- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Christmas 1951, Los Angeles: a city where the police are as corrupt as the criminals.

Six prisoners are beaten senseless in their cells by cops crazed on alcohol. For the three L. A. P. D. detectives involved, it will expose the guilty secrets on which they have built their corrupt and violent careers.

Release date: December 2, 2025

Publisher: Vintage

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

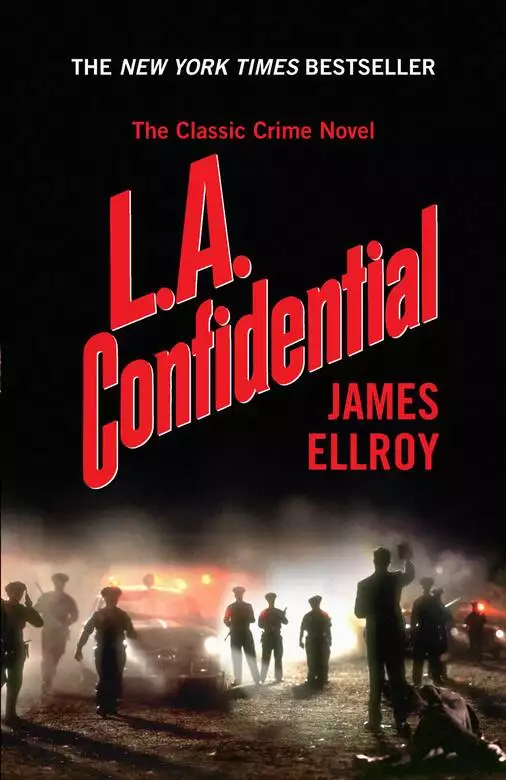

L.A. Confidential

James Ellroy

An abandoned auto court in the San Berdoo foothills; Buzz Meeks checked in with ninety-four thousand dollars, eighteen pounds of high-grade heroin, a 10-gauge pump, a .38 special, a .45 automatic and a switchblade he’d bought off a pachuco at the border—right before he spotted the car parked across the line: Mickey Cohen goons in an LAPD unmarked, Tijuana cops standing by to bootjack a piece of his goodies, dump his body in the San Ysidro River.

He’d been running a week; he’d spent fifty-six grand staying alive: cars, hideouts at four and five thousand a night—risk rates—the innkeepers knew Mickey C. was after him for heisting his dope summit and his woman, the L.A. Police wanted him for killing one of their own. The Cohen contract kiboshed an outright dope sale—nobody could move the shit for fear of reprisals; the best he could do was lay it off with Doc Englekling’s sons—Doc would freeze it, package it, sell it later and get him his percentage. Doc used to work with Mickey and had the smarts to be afraid of the prick; the brothers, charging fifteen grand, sent him to the El Serrano Motel and were setting up his escape. Tonight at dusk, two men—wetback runners—would drive him to a beanfield, shoot him to Guatemala City via white powder airlines. He’d have twenty-odd pounds of Big H working for him stateside—if he could trust Doc’s boys and they could trust the runners.

Meeks ditched his car in a pine grove, hauled his suitcase out, scoped the set-up:

The motel was horseshoe-shaped, a dozen rooms, foothills against the back of them—no rear approach possible.

The courtyard was loose gravel covered with twigs, paper debris, empty wine bottles—footsteps would crunch, tires would crack wood and glass.

There was only one access—the road he drove in on—reconnoiterers would have to trek thick timber to take a potshot.

Or they could be waiting in one of the rooms.

Meeks grabbed the 10-gauge, started kicking in doors. One, two, three, four—cobwebs, rats, bathrooms with plugged-up toilets, rotted food, magazines in Spanish—the runners probably used the place to house their spics en route to the slave farms up in Kern County. Five, six, seven, bingo on that—Mex families huddled on mattresses, scared of a white man with a gun, “There, there” to keep them pacified. The last string of rooms stood empty; Meeks got his satchel, plopped it down just inside unit 12: front/courtyard view, a mattress on box springs spilling kapok, not bad for a last American flop.

A cheesecake calendar tacked to the wall; Meeks turned to April and looked for his birthday. A Thursday—the model had bad teeth, looked good anyway, made him think of Audrey: ex-stripper, ex–Mickey inamorata; the reason he killed a cop, took down the Cohen/Dragna “H” deal. He flipped through to December, cut odds on whether he’d survive the year and got scared: gut flutters, a vein on his forehead going tap, tap, tap, making him sweat.

It got worse—the heebie-jeebies. Meeks laid his arsenal on a window ledge, stuffed his pockets with ammo: shells for the .38, spare clips for the automatic. He tucked the switchblade into his belt, covered the back window with the mattress, cracked the front window for air. A breeze cooled his sweat; he looked out at spic kids chucking a baseball.

He stuck there. Wetbacks congregated outside: pointing at the sun like they were telling time by it, hot for the truck to arrive—stoop labor for three hots and a cot. Dusk came on; the beaners started jabbering; Meeks saw two white men—one fat, one skinny—walk into the courtyard. They waved glad-hander style; the spics waved back. They didn’t look like cops or Cohen goons. Meeks stepped outside, his 10-gauge right behind him.

The men waved: big smiles, no harm meant. Meeks checked the road—a green sedan parked crossways, blocking something light blue, too shiny to be sky through fir trees. He caught light off a metallic paint job, snapped: Bakersfield, the meet with the guys who needed time to get the money. The robin’s-egg coupe that tried to broadside him a minute later.

Meeks smiled: friendly guy, no harm meant. A finger on the trigger; a make on the skinny guy: Mal Lunceford, a Hollywood Station harness bull—he used to ogle the carhops at Scrivener’s Drive-in, puff out his chest to show off his pistol medals. The fat man, closer, said, “We got that airplane waiting.”

Meeks swung the shotgun around, triggered a spread. Fat Man caught buckshot and flew, covering Lunceford—knocking him backward. The wetbacks tore helter-skelter; Meeks ran into the room, heard the back window breaking, yanked the mattress. Sitting ducks: two men, three triple-aught rounds close in.

The two blew up; glass and blood covered three more men inching along the wall. Meeks leaped, hit the ground, fired at three sets of legs pressed together; his free hand flailed, caught a revolver off a dead man’s waistband.

Shrieks from the courtyard; running feet on gravel. Meeks dropped the shotgun, stumbled to the wall. Over to the men, tasting blood—point-blank head shots.

Thumps in the room; two rifles in grabbing range. Meeks yelled, “We got him!,” heard answering whoops, saw arms and legs coming out the window. He picked up the closest piece and let fly, full automatic: trapped targets, plaster chips exploding, dry wood igniting.

Over the bodies, into the room. The front door stood open; his pistols were still on the ledge. A strange thump sounded; Meeks saw a man spread prone—aiming from behind the mattress box.

He threw himself to the floor, kicked, missed. The man got off a shot—close; Meeks grabbed his switchblade, leaped, stabbed: the neck, the face, the man screaming, shooting—wide ricochets. Meeks slit his throat, crawled over and toed the door shut, grabbed the pistols and just plain breathed.

The fire spreading: cooking up bodies, fir pines; the front door his only way out. How many more men standing trigger?

Shots.

From the courtyard: heavy rounds knocking out wall chunks. Meeks caught one in the leg; a shot grazed his back. He hit the floor, the shots kept coming, the door went down—he was smack in the crossfire.

No more shots.

Meeks tucked his guns under his chest, spread himself deadman style. Seconds dragged; four men walked in holding rifles. Whispers: “Dead meat”—“Let’s be reeel careful”—“Crazy Okie fuck.” Through the doorway, Mal Lunceford not one of them, footsteps.

Kicks in his side, hard breathing, sneers. A foot went under him. A voice said, “Fat fucker.”

Meeks jerked the foot; the foot man tripped backward. Meeks spun around shooting—close range, all hits. Four men went down; Meeks got a topsy-turvy view: the courtyard, Mal Lunceford turning tail. Then, behind him, “Hello, lad.”

Dudley Smith stepped through flames, dressed in a fire department greatcoat. Meeks saw his suitcase—ninety-four grand, dope—over by the mattress. “Dud, you came prepared.”

“Like the Boy Scouts, lad. And have you a valediction?”

Suicide: heisting a deal Dudley S. watchdogged. Meeks raised his guns; Smith shot first. Meeks died—thinking the El Serrano Motel looked just like the Alamo.

Chapter One

Bud White in an unmarked, watching the “1951” on the City Hall Christmas tree blink. The back seat was packed with liquor for the station party; he’d scrounged merchants all day, avoiding Parker’s dictate: married men had the 24th and Christmas off, all duty rosters were bachelors only, the Central detective squad was detached to round up vagrants: the chief wanted local stumblebums chilled so they wouldn’t crash Mayor Bowron’s lawn party for underprivileged kids and snarf up all the cookies. Last Christmas, some crazy nigger whipped out his wang, pissed in a pitcher of lemonade earmarked for some orphanage brats and ordered Mrs. Bowron to “Strap on, bitch.” William H. Parker’s first yuletide as chief of the Los Angeles Police Department was spent transporting the mayor’s wife to Central Receiving for sedation, and now, a year later, he was paying the price.

The back seat, booze-packed, had his spine jammed to Jell-O. Ed Exley, the assistant watch commander, was a straight arrow who might get uppity over a hundred cops juicing in the muster room. And Johnny Stompanato was twenty minutes late.

Bud turned on his two-way. A hum settled: shopliftings, a liquor store heist in Chinatown. The passenger door opened; Johnny Stompanato slid in.

Bud turned on the dash light. Stompanato said, “Holiday cheers. And where’s Stensland? I’ve got stuff for both of you.”

Bud sized him up. Mickey Cohen’s bodyguard was a month out of work—Mickey went up on a tax beef, Fed time, three to seven at McNeil Island. Johnny Stomp was back to home manicures and pressing his own pants. “It’s Sergeant Stensland. He’s rousting vags and the payoff’s the same anyway.”

“Too bad. I like Dick’s style. You know that, Wendell.”

Cute Johnny: guinea handsome, curls in a tight pompadour. Bud heard he was hung like a horse and padded his basket on top of it. “Spill what you got.”

“Dick’s better at the amenities than you, Officer White.”

“You got a hard-on for me, or you just want small talk?”

“I’ve got a hard-on for Lana Turner, you’ve got a hard-on for wife beaters. I also heard you’re a real sweetheart with the ladies and you’re not too selective as far as looks are concerned.”

Bud cracked his knuckles. “And you fuck people up for a living, and all the money Mickey gives to charity won’t make him no better than a dope pusher and a pimp. So my fucking complaints for hardnosing wife beaters don’t make me you. Capisce, shitbird?”

Stompanato smiled—nervous; Bud looked out the window. A Salvation Army Santa palmed coins from his kettle, an eye on the liquor store across the street. Stomp said, “Look, you want information and I need money. Mickey and Davey Goldman are doing time, and Mo Jahelka’s looking after things while they’re gone. Mo’s diving for scraps, and he’s got no work for me. Jack Whalen wouldn’t hire me on a bet and there was no goddamn envelope from Mickey.”

“No envelope? Mickey went up flush. I heard he got back the junk that got clouted off his deal with Jack D.”

Stompanato shook his head. “You heard wrong. Mickey got the heister, but that junk is nowhere and the guy got away with a hundred and fifty grand of Mickey’s money. So, Officer White, I need money. And if your snitch fund’s still green, I’ll get you some fucking-A collars.”

“Go legit, Johnny. Be a white man like me and Dick Stensland.”

Stomp snickered—it came off weak. “A key thief for twenty or a shoplifter who beats his wife for thirty. Go for the quick thrill, I saw the guy boosting Ohrbach’s on the way over.”

Bud took out a twenty and a ten; Stompanato grabbed them. “Ralphie Kinnard. He’s blond and fat, about forty. He’s wearing a suede loafer jacket and gray flannels. I heard he’s been beating up his wife and pimping her to cover his poker losses.”

Bud wrote it down. Stompanato said, “Yuletide cheer, Wendell.”

Bud grabbed necktie and yanked; Stomp banged his head on the dashboard.

“Happy New Year, greaseball.”

* * *

Ohrbach’s was packed—shoppers swarmed counters and garment racks. Bud elbowed up to floor 3, prime shoplifter turf: jewelry, decanter liquor.

Countertops strewn with watches; cash register lines thirty deep. Bud trawled for blond males, got sideswiped by housewives and kids. Then—a flash view—a blond guy in a suede loafer ducking into the men’s room.

Bud shoved over and in. Two geezers stood at urinals; gray flannels hit the toilet stall floor. Bud squatted, looked in—bingo on hands fondling jewelry. The oldsters zipped up and walked out; Bud rapped on the stall. “Come on, it’s St. Nick.”

The door flew open; a fist flew out. Bud caught it flush, hit a sink, tripped. Cufflinks in his face, Kinnard speedballing. Bud got up and chased.

Through the door, shoppers blocking him; Kinnard ducking out a side exit. Bud chased—over, down the fire escape. The lot was clean: no cars hauling, no Ralphie. Bud ran to his prowler, hit the two-way. “4A31 to dispatcher, requesting.”

Static, then: “Roger, 4A31.”

“Last known address. White male, first name Ralph, last name Kinnard. I guess that’s K-I-N-N-A-R-D. Move it, huh?”

The man rogered; Bud threw jabs: bam-bam-bam-bam-bam. The radio crackled: “4A31, roger your request.”

“4A31, roger.”

“Positive on Kinnard, Ralph Thomas, white male, DOB—”

“Just the goddamn address, I told you—”

The dispatcher blew a raspberry. “For your Christmas stocking, shitbird. The address is 1486 Evergreen, and I hope you—”

Bud flipped off the box, headed east to City Terrace. Up to forty, hard on the horn, Evergreen in five minutes flat. The 12, 1300 blocks whizzed by; 1400—vet’s prefabs—leaped out.

He parked, followed curb plates to 1486—a stucco job with a neon Santa sled on the roof. Lights inside; a prewar Ford in the driveway. Through a plate-glass window: Ralphie Kinnard browbeating a woman in a bathrobe.

The woman was puff-faced, thirty-fivish. She backed away from Kinnard; her robe fell open. Her breasts were bruised, her ribs lacerated.

Bud walked back for his cuffs, saw the two-way light blinking and rogered. “4A31 responding.”

“Roger, 4A31, on an APO. Two patrolmen assaulted outside a tavern at 1990 Riverside, six suspects at large. They’ve been ID’d from their license plates and other units have been alerted.”

Bud got tingles. “Bad for ours?”

“That’s a roger. Go to 5314 Avenue 53, Lincoln Heights. Apprehend Dinardo, D-I-N-A-R-D-O, Sanchez, age twenty-one, male Mexican.”

“Roger, and you send a prowler to 1486 Evergreen. White male suspect in custody. I won’t be there, but they’ll see him. Tell them I’ll write it up.”

“Book at Hollenbeck Station?”

Bud rogered, grabbed his cuffs. Back to the house and an outside circuit box—switches tapped until the lights popped off. Santa’s sled stayed lit; Bud grabbed an outlet cord and yanked. The display hit the ground: exploding reindeer.

Kinnard ran out, tripped over Rudolph. Bud cuffed his wrists, bounced his face on the pavement. Ralphie yelped and chewed gravel; Bud launched his wife beater spiel. “You’ll be out in a year and a half, and I’ll know when. I’ll find out who your parole officer is and get cozy with him, I’ll visit you and say hi. You touch her again I’m gonna know, and I’m gonna get you violated on a kiddie raper beef. You know what they do to kiddie rapers up at Quentin? Huh? The Pope a fuckin’ guinea?”

Lights went on—Kinnard’s wife was futzing with the fuse box. She said, “Can I go to my mother’s?”

Bud emptied Ralphie’s pockets—keys, a cash roll. “Take the car and get yourself fixed up.”

Kinnard spat teeth. Mrs. Ralphie grabbed the keys and peeled a ten-spot. Bud said, “Merry Christmas, huh?”

Mrs. Ralphie blew a kiss and backed the car out, wheels over blinking reindeer.

* * *

Avenue 53—Code 2 no siren. A black-and-white just beat him; two blues and Dick Stensland got out and huddled.

Bud tapped his horn; Stensland came over. “Who’s there, partner?”

Stensland pointed to a shack. “The one guy on the air, maybe more. It was maybe four spics, two white guys did our guys in. Brownell and Helenowski. Brownell’s maybe got brain damage, Helenowski maybe lost an eye.”

“Big maybes.”

Stens reeked: Listerine, gin. “You want to quibble?”

Bud got out of the car. “No quibble. How many in custody?”

“Goose. We get the first collar.”

“Then tell the blues to stay put.”

Stens shook his head. “They’re pals with Brownell. They want a piece.”

“Nix, this is ours. We get them booked, we write it up and make the party by watch change. I got three cases: Walker Black, Jim Beam and Cutty.”

“Exley’s assistant watch commander. He’s a nosebleed, and you can bet he don’t approve of on-duty imbibing.”

“Yeah, and Frieling’s the watch boss, and he’s a fucking drunk like you. So don’t worry about Exley. And I got a report to write up first–so let’s just do it.”

Stens laughed. “Aggravated assault on a woman? What’s that—six twenty-three point one in the California Penal Code? So I’m a fucking drunk and you’re a fucking do-gooder.”

“Yeah, and you’re ranking. So now?”

Stens winked; Bud walked flank—up to the porch, gun out. The shack was curtained dark; Bud caught a radio ad: Felix the Cat Chevrolet. Dick kicked the door in.

Yells, a Mex man and woman hauling. Stens aimed head high; Bud blocked his shot. Down a hallway, Bud close in, Stens wheezing, knocking over furniture. The kitchen—the spics deadended at a window.

They turned, raised their hands: a pachuco punk, a pretty girl maybe six months pregnant.

The boy kissed the wall—a pro friskee. Bud searched him: Dinardo Sanchez ID, chump change. The girl boo-hooed; sirens scree’s outside. Bud turned Sanchez around, kicked him in the balls. “For ours, Pancho. And you got off easy.”

Stens grabbed the girl. Bud said, “Go somewhere, sweetheart. Before my friend checks your green card.”

“Green card” spooked her—madre mia! Madre mia! Stens shoved her to the door; Sanchez moaned. Bud saw blues swarm the driveway. “We’ll let them take Pancho in.”

Stens caught some breath. “We’ll give him to Brownell’s pals.”

Two rookie types walked in—Bud saw his out. “Cuff him and book him. APO and resisting arrest.”

The rookies dragged Sanchez out. Stens said, “You and women. What’s next? Kids and dogs?”

Mrs. Ralphie—all bruised up for Christmas. “I’m working on it. Come on, let’s move that booze. Be nice and I’ll let you have your own bottle.”

Chapter Two

Preston Exley yanked the dropcloth. His guests oohed and ahhed; a city councilman clapped, spilled eggnog on a society matron. Ed Exley thought: this is not a typical policeman’s Christmas Eve.

He checked his watch—8:46—he had to be at the station by midnight. Preston Exley pointed to the model.

It took up half his den: an amusement park filled with papier-mâché mountains, rocket ships, Wild West towns. Cartoon creatures at the gate: Moochie Mouse, Scooter Squirrel, Danny Duck—Raymond Dieterling’s brood—featured in the Dream-a-Dream Hour and scores of cartoons.

“Ladies and gentlemen, presenting Dream-a-Dreamland. Exley Construction will build it, in Pomona, California, and the opening date will be April 1953. It will be the most sophisticated amusement park in history, a self-contained universe where children of all ages can enjoy the message of fun and goodwill that is the hallmark of Raymond Dieterling, the father of modern animation. Dream-a-Dreamland will feature all your favorite Dieterling characters, and it will be a haven for the young and young at heart.”

Ed stared at his father: fifty-seven coming off forty-five, a cop from a long line of cops holding forth in a Hancock Park mansion, politicos giving up their Christmas Eve at a snap of his fingers. The guests applauded; Preston pointed to a snow-capped mountain. “Paul’s World, ladies and gentlemen. An exact-scale replica of a mountain in the Sierra Nevada. Paul’s World will feature a thrilling toboggan ride and a ski lodge where Moochie, Scooter and Danny will perform skits for the whole family. And who is the Paul of Paul’s World? Paul was Raymond Dieterling’s son, lost tragically as a teenager in 1936, lost in an avalanche on a camping trip—lost on a mountain just like this one here. So, out of tragedy, an affirmation of innocence. And, ladies and gentlemen, every nickel out of every dollar spent at Paul’s World will go to the Children’s Polio Foundation.”

Wild applause. Preston nodded at Timmy Valburn—the actor who played Moochie Mouse on the Dream-a-Dream Hour—always nibbling cheese with his big buck teeth. Valburn nudged the man beside him; the man nudged back.

Art De Spain caught Ed’s eye; Valburn kicked off a Moochie routine. Ed steered De Spain to the hallway. “This is a hell of a surprise, Art.”

“Dieterling’s announcing it on the Dream Hour. Didn’t your dad tell you?”

“No, and I didn’t know he knew Dieterling. Did he meet him back during the Atherton case? Wasn’t Wee Willie Wennerholm one of Dieterling’s kid stars?”

De Spain smiled. “I was your dad’s lowly adjutant then, and I don’t think the two great men ever crossed paths. Preston just knows people. And by the way, did you spot the mouse man and his pal?”

Ed nodded. “Who is he?”

Laughter from the den; De Spain steered Ed to the study. “He’s Billy Dieterling, Ray’s son. He’s a cameraman on Badge of Honor, which lauds our beloved LAPD to millions of television viewers each week. Maybe Timmy spreads some cheese on his whatsis before he blows him.”

Ed laughed. “Art, you’re a pisser.”

De Spain sprawled in a chair. “Eddie, ex-cop to cop, you say words like ‘pisser’ and you sound like a college professor. And you’re not really an ‘Eddie,’ you’re an ‘Edmund.’ ”

Ed squared his glasses. “I see avuncular advice coming. Stick in Patrol, because Parker made chief that way. Administrate my way up because I have no command presence.”

“You’ve got no sense of humor. And can’t you get rid of those specs? Squint or something. Outside of Thad Green, I can’t think of one Bureau guy who wears glasses.”

“God, you miss the Department. I think that if you could give up Exley Construction and fifty thousand a year for a spot as an LAPD rookie, you would.”

De Spain lit a cigar. “Only if your dad came with me.”

“Just like that?”

“Just like that. I was a lieutenant to Preston’s inspector, and I’m still a number two man. It’d be nice to be even with him.”

“If you didn’t know lumber, Exley Construction wouldn’t exist.”

“Thanks. And get rid of those glasses.”

Ed picked up a framed photo: his brother Thomas in uniform—taken the day before he died. “If you were a rookie, I’d break you for insubordination.”

“You would, too. What did you place on the lieutenant’s exam?”

“First out of twenty-three applicants. I was the youngest applicant by eight years, with the shortest time in grade as a sergeant and the shortest amount of time on the Department.”

“And you want the Detective Bureau.”

Ed put the photo down. “Yes.”

“Then, first you have to figure a year minimum for an opening to come up, then you have to realize that it will probably be a Patrol opening, then you have to realize that a transfer to the Bureau will take years and lots of ass kissing. You’re twenty-nine now?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’ll be a lieutenant at thirty or thirty-one. Brass that young create resentment. Ed, all kidding aside. You’re not one of the guys. You’re not a strongarm type. You’re not Bureau. And Parker as Chief has set a precedent for Patrol officers to go all the way. Think about that.”

Ed said, “Art, I want to work cases. I’m connected and I won the Distinguished Service Cross, which some people might construe as strongarm. And I will have a Bureau appointment.”

De Spain brushed ash off his cummerbund. “Can we talk turkey, Sunny Jim?”

The endearment rankled. “Of course.”

“Well…you’re good, and in time you might be really good. And I don’t doubt your killer instinct for a second. But your father was ruthless and likable. And you’re not, so…”

Ed made fists. “So, Uncle Arthur? Cop who left the Department for money to cop who never would—what’s your advice?”

De Spain flinched. “So be a sycophant and suck up to the right men. Kiss William H. Parker’s ass and pray to be in the right place at the right time.”

“Like you and my father?”

“Touché, Sunny Jim.”

Ed looked at his uniform: custom blues on a hanger. Razor-creased, sergeant’s stripes, a single hashmark. De Spain said, “Gold bars soon, Eddie. And braid on your cap. And I wouldn’t jerk your chain if I didn’t care.”

“I know.”

“And you are a goddamned war hero.”

Ed changed the subject. “It’s Christmas. You’re thinking about Thomas.”

“I keep thinking I could have told him something. He didn’t even have his holster flap open.”

“A purse snatcher with a gun? He couldn’t have known.”

De Spain put out his cigar. “Thomas was a natural, and I always thought he should be telling me things. That’s why I tend to spell things out for you.”

“He’s twelve years dead and I’ll bury him as a policeman.”

“I’ll forget you said that.”

“No, remember it. Remember it when I make the Bureau. And when Father offers toasts to Thomas and Mother, don’t get maudlin. It ruins him for days.”

De Spain stood up, flushing; Preston Exley walked in with snifters and a bottle.

Ed said, “Merry Christmas, Father. And congratulations.”

Preston poured drinks. “Thank you. Exley Construction tops the Arroyo Seco Freeway job with a kingdom for a glorified rodent, and I’ll never eat another piece of cheese. A toast, gentlemen. To the eternal rest of my son Thomas and my wife Marguerite, to the three of us assembled here.”

The men drank; De Spain fixed refills. Ed offered his father’s favorite toast: “To the solving of crimes that require absolute justice.”

Three more shots downed. Ed said, “Father, I didn’t know you knew Raymond Dieterling.”

Preston smiled. “I’ve known him in a business sense for years. Art and I have kept the contract secret at Raymond’s request—he wants to announce it on that infantile television program of his.”

“Did you meet him during the Atherton case?”

“No, and of course I wasn’t in the construction business then. Arthur, do you have a toast to propose?”

De Spain poured short ones. “To a Bureau assignment for our soon-to-be lieutenant.”

Laughter, hear-hears. Preston said, “Joan Morrow was inquiring about your love life, Edmund. I think she’s smitten.”

“Do you see a debutante as a cop’s wife?”

“No, but I could picture her married to a ranking policeman.”

“Chief of Detectives?”

“No, I was thinking more along the lines of commander of the Patrol Division.”

“Father, Thomas was going to be your chief of detectives, but he’s dead. Don’t deny me my opportunity. Don’t make me live an old dream of yours.”

Preston stared at his son. “Point taken, and I commend you for speaking up. And granted, that was my original dream. But the truth is that I don’t think you have the eye for human weakness that makes a good detective.”

His brother: a math brain crazed for pretty girls. “And Thomas did?”

“Yes.”

“Father, I would have shot that purse snatcher the second he went for his pocket.”

De Spain said, “Goddammit”; Preston shushed him. “That’s all right. Edmund, a few questions before I return to my guests. One, would you be willing to plant corroborative evidence on a suspect you knew was guilty in order to ensure an indictment?”

“I’d have to—”

“Answer yes or no.”

“I…no.”

“Would you be willing to shoot hardened armed robbers in the back to offset the chance that they might utilize flaws in the legal system and go free?”

“I…”

“Yes or no, Edmund.”

“No.”

“And would you be willing to beat confessions out of suspects you knew to be guilty?”

“No.”

“Would you be willing to rig crime scene evidence to support a prosecuting attorney’s working hypothesis?”

“No.”

Preston sighed. “Then for God’s sake, stick to assignments where you won’t have to make those choices. Use the superior intelligence the good Lord gave you.”

Ed looked at his uniform. “I’ll use that intelligence as a detective.”

Preston smiled. “Detective or not, you have qualities of persistence that Thomas lacked. You’ll excel, my war hero.”

The phone rang; De Spain picked it up. Ed thought of rigged Jap trenches—and couldn’t meet Preston’s eyes. De Spain said, “It’s Lieutenant Frieling at the station. He said the jail’s almost full, and two officers were assaulted earlier in the evening. Two suspects are in custody, with four more outstanding. He said you should clock in early.”

Ed turned back to his father. Preston was down the hall, swapping jokes with Mayor Bowron in a Moochie Mouse hat.

Chapter Three

Press clippings on his corkboard: “Dope Crusader Wounded in Shootout”; “Actor Mitchum Seized in Marijuana Shack Raid.” Hush-Hush articles, framed on his desk: “Hopheads Quake When Dope Scourge Cop Walks Tall”; “Actors Agree: Badge of Honor Owes Authenticity to Hard-hitting Technical Advisor.” The Badge piece featured a photo: Sergeant Jack Vincennes with the show’s star, Brett Chase. The piece did not feature dirt from the editor’s private file: Brett Chase as a pedophile with three quashed sodomy beefs.

Jack Vincennes glanced around the Narco pen—deserted, dark—just the light in his cubicle. Ten minutes short of midnight; he’d promised Dudley Smith he’d type up an organized crime report for Intelligence Division; he’d promised Lieutenant Frieli

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...