- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

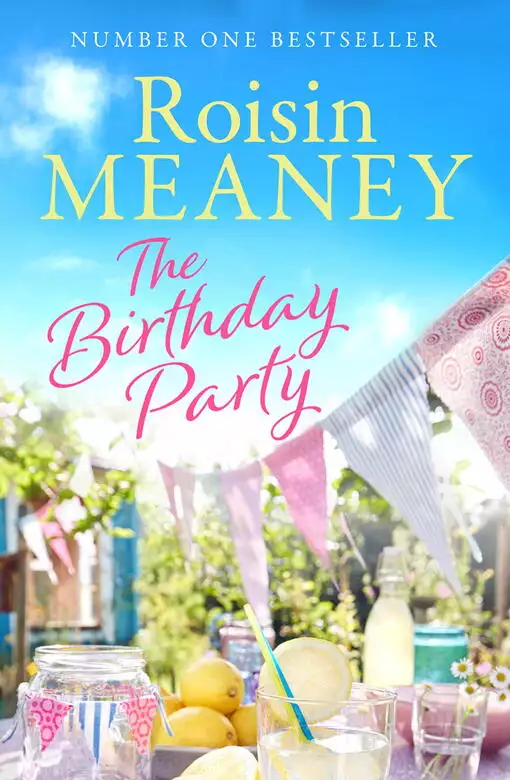

The new novel from No.1 bestselling author Roisin Meaney.

Another summer is in full swing on the island of Roone, and preparations are underway for a big birthday party at the local hotel. But beneath the air of celebration, many of the islanders have their own struggles to contend with.

Imelda, isolated by her recent heartbreak, has no memory of accepting a month-long Bed & Breakfast booking, but when a stranger turns up on her doorstep looking forward to his stay, she has little choice but to take him in.

On the other side of the world, Tilly packs her bag for a visit to Roone to spend time with her sister Laura and her long-distance boyfriend Andy, wholly unaware of the trauma that awaits her there.

Meanwhile, Laura is struggling to digest a startling confession when she finds her stepmother on her doorstep, young son in tow, having left her husband.

During six weeks of summer, love and friendships are tested – and, as the day of the party approaches, the various truths will out in unexpected ways.

(p)2019 Hachette Books Ireland

Release date: June 27, 2019

Publisher: Hachette Ireland

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Birthday Party

Roisin Meaney

A marquee set up in the grounds, because a summer garden party sounded wonderful, but everyone knew you couldn’t depend on the weather in Ireland, even in August. Lots of canapés, trays and trays of them. His chefs would be busy.

Flutes of champagne to greet everyone on arrival. Real champagne, none of your Prosecco or Cava nonsense. Wine and beer on offer too – he might steer clear of spirits – and tumblers of Mrs Bickerton’s sparkling lemonade (named after the long-departed hotel guest who had shared her recipe with Henry) for the children in attendance, and the wise older souls on the island who kept their distance from alcohol. Tea and coffee put out later, when the cake appeared.

Music, of course. He pictured a string quartet out on the lawn – or in the gazebo if the rain came. Henry was partial to a little Vivaldi in the summertime, and was casting about among his musical connections for a suitable ensemble that would fancy a night on the island.

The cake would be five tiers at least, on a scale big enough so everyone who wanted it got a taste, and ordered from the mainland so he didn’t offend any of Roone’s bakers by choosing one over another. Candles to be lit and blown out: wasn’t Henry as entitled to a wish as anyone?

No fireworks, much as he enjoyed a bit of airborne fizzle: too bright in August, the days still too long, the nights not yet cloaked in enough darkness. Fireworks, he felt, were better suited to New Year’s Eve, when he unleashed a modest number of rockets and Catherine wheels at midnight for the benefit of those who had chosen to see out the old and herald the arrival of the new at Manning’s.

A speech. He felt one should be made. Not long: the latest version had run to approximately three minutes and forty seconds when he’d tried it out before his bedroom mirror. A few words of thanks, a few amusing anecdotes pulled from his thirty-seven years at the helm of Manning’s.

A mention of his grandparents, Charles and Dolores, who had built the hotel eighty-two years ago this October – and his parents, Jerry and Tess, who’d taken it over in due course and extended it to cater for the increasing number of tourists to the island. And Victor, Henry’s older and only sibling, who’d set sail for America as a young man, in search of somewhere more adventurous than twenty-eight square miles of island set on the westernmost edge of Europe.

