- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

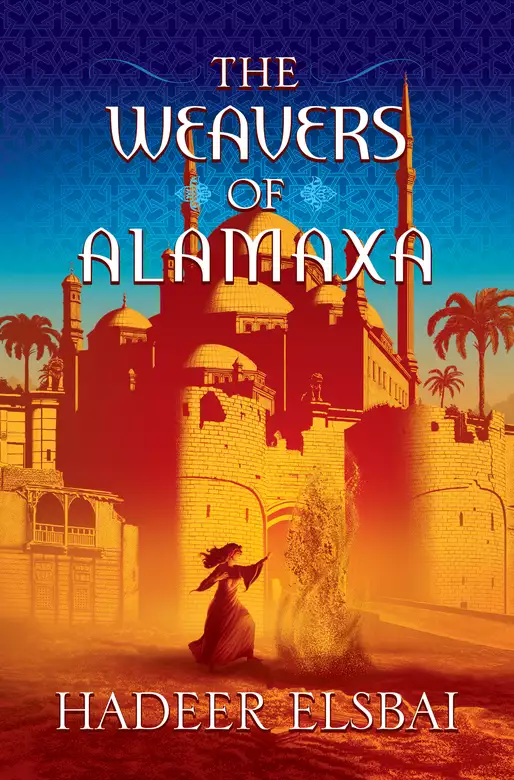

Following up on one of the most exciting fantasy debuts, The Daughters of Izdihar, Hadeer Elsbai concludes her Alamaxa Duology—inspired by Egyptian history and myth—with a tale of magic, war, betrayal, sisterhood, and love.

The world is on fire...but some women can control it.

The Daughters of Izdihar—a group of women fighting for the vote and against the patriarchal rule of Parliament—have finally made strides in having their voices heard...only to find them drowned out by the cannons of the fundamentalist Ziranis. As long as Alamaxa continues to allow for the elemental magic of the weavers—and insist on allowing an academy to teach such things—the Zirani will stop at nothing to end what they perceive is a threat to not only their way of life, but the entire world.

Two such weavers, Nehal and Giorgina, had come together despite their differences to grow both their political and weaving power. But after the attack, Nehal wakes up in a Zirani prison, and Giorgina is on the run in her besieged city. If they can reunite again, they can rally Alamaxa to fight off the encroaching Zirani threat. Yet with so much in their way—including a contingent of Zirani insurgents with their own ideas about rebellion—this will be no easy task.

And the last time a weaver fought back, the whole world was shattered.

Two incredible women are all that stands before an entire army. But they’ve fought against power before and won. This time, though, it’s no longer about rhetoric.

This time it’s about magic and blood.

Release date: March 26, 2024

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Weavers of Alamaxa

Hadeer Elsbai

Giorgina

Giorgina had always enjoyed the anonymity of the veils the Daughters of Izdihar wore, but never more so than she did now, when she was technically a fugitive.

She adjusted the black wrap to seamlessly hide her red hair, then carefully settled the thick wooden piece against her nose to ensure the veil wouldn’t flutter away in a breeze. Wearing the face veil was an old-fashioned custom, but it was not exclusive to the Daughters, so it would allow Giorgina—and Malak, who was donning her own face veil—to walk through the streets of Alamaxa unrecognized and relatively unaccosted.

Giorgina could hardly believe it had only been two days since their escape from jail, two days during which a sizable Zirani army had made itself comfortable at the city’s western border. The army had formed a large camp just outside the Alamaxa Citadel walls, with seemingly no intention of attacking.

The Alamaxa Daily was delivered to Zubaida’s brothel, where they were hiding out, but even Alamaxa’s most respectable newspaper struggled to understand what the army’s intentions were, besides intimidating Parliament. Zirana had not yet made any specific demands, and Parliament seemed willing to wait for them, as though attempting to delay the inevitable for as long as possible.

“Cowards as always,” Etedal scoffed.

Giorgina had said nothing to this. Etedal had steadily grown more irritable and volatile in the past two days. They were all anxious, but Etedal had taken to constantly fidgeting and scoffing loudly in a way that seemed to demand an answer that no one had. Thus far, Giorgina and the others had done their best to ignore this.

Giorgina also suspected the stagnancy of the past two days had given Etedal little to do but think of Labiba. With that, Giorgina could easily sympathize. When she struggled to sleep at night, she alternated between luridly colorful visions of Labiba’s bloodied galabiya and Naji Ouazzani’s crushed body.

Yet Giorgina did not think she agreed entirely with Etedal’s assessment of Parliament’s character at this

moment. She had little faith in the senators generally, but at this point it seemed waiting was far more prudent than blindly reacting, since they knew nothing for certain.

More frustrating for Giorgina personally was not knowing precisely how intent the police were on finding her and Malak. Mention of their escape had not seeped into the Alamaxa Daily as Giorgina had expected it to. Whether this was because the police did not want to reveal their incompetence or because other matters had taken precedence, Giorgina was not certain. Still, she doubted the police had simply forgotten. Attia Marwan, who had gleefully arrested them himself, was sure to remember them and note their absence. More likely their escape had been reported to Parliament. But there was nothing she could do about that now.

Bahira, who had settled back into the brothel with unease and worried she might draw the police after her escape from prison, now scowled at Malak and Giorgina as they adjusted their veils.

“You shouldn’t be going out at all,” Bahira insisted. “It’s too dangerous.”

Malak settled her veil down over her face so that only her eyes were showing. “No one will recognize us.”

“But there’s no point to this,” Bahira argued. “You just want to see her.”

