- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

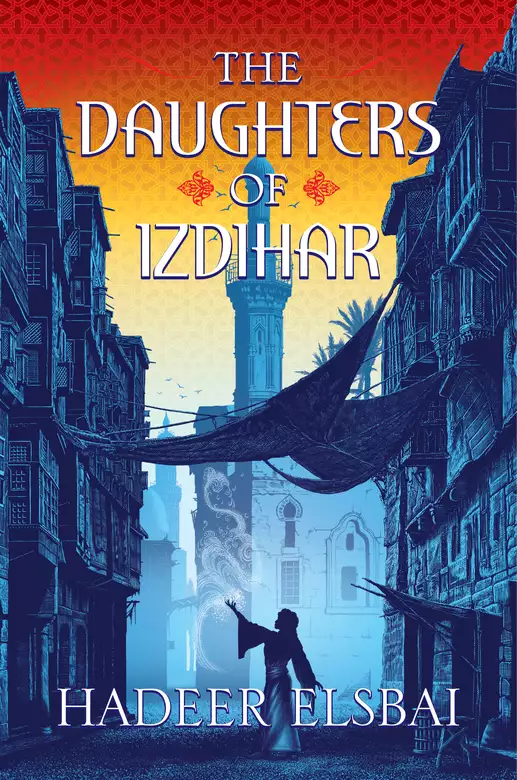

From debut author Hadeer Elsbai comes the first book in an incredibly powerful new duology, set wholly in a new world, but inspired by modern Egyptian history, about two young women—Nehal, a spoiled aristocrat used to getting what she wants and Giorgina, a poor bookshop worker used to having nothing—who find they have far more in common, particularly in their struggle for the rights of women and their ability to fight for it with forbidden elemental magic

As a waterweaver, Nehal can move and shape any water to her will, but she’s limited by her lack of formal education. She desires nothing more than to attend the newly opened Weaving Academy, take complete control of her powers, and pursue a glorious future on the battlefield with the first all-female military regiment. But her family cannot afford to let her go—crushed under her father’s gambling debt, Nehal is forcibly married into a wealthy merchant family. Her new spouse, Nico, is indifferent and distant and in love with another woman, a bookseller named Giorgina.

Giorgina has her own secret, however: she is an earthweaver with dangerously uncontrollable powers. She has no money and no prospects. Her only solace comes from her activities with the Daughters of Izdihar, a radical women’s rights group at the forefront of a movement with a simple goal: to attain recognition for women to have a say in their own lives. They live very different lives and come from very different means, yet Nehal and Giorgina have more in common than they think. The cause—and Nico—brings them into each other’s orbit, drawn in by the group’s enigmatic leader, Malak Mamdouh, and the urge to do what is right.

But their problems may seem small in the broader context of their world, as tensions are rising with a neighboring nation that desires an end to weaving and weavers. As Nehal and Giorgina fight for their rights, the threat of war looms in the background, and the two women find themselves struggling to earn—and keep—a lasting freedom.

Supplemental enhancement PDF accompanies the audiobook.

Release date: January 10, 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Daughters of Izdihar

Hadeer Elsbai

Nehal

Nehal Darweesh wanted to spit fire, but unfortunately she did not have that particular ability. Instead, she pulled out the liquid contents of a glass of water and separated them into rather large and ungainly droplets, much to the irritation of her mother, Shaheera, who found herself the unfortunate target of the storm.

Shaheera was leaning against a vanity laden with various concoctions of oils and perfumes. Her arms and legs were both tightly crossed, her forehead slowly setting into an even tighter scowl. Her corkscrew curls, which Nehal had inherited, were pulled back into a neat bun and oiled to a perfect sheen. Slowly, she began to tap her foot in warning.

Finally, when Nehal’s rain began to pool at Shaheera’s feet, Shaheera clapped her hands together and snapped, “Enough!”

Nehal did not look at her mother, nor did she spare a glance for the seamstress at her feet, who was doing her best to write down Nehal’s measurements while politely ignoring the gathering storm in the room. Instead, Nehal stared out her veranda, which led directly to a white-sand beach and an expanse of glittering blue ocean. The veranda doors were open, as they nearly always were, bringing forth a warm salt-spray breeze and the humming melody of waves.

“Nehal.”

She could practically hear her mother’s teeth grinding together. With a pointedly loud sigh, Nehal closed her eyes, and the fat droplets returned to their glass, though the puddle on the floor remained; Nehal was nowhere near skilled enough to extract water from a rug. Still, she continued to ignore her mother, who had now begun to pace

back and forth around her, skirting the edge of the large four-poster bed behind them.

“You would think we were sending you off to be executed, not married to one of the wealthiest men in all of Ramsawa,” muttered Shaheera. “And you’ve met him; you said he was nice, that you liked him—”

Nehal could keep quiet no longer. “That was before I knew I was being sold off to him!”

The seamstress, a tiny woman of about forty, shot up, sensing the fight’s escalation. With a halting look between mother and daughter, the seamstress said, “I’ve finished, my lady. Once I’ve completed all the adjustments, the wedding attire will be ready in a fortnight.”

“Excellent,” said Shaheera icily. “Thank you. You may go.” She did not even glance at the seamstress. Her gaze remained fixed on her daughter, who was now glaring back with equal fierceness. The two stared at each other silently, a battle of wills reminiscent of their many arguments, until the poor seamstress scurried away and closed the bedroom door behind her.

“This is unjust, Mama!” Nehal burst out. “You and Baba always promised I could choose my own husband, just as Nisreen did.”

Shaheera pinched the bridge of her nose. “Your sister found herself an excellent match. You, on the other hand, want to run off and be a soldier—”

“It’s an honorable profession,” Nehal protested.

“Honor does not pay debts,” snapped Shaheera. “And women don’t become soldiers. I’ve had enough of this nonsense. We’ve had the same conversation every day for a month—”

“Because you refuse to listen!” Nehal fumed. She picked up the periodical lying on her bed; the words The Vanguard were emblazoned across the front in bold, black calligraphy. Smaller text below read A Publication of the Daughters of Izdihar, and beneath that was a black-and-white photographic print of a young woman holding up a sign that read VOTES FOR WOMEN!

“If you would just read it—”

“Why would I need to read it when you’ve already told me everything it says?” Shaheera affected a mocking tone in a poor imitation of her daughter. “‘Ramsawa’s newly minted Ladies Izdihar Division! The first all-female military division in history—’”

“Because you don’t actually listen to me, clearly,” said Nehal irritably. “It’s the Academy that comes first; what’s wrong with going to school?”

“It’s not, as you so innocently phrase it, just school,” said Shaheera. “It’s a Weaving Academy—”

“What’s wrong with learning to be a weaver—”

“What’s wrong is that you are neither a soldier nor a street performer,” Shaheera snapped. “You’re a highborn lady, and you need to act like one. Not to mention this is skirting the bounds of the law and religion. An impressive feat.”

“It’s a government initiative,” said Nehal, “so they’re hardly skirting laws. And as for religion, I know for a fact you and Baba don’t give a donkey’s ass about the Order of the Tetrad—”

Shaheera clapped her hands thrice. “Language!” she snapped. “You are a Lady of House Darweesh, not a street urchin, and I’ll not have you act like one in this house.”

If I were a street urchin at least I’d be able to do whatever I want, Nehal thought. But that did not seem like something she ought to say out loud. “Mama . . .”

“All right, regale me then, Nehal. What’s your grand plan?”

In an uncharacteristic show of foresight, Nehal paused to consider her words. “I attend the Alamaxa Academy of the Weaving Arts. As an accomplished weaver, I’m recruited to join the Ladies Izdihar Division. I fight to bring honor to family and country.”

Shaheera rolled her eyes. “Ah, yes, my daughter, a foot soldier engaged in petty border skirmishes, in a women’s division no less. How honorable.”

Nehal groaned and turned away from her mother. She wanted nothing more than to march straight down to Alamaxa and enroll in the Academy herself, but as a woman, she could not join without a male guardian’s consent, which her father patently refused to give. It was one of the many infuriating ways in which Ramsawa insisted on infantilizing women.

There was also the matter of tuition: the Academy, newly reopened two years ago, and allowing entry to women only just this year, was free for men to attend, but women were required to pay tuition, which was exorbitant. And the Darweesh family was, as Nehal had recently discovered, in

I sit quietly while my daughter gets herself killed? You’re a highborn lady, so leave the soldiering to the rabble.”

“Tefuret help me,” muttered Nehal. But invoking the Lady of Water had done little to help Nehal thus far, and she had invoked her often. The gods did not tend to respond to their supplicants, even those they had gifted with weaving.