Victor had left Roone, but not hotels. He’d ended up with a chain of them along the American east coast, had made quite a packet before he’d jumped, aged sixty-two, from his penthouse window to escape the fire that raged below – started, it was discovered, by a carelessly wired refrigerator. No mention would be made of that sorry episode, of course. Poor Victor – dead, they’d been assured, from a heart attack before he’d hit the concrete, thirty-three floors later.

Bunting, lots of bunting. Henry had a thing for bunting. The very sight of the colourful little triangles fluttering above the lawn, any lawn, brought an answering flutter beneath his waistcoat, and made him feel instantly more festive. Even in the rain, bunting lifted the spirits – and after the recent sudden death of a much-loved island resident, spirits needed very badly to be lifted.

As to invitations, none were to be issued. Over the next few days Henry would simply put out the word that everyone was welcome, and it would pass among the islanders quicker than Fergus Masterson in his postal van. Not everyone would turn up, of course: there were those on Roone who wouldn’t be seen dead inside the hotel. Uncomfortable with a hotelier who had never produced a wife, whose interests clearly lay elsewhere – although Henry had never flaunted his status, never made any declaration, or paraded a male companion about. No matter: let them condemn him if they must. Let them stay away, and Henry would enjoy himself with guests who didn’t judge him for his preferences.

August the second he’d chosen for the party. Six days before his actual birthday, which he was planning to mark more privately, and more quietly, in Paris – but he wanted the public celebration too. He wanted the congratulations and the gifts and the toasts, surrounded by friends he’d known since boyhood, and their children and their children’s children.

Not every day a man turned seventy. Not every man batted away death for all those years. Henry intended to make the most of it, and give Roone a night it wouldn’t forget.

FOR THE PAST SIX WEEKS THERE HAD BEEN A simmering in her head. That was the only way she could put it. A slow, steady simmering, a quiet bubbling that now and again rose up and threatened to – what? Spill over and drown her. Send her screaming into the nuthouse. Cause her to do something terrible and unforgivable and irreparable.

It was a miracle she’d been able to keep afloat, to go back to work after the week off she’d been granted following Hugh’s death. It had taken everything she had not to snap at her little charges, or raise a hand and let them have it. If the parents had known how close she’d come to it once or twice, they’d have taken their children away and never allowed her within a mile of them again.

But the parents were being so gentle with her. So caring, so kind. How are you? they asked, in hushed voices. How are you coping, dear? Bringing her batches of cookies, or paper bags of apples from their trees, or pots of homemade jam. As if food, any food, could help, even if she’d been able to stomach it. As if anything could make her feel even a tiny bit less dire. She wanted to scream at them to go away, to leave her be, but of course she couldn’t do that either.

It was Hugh. It was all down to Hugh, all his fault. She couldn’t think about him, couldn’t stop thinking about him. How could he have left her? It was unconscionable that he wasn’t there any more, that she couldn’t pick up the phone and hear his voice, or meet him for one of their beach walks, or arrive at his house – his and Imelda’s house – and watch him light up with pleasure at the sight of her. That had been worth anything, the smile she’d brought to his face. Hello, minx, he’d say to her, gathering her into him with his good arm. What have you to say for yourself? Account for your movements.

It was unbearable that he would never be there again, that his chair at the top of the table was now empty, and would stay empty. She felt ragged from the loss of him, and tightly wound as a bow string, and the simmering never let up for a minute.

In the week immediately following his death, the crèche having been temporarily handed back to her predecessor Avril, Eve had spent most of her time with Imelda. Both of them too dazed to think straight, too shocked to do more than sit in silence a lot of the time, Imelda eventually getting up to reheat someone’s donated casserole that they would then push around their plates until it grew cold.

Even after she resumed work, Eve had continued to spend as much time as she could with Imelda – and every night, except for one, she’d returned to the apartment above the crèche that had been her home since January, and tried to catch even a couple of hours’ sleep.

But one night, she hadn’t. One night, only nine days after Hugh’s death, she’d sought refuge from her grief and loneliness – and now, a month later, when she’d thought things couldn’t possibly get any worse, they had. Now everything had changed again. Now, along with missing Hugh, along with wanting, every now and again, to throw something fragile against a wall, she had a new situation to grapple with, and she had no idea how she would cope. If she would cope.

‘Eve, love, you must try to eat.’

She lifted her head and looked at Imelda. If only you knew. ‘I can’t.’

‘Just take a small—’

And then it happened. Out of nowhere – only of course it wasn’t out of nowhere: it was out of the simmering of six weeks – she finally bubbled up and spilt over.

‘I can’t eat!’ she cried, shoving away her bowl of soup, causing it to shoot across the table and go flying over the edge, landing with a clatter and a reddish-brown splash on the kitchen tiles, spattering cooker and cupboard doors, and Imelda’s slippers that sat on the floor by the fridge. ‘I can’t eat – stop nagging me! You’re not my mother!’ Her voice high and shrill and not sounding at all familiar, and Imelda’s mouth dropping open, her face full of bewilderment, and Scooter appearing from under the table to lap up the spill, apparently unaware that Eve had finally taken leave of her senses, had gone over the edge as surely as the soup.

‘I can’t stand this!’ she shouted, pushing back her chair with a screech. ‘I can’t bear it! I’m going home!’

‘Eve, it’s alright, I understand you’re—’

‘You don’t understand!’ she shot back, snatching up the jacket she’d dropped in a heap on the worktop. ‘You have no idea!’ Wrenching open the back door and slamming it behind her, running from the garden to the road, blood singing in her ears, praying to God she met nobody on the way home – and for once, God listened.

In the apartment she sat with her head in her hands, trying to blot out the fact that she’d shouted at Imelda, who’d done nothing to deserve it. Still on fire inside, her breath coming short and fast, her fingertips tingling. Her phone rang, more than once: she ignored it. She sat, dry-eyed, throat hurting, wanting it all to stop. Needing it all to go away, but it wasn’t going away. It was going nowhere.

And then, as darkness crept into the room, blurring outlines, leaching colours, as her breath slowed and softened, she thought, Imelda would have left me anyway. Imelda would have left like everyone else, once word got out. So it didn’t matter that she’d blown up in the kitchen: in fact, it was probably for the best. Cut the tie, be the one to end it.

As she was undressing for bed, her phone rang again. She picked it up and saw Imelda’s name, and shut it off.

‘I’D PREFER,’ HE SAID, ‘IF YOU TOLD NOBODY ABOUT this.’

She regarded her fingers, resting on the steering wheel. There was a small blue bruise on a knuckle that she didn’t remember getting. ‘I really think you should tell Susan.’ When he didn’t respond she turned to face him. ‘Why won’t you?’

He met her gaze. ‘Because I choose not to,’ he replied, the words carrying little emotion – she never remembered him raising his voice in anger – but she could see in the tiny narrowing of his eyes the irritation the question had caused. You didn’t question him.

She looked away. She lowered her hands to rest them in her lap. Through the windscreen she watched the approach of the ferry that would take him from the island, an hour after it had dropped him here.

The surprise of seeing him on the doorstep, completely out of the blue. She’d been in the middle of cleaning up after the breakfasts – at least he hadn’t arrived in the middle of the full Irish but no tomato, and the extra toast just lightly browned, and the soft-boiled egg but make sure the white was set. At least he’d waited until all that palaver was over.

You weren’t expecting me, he’d said, which had to be the understatement of the century. He must have left Dublin at cockcrow to arrive on Roone by eleven. She wondered what he’d told Susan to explain his absence, but she knew better than to ask him that. Susan came often to Roone, but his last appearance on the island had been for Laura and Gavin’s wedding, coming on for three years ago – or was it four? They’d married in October, three months after Marian and Evie were born, which made it four years. Time flew, whether you were having fun or not.

There’s something, he’d said, I need to talk to you about – so she’d left Gav and the boys finishing off things in the house and she’d brought him out to the field, and he’d told her as they walked the perimeter what he’d come to tell her, and she’d tried to take it in, but she still hadn’t done that, not really. And then he’d asked her to drive him back to the ferry, so she’d returned to the house and got the van keys from Gav, and here they were.

‘I appreciate this,’ he said. ‘I know it’s asking a lot.’

In all her recollections he’d never asked anything of her, never looked for her help in any way before this. But this wasn’t just any old request, any old favour: this was a big one. This was about as big as it got. And to have to keep it from everyone, even Gav, even Susan, was asking a hell of a lot. She’d have to make up a tale for Gav, who’d be dying to know what had prompted the visit – and Susan could never even be told that the encounter had taken place.

She turned again to look at him, and again he met her gaze steadily. He’d never been one for looking away, she’d give him that. He met a situation head on, like he was meeting this one. He’d got older looking since their last encounter in Dublin, a year and a half earlier. The skin on his cheeks was beginning to descend, the first hint of jowls forming. The bags beneath his eyes were more pronounced, the brilliant turquoise of the irises fading, but the face was as arresting, as commanding of attention, as it had always been. Sixty-five, wasn’t he? Not old these days – and by all accounts, working as much as ever.

‘I wish …’ she began, and came to a halt. She wished so much. She wished he was different. She wished their story was different. She wished she’d held her tongue on that last encounter instead of telling him, in a fit of anger, that he would die alone. She wished they loved one another, and depended on one another, and missed each other when they were apart.

Some minuscule shift occurred in his face then, some blurring of the edges happened. ‘What do you wish?’ he asked mildly, eyes holding hers, an almost-smile on his mouth – but her courage didn’t equal his, and she shook her head.

‘So many things, I wouldn’t know where to start. We’d better get going,’ she said, reaching for the door handle.

‘Stay,’ he said, ‘there’s no need for you to come out,’ so she remained where she was, and echoed his goodbye – no embrace, never an embrace. She turned the van around while he was still walking across the pier, not thinking about the conversation they’d had in the field, because God alone knew where that might bring her. Best to put it from her, to pack it away where nobody would find it, to never dwell on it.

On the way back to Walter’s Place she thought up a story for Gav. An insurance thing, she’d say. Some official arrangement he wants to set up. To be honest, it was so boring I didn’t pay it too much attention. Some form he needs me to fill in. It wasn’t great, it wasn’t even particularly believable, but it would have to do. She hated lying, only ever did it when she knew the truth would hurt, but he’d left her with little choice.

She pulled up by the five-bar gate and got out. She left the van unlocked – this was Roone: only tourists locked their vehicles – and made her way into the field, because she felt a sudden need to talk to George.

‘What do you make of that?’ she asked him, running a hand along the rough hair of his neck. ‘Is that not the weirdest—’ And then she had to stop, because the lump in her throat was making it difficult to carry on. She lifted her face to the sky, palm resting against George’s comforting warmth, and drank in the fresh air with the taste of the sea on it until it steadied her.

‘He comes here,’ she resumed, stroking the soft ear, scratching along the length of the nose, ‘no warning, George. Not a phone call, not even a text. We could have been gone away.’ Although he’d known they wouldn’t be gone anywhere, not with the season in full swing, and the island bursting at the seams, like it always was in the summer months.

‘Why me, George? Why did he have to—’ She broke off again, blinking and swallowing, pulling more sea air into her. God, this was ridiculous. She’d have to hold it together when she went inside, or Gav would see right through her. ‘OK,’ she said then, patting the donkey’s flank. ‘OK. Thanks, George. Always good talking to you.’

He meant nothing to her. They had no bond, like a normal father and child would have. All her life he’d failed her. She’d resolved to sever ties with him that last time, sworn never to let him get to her again. And now here he was, dragging her back.

Get a grip, she told herself, crossing the field to the house. You’ve agreed to his request, nothing more to be done. It’s his problem, not yours. Let it go, let it off, don’t think about him any more.

She entered the house, setting her face to meet Gav and the kids. Becoming once more Laura the wife, Laura the mother, Laura the one who sorted things out. Laura the sister in a few weeks, when Tilly flew over from Australia to spend her third summer on Roone.

Little imagining, as she pushed open the scullery door, smile in place, that letting it go, letting it off, was going to prove completely out of the question.

HIS TIES. HIS TIES TORE HER HEART IN TWO. EVERY ONE of them drawing her back, every one of them throwing up a memory that made the loss of him a thousand times worse.

His narrow dark green tie in a fine wool. Their first dinner together in Manning’s Hotel. The salmon mousse she’d eaten in tiny morsels, terrified he’d ask her something when her mouth was full. His smile when she’d told him about the ballet classes she’d taken up the previous year, nervousness causing her to blurt it out. Kicking herself the minute she had it said, in case he thought her a fool to be doing something like that at her age. His fingers touching hers briefly when they’d both reached for the salt: the skip it had caused inside her, like a foolish smitten girl.

His navy tie with little red and grey boats stamped on it. The night he’d leant towards her as the credits were rolling after a film in Tralee – a spy thing she hadn’t been able to make an ounce of sense of – and asked her in a whisper, his breath warm on her ear, if she’d ever consider marrying him. Not three months since they’d first laid eyes on one another on Roone’s smallest pebbly beach, a day into her holiday on the island. She’d returned to Mayo less than a fortnight later, and after that the two of them had met up on Sundays only, in Tralee or Galway. Really, when you thought about it, it was no time at all to be thinking about marriage, but both of them had been certain by the time he’d asked the question. They’d reached an understanding, was how people would have put it.

His striped tie, rust and maroon and white, which had always put her in mind of a school uniform. His visit to Mayo so they could break the news together to her sister Marian and her brother-in-law Vernon. Marian’s mouth dropping open when they’d told her, for once rendered speechless. Vernon beaming like someone who’d just won the Lotto, pumping Hugh’s good arm, welcoming him to the family, telling him he was most welcome, most welcome indeed.

His wedding tie, the most heartbreaking of all. A beautiful dove grey, embossed with tiny repeated triangles in a shinier finish. His face at the top of the church, pale and tremulously smiling as she’d walked towards him on legs she couldn’t feel, hanging on tight to Vernon’s arm. Sick with nerves, but also knowing that she was entering the happiest time of her life. Wanting, despite her shakiness, to break away from Vernon and run up the aisle to him, hardly able to wait to become Mrs Hugh Fitzpatrick at the ripe old age of fifty-four. Little dreaming that before her sixtieth birthday she’d be his widow.

Was it too soon to be doing this, to be packing up his clothes? She had no template, no timetable for grief. Should she have waited longer? Probably – but she’d woken up needing to be around his things, needing to touch and sort and fold them, even if it killed her. She rolled the ties into neat rounds and secured them with straight pins. She placed them on top of the folded shirts, her heart broken clean in two with pain and loneliness and white-hot rage.

Not six years together, after waiting her whole life for him. The unfairness of it, the unbearable, unforgivable cruelty of it sent the anger raising a pulse in her temple, threatening to eat her up in its dreadful ferocity. Not even six years, when others got decades and decades, and children and grandchildren, and anniversary after anniversary after anniversary, before Death decided it was time to call a halt.

Denied his future, since losing him she’d hungered for his past. In the days that followed the funeral, when her grief had been bedding in, fierce and frightening, she’d ambushed his niece Nell, born and bred on Roone like Hugh, for what she could remember about him as a younger man, and poor Nell, full of her own loss, had battled tears as she’d reached into her memories and pulled them out.

He made a scarecrow once for some farmer who was looking for it. The head was a burst football, and he carved a bit of driftwood in the shape of the farmer’s moustache and painted it to match, and stuck it on. I remember my mother giving out to him, in case the farmer took offence, but Hugh only laughed at her.

He found a wall clock for my birthday. I would have been nine or ten. It was in the shape of a yacht, and it had an anchor for a pendulum. I thought it was the most wonderful thing I’d ever seen. It’s still around somewhere, I’m sure. I’ll have a look for it and show you.

He helped me to paint Jupiter, after Grandpa Will died, Hugh’s dad. I was seventeen, and I missed him terribly. He’d left me his little rowboat, and I got it into my head that I wanted to paint it, as a sort of tribute to him or something, I don’t know, and Hugh came with me to get the paint – I wanted something bright so we picked out yellow – and we painted it together.

I remember when his bid on Considine’s pub was accepted, and he renamed it Fitz’s and made it his own. He was so happy then, and we were all delighted for him. There was a huge session in the pub on the opening night. Nobody had planned it, but every musician on the island turned up with an instrument – and I’d swear the music never sounded better. I remember the sun coming up as I walked home with Dad.

Imelda had listened to all the silly precious recollections. She’d added them to her own pathetic few, and held them close and kept them safe. She unfolded them in the darkness of her sleepless nights and walked through his early life with him, acquainting herself with the young man she’d never known. It kept her from falling completely apart.

She closed the box that held his shirts and ties, mouth pressed tight, squeezing back the tears that wanted to fall all the time, all the time. The crying she’d done in the past seven weeks, rivers and rivers of heart-scalding tears – but there seemed to be no end to them.

Seven weeks. An eternity, an instant. Seven weeks since she’d woken and turned to him, and seen immediately that something wasn’t right. A peculiar purplish tinge to his skin, his eyes almost but not quite closed, a slackness to his features that was more than sleep, that was beyond sleep. Hugh, she’d said, thinking stroke, thinking brain bleed, not thinking worse, not yet, Hugh, wake up, reaching towards him, putting a palm to his cheek – and the horrible clammy iciness of it had made her recoil, as if he’d burnt her.

She’d risen to her knees, feeling a tumble of her insides, No, no, feeling everything in her turn to water, feeling the breath go from her, placing trembling fingers to the side of his neck, and then to his wrist, praying for a pulse, however weak, no, praying for a sign of life, no, no, no, no, no, no, gathering him up, what was left of him, pressing the