Malak raised a single eyebrow, and Bahira looked away, a slight blush on her cheeks.

“Nehal and Nico have resources,” said Malak. “We can’t stay here forever, after all.”

“It’s been two days,” countered Bahira. “There’s an army at our gates. Half the city’s evacuating.”

“Those with money and second homes, anyway,” Etedal said. She was lying on Bahira’s mattress, moodily picking at a loose thread.

Etedal’s words brought to mind Giorgina’s own family. Were her father and sisters still going to work? Or were they hiding in their small home, frightened of what the army might do? Could they even afford to be afraid? To evacuate? They had an aunt who lived a few miles south of Alamaxa in a small farming town, but with what resources would they undertake that journey? The train didn’t go there, even if they could afford train tickets. The journey on foot would be perilous and would take weeks. No, they would not flee unless they were forced to. She was not certain if she wanted them to stay or go. She wanted them safe, but she also wanted them close, even if they were estranged from her.

Once they were both ready, Giorgina followed Malak downstairs to the first floor of Zubaida’s. It was too early for the brothel to be bustling with activity as it usually was in the evening, but Zubaida’s never closed, so there were still patrons being entertained in the darker corners of the parlor.

Only the barkeep glanced at Malak and Giorgina as they crossed the parlor and exited into the streets of Bulaq, one of the biggest slums in Alamaxa. It was not necessarily where Giorgina might have chosen to shelter, but given her dire circumstances, she was grateful for Bahira’s employment as Zubaida’s accountant and for the brothel madam’s willingness to shelter the four of them.

Giorgina and Malak walked down winding alleys splattered with mud and donkey droppings. A skinny stray cat tangled in Giorgina’s ankles and would have tripped her if Malak had not caught her arm. They walked hand in hand until they emerged from the depths of the slums and onto a wide main street where they could hail a mule cart to carry them the rest of the way.

Giorgina stood close to Malak, who held out her hand for a passing mule cart, which stopped to allow them on board and rushed off before Malak and Giorgina were fully seated. Giorgina’s fingers scraped against the wood of the cart, sending vibrations through her body. She gritted her teeth, forcing the discomfort down.

The cart took them as far as Ramses Street; they had to walk the rest of the way to Nico and Nehal’s house. By the time they arrived, Giorgina was sweating beneath her black garments and veil, but she would not dare to remove a single layer until she was safely indoors.

But that respite wasn’t imminent. There was a commotion at the door of Nico’s house; the familiar palanquin was at the ready. Malak gripped Giorgina’s hand to stop her walking and tugged her back. The two men

standing at the door were uniformed police officers; one was tapping his foot impatiently, arms crossed, while the other had his hands on his hips.

A moment later, another figure joined them, one Giorgina recognized with a slight lurch: Nico. She felt, upon seeing him, a wave of relief, but she tensed at how disheveled he looked. It was as though he had just been pulled out of his study; he held a travel suitcase that looked full to bursting. He spoke to the police with big gestures that conveyed irritation, but they only stared solemnly back, shaking their heads. Finally, with resignation, Nico motioned for them to go inside the house, but he did not follow them in; instead, he made for the palanquin. The police disappeared inside.

Giorgina’s heart pounded, but she tugged Malak forward. “Come on.”

“The police—”

“We’ll make it.” Giorgina was not certain where her confidence came from, but she was very aware that they needed to speak to Nico, and that need eclipsed her fear.

She and Malak rushed to the palanquin, where a young man Giorgina recognized was preparing the camel.

Giorgina lifted her face veil. “Medhat,” she said quietly.

He turned to her with a slight startle, then gave her a bemused smile. “Hello—you’re Lady Nehal’s friend, right?”

Giorgina returned his smile. “That’s right. Giorgina. I was hoping my friend and I could speak with Lord Nico?”

“Oh, sure, just give me a minute to ask.” He knocked on the palanquin door and stuck his head inside; barely a moment later, he was helping them in.

Nico pulled Giorgina in with some relief. He did not let go of her hand, even when Malak joined them and removed her own face veil. Giorgina settled beside Nico, their hands still intertwined. After the past few days, it was a comfort to be near him again. She wondered when they would again have a peaceful moment together.

Nico knocked on the roof of the palanquin, and they began to move. He turned to Giorgina.

“You’re all right,” said Nico, sighing with relief. “Thank the Tetrad. I went to try to post your bail but they said you weren’t in your cell and I didn’t know what—”

“I escaped,” interrupted Giorgina.

“She helped all of us escape.” Malak was watching them with something like fondness. “She’s gotten far better at controlling her earthweaving.”

Giorgina swelled with pride, but it mingled with guilt at the memory of the death of Naji Ouazzani and the knowledge that she had inadvertently caused the current siege of the city. She glanced down at the hand in her lap, loathing the mixture of triumph and shame she felt. Nico squeezed her other hand without a word.

“Now, where is Nehal?” asked Malak.

Nico grimaced. “Oh no. I was hoping you knew.”

Malak

went very still for a long moment, until she blinked. “What does that mean?”

Nico ran a hand through his hair, which he did often when he was frustrated; the blond curls became even more disheveled. “She vanished the night of your arrest. She’d been speaking with one of our guests on the roof, and then the bells rang, and I went to find her, but she was nowhere to be found. Then I heard you’d escaped, and I thought maybe she’d had something to do with that.”

“We haven’t seen Nehal at all,” said Giorgina slowly. “I don’t understand. Where is she?”

“I have no idea! The police seem to think she’s become a fugitive, and since she’s out on bail, they’ve seized the house.” Nico grimaced. “My father summoned me home, ranting about Nehal as always.”

“Nehal wouldn’t run away,” said Malak. “That’s not in her nature.”

“Wouldn’t she?” argued Nico. “If we’re talking about her nature, I’m sure the last thing she wants is to risk being trapped in prison for any length of time, so is it so unlikely she tried to find freedom?”

“Were her belongings missing?” Malak asked.

Nico hesitated for a moment, as though giving this question the utmost consideration. “Well, no, her things are still in her room.”

Malak waved a hand, as though this explained it all.

And to Giorgina, it did. While it was not an entirely outlandish thought that Nehal might flee, the logistics of it made little sense. Why would she run so suddenly, without any belongings, and without letting Nico or Malak know? Why would she not avail herself of her parents’ resources? Surely if she intended to skip bail she would have asked for their help to return to her hometown of Ramina and vanish there.

So no, Georgina didn’t think Nehal had run away. But that meant she hadn’t left of her own accord.

“She wouldn’t just leave,” said Malak, coming to the same conclusion as Giorgina had. “She’s in trouble. She must be.”

Frowning, Nico looked out the tiny window of the palanquin, though he must not have been able to see much of the outside through the intricate lattice design. “If she is, I have no idea where to even begin looking for her.” He looked at Malak. “Do you?”

Malak’s lips pursed infinitesimally. “I don’t.”

“And what about the massive army camped at our gates—you know people are starting to evacuate?” He shook his head. “It’s all madness. I’m tempted to evacuate myself, and . . . Giorgina, you should come with me,” he blurted. “We can leave together, leave all this behind.” He looked at her imploringly.

Giorgina was startled by her unwillingness to flee Alamaxa. This was her home, after all, and her family was still here. She told Nico as much.

“Bring your family!” Nico waved a hand in the air, as though bringing her entire family along with them or convincing them to come was no matter at all. “I’ll work it out, somehow.”

But it was not just her family. Giorgina had started something,

however inadvertently, and was it not her responsibility to finish it? She couldn’t simply leave the chaos behind and hope someone else would take care of it. That had never been in her nature, not since the day she’d decided to join the Daughters of Izdihar.

Before she could tell Nico this, Malak said quietly, “The police will likely be overseeing any evacuations out of the city.” She exchanged a quick look with Giorgina. “Giorgina’s name and image could be on some sort of fugitive list, even if they haven’t advertised it. She could be arrested trying to escape. It’s safer to stay put for now.”

Nico looked stunned, but recovered quickly. “Fine. Then I’m not leaving. Where are you both staying? Are you safe? I could—”

“We’re all right, Nico,” Giorgina interrupted gently. “We’re staying with Bahira, at a place called Zubaida’s, in Bulaq.”

“Oh, in . . . Bulaq? I—all right.” He looked somewhat flustered, as though he had far more to say about their residing in Bulaq, but instead he just reached into his pocket. “Then take this. Both of you.” He pulled out a wad of money and split it in two.

Somewhat to Giorgina’s surprise, Malak accepted the money with absolutely no hesitation. When Giorgina wavered, Malak gave her a wryly amused look. “We’re in rather dire straits, and pride does very little for the desperate.”

At that, Giorgina took Nico’s offering with a nod of thanks, though she could not quite meet his eyes.

“I just want to do something to help,” Nico said. “Anything you need, whatever I can do.”

“I’ll certainly let you know,” said Malak. “At this point, though, I’m not entirely sure what there is to be done.” She sat back, brow vaguely furrowed, gaze directed at nowhere in particular. “I’m convinced Nehal’s in trouble, but I have no idea what kind.” She refocused her gaze on Nico. “What do her parents think?”

Nico shrugged again. “They’ve been asking around, and they spoke to the police commander, but no one seems to know a thing.”

Malak shook her head. “Where could she possibly be?”

Nehal

Nehal felt herself going in and out of consciousness. She opened her eyes, stirred, and felt the fog in her mind begin to clear, but almost immediately she went under again, her limbs too heavy to move, as if a wave had overtaken her.

She had no sense of time or place. When she opened her eyes, the world was as dark as it was when she had them closed, so she kept them shut. She was tired, so tired, and the strength it would take to sit up felt monumental.

Then, minutes or hours later, she felt herself coming awake and staying awake. It took effort to peel her lips apart; her mouth was so dry her teeth stuck together. With great effort, she lifted her arms and pushed herself up, inhaling sharply. Nausea and dizziness overtook her immediately, and she shut her eyes until she felt steady enough to open them again. It was some time before the room stopped spinning.

Even thinking felt like too much effort. She struggled to pull her thoughts together, to make sense of where she was and what had happened, but she could not seem to focus long enough to do so. She settled for examining her surroundings.

She was . . . somewhere very dimly lit. A single lamp hung in the corner of what appeared to be a very small limestone room; scratchy yellow stone formed a sort of cave entrapping Nehal, with metal bars forming the fourth wall. It was so silent Nehal could hear her own rapidly fluttering heartbeat.

At the foot of the bars was a tray holding a jug of water and a bowl of medjool dates. She was so weak she could barely even feel the water. Weakly, she crawled over to the jug and, with shaking hands, lifted it to her mouth. A great deal of the stale liquid dribbled out and over her blouse, but Nehal’s parched mouth sang in relief. She set the now half-full jug down and reached for the dates, devouring all of them before she could even consider whether it was wise, whether they might be poisoned, or whether her stomach could tolerate such sweet food at the moment.

When she was finished eating, her head began to clear. She still felt weak, off-kilter, but not so much like she was going to die, which, she supposed, was a marginal improvement. Her thoughts began to coalesce, and she tried to marshal them to order, to recall what had happened to her.

The last thing she remembered was standing alone on her rooftop, and then . . .

Attia Marwan.

Somehow, he had been there, in her home, and he had injected her with something. She touched her neck where the needle had gone in and winced, surprised to find the injection site still sore. She had lost consciousness after that, and now she was here, wherever here was. Was this his revenge, then? Nehal felt a prickle of fear but buried that with rage. That son of a dog had kidnapped her!

How dare he kidnap her? Who did he think he was? Who did he think she was?

Her fury brought on a rapid heartbeat. She took deep, slow breaths to try to calm herself. She was not especially successful.

Very slowly, she dragged herself to her feet, leaning on the bars for support. She pressed her forehead against the metal in an effort to see, but the lamp provided very little light. She could barely see her own hand if she stretched it out.

“Hello?” Her voice echoed eerily in the cavern. No response came,

though Nehal had not truly expected it to. Halfheartedly, she kicked at the bars; they gave a bone-shuddering clang that made Nehal wince, but still no one came.

With a frustrated sigh, she sat back down, leaning her head against the cold, hard wall.

Where could Attia be keeping her? He could not possibly have snuck her into the police station jail cells, could he? But these walls did not look like the prison cells. Could Attia have taken her to a prison outside the city? It seemed impossible, but with the latitude he and his fellow officers were given, perhaps he could have. Nehal grimaced. Perhaps no one would have even blinked at seeing Attia carrying an unconscious woman. The thought turned her stomach, and again she marveled that Uncle Shaaban, the man who had bought her presents and lifted her onto his shoulders, was one of them. She hated that it had taken her so long to see through him.

Exhaustion overtook her once more. She closed her eyes and fell asleep.

Minutes or hours later—time meant little to Nehal down here—she heard the scrape and creak of a door being pushed open. Nehal opened her eyes with a start, at first unsure if she had dreamed the noise. But then she saw the glow of a lamp in the distance, just beyond the bars. The lamp was held high by a tall figure preceded by a much smaller one, gently illuminated in the light. The woman stopped in front of Nehal’s cell and simply looked at her. Nehal could only stare back.

She looked so . . . elaborate, like Nehal did when she was going to fancy dinner parties or to the opera, only more so. Her milk-pale face was framed by a thick black fringe of hair, much like the old-fashioned Ramsawi style, only this woman’s hair was pin-straight, and her fringe was flat and shiny. The rest of her hair was a mixture of braids and twists woven through with golden beads and pulled up to sit behind a pure gold headdress dangling with rubies.

But it was her clothing that made Nehal sit up straight. She wore a traditional Zirani caftan with billowing sleeves and a wide jeweled belt, and, even across the darkened room, Nehal could see the fine quality of the fabric.

For a moment, the two women only stared at one another, until Nehal cocked her head. “Are you the welcoming committee?”

The other woman smiled slightly, but the gesture did nothing to soften her sharp, hooded eyes. She gestured to the person holding the lamp, which was rather larger than the one in Nehal’s cell. They set it down on the ground beside the woman and disappeared into the shadows before Nehal could look at them closely.

“Are you going to say something or just stare at me?” Nehal demanded.

The woman took a step forward, the patronizing smile never leaving her face. “You do not much resemble your portrait.”

If the woman’s clothing had not been revealing enough of her origins, her Zirani dialect would have betrayed her.

Nehal crossed her legs and rested her elbows on her knees. “And why, precisely, have you been staring at my portrait?

The woman’s fingers, clasped together at her waist, were heavily bejeweled. “Naji Ouazzani showed it to me, when he reported to me the existence of a highborn bloodweaver.”

A chill ran through Nehal. “And who might you be?”

“Would you care to venture a guess?”

Nehal had no patience for this. “Enough with the theatrics already. Who are you? Why am I here?”

The woman’s large dark eyes were like endless voids. “I am Queen Rasida of the Zirani Kingdom.”

Nehal’s heartbeat quickened, but she only laughed as loud as she could, though even to her ears it sounded forced. “I’m important enough to warrant the queen herself coming out to Alamaxa, am I?”

“Oh, but you are not in Alamaxa anymore, Lady Nehal.” The queen of Zirana swept a hand at their surroundings, a delicate and elegant gesture. “You are in the city of Tiashar. Welcome to Zirana.”

Nehal stared at her. How long had she been unconscious? From Alamaxa’s western border, Tiashar was at least a ten-day trek across the Sahi Desert. Going by boat was far quicker, but it was still a three-day journey. How could she not remember three full days? Fear began to skitter its way down her back, but she ignored it. “Attia kept me drugged, then.”

“Yes.”

“He’s working for you.”

“In a manner of speaking.”

Nehal dug her nails into her palms. There was a riot of rage within her, and she could no longer deny her fear. She was in Zirana. As impossible as that seemed, there was too much evidence to doubt it. Which meant she was alone in a country that had made its hatred of weavers like herself very clear. She glanced at the water jug, which was still half full. It was not nearly enough to attack with, but it was better than nothing.

“All right.” Very slowly and with a grunt, Nehal got to her feet, but Rasida was much taller than she, and Nehal had to lift her chin to meet the other woman’s gaze. “You clearly sought me out specifically. Why?”

“You are very direct, Lady Nehal,” said Rasida. “I appreciate directness. I appreciate honesty. So I will be direct and honest with you in turn: you are here to prove a point. To change the fates of millions of people.”

“For someone who claims to be direct, you’re being rather vague,” said Nehal wryly. “I have no idea what any of that means.”

Queen Rasida tilted her head, considering Nehal. “You know of Zirana’s crusade against weaving, yes?”

“Oh, it’s a crusade against weaving, is it?” said Nehal. “That’s what you’re calling it now, to make it sound honorable and righteous?”

Rasida ignored her sarcasm. “It is honorable and righteous. In fact, we have struggled to find an equitable solution. My king and I have no desire to harm weavers; after all, none of you asked for your affliction. But recently, our scientists have made a brilliant discovery.” She paused, as though hoping for Nehal to ask what this discovery was, but Nehal only stared flatly back at her, and so Rasida continued, “A medicine. A simple injection, and the solution to all of our problems.”

Rasida smiled, her expression almost gentle, almost pitying, but not quite.

“What are you saying?” Nehal asked slowly.

Softly, Rasida asked, “You’ve not realized yet?” She glanced at the water jug.

“Realized what?” But even as Nehal asked, she was beginning to understand, and as her hand went up to her sore neck, the realization came crashing down upon her like a physical weight.

They would not have left her here with water if they thought she could weave.

Nehal’s stomach twisted. Heedless of Rasida, she dove for the water jug, knocking it over in her haste. The water spilled across the tray, onto the rough dirt floor. Nehal flattened her palms against it, feeling the physicality of the water, the damp.

Rasida was wrong. Nehal could feel the water, her natural awareness of her element seeking it out. The connection was weak, yes, but only because Nehal was exhausted.

Then she tried to weave.

Her muscles seized. She was overtaken by a wave of pain that seemed to come from deep within her body, as though it was rebelling against itself. She gasped and doubled over, her gorge rising. She felt water in her throat, water in her nose, but there was no water, only pain, pain so deep the room was swaying.

It took a long time for the pain to abate.

“No . . .” Her voice came out raw. On her knees, Nehal scraped her nails against the dirt. No. It was not possible. This was not possible. Weaving came from the Tetrad, surely nothing man-made could block it. She was only tired. She just needed food, rest—

But even when she had been sick, even when she had felt her worst, Nehal had always been able to weave.

Nehal shook her head, gritted her teeth. She lifted a hand, slamming it down on the tray, splashing water. She tried again to weave, as though the pain from a few moments ago had been nothing more than a fever dream, a nightmare from which Nehal could wake if she only tried hard enough.

But the pain was just as real the second time. Nehal seized with it, curled up so stiffly she could hardly breathe. She took short, slow gasps until her heartbeat slowed enough for her to take a deep breath. She looked up at Rasida, who was staring down at her sadly.

“No.” Nehal struggled to her feet, dragging herself over to the bars, flinging an arm out towards Rasida. Her guard, who had thus far remained hidden, stepped forward, wrenching out a sharp, curved sword and pointing it at Nehal’s head.

Rasida had not flinched. She placed a hand upon her

guard’s wrist and they slowly lowered their weapon, but their gaze did not leave Nehal, and it was only then that she realized the guard was a woman. Nehal blinked, confused, but she had no time to process this revelation. She looked at Rasida.

“What have you done to me?” Nehal’s voice shook with fury. “Where’s my weaving? What have you done?”

“We have given you a gift, Lady Nehal,” said Rasida calmly. “Do you not see the brilliance? Weaving is an affliction, but how can one fight an affliction that brings no suffering? The gods made your path a difficult one, but we have brought you salvation. Whenever you attempt to weave, you will feel the pain of your affliction, and so, over time, the desire to weave will erode. We have saved you, just as we will save weavers across this continent, and eventually, all the known world.”

“You . . . are fucking insane,” snarled Nehal. “Give me back my weaving. Give it back, give it back to me!” Nehal could hear herself descending into hysteria, but she did not care. She couldn’t care, not when she couldn’t weave.

Rasida only frowned. “You’re rather vulgar for a highborn lady, aren’t you?” She swept the train of her caftan forward as she turned her back on Nehal. “I’ll give you some time to calm yourself. We will discuss this further at a later time.”

“Don’t you dare leave!” Nehal shouted after the queen. “We’re not done, get back here! We’re not done! Rasida! Give me my weaving back!”

But Rasida did not even pause. As though they had not heard Nehal, Rasida and her guard left and shut the door behind them.

Nehal’s eyes stung with furious tears. She stumbled back, falling to the ground beside the overturned water jug. Drops of water fell slowly from its sharp mouth. Nehal stared at them with longing. She reached out, but her fingers trembled, and she felt, with overwhelming acuity, something she had never before experienced.

Nehal was too afraid to weave.

Giorgina

Giorgina awoke to the sound of an explosion.

She startled, nearly toppling off the floor mat she shared with Etedal, and wondered at first if the sound had come from a dream. But beside her, Etedal was stirring awake, and across the room Bahira was sitting up, looking startled. Beside her, Malak still slumbered, seeming to have slept through the noise.

“What in the name of the Tetrad was that?” Etedal demanded.

Around them the brothel seemed to come alive. Giorgina heard shouts and calls, the shuffling of hurried footsteps, and the slamming of doors.

Bahira shook Malak roughly. “Malak, wake up!”

Malak blinked her eyes open and sat up slowly. “What is it?”

“Something’s happening,” said Bahira. “There was—”

Another explosion shuddered in the distance. This one seemed louder than the one that had come before, though perhaps that was only because Giorgina was now fully conscious.

Instantly, Malak’s demeanor shifted; the sleep vanished from her expression and her eyes glowed with an alertness that seemed almost preternatural. “Has the army attacked?”

“How should we know?” said Etedal.

Malak climbed to her feet in one graceful movement that Giorgina suspected was aided by windweaving and quickly went to peer out the window. After a moment, Giorgina joined her.

All she could see was a crowd of people in the street. Many seemed to have rushed out of their homes in states of partial undress, and several were barefoot. She could see them speaking to one another and gesticulating, but she could not hear them.

“Anything?” asked Bahira.

“There is no way to know what’s happening from this room,” said Malak. Giorgina thought she heard a kernel of frustration in the statement, and she sympathized. They were safe in Zubaida’s, which was no small thing, but they were also trapped, isolated, and unaware.

“You’re right.” Etedal stood, smoothing her galabiya. “I’m going to get us something to eat.”

Giorgina startled, but before she could say anything, Bahira reacted.

“Something to eat? Have you forgotten you’re a fugitive?”

Etedal shrugged as though this were only a minor inconvenience. “We’re in Bulaq. There are no pigs here. And I’m starving.”

Bahira looked at Malak for help, but Malak only gave her a small shrug.

“Malak isn’t going to stop me,” said Etedal, wrapping herself in a black veil, “because she’s desperate to find out what’s happening.”

Malak said nothing to deny this.

Etedal was gone for over an hour. Bahira busied herself with her accounting, though it seemed inconceivable to Giorgina that the world could simply be soldiering on as usual in the midst of a possible attack, but of course it was. Malak and Giorgina had divided last night’s edition of the Alamaxa Daily and were thumbing through it, though Giorgina was having a difficult time focusing.

When Etedal returned, she carried something wrapped in greasy newspaper. She tossed it to the floor at Giorgina’s feet, then sank next to her. She started to peel it open.

“Well,” she said, crinkling the newspaper. “They’ve fired on the citadel.”

“They did what?” said Malak sharply.

To their collective frustration, Etedal slowly held up a steaming taamiya sandwich and bit into it.

“Blew a hole in the wall,” Etedal continued, her mouth full, “and destroyed the bell tower.”

Giorgina sat back, stunned. The citadel that had guarded Alamaxa for hundreds of years, with a hole in its wall? The heavy bell tower, older even than the citadel, a pile of rubble?

“How?” Malak asked. “What did they hit it with?”

Etedal shrugged. “Not sure. That’s all anybody knows.”

“Are the Zirani invading?” asked Bahira.

“Nah, not just yet. Everyone’s saying they’re still standing there, just watching.”

“So what now?” Bahira turned to Malak.

Malak looked deep in thought. It was a long moment before she answered Bahira. “They want something,” she said slowly. “This attack was a warning, a promise of capability. They must be negotiating with Parliament.” She turned away, looking out the window with the barest hint of a frown. Bahira and Giorgina waited, while Etedal continued to eat, crunching on spicy torshi with her sandwich.

“Giorgina.” Malak turned to face her. “I have an idea that might mean you would no longer be a fugitive. But it involves us negotiating with Parliament.”

Giorgina blinked. Of course she wanted to be free of the fear of arrest, but showing up on Parliament’s doorstep would surely prompt them to arrest her on sight.

Malak sensed Giorgina’s hesitation. “We wouldn’t speak to all of Parliament immediately,” she said. “First, we would see a senator friend of mine.”

“You don’t have any friends in Parliament,” said Bahira incredulously. “Anyone who sees you will have you arrested.”

“Not Hesham.”

“Hesham? Are you joking? That snake would do anything to improve his position in Parliament—”

This caught Giorgina’s attention. “Wait, do you mean Hesham Galal?” she asked. “The senator who came to speak to us at the protest?”

Malak nodded. “He’s also the minister of defense. We’ve worked together before—”

“That doesn’t mean he’s your friend,” snapped Bahira. “Especially not now!”

“—and any negotiations will have gone through him,” continued Malak without pausing.

Giorgina thought for a moment. “What’s your idea?”

“If I’m correct, Zirana is going to offer an ultimatum: surrender or be attacked with whatever strange weapon they’ve got. I’m going to suggest we use every weaver we’ve got—including you and me—as a reason Parliament shouldn’t capitulate.”

Bahira

threw up her hands. “Why would they agree to that?”

“Because,” said Malak, piercing Bahira with an intense stare, “I’m very good at what I do.”

Whether Malak was referring to her powers of weaving or oration did not matter; she was excellent at both, and everyone in the room knew it. Bahira pursed her lips.

“What do you mean, ‘suggest we use every weaver we’ve got’?” Giorgina asked slowly, her mind turning over the possible meanings.

“There will be a confrontation of some sort,” said Malak. “A battle, perhaps. You and I might end up in the thick of it. We would offer our skills in exchange for pardons.”

Etedal snorted, tossing her greasy wrapper on the floor. “So you two walk off free because you’re weavers while I’m stuck here? You all see the irony in that?”

“You have nothing to bargain with,” said Malak. “Giorgina and I do.”

Giorgina released a soft breath. If she agreed to this plan, was she consigning herself to something as outlandish as a battle? Giorgina was not built for battles, nor did she want to be. She had become better at controlling her weaving, yes, but she certainly did not have skills to offer.

“I’ll do my best to have you set aside, if it comes to it,” said Malak, as though she had intuited Giorgina’s fears. “You won’t have to fight. You’ll just be by my side.”

Giorgina considered this. Sometimes Malak spoke with such conviction that it was difficult not to trust her. But Malak had also been certain the march on Parliament would not end in violence, and that had left Labiba dead at the hands of the police. Malak was very clever, to be sure, but she was not prescient.

But still, if Giorgina could leverage her earthweaving to scrub her arrest record clean, shouldn’t she take that opportunity?

“All right,” said Giorgina. “I’ll go with you.”

Giorgina was jittery with anticipation until she and Malak began to get dressed at sunset. Bahira had remained sullen for most of the day, and Etedal, after pacing for hours, had decided to go out for a walk, despite everyone’s protestations.

“I can’t just sit here!” Etedal had erupted in frustration. “You and Giorgina get to gallivant wherever you want and I’m supposed to sit in this room like a child, waiting to be told what to do?”

No one argued with her after that, though Giorgina wished she’d had the willpower to do so. Etedal was not normally so churlish, nor so heedless of danger. But perhaps that had been Labiba reining her in. Giorgina felt a stab of grief. She wished Labiba were here with them now. Everything would have been the same, but it would have been easier, somehow.

Giorgina

and Malak wore their face veils again and descended into the fray . . . and a fray it was: Giorgina could see Alamaxans with their meager possessions piled atop their heads, children trailing them.

Where would they even go? They were leaving the only homes they had for some promise of safety, but they were going to end up on the streets, weary and hungry. Fear was compelling, and nobody knew when or where the projectiles would land next. That was enough for terror to seep into the populace. It was evident in the raised voices, the hurried and harried walks, the constant glances up at the sky.

Giorgina wasn’t immune, knowing that at any moment they could possibly be struck. All she had to assuage her was Malak’s belief that the Zirani army would not do so just yet.

Night had fallen fast, and flickering shadows filled the streets. The makeshift Parliament building was just a few streets north of Malak’s house. It was a little surreal to be in this neighborhood and not be attending a meeting for the Daughters of Izdihar. Giorgina wondered where all those women were now—probably scattered through the city, with the ones who were dependent on the Daughters’ resources likely scrabbling and desperate.

She and Malak were desperate too, weren’t they? Giorgina could hardly believe they were simply going to walk into Parliament. Malak must have had an extraordinary amount of trust in Hesham, and Malak did not trust easily, so this put Giorgina a little at ease.

“I have a plan,” Malak had said, and Giorgina believed her.

When they arrived at the squat building with its peeling paint, it was surrounded by police. The last time Giorgina had been here, she had given a speech to at least a hundred people, had looked a senator in the eye and refused to back down. She had been thrown in prison for that uncharacteristic defiance, but, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, she did not regret any of it. She wished it had all gone differently, of course, but she did not regret her actions.

“Don’t worry.” All Giorgina could see of Malak was her eyes. “Follow my lead.”

Ignoring her thumping heart and grateful for the veil that hid her face from view, she followed Malak.

“Good evening, sir,” said Malak to the police officer at the gate. “I’m here on a matter of some urgency—I need to see my cousin, Hesham Galal. Could you tell him Manar is waiting for him?”

The officer looked a bit startled. “Oh, well, Parliament is in an emergency session now, miss—”

“I know, I do,” said Malak, pitching her voice so that she sounded near tears. “But I desperately need to speak to him. If we could just be allowed to wait in his office while you alert him? Please, he’s the only person my father and I have got in the city, and I don’t know what else to do—” She cut herself off with something that sounded like a sob.

The policeman shuffled awkwardly, exchanging a glance with his compatriot, who shrugged.

“All right

,” he said. “If you’ll follow me . . .”

Despite the circumstances, Giorgina could not help but smile at Malak’s nerve. The policeman led them down a dingy hallway and stopped at one of the many identical doors lining the hall.

He motioned them inside. “If you’ll just wait in here . . .”

“Thank you so much,” said Malak.

It was astonishing to Giorgina that he had simply believed them, but she supposed most policemen were content to believe women incapable of subterfuge. They were naturally predisposed to assume they were helpless, and if it worked in their favor, Giorgina wasn’t going to protest, no matter how patronizing this attitude was.

The office was ascetic and dark, the light from a small, cloudy window doing little to brighten up the space. There was a rotting bookshelf on one side and a low desk on the other. Malak wandered, peering at anything she could see, as though gathering any possible information.

“What exactly are you going to tell him about me?” asked Giorgina while they waited.

“Only enough to convince him you’ll be an asset,” said Malak.

“But I . . .” Giorgina paused. “I know you said you’d try to keep me aside, but if you can’t, and if I weave, I’ll only cause more damage.”

Malak turned to face Giorgina, her head tilted. “Like in the courthouse?”

Giorgina blanched, her mouth parting in shock. “You—how did you—”

Malak reached for Giorgina’s hand and squeezed it. “There were very few logical possibilities, especially once you revealed yourself to be an earthweaver.”

“I’m so sorry,” said Giorgina miserably. “I know I ruined your trial. I made everything worse, but I couldn’t control it—”

“Hush, Giorgina, I know,” Malak reassured her. “Control is very difficult when you’ve had no practice. I don’t blame you, and I don’t expect anything of you.”

Giorgina had no time to respond, because the door swung open and a man walked in, the policeman at his heels. Giorgina recognized the stately senator, with his russet-brown hair and upturned eyes, immediately. He frowned at them.

“Manar?” he asked.

Malak widened her eyes and said, effusively, “Cousin!”

Hesham’s nostrils twitched. He waved the police officer off. “Leave us.”

Once he shut the door, Malak lifted her veil, and Hesham gave a deep sigh. “Why am I not surprised?”

“Nice to see you as well,” said Malak wryly.

“You’ll forgive me if I don’t offer you refreshments.” Hesham sat on the floor behind the low desk and gestured for Malak and Giorgina to do the same. “Who’s your friend?”

Malak glanced at her, and Giorgina took this as a cue to remove her own veil. She could not countenance removing it entirely, but she pushed it back a bit so tendrils of red hair slipped around her face. Hesham raised his eyebrows.

“This is Giorgina,” said Malak.

“You,” he said. “From the protest.”

Giorgina nodded.

“Hesham.” Malak drew his attention away. “What’s happening at the citadel?”

Hesham looked at her for a long moment, as though debating whether or not to reveal what he knew, but then he sighed. “Zirana attacked.”

“We do know that much. With what?”

Hesham leaned his elbows on the desk and set his chin on his clasped hands. “They’re calling them cannons. Something like trebuchets, only far more powerful, with much stronger projectiles. A rather startling new innovation.”

“But they fired on the citadel and stopped,” said Malak. “Why?”

“A warning. A threat. A demonstration.” Hesham waved his hand. “Take your pick. They’ve given us an ultimatum. Surrender and allow them to occupy Alamaxa, or they begin firing on civilian areas at random.”

Giorgina’s fingers curled on the fabric of her galabiya. Hesham’s words solidified Giorgina’s worries into imminent realities rather than abstractions.

Malak did not appear surprised. “When do they need a response?”

“Dawn.”

Giorgina drew a sharp breath. That was so soon, but of course they would not want to give the city too much time to confer and plan.

Malak nodded. “And our army is . . . ?”

“Occupied on the eastern border,” said Hesham flatly. “The Loraqi seem to have gained quite a bit of formidable weaponry in recent months.”

Malak raised an eyebrow. “What an interestingly timed coincidence.”

Hesham grimaced. “Quite.”

Giorgina looked between the pair of them. Alamaxa’s border skirmishes with Loraq had endured since before Giorgina had been born, and though they were constant, they had never before seemed truly dangerous, only an expensive nuisance. “You think Zirana is funding them?”

“The Zirani royal family is exorbitantly wealthy,” said Hesham. “And their citizens are taxed heavily. It would make sense to corner us like this.”

“But surely you’ve got some reinforcements?” said Malak, steering the conversation back to Alamaxa.

Hesham sat back, waving a hand. “We’ve called on the reserves, but they can’t do very much against these cannons, which is the point. Zirana doesn’t want to kill their soldiers in close combat, so they simply attack us from a distance with their new weapons. And I can’t risk calling back the soldiers that are holding back Loraq, not until we’re

certain we need them.”

“And you don’t think you will?” said Malak sharply. “Are you considering capitulating to their ultimatum?”

“It is . . . not an unpopular idea in Parliament,” said Hesham.

“I doubt it’s popular among the citizenry.”

“Malak—”

“I have another idea,” said Malak firmly.

Hesham’s lips curled. “Yes, I suspected that’s why you’re here. Do tell.”

Malak raised an eyebrow at Hesham’s tone, but her own remained even-tempered. “You make use of all the weavers at your disposal, rather than trying to pretend they don’t exist. Including Giorgina and me.”

Hesham’s gaze cut to Giorgina, then back to Malak. “I see.”

“In exchange for our help, you pardon us both.” Malak sat back.

“Oh?” Hesham let out a humorless laugh. “Is that right?”

“You know what a skilled weaver I am,” said Malak. She motioned to Giorgina. “Giorgina is just as skilled. We would be doing our country a service, putting our lives at risk. It’s not unheard of to grant pardons in exchange for wartime service.”

Giorgina kept her expression neutral, hoping she would not betray Malak’s lie, which she had delivered without a single beat of hesitation. Giorgina, a skilled weaver? Her hands tightened into sweaty fists.

Hesham shook his head. “Parliament will never agree—”

“You and I both know you can make them agree,” interrupted Malak. “You’re the minister of defense. You’re the prime minister’s groomed successor. He’ll listen to anything you’ve got to say, and the others will fall in line. You just need to give them a convincing argument, and then don’t give them time to debate.” She gave him a pointed look. “Considering these so-called cannons are blasting holes in our walls, it shouldn’t be too difficult to convince your colleagues to decide quickly.”

“I see you have this all planned out.” He turned to Giorgina. “And you’re in agreement with all this? You want to put yourself in that sort of danger?”

“Neither of us wants to put ourselves in danger,” answered Giorgina carefully. “But we already are in danger, along with the rest of the city. We do want to help and . . . get something in return.” She hoped this had been a satisfactory answer.

Hesham sighed. “We could pull all the weavers at the Academy . . . this is what they’ve been training for, after all, even if most of them are still green as grass,” he muttered, more to himself than to either of them.

“They’ll have me at the helm,” Malak replied.

Hesham frowned. “They won’t want to listen to you.”

“Then make them.” Malak leaned forward. “Again, don’t pretend it will be a challenge for you.”

Hesham drummed his fingers on the desk, lips pursed.

“With windweavers on the wall—with me on the wall—the

projectiles won’t make it through,” said Malak. “I guarantee it.”

After a moment, Hesham nodded slowly. “Fine. I’ll bring it to the session. Is it too much to ask that you wait here?”

Malak raised her hands. “We can wait, so long as we have your word that you’ll let us leave if things don’t go in our favor.”

Hesham got to his feet. “You would think that after all I’ve done for you, you wouldn’t need my word that I won’t throw you in jail,” he said irritably.

“But . . .”

He sighed. “But you’ve got it anyway.” ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...