“Don’t be melodramatic,” said Shaheera in exasperation. “Do you know how sought-after the Baldinottis are? How many girls would be desperate for this opportunity?”

“If war does come, wouldn’t my abilities be more useful on the battlefield?” said Nehal. “I could make a difference to the outcome of—”

“You have a very overinflated opinion of yourself, Nehal,” interrupted Shaheera. “You need only worry about making a difference to your husband’s household.”

Nehal scowled, turned her back on her mother, and began to undress. She thought back to her meeting with Niccolo Baldinotti, barely a month ago. His unusual coloring made him stand out in her memories. Most Talyanis were practically indistinguishable from Ramsawis, if slightly paler, and the majority had intermarried into the Ramsawi population and taken on their traits, but Nico was blond and blue-eyed, unlike anyone Nehal had seen before. They had spoken only briefly, and he had seemed rather good-natured. Unlike most men, he had been amused rather than disapproving when she had swirled the sharbat in his glass into a miniature whirlpool.

But once Nehal was firmly in the grip of marriage, the law would make Niccolo her guardian, making it necessary to obtain his permission to attend the Academy, join the army, or, indeed, do much of anything at all. And why would any newlywed, even one who seemed moderately progressive, give his new wife permission to leave him?

What was Nehal to suffer, in the end? She would be denied her own personal happiness, of course, denied the chance to discover the fullest potential of her waterweaving abilities, but there were many who would envy her such a life. Her own happiness apparently meant very little when compared to her family’s lofty reputation.

Nehal finally slipped out of her many layers of suffocating fabric. The ocean sparkled in the distance, the waves calling to her. In Alamaxa, a desert city, there would be no ocean. There was the River Izdihar, of course, the beating heart that bisected the entirety of Ramsawa, but it

would not be the same as the endless expanse of blue sea Nehal was accustomed to swimming in nearly every day.

There was no point in bringing this up. Her mother wouldn’t understand; no one in her family could. Nehal was the only weaver in her entire extended family, and when they weren’t teasing her for her abilities, or her lack of control over them, they were simply indifferent. When the Alamaxa Academy had reopened after nearly two hundred years of being shuttered, Nehal had watched with envy as men flocked to its doors. Then came the announcement that women could finally attend, and Nehal rejoiced, only to have this marriage sprung on her. Her one opportunity to finally learn more about the abilities the gods had chosen to give her had slipped through her fingers like the water she desperately yearned to control.

She might have finally had a chance to live among others who understood what it meant to hold this strange, rare power that had been equally scorned and feared since the Talyani Disaster. Instead, she was to be sold off into marriage to a man she barely knew.

With a growl, Nehal kicked the foot of her bed, causing the entire thing to rattle.

Shaheera glared at her daughter. “Nehal—”

But Nehal no longer had any desire to listen to another word from her mother. She walked out through the veranda doors onto the sand, which was hot enough to sting the bare soles of her feet, and marched toward the ocean.

Giorgina

Giorgina Shukry was having a particularly unpleasant day.

It had begun with the weather. A brief but powerful dust storm had overtaken Alamaxa, slamming into Giorgina as she walked to work. She narrowed her eyes against the storm and blindly made her way to the nearest establishment for shelter, finding herself in an expensive teahouse that demanded she purchase a drink in order to remain on the premises.

Giorgina pleaded with the owner. “But—” She gestured helplessly toward the window, against which gusts of sand-laden wind were audibly slamming.

The owner only looked her up and down, taking in her cheap galabiya and faded black shawl, and said tersely, “Either buy something or leave.”

After purchasing an exorbitantly priced drink, Giorgina settled onto a plump cushion by the window and waited for the storm to pass. It raged loudly for some time, until the air turned a sickly red-brown, and eventually the sheltered teahouse grew stuffy and humid.

She was uncomfortably hot and had spent money she could not afford to lose, but even worse, this unfortunate detour meant Giorgina was late to relieve Anas of his shift. Anas, her boss of two years now, owned a tiny but oft-frequented bookstore that made most of its revenue off school textbooks and newspapers. He was a skinny, middle-aged man with a pointed face and sharp eyes, which he turned on Giorgina the moment she walked through the door, dusty and sweaty.

She tried to explain about the dust storm, which Anas might not have seen through the windows that were entirely

concealed by books, but before she could utter a single word, Anas snapped, “If you can’t show up on time, what is the point of you?”

“There was a dust storm,” Giorgina finally managed to say.

“I don’t care if Setuket himself descended upon the city and tore it in half,” Anas snapped. “I expect you here on time. Is that clear?”

Then, in a huff, Anas departed, leaving Giorgina with a rather large shipment of books that needed to be unpacked and cataloged. She thought this may have been his attempt at petty vengeance, but the shipment had arrived last night (though it would not have surprised Giorgina to learn that Anas prepared acts of petty vengeance in advance, just in case the need arose). She began the exhaustive process of unpacking and cataloging.

Giorgina did not particularly like Anas, and he did not seem to like her, but then, she didn’t think he truly liked anyone. He hardly ever spent time in his own bookshop when it was likely to be frequented by customers. Giorgina suspected this was because his demeanor caused most customers to flee, and that the main reason he had hired her—and hadn’t fired her—was to draw in more clientele that he would not need to interact with.

In fact, when Giorgina had responded to the advertisement posted in the newspaper, Anas had essentially told her so.

“A pretty face like yours would bring in customers,” Anas had mused, looking her up and down in a decidedly analytical fashion. “But do you have the pretty manners to match?”

He had tested her out for a day, lurking uneasily behind her as she dealt with a steady flow of customers. That same day, Anas hired her, but he had grown no warmer toward her in the two years they had known one another.

So, no, it was not particularly pleasant, but it was nothing compared to what Giorgina’s friends and sisters endured. They worked in dark factories, toiling beside hundreds of other women under the cacophonous grind of machinery, or mopped the floors in cheap coffeehouses, enduring the leers and unwanted advances of strange men. Compared to them, Giorgina worked in luxury. And she loved the books and the magazines and the newspapers, all freely available to her. She’d never be able to afford such things otherwise. She

could endure Anas’s unpleasantness in exchange for such good fortune.

Hours later, Giorgina was finally done cataloging the new arrivals. Relieved, she went to put the list of books in the cabinet they kept in the back, but on her way, she stumbled into a tower of books she had meticulously organized by subject yesterday morning, causing them to spill into another tower of books and crash to the floor in a chaotic heap. She heaved a sigh, then set to reorganizing the fallen towers.

By the time Anas returned for his second shift, Giorgina was exhausted, and her day was nowhere close to being finished. She re-wrapped her shawl around her head and left the bookshop to meet Labiba and Etedal. She hitched a ride in a mule cart for a piastre, but this only took her three-quarters of the way to her destination; no one would permit a mule cart to drive anywhere down Wagdy Street, where the lanes were clean and newly paved. Tetrad Gardens was one of Alamaxa’s wealthier districts, with its freshly painted buildings, cobbled streets, and modern boutiques and cafes. There was no way a mule cart would be tolerated among the richly embroidered palanquins making their way down the lanes.

Giorgina walked down one of these cobbled lanes, her eyes on her destination. King Lotfy Templehouse stood at the close of the dead-end lane: a massive edifice constructed entirely of yellow stone, heavily carved with complex geometric patterns. A large dome sat squarely in the center, surrounded by four minarets in each corner, one for each of the Tetrad. The entrance was a gigantic archway lined in latticework, flanked on either side by enormous statues of the gods: Rekumet and Setuket on the left, Nefudet and Tefuret on the right. All four sat upright on straight-backed thrones, their hands held palm up on their laps, their faces stern and commanding.

Giorgina had always found these facsimiles of the Tetrad intimidating. Even the small little statues people kept in their houses unsettled her somewhat, though she knew she had nothing to fear from entities that had withdrawn from the world. But according to the tales told by the Order of the Tetrad, when the gods had walked the earth, millennia ago, they’d possessed a capricious nature, and she wanted no part

of that. With a shudder, Giorgina turned away from the statues and headed into King Lotfy Templehouse.

Named after the first Ramsawi king, who had pulled together Upper and Lower Ramsawa into one unified nation, King Lotfy Templehouse was the grandest house of worship in Alamaxa. Giorgina had seen it before, but could never bring herself to go inside, though there were of course no rules keeping anyone out. No written rules, anyway—Ramsawa’s class stratification did its duty in keeping the likes of her out: King Lotfy Templehouse was known to be exclusively frequented by Alamaxa’s upper crust, of which Giorgina was decidedly not part.

Trying to remain inconspicuous, Giorgina walked toward the entrance hall, where dozens of Alamaxans were milling about. Everywhere Giorgina looked, she saw colorful embroidered robes and veils held down with ornate headdresses that looked like they amounted to Giorgina’s entire yearly salary. Ladies teetered delicately in pattens that kept their satin-clad feet off the ground as they sipped on sharbat that was offered to them by templehouse attendants.

To Giorgina this seemed more like a party than a religious observance; it was certainly much more festive here than the ramshackle templehouse her own family patronized. Her heart rattled at the prospect of having to walk among these people in her shabby galabiya, but most paid her no mind, and Giorgina walked purposefully toward a nondescript wooden door that opened into a poorly lit hallway so damp it made her shiver. Her footsteps echoed on cracked, uneven tiles as she made her way toward the annex, through which she found her way to the inner courtyard.

It was a modestly sized yard for such a gargantuan building, but no less pleasant for it: a star-shaped fountain sat in the center, filled with fragrant jasmine petals. Neatly trimmed hedges studded with pink flowers outlined the entire courtyard. In each of the four corners of the courtyard stood a tall palm tree, each heavy with ripe dates. Beneath the shade of one of these trees, sitting at a somewhat shoddy wooden table, were Labiba and Etedal.

When Labiba caught sight of Giorgina she stood and waved eagerly, her shawl slipping off her velvet-smooth black hair. Labiba threw her arms around Giorgina and kissed her cheeks in greeting; they’d seen each other several times a week for the last year, but Labiba was always enthusiastically affectionate. Labiba’s cousin Etedal, on the other hand, only glanced up, nodded, and resumed shuffling the papers in front of her.

In the sunlight, Labiba’s eyes were as bright as almond skins, a striking contrast against her deep umber skin. “It’ll be a lovely place to fundraise, won’t it?”

“I still can’t believe this Sheikh is letting you do this,” said Giorgina. She turned to look back, as though he might materialize. “Where is he, anyway?”

“He was just here.” Labiba looked toward the annex. “He had to step away for a moment—oh, there he is!”

The Sheikh striding toward them was handsome and young, younger than Giorgina thought Sheikhs could be; all the ones she had seen had been her father’s age. This man could not have been much older than Giorgina. He was also not alone: walking beside him, and deep in conversation with him, was an older man in robes richly embroidered. Giorgina blinked, momentarily disoriented.

“Isn’t that . . . the Zirani ambassador?” she asked.

Labiba followed her gaze. “Is it?”

Giorgina had seen that face in the papers: a gaunt yet coldly regal visage with deep-set eyes. She would have r

ecognized Naji Ouazzani anywhere.

He and the Sheikh paused at the threshold of the courtyard; Giorgina could not hear their conversation, but it appeared passionate and animated. After a moment, Naji Ouazzani nodded and walked away, leaving the Sheikh to approach them, his expression transformed into a smile.

“Peace be upon you, Miss Labiba,” he said jovially.

Labiba bowed her head. “Peace be upon you, Sheikh Nasef.” She turned to Giorgina. “This is my friend Giorgina. She’ll be helping us today.”

“May the Tetrad bestow peace upon you, Miss Giorgina.”

Giorgina smiled haltingly; she did not think she had ever been addressed so formally in her life.

Labiba continued, “I’ve told her all about you, and how you’re such an excellent friend to the Daughters of Izdihar!”

The Sheikh laughed, somewhat awkwardly. “I’m a friend to anyone who does good works, really . . .”

“It’s difficult to find a man who supports women getting the vote,” offered Giorgina.

Nasef nodded vigorously. “Of course! The Tetrad created all of us equally, after all—well, that is, except for weavers.” His lips pursed as he shook his head in obvious disapproval.

Giorgina couldn’t help glancing sidelong at Labiba, but Labiba’s smile was fixed in place, as bright as always.

“So, I’ll just go fetch my congregants, then, if you’re ready . . . ?” asked Nasef.

“Wonderful,” replied Labiba warmly. “Thank you so much, Sheikh Nasef.”

With a nod and a smile, the Sheikh departed.

When he was gone, Giorgina turned to Labiba and spoke in a low voice, out of Etedal’s hearing. “Does he have any idea you and I are weavers? Any at all?” Labiba knew about Giorgina’s abilities, but Etedal did not, and Giorgina would rather maintain that discretion.

