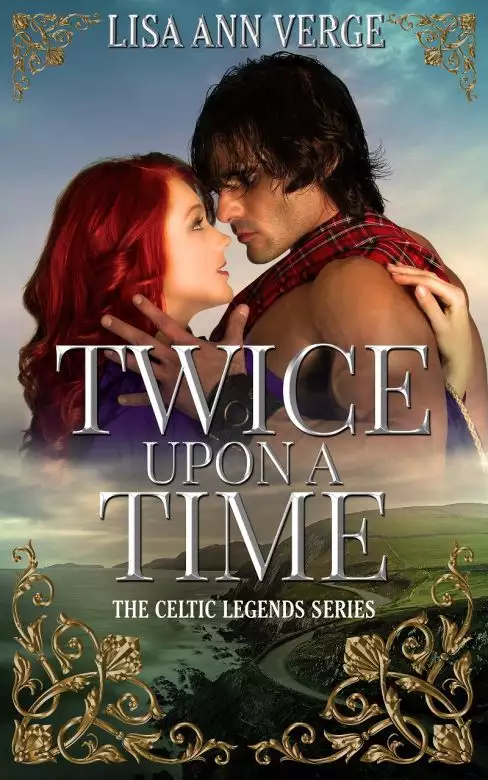

Twice Upon A Time

Prologue

France, 1223 A.D.

It was a time for dying.

Conor stood apart from the others as the ocean roared against the cliff below. Cold seeped into his tunic and drained the heat from his blood. A cluster of villagers huddled in the lee of a thatched-roofed church as the cleric muttered wind-stolen words to the wooden cross and then, ceding the battle to the coming storm, made the final sign of the cross. The villagers mimicked the motion and then rustled like a flock of ravens as they turned away.

With a heavy heart, Conor watched them disperse. Go, then, go while you can. Go to your hot stew and your loaves of thyme bread. There’s never time to mourn the dead while the business of the living continues.

His footsteps crunched across the ground. The grave diggers paused, their shovels dribbling sod. Conor pitched to one knee and clutched a handful of soil. He crumbled it between his fingers and sifted it into the pit.

Sleep easy, my old friend. May the sun shine warmly on your face.

The church bell clanged from the bell tower and echoed through the fog.

If you find her where you’re going, tell her to wait for me at the doors of Tír na nÓg one more time again.

The villagers’ gazes weighed upon his bent head. It was long past time for their suspicion and fear, he supposed. He should have known better than to linger in this tiny hamlet until all his seafaring friends lay scattered in the ground beneath him, their flesh eaten, their bones dust. But she had taught him too well. A healer could not leave a single man suffering. So he had stayed to ease the pain of the passing of the last of his companions.

Yet still he lived, still he lived—if one could call such an existence life. No warm hearth glowed for him in the village at the base of the cliff. No soft-voiced woman peered out a crack in the door, or strained her ears for his footfall. No grandchildren sprawled on the hearth to plead for stories. And now there was no longer anyone with whom to swap tales while the rain seeped through the thatched roof. No one with whom to reminisce about voyages to Venice and Rome, to Assyria and Egypt. No one with whom to share a simple meal or a simple memory.

It was a good time to die.

Conor heaved his broad-shouldered frame to its full height, not bothering to stoop and waddle as he had for so many years. Let the wind scour the ash from his hair. Let the sea mist cleanse his face and hands to uncover his unlined skin. Men saw what they expected to see. If today they finally saw him as he was, there was nothing he could do to disguise the truth. That was the way of the world.

His fog-soaked cloak snapped behind him as he turned his back to the grave and strode toward the view of the sea. The milky vapor engulfed him in an odd, welcoming warmth. He paused at the tip of the cliff and squinted toward the white-capped sea carving the shores of Marseille. Above, rain-burdened clouds jostled in the sky. Soon, he thought, the twilight between light and dark would come. Soon, the mist would be neither rain nor seawater, nor river nor well water. It would be the time between the times, as the Druids had once taught him, when the walls between the worlds grew thin.

He would choose a sea death today. He would row his fishing boat into the tempest and challenge the water’s fury. He closed his eyes, imagining the course of his coming death. The sting of liquid salt gorging his lungs. The flex and stretch of his muscles as he struggled against the inevitable suck into the ocean’s womb. The last white-hot flash of agony before the blood stopped pulsating in his temples and an unearthly warmth and darkness cradled him in silence.

Then he would see the light. He would approach it, drawn irresistibly to the glow of love and warmth and joy, like the welcoming arms of some primordial mother. He would hear the birds singing and the outline of a tree would emerge—a silver tree bathed in golden light. He would hear the bells, tinkling like fairy music. And he would know that this was Tír na nÓg, the beloved Otherworld.

He would race toward that music, race toward her, thinking this time it would be different, because hope was a tenacious plant which grew back no matter how many times it was cut. But just when he glimpsed the edge of her robes, just when he saw the tips of her fingers, outstretched for him, just when he detected the fragile scent of rainwater and honeysuckle that had always clung to her hair—that door would slam shut.

Then he would awaken, buried in the chill earth with dirt clogging his nostrils and a winding sheet stifling his movements. Still smelling her, still sensing her presence, clinging to the feeble threads of the memory until the screams of his earthly body stripped him of the last fiber and left him with a different agony. Cold. Hunger. Pain.

Wretched life.

Conor swathed his cape around his body and spun away from the cliff. He plodded through the cemetery, past the half-full grave. He no longer mourned the dead. His old friend had slipped through the door to a land of warmth and peace and pleasure. Now Conor mourned for himself, for the hell the gods had forced upon him—the loneliness, the deceit, the fear in the eyes of men. It would always be like this. He would fool himself that he could be like other men, but then another lifetime would pass, the lies would begin, his disguise grow thinner, his friends die one by one. He would try once again to leap the precipice that kept him from where he belonged, only to find himself earthbound again, forced to leave for another place, another existence, like dozens of lives before, all the same.

All but one.

A bolt of lightning cracked open the sky. Rain pelted his shoulders and sluiced down the riverbed of his face. He had relived that single life until the fabric of the memory frayed like a storm-chewed fishing net. He wished he could forget. But the memories seized him in moments of distraction. Such was the fate of a man whose heart lay in the grave.

He would never lose himself like that again, no matter where the road took him in the years ahead. For now he understood: He would have been better off if he had never known her. He would have been better off if he had never given away the full of his soul.

But it had been his first life, and he had been too young and too ignorant to guard his heart.

He had loved before he knew he was immortal.

And thus forever alone.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved