant.

Through the library doors and past the winding marble stairs that lead up to the mezzanine, past the marble statue balanced on its marble column, headless angel, armless angel, and Deacon follows the short hallway back to the pay phones. A quarter just to get a dial tone and then he punches 411 and tells the operator he needs to place a collect call to Detective Vincent Hammond, Atlanta PD, Homicide Division, so she transfers him to an Atlanta operator. A long moment of clicks and static across the line, and Deacon waits and watches the towering, gold-framed portrait of George Washington hung on the wall opposite the hallway’s entrance. Washington stares back with his ancient, oil-paint eyes that are neither kind nor cruel, the unflinching face of authority and history, and after just a few seconds of that Deacon looks down at the scuffed toes of his shoes instead.

“Is anyone there?” Deacon asks the phone and “Just one moment, please, sir,” the Atlanta operator says impatiently and then a phone begins to ring at the other end.

“This is Hammond,” the man who answers the phone says in a smoky, tired voice, gravel voice, and just hearing him again, Deacon can smell the menthol Kools that dangle perpetually from Vince Hammond’s thin lips.

“You did this,” Deacon says. “You’re the one that told them where to find me.”

A pause and “Deke?” the cop asks, trying to sound confused or surprised, but Deacon knows it’s just an act. “Hey, bubba, is that really you? Goddamn. I haven’t heard from you in a coon’s age.”

“Don’t ‘hey, bubba’ me, you sonofabitch. You did it, didn’t you? You fucking knew I didn’t want any more of this crazy shit in my life and you did it anyway.”

“Yeah, well, let’s just say I owed someone a favor.”

Deacon wipes at his face, at flop sweat and the pain piling up higher and higher behind his eyes. Really no point in any of this, the call to Hammond, the accusations and anger, because the damage is done now and there’s no undoing it.

“Just calm down, bubba. You guys have a bad one over there. They needed some help.”

Deacon takes a deep breath, holds it, and glances back at George Washington; serene, certain George in his justaucorps and white wig, and Deacon exhales very slowly.

“I’m married, man,” he says. “I have a pregnant wife. I’m doing everything I can to stay sober. I can’t have this sort of shit in my life anymore.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know that. Congratula—”

“You could have fucking asked. You could have called me first and asked.”

“And you would’a told me to fuck off, right? Look, I just thought maybe you could help those boys out down there, that’s all. This one’s something special, Deke, something bad.”

“Yeah, and that’s exactly why it’s not my goddamn problem.”

“Good to know you’re still the same philanthropic soul I remember from the old days.”

“Fuck you, Hammond,” Deke growls into the receiver, raising his voice and a passing librarian scowls at him.

“Just don’t do it again, okay? Don’t ever do it again, do you understand me?”

“You have a gift, Deke—”

“I have a wife,” and he hangs up and stands glaring at the phone, waiting for his heart to stop racing, for the fury to drain away and leave him with nothing worse than the headache and his thirst.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved