- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Bonus feature includes an original afterword by James Ellroy, titled "Hillikers," read by Stephen Hoye.

On January 15, 1947, the torture-ravished body of a beautiful young woman is found in a vacant lot. The victim makes headlines as the Black Dahlia-and so begins the greatest manhunt in California history.

Caught up in the investigation are Bucky Bleichert and Lee Blanchard. Both are obsessed with the Dahlia-driven by dark needs to know everything about her past, to capture her killer, to possess the woman even in death. Their quest will take them on a hellish journey through the underbelly of postwar Hollywood, to the core of the dead girl's twisted life, past the extremes of their own psyches-into a region of total madness.

Release date: August 12, 2025

Publisher: Vintage

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

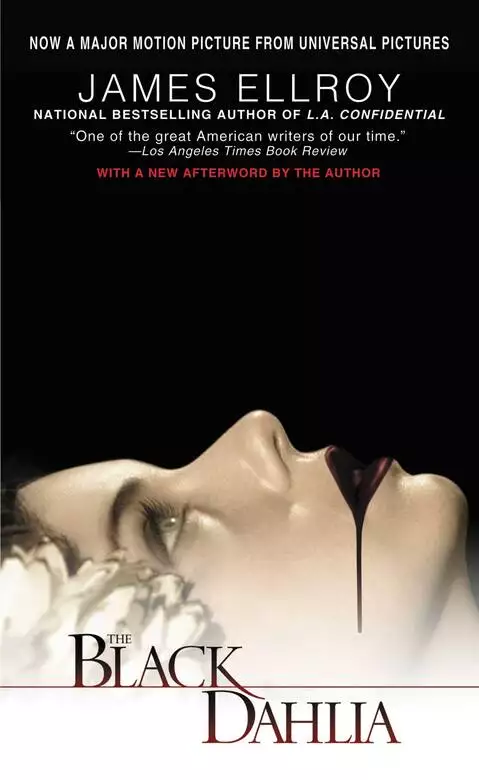

The Black Dahlia

James Ellroy

—ELMORE LEONARD

“An absolute masterpiece and Ellroy’s finest work to date… played out against a beautifully dark, moody, ’40s L.A. jazz score. The ultimate novel noir.”

—JONATHAN KELLERMAN

“If you don’t read James Ellroy’s THE BLACK DAHLIA, you will have only yourself to blame, my friend.”

—LARRY KING

“The toughest tough-guy book you’ll ever read! Big, ambitious, with passionate characters, grand obsessions, a fine sense of period and ambiance… Much more than a mystery, this is a real novel.”

—WILLIAM BAYER

“Turgid with passion, violence, and frustration… imaginative and bizarre.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A riveting 1940s noir Hollywood setting, full of period flavor and investigative detail.”

—Boston Herald

“THE BLACK DAHLIA hits you like Chinatown directed by Caryl Chessman. With it, James Ellroy surges to the forefront of contemporary American mystery fiction—Krafft-Ebing in one hand, a chainsaw in the other.”

—ANDREW VACHSS

“Ellroy has brilliantly poised the story between beauty and gross ugliness, honor and corruption, sense and loyalty, knowledge and ignorance. This is a big novel, ambitious in theme and content, and it’s the finest of its kind that I’ve read in many a year.”

—Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine

“James Ellroy has taken this unsolved murder, put his own savage spin on the story, and turned it into compelling fiction… fascinating reading, since Ellroy seemingly cannot write a dull line.”

—Hartford Courant

“THE BLACK DAHLIA meets the primary criterion of a good mystery read—you can’t put it down… Ellroy is the master of a very difficult craft.”

—San Diego Union-Tribune

“A major book.”

—Library Journal

“Fine attention to detail and dead-on sense of the period… Ellroy has established himself as one of the finest practitioners of noir fiction.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Ellroy distills the introspective style, slang, and racism of the ’40s roman noir… His characters, individuals all, are beautifully shaded, and he captures the mind-numbing detail of police work.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“Ellroy kept me glued to the chair… His ear for 1940s speech is flawless.”

—Newsweek

“A riveting, volatile, and sometimes repulsive novel… It also is raw, scary, tough, and masterful.”

—San Antonio Express-News

“A dark, compelling work of fiction… This is a tough book. It’s a good one, too.”

—San Jose Mercury News

“Ellroy’s seventh mystery and his best… The texture of his writing—dark, moody, tense—gains originality with each novel. If you want to go to hell and back, this book is for you.”

—Los Angeles Daily Breeze/News Pilot

“The novelistic equivalent of film noir.”

—Christian Science Monitor

“Ellroy’s apocalyptic visions are keenly realized, and his strong moral convictions are conveyed to the reader. This powerful and unforgettable novel should not be missed.”

—Rave Reviews

“Haunting… A book of deep friendships, conflicted love, and the brooding and merciless obsession of the characters with the Black Dahlia.”

—Los Angeles magazine

“Ellroy’s best yet… Ellroy is here to stay. Our great-grandchildren will be reading this book.”

—RICHARD LAYMAN

“A fast-moving, brutal, and enjoyable police novel… This is red-hot writing.”

—Milwaukee Journal

“Masterful… A shocker that other writers would kill to have written. This one is not to be missed; it’ll hang you out to dry.”

—HARLAN ELLISON

“Building like a symphony… a wonderful, complicated but accessible tale of ambition, insanity, passion, and deceit, with the perfect setting of booming, postwar Los Angeles.”

—Publishers Weekly

I never knew her in life. She exists for me through others, in evidence of the ways her death drove them. Working backward, seeking only facts, I reconstructed her as a sad little girl and a whore, at best a could-have-been—a tag that might equally apply to me. I wish I could have granted her an anonymous end, relegated her to a few terse words on a homicide dick’s summary report, carbon to the coroner’s office, more paperwork to take her to potter’s field. The only thing wrong with the wish is that she wouldn’t have wanted it that way. As brutal as the facts were, she would have wanted all of them known. And since I owe her a great deal and am the only one who does know the entire story, I have undertaken the writing of this memoir.

But before the Dahlia there was the partnership, and before that there was the war and military regulations and maneuvers at Central Division, reminding us that cops were also soldiers, even though we were a whole lot less popular than the ones battling the Germans and Japs. After duty every day, patrolmen were subjected to participation in air raid drills, blackout drills and fire evacuation drills that had us standing at attention on Los Angeles Street, hoping for a Messerschmitt attack to make us feel less like fools. Daywatch roll call featured alphabetical formations, and shortly after graduating the Academy in August of ’42, that was where I met Lee.

I already knew him by reputation, and had our respective records down pat: Lee Blanchard, 43-4-2 as a heavyweight, formerly a regular attraction at the Hollywood Legion Stadium; and me: Bucky Bleichert, light-heavy, 36-0-0, once ranked tenth by Ring magazine, probably because Nat Fleisher was amused by the way I taunted opponents with my big buck teeth. The statistics didn’t tell the whole story, though. Blanchard hit hard, taking six to give one, a classic headhunter; I danced and counterpunched and hooked to the liver, always keeping my guard up, afraid that catching too many head shots would ruin my looks worse than my teeth already had. Stylewise, Lee and I were like oil and water, and every time our shoulders brushed at roll call, I would wonder: who would win?

For close to a year we measured each other. We never talked boxing or police work, limiting our conversation to a few words about the weather. Physically, we looked as antithetical as two big men could: Blanchard was blond and ruddy, six feet tall and huge in the chest and shoulders, with stunted bowlegs and the beginning of a hard, distended gut; I was pale and dark-haired, all lanky muscularity at six foot three. Who would win?

I finally quit trying to predict a winner. But other cops had taken up the question, and during that first year at Central I heard dozens of opinions: Blanchard by early KO; Bleichert by decision; Blanchard stopped/stopping on cuts—everything but Bleichert by knockout.

When I was out of eye shot, I heard whispers of our non-ring stories: Lee coming on the LAPD, assured of rapid promotion for fighting private smokers attended by the high brass and their political buddies, cracking the Boulevard-Citizens bank heist back in ’39 and falling in love with one of the heisters’ girlfriends, blowing a certain transfer to the Detective Bureau when the skirt moved in with him—in violation of departmental regs on shack jobs—and begged him to quit boxing. The Blanchard rumors hit me like little feint-jabs, and I wondered how true they were. The bits of my own story felt like body blows, because they were 100 percent straight dope: Dwight Bleichert joining the Department in flight from tougher main events, threatened with expulsion from the Academy when his father’s German-American Bund membership came to light, pressured into snitching the Japanese guys he grew up with to the Alien Squad in order to secure his LAPD appointment. Not asked to fight smokers, because he wasn’t a knockout puncher.

Blanchard and Bleichert: a hero and a snitch.

Remembering Sam Murakami and Hideo Ashida manacled en route to Manzanar made it easy to simplify the two of us—at first. Then we went into action side by side, and my early notions about Lee—and myself—went blooey.

It was early June of ’43. The week before, sailors had brawled with zoot suit wearing Mexicans at the Lick Pier in Venice. Rumor had it that one of the gobs lost an eye. Skirmishing broke out inland: navy personnel from the Chavez Ravine naval base versus pachucos in Alpine and Palo Verde. Word hit the papers that the zooters were packing Nazi regalia along with their switchblades, and hundreds of in-uniform soldiers, sailors and marines descended on downtown LA, armed with two-by-fours and baseball bats. An equal number of pachucos were supposed to be forming by the Brew 102 Brewery in Boyle Heights, supplied with similar weaponry. Every Central Division patrolman was called in to duty, then issued a World War I tin hat and an oversize billy club known as a nigger knocker.

At dusk, we were driven to the battleground in personnel carriers borrowed from the army, and given one order: restore order. Our service revolvers had been taken from us at the station; the brass did not want .38’s falling into the hands of reet pleat, stuff cuff, drape shape, Argentine ducktail Mexican gangsters. When I jumped out of the carrier at Evergreen and Wabash holding only a three-pound stick with a friction-taped handle, I got ten times as frightened as I had ever been in the ring, and not because chaos was coming down from all sides.

I was terrified because the good guys were really the bad guys.

Sailors were kicking in windows all along Evergreen; marines in dress blues were systematically smashing streetlights, giving themselves more and more darkness to work in. Eschewing inter-service rivalry, soldiers and jarheads overturned cars parked in front of a bodega while navy youths in skivvies and white bell-bottoms truncheoned the shit out of an outnumbered bunch of zooters on the sidewalk next door. At the periphery of the action I could see knots of my fellow officers hobnobbing with Shore Patrol goons and MPs.

I don’t know how long I stood there, numbed, wondering what to do. Finally I looked down Wabash toward 1st Street, saw small houses, trees and no pachucos, cops or blood-hungry GIs. Before I knew what I was doing, I ran there full speed. I would have kept running until I dropped, but a high-pitched laugh issuing from a front porch stopped me dead.

I walked toward the sound. A high-pitched voice called out, “You’re the second young copper to take a powder from the commotion. I don’t blame you. Kinda hard to tell who to put the cuffs on, ain’t it?”

I stood on the porch and looked at the old man. He said, “Radio says cabdrivers been makin’ runs to the USO up in Hollywood, then bringin’ the sailor boys down here. KFI called it a naval assault, been playin’ ‘Anchors Aweigh’ every hour on the half hour. I saw some gyrenes down the street. You think this is what you call an amphibious attack?”

“I don’t know what it is, but I’m going back.”

“You ain’t the only one turned tail, you know. ’Nuther big fella came runnin’ this way pronto.”

Pops was starting to look like a wily version of my father.

“There’s some pachucos who need their order restored.”

“Think it’s that simple, laddy?”

“I’ll make it that simple.”

The old man cackled with delight. I stepped off the porch and headed back to duty, tapping the knocker against my leg. The streetlights were now all dead; it was almost impossible to distinguish zooters from GIs. Knowing that gave me an easy way out of my dilemma, and I got ready to charge. Then I heard “Bleichert!” behind me, and knew who the other runner had been.

I ran back. There was Lee Blanchard, “The Southland’s good but not great white hope,” facing down three marines in dress blues and a pachuco in a full-drape zoot suit. He had them cornered in the center walkway of a ratty bungalow court and was holding them off with parries from his nigger knocker. The jarheads were taking roundhouse swipes at him with their two-by-fours, missing as Blanchard moved sideways and back and forth on the balls of his feet. The pachuco fondled the religious medals around his neck, looking bewildered.

“Bleichert code three!”

I waded in, jabbing with my stick, the weapon hitting shiny brass buttons and campaign ribbons. I caught clumsy truncheon blows on my arms and shoulders and pressed forward so the marines would be denied swinging room. It was like being in a clinch with an octopus, and no referee or three-minute bell, and on instinct I dropped my baton, lowered my head and started winging body punches, making contact with soft gabardine midsections. Then I heard, “Bleichert step back!”

I did, and there was Lee Blanchard, the nigger knocker held high above his head. The marines, dazed, froze; the club descended: once, twice, three times, clean shots to the shoulders. When the trio was reduced to a dress blue rubble heap, Blanchard said, “To the halls of Tripoli, shitbirds,” and turned to the pachuco. “Hola, Tomas.”

I shook my head and stretched. My arms and back ached; my right knuckles throbbed. Blanchard was cuffing the zooter, and all I could think to say was, “What was that all about?”

Blanchard smiled. “Forgive my bad manners. Officer Bucky Bleichert, may I present Señor Tomas Dos Santos, the subject of an all-points fugitive warrant for manslaughter committed during the commission of a Class B Felony. Tomas snatched a purse off a hairbag on 6th and Alvarado, she keeled of a heart attack and croaked, Tomas dropped the purse, ran like hell. Left a big fat juicy set of prints on the purse, eyeball witnesses to boot.” Blanchard nudged the man. “Habla Ingles, Tomas?”

Dos Santos shook his head no; Blanchard shook his head sadly. “He’s dead meat. Manslaughter Two’s a gas chamber jolt for spics. Hepcat here’s about six weeks away from the Big Adios.”

I heard shots coming from the direction of Evergreen and Wabash. Standing on my toes, I saw flames shooting out of a row of broken windows, crackling into blue and white flak when they hit streetcar wires and phone lines. I looked down at the marines, and one of them gave me the finger. I said, “I hope those guys didn’t get your badge number.”

“Fuck them sideways if they did.”

I pointed to a clump of palm trees igniting into fireballs. “We’ll never be able to get him booked tonight. You ran down here to roust them? You thought—”

Blanchard silenced me with a playful jab that stopped just short of my badge. “I ran down here because I knew there wasn’t a goddamn thing I could do about restoring order, and if I just stood around I might have gotten killed. Sound familiar?”

I laughed. “Yeah. Then you—”

“Then I saw the shitbirds chasing hepcat, who looked suspiciously like the subject of felony warrant number four eleven dash forty-three. They cornered me here, and I saw you walking back looking to get hurt, so I thought I’d let you get hurt for a reason. Sound reasonable?”

“It worked.”

Two of the marines had managed to get to their feet, and were helping the other one up. When they started for the sidewalk three abreast, Tomas Dos Santos sent a hard right foot at the biggest of the three asses. The fat PFC it belonged to turned to face his attacker; I stepped forward. Surrendering their East LA campaign, the three hobbled out to the street, gunshots and flaming palm trees. Blanchard ruffled Dos Santos’ hair. “You cute little shit, you’re a dead man. Come on, Bleichert, let’s find a place to sit this thing out.”

• • •

We found a house with a stack of daily papers on the porch a few blocks away and broke in. There were two fifths of Cutty Sark in the kitchen cupboard, and Blanchard switched the cuffs from Dos Santos’ wrists to his ankles so he could have his hands free to booze. By the time I made ham sandwiches and highballs, the pachuco had killed half the jug and was belting “Cielito Lindo” and a Mex rendition of “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” An hour later the bottle was dead and Tomas was passed out. I lifted him onto the couch and threw a quilt over him, and Blanchard said, “He’s my ninth hard felon for 1943. He’ll be sucking gas inside of six weeks, and I’ll be working Northeast or Central Warrants inside of three years.”

His certainty rankled me. “Ixnay. You’re too young, you haven’t made sergeant, you’re shacking with a woman, you lost your high brass buddies when you quit fighting smokers and you haven’t done a plainsclothes tour. You—”

I stopped when Blanchard grinned, then walked to the living room window and looked out. “Fires over on Michigan and Soto. Pretty.”

“Pretty?”

“Yeah, pretty. You know a lot about me, Bleichert.”

“People talk about you.”

“They talk about you, too.”

“What do they say?”

“That your old man’s some sort of Nazi drool case. That you ratted off your best friend to the feds to get on the Department. That you padded your record fighting built-up middle-weights.”

The words hung in the air like a three-count indictment. “Is that it?”

Blanchard turned to face me. “No. They say you never chase cooze and they say you think you can take me.”

I took the challenge. “All those things are true.”

“Yeah? So was what you heard about me. Except I’m on the Sergeants List, I’m transferring to Highland Park Vice in August and there’s a Jewboy deputy DA who wets his pants for boxers. He’s promised me the next Warrants spot he can wangle.”

“I’m impressed.”

“Yeah? You want to hear something even more impressive?”

“Hit me.”

“My first twenty knockouts were stumblebums handpicked by my manager. My girlfriend saw you fight at the Olympic and said you’d be handsome if you got your teeth fixed, and maybe you could take me.”

I couldn’t tell if the man was looking for a brawl then and there or a friend; if he was testing me or taunting me or pumping me for information. I pointed to Tomas Dos Santos, twitching in his booze sleep. “What about the Mex?”

“We’ll take him in tomorrow morning.”

“You’ll take him in.”

“The collar’s half yours.”

“Thanks, but no thanks.”

“Okay, partner.”

“I’m not your partner.”

“Maybe someday.”

“Maybe never, Blanchard. Maybe you work Warrants and pull in repos and serve papers for the shysters downtown, maybe I put in my twenty, take my pension and get a soft job somewhere.”

“You could go on the feds. I know you’ve got pals on the Alien Squad.”

“Don’t push me on that.”

Blanchard looked out the window again. “Pretty. Make a good picture postcard. ‘Dear Mom, wish you were here at the colorful East LA race riot.’”

Tomas Dos Santos stirred, mumbling, “Inez? Inez? Qué? Inez?” Blanchard walked to a hall closet and found an old wool overcoat and tossed it on top of him. The added warmth seemed to calm him down; the mumbles died off. Blanchard said, “Cherchez la femme. Huh, Bucky?”

“What?”

“Look for the woman. Even with a snootful of juice, old Tomas can’t let Inez go. I’ll lay you ten to one that when he hits the gas chamber she’ll be right there with him.”

“Maybe he’ll cop a plea. Fifteen to life, out in twenty.”

“No. He’s a dead man. Cherchez la femme, Bucky. Remember that.”

I walked through the house looking for a place to sleep, finally settling on a downstairs bedroom with a lumpy bed way too short for my legs. Lying down, I listened to sirens and gunshots in the distance. Gradually I dozed off, and dreamed of my own few and far between women.

• • •

By the morning the riot had cooled off, leaving the sky hung with soot and the streets littered with broken liquor bottles and discarded two-by-fours and baseball bats. Blanchard called Hollenbeck Station for a black-and-white to transport his ninth hard felon of 1943 to the Hall of Justice jail, and Tomas Dos Santos wept when the patrolmen took him away from us. Blanchard and I shook hands on the sidewalk and walked separate routes downtown, him to the DA’s office to write up his report on the capture of the purse snatcher, me to Central Station and another tour of duty.

The LA City Council outlawed the wearing of the zoot suit, and Blanchard and I went back to polite conversation at roll call. And everything he stated with such rankling certainty that night in the empty house came true.

Blanchard was promoted to Sergeant and transferred to Highland Park Vice early in August, and Tomas Dos Santos went to the gas chamber a week later. Three years passed, and I continued to work a radio car beat in Central Division. Then one morning I looked at the transfer and promotion board and saw at the top of the list: Blanchard, Leland C., Sergeant; Highland Park Vice to Central Warrants, effective 9/15/46.

And, of course, we became partners. Looking back, I know that the man possessed no gift of prophecy; he simply worked to assure his own future, while I skated uncertainly toward mine. It was his flat-voiced “Cherchez la femme” that still haunts me. Because our partnership was nothing but a bungling road to the Dahlia. And in the end, she was to own the two of us completely.

The road to the partnership began without my knowing it, and it was a revival of the Blanchard-Bleichert fight brouhaha that brought me the word.

I was coming off a long tour of duty spent in a speed trap on Bunker Hill, preying on traffic violators. My ticket book was full and my brain was numb from eight hours of following my eyes across the intersection of 2nd and Beaudry. Walking through the Central muster room and a crowd of blues waiting to hear the P.M. crime sheet, I almost missed Johnny Vogel’s, “They ain’t fought in years, and Horrall outlawed smokers, so I don’t think that’s it. My dad’s thick with the Jewboy, and he says he’d try for Joe Louis if he was white.”

Then Tom Joslin elbowed me. “They’re talking about you, Bleichert.”

I looked over at Vogel, standing a few yards away, talking to another cop. “Hit me, Tommy.”

Joslin smiled. “You know Lee Blanchard?”

“The Pope know Jesus?”

“Ha! He’s working Central Warrants.”

“Tell me something I don’t know.”

“How’s this? Blanchard’s partner’s topping out his twenty. Nobody thought he’d pull the pin, but he’s gonna. The Warrants boss is this felony court DA, Ellis Loew. He got Blanchard his appointment, now he’s looking for a bright boy to take over the partner’s spot. Word is he creams for fighters and wants you. Vogel’s old man’s in the Detective Bureau. He’s simpatico with Loew and pushing for his kid to get the job. Frankly, I don’t think either of you got the qualifications. Me, on the other hand…”

I tingled, but still managed to come up with a crack to show Joslin I didn’t care. “Your teeth are too small. No good for biting in the clinches. Lots of clinches working Warrants.”

• • •

But I did care.

That night I sat on the steps outside my apartment and looked at the garage that held my heavy bag and speed bag, my scrapbook of press clippings, fight programs and publicity stills. I thought about being good but not really good, about keeping my weight down when I could have put on an extra ten pounds and fought heavyweight, about fighting tortilla-stuffed Mexican middleweights at the Eagle Rock Legion Hall where my old man went to his Bund meetings. Light heavyweight was a no-man’s-land division, and early on I pegged it as being tailor-made for me. I could dance on my toes all night at 175 pounds, I could hook accurately to the body from way outside and only a bulldozer could work in off my left jab.

But there were no light heavyweight bulldozers, because any hungry fighter pushing 175 slopped up spuds until he made heavyweight, even if he sacrificed half his speed and most of his punch. Light heavyweight was safe. Light heavyweight was guaranteed fifty-dollar purses without getting hurt. Light heavyweight was plugs in the Times from Braven Dyer, adulation from the old man and his Jew-baiting cronies and being a big cheese as long as I didn’t leave Glassell Park and Lincoln Heights. It was going as far as I could as a natural—without having to test my guts.

Then Ronnie Cordero came along.

He was a Mex middleweight out of El Monte, fast, with knockout power in both hands and a crablike defense, guard high, elbows pressed to his sides to deflect body blows. Only nineteen, he had huge bones for his weight, with the growth potential to jump him up two divisions to heavyweight and the big money. He racked up a string of fourteen straight early-round KOs at the Olympic, blitzing all the top LA middles. Still growing and anxious to jack up the quality of his opponents, Cordero issued me a challenge through the Herald sports page.

I knew that he would eat me alive. I knew that losing to a taco bender would ruin my local celebrity. I knew that running from the fight would hurt me, but fighting it would kill me. I started looking for a place to run to. The army, navy and marines looked good, then Pearl Harbor got bombed and made them look great. Then the old man had a stroke, lost his job and pension and started sucking baby food through a straw. I got a hardship deferment and joined the Los Angeles Police Department.

I saw where my thoughts were going. FBI goons were asking me if I considered myself a German or an American, and would I be willing to prove my patriotism by helping them out. I fought what was next by concentrating on my landlady’s cat stalking a bluejay across the garage roof. When he pounced, I admitted to myself how bad I wanted Johnny Vogel’s rumor to be true.

Warrants was local celebrity as a cop. Warrants was plainclothes without a coat and tie, romance and a mileage per diem on your civilian car. Warrants was going after the real bad guys and not rousting winos and wienie waggers in front of the Midnight Mission. Warrants was working in the DA’s office with one foot in the Detective Bureau, and late dinners with Mayor Bowron when he was waxing effusive and wanted to hear war stories.

Thinking about it started to hurt. I went down to the garage and hit the speed bag until my arms cramped.

• • •

Over the next few weeks I worked a radio car beat near the northern border of the division. I was breaking in a fat-mouthed rookie named Sidwell, a kid just off a three-year MP stint in the Canal Zone. He hung on my every word with the slavish tenacity of a lapdog, and was so enamored of civilian police work that he took to sticking around the station after our end of tour, bullshitting with the jailers, snapping towels at the wanted posters in the locker room, generally creating a nuisance until someone told him to go home.

He had no sense of decorum, and would talk to anybody about anything. I was one of his favorite subjects, and he passed station house scuttlebutt straight back to me.

I discounted most of the rumors: Chief Horrall was going to start up an interdivisional boxing team, and was shooting me Warrants to assure that I signed on along with Blanchard; Ellis Loew, the felony court comer, was supposed to have won a bundle betting on me before the war and was now handing me a belated reward; Horrall had rescinded his order banning smokers, and some high brass string puller wanted me happy so he could line his pockets betting on me. Those tales sounded too farfetched, although I knew boxing was somehow behind my front-runner status. What I credited was that the Warrants opening was narrowing down to either Johnny Vogel or me.

Vogel had a father working Central dicks; I was a padded 36-0-0 in the no-man’s-land division five years before. Knowing the only way to compete with nepotism was to make the weight, I punched bags, skipped meals and skipped rope until I was a nice, safe light heavyweight again. Then I waited.

I was a week at the 175-pound limit, tired of training and dreaming every night of steaks, chili burgers and coconut cream pies. My hopes for the Warrants job had waned to the point where I would have sold them down the river for pork chops at the Pacific Dining Car, and the neighbor who looked after the old man for a double sawbuck a month had called me to say that he was acting up again, taking BB potshots at the neighborhood dogs and blowing his Social Security check on girlie magazines and model airplanes. It was reaching the point where I would have to do something about him, and every toothless geezer I saw on the beat hit my eyes as a gargoyle version of Crazy Dolph Bleichert. I was watching one stagger across 3rd and Hill when I got the radio call that changed my life forever.

“11-A-23, call the station. Repeat: 11-A-23, call the station.”

Sidwell nudged me. “We got a call, Bucky.”

“Roger it.”

“The dispatcher said to call the station.”

I hung a left and parked, then pointed to the call box on the corner. “Use the gamewell. The little key next to your handcuffs.”

Sidwell obeyed, trotting back to the cruiser moments later, looking grave. “You’re supposed to report to the Chief of Detectives immediately,” he said.

My first thoughts were of the old man. I leadfooted the six blocks to City Hall and turned the black-and-white over to Sidwell, then took the elevator up to Chief Thad Green’s fourth-floor offices. A secretary admitted me to the Chief’s inner sanctum, and sitting in matched leather chairs were Lee Blanchard, more high brass than I had ever seen in one place and a spider-thin

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...