Labiba shrugged. “It hasn’t come up.”

“And Malak? He must know about her.”

Labiba smiled somewhat guiltily. “I . . . may have implied that she tries very hard not to use her weaving. And that she runs the Daughters of Izdihar in part to atone for being cursed with weaving abilities. Or something like that. I’m fuzzy on the details.”

Giorgina raised her eyebrows, while Etedal, who had come around the table to join them, scoffed loudly.

“Other than his unfortunate views on weaving, he’s actually pretty enlightened,” insisted Labiba. “He’s been a great help organizing these drives. Do you think we’d get any money at all without him? He’s very dedicated to our cause.”

Etedal smirked. “That, and he likes you.”

“Oh, stop!”

“I’m telling you,” insisted Etedal. “If he doesn’t ask for your hand in marriage before year’s end, I’ll eat my shawl.”

Labiba winked. “I’ll hold you to that.”

Giorgina ignored the cousins’ banter. “You don’t think this is dangerous? Isn’t this the same Sheikh said to be involved with that cult, the Khopeshes of the Tetrad?”

Labiba waved her hand. “Oh, Giorgina, calling it a cult is so serious. It’s nothing like that.”

But Giorgina wasn’t sure the Khopeshes could be so easily dismissed. What Giorgina knew for certain about the Khopeshes of the Tetrad was that they were mostly clerics who lobbied Parliament to introduce anti-weaving laws. But it also was rumored some of their members were responsible for acts of anti-weaver violence that had made the papers in the previous months, not to mention a number of their members preached particularly extreme views on weavers.

“So he is involved?” asked Giorgina in disbelief.

Labiba shrugged, but she wouldn’t meet Giorgina’s eyes.

But something else was bothering Giorgina: it didn’t bode well that someone known to be as vehemently anti-weaving as Sheikh Nasef was so friendly with the Zirani ambassador. Tensions between Ramsawa and Zirana were high, and they were rooted in Ramsawa’s growing tolerance for weaving. The reopening of the Alamaxa Academy had clearly incensed the neighboring nation. Naji Ouazzani was supposed to be in Alamaxa to negotiate a peace treaty, so it was distressing to see him having such amiable conversations with a Sheikh known for his anti-weaving views.

But before she could consider asking Labiba and Etedal for their input, she heard the shuffle of footsteps; Nasef had returned. The three women hastily covered their faces with their veils so only their eyes were visible, then stood behind the table, where they had set up the donation box, the record b

ooks, and a sign-up sheet for their magazine, The Vanguard. Anonymity was the only way Giorgina could countenance being a part of the Daughters of Izdihar at all, so she made sure her face veil was held tightly in place.

Sheikh Nasef reentered the courtyard trailed by his wealthy congregants. It was only the third time the Daughters of Izdihar had attempted to fundraise in such a wealthy templehouse so openly; normally, Malak made sure they were relegated to only public streets. But Labiba had apparently made an impression on Sheikh Nasef, who had offered up the templehouse to her, and it was not an opportunity they could afford to turn down, no matter how nervous it made Giorgina.

There were more congregants than Giorgina had anticipated; about fifty of them hovered around Nasef. Most looked curious, some hesitant, and others still appeared hostile, their eyebrows drawn together in angry frowns. A throng of sneering teenage boys were pointing and snickering. Giorgina tensed, and felt a faint tremble below her feet, along with a slight pressure in the back of her head. She dug her nails into her palms.

Stay calm, she instructed herself.

Nasef led the group into the courtyard.

“Did you know the Daughters hold weekly literacy sessions for neighborhood girls?” asked Nasef loudly.

“What do street girls need to read for?” said one of the teenage boys, to a smattering of laughter from his peers.

Nasef frowned but chose to ignore the comment. “To those of you wondering what your donations would be funding, it is just that: literacy initiatives. Food drives. Soap drives. Support for single mothers—”

“And militaries made up of women,” interrupted one man, frowning. “A waste of time and resources.”

Giorgina peered at this mustachioed man, then widened her eyes in recognition. “Is that Wael Helmy? The owner of the Rabbani Club?”

Etedal sighed heavily. “Yes. We can’t go more than one month without some nonsense.”

Giorgina glanced at her uneasily, before turning back to Nasef, who was responding vigorously.

“The Izdihar Divi

sion is a single project belonging almost entirely to Malak Mamdouh, and the Daughters of Izdihar are more than just one woman—”

“I doubt that,” said Wael Helmy flatly.

An elderly couple wandered over to their table, distracting Giorgina from Nasef and Wael’s conversation. She listened as Labiba, with a beatific smile, took down their names and their rather sizable donations.

“You’re doing good work, my dears,” said the elderly woman. “It’s about time things change. Don’t listen to small minds.”

Beside her, her husband was nodding vigorously. The couple wandered away, clearing Giorgina’s view; Nasef was still engaged in conversation with Wael.

“I’m telling you, the Izdihar Division has nothing to do with the Daughters of Izdihar anymore,” Nasef was insisting.

“And can you guarantee they didn’t use any of these funds to spearhead that bill in particular?” demanded Wael. “Or to fund another one of Malak Mamdouh’s crazy ideas?”

A broad woman came up to Wael and put a hand on his arm. “My husband is just concerned about Malak Mamdouh’s influence, Sheikh. Of course we support your efforts to fight poverty, but what of Miss Mamdouh’s less savory endeavors? Her often uncouth behavior?”

At this, Etedal rose in her seat, despite Labiba’s whispered warnings. “What uncouth behavior?” demanded Etedal. “Say what you mean.”

Heedless of Labiba tugging on her galabiya, Etedal walked around the table until she was face-to-face with Wael’s wife. Giorgina gripped the edges of her chair, hard.

Wael’s wife seemed to hesitate, then said, “For instance, her rudeness to Parliament—”

“You don’t think you deserve to vote?” said Etedal. “To run for office?”

“My husband votes for me,” replied the other woman stiffly.

“That’s all well and good, Lady Rabab,” said Nasef gently. “But what of women with no husbands? Or women who disagree with their husbands? Isn’t it better that all women have a choice to exercise their vote, whether they do so or not, just as men are given the choice?” He gestured around him. “After all, do the Tetrad not equally share their duties? Nefudet and Tefuret are no lesser, for being women.”

One of the teenage boys spoke up. “You said it was blasphemy to compare yourself to the gods. You said only weavers do that.”

“It is blasphemy to claim we are created in their image, or to say that we deserve their abilities,” said Nasef. “For they are greater than we can ever be. It is not blasphemy to aspire to their models of behavior.”

The boy shrugged, then resumed whispering to his compatriots, who were all giving Giorgina and Labiba what looked to be conspiratorial looks. One of the boys even winked at Giorgina. She frowned and looked away. Tension kept her shoulders high and stiff. The table wobbled. Giorgina took a deep breath, meant to steady herself, but it only pulled her veil back into her throat, choking her.

“It’s all right, Sheikh Nasef,” said Labiba amiably. She smiled at Wael and his wife. “I understand your hesitation, my lady, my lord.” She inclined her head. “But if you’ll let me—”

But Labiba did not finish her sentence, for at that moment a stream of water came flying above their heads, dousing Labiba, soaking their papers, and splashing Giorgina, who pushed back into her chair in shock.

The teenage boys exploded in laughter as Labiba wiped water out of her eyes in confusion.

“How dare you!” shouted Nasef, his pale face shifting into a simmering red. “Weaving? In a templehouse? And for such a vile purpose—”

Etedal was already striding toward the group, her hands curled into fists. Giorgina ran out and pulled her back.

“You’ll make things worse,” said Giorgina.

“I don’t care,” snapped Etedal. But Giorgina held on to her firmly.

“I don’t condone this sort of boorish behavior, boy,” Wael said disapprovingly.

“Fine, fine.” The boy raised his hands in defeat. “It was just a joke. I take it back. I can take it back, watch this—”

He held out his hands, fingers splayed in a circle, and slowly began to bring them all together toward the center. Giorgina watched, mesmerized, as water droplets began to retract from their table, out of their soaked papers, and then, off Labiba, who winced.

“No, stop!” shouted Labiba. “You’re not doing it right!” She winced again. Etedal broke free of Giorgina and ran at the boy, who was ignoring Labiba, his focus totally on his task, his tongue poking into his cheek in concentration.

Labiba flinched. “Stop, stop!” Her shout was punctuated with a flinging hand gesture, seemingly instinctive. Out of the gesture was birthed a stream of flame, sizzling with heat, that shot forward and struck the teenage boy in the chest before he had recognized what had happened.

His shirt caught fire. He screamed, a throaty wail of terror, and stumbled back, arms flailing, his own waterweaving skills seemingly forgotten in his shock and pain.

Etedal tackled him; the pair fell to the ground in a heap. She rolled him back and forth, pulled off her shawl and used it to douse the flames, and then, for good measure, ripped off the gourd of water he had at his side and, straddling him, poured the remaining water all over his chest. Giorgina watched this with her heart hammering, and she could do nothing to control the matching tremble of the ground beneath her feet. She shut her eyes tight and grit her teeth, willing herself to calm down, to quiet her mind, before she made the quakes worse, before anyone noticed.

The boy sputtered and gasped, then sat up and shoved Etedal off him. He scrambled to his feet, kicking up sand as he stood.

In the silence, Labiba, pale and wide-eyed, said in a shaky voice, “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean that.”

“Crazy bitch,” shouted the boy, his eyes wild. He took a step forward, but Etedal shoved him back. His friends approached, scowls on their faces, fists raised, while other congregants attempted to hold some of their number back.

“Enough!” thundered Nasef.

Giorgina jumped. All eyes turned to Nasef, who stood tall in the center of the courtyard, atop the fountain. Every line on his face was contorted in fury.

“This is a templehouse of the Tetrad, not a back alley,” he hissed furiously. “I will not allow foul language or brawls or weaving. You should be utterly ashamed of yourselves.” His gaze, suddenly hawkish and harsh and years beyond his age, pinned the boys, who had the grace to look sheepish. “You will leave. Now.”

The boys shuffled away.

“And your parents will be hearing about this!” Nasef called after them. “As will the Academy!”

Wael was shaking his head. “Do you see? Always trouble, where these women are.” He took his wife and led her away.

Nasef stepped off the fountain carefully, his robes held in his hand. He glanced at Labiba, who was wringing her galabiya out. Etedal stood by her side, rubbing her back. Giorgina took two steps back and fell back into a chair; she could feel adrenaline rushing out of her limbs, leaving her bones light as feathers. The ground had stopped shaking, thank Setuket.

Nasef approached Labiba, who looked up at him hesitantly.

“Are you all right?” he asked stiffly.

“I’m fine,” said Labiba hurriedly. “Nasef, I—”

But he held up his hand. “You’re a weaver. You intentionally deceived me.”

Labiba half-shrugged. “It never came up,” she said quietly.

“I see.” Nasef glanced back at his congregants, who were gathered in groups, whispering. “You could have burned that boy alive.”

“She said she didn’t mean it,” snapped Etedal. “It was an accident, not to mention he started it.”

“I don’t weave.” Labiba raised her voice over her cousin’s. “For this exact reason. It’s dangerous. I agree with

you, Nasef, but I can’t help—”

“It’s not your fault you were never properly taught,” said Etedal furiously.

Nasef shook his head; he struggled to meet Labiba’s eyes. “I think you should go,” he said, so softly Giorgina barely heard him. “There’s been enough excitement here today. I’ll need to calm everyone.” With that he turned and walked away, herding his congregants back into the templehouse.

Labiba sank into the chair beside Giorgina. “I’m so sorry,” said Labiba, her voice a half-laugh. She rubbed at her forehead. “This was a disaster.”

Etedal leaned over the table. “There’s always a disaster. People throw things at us. They yell, they call us names. It’s all part of the deal.”

Etedal was right. From the day Giorgina had become a part of the Daughters of Izdihar, she had seen it all firsthand. She was used to the outmoded views, the prejudice, the patronizing, paternalistic attitudes, even the violence . . . but what never ceased to infuriate her was people like those teenage boys, treating them all like they were just a joke, a spectacle to be laughed at. It was one thing to be seen as dangerous, subversive—at least that meant they were being taken seriously. But how many in Alamaxa thought the Daughters of Izdihar only a cohort of silly, empty-headed girls who could do nothing, who were just wasting everyone’s time with stupidity?

Despite Nasef’s claims to the contrary, the Daughters of Izdihar followed Malak Mamdouh, and Malak was convinced that they had a chance to change Parliament’s mind in time for the signing of the new constitution, but based on what she had endured this past year, Giorgina wasn’t quite so certain of that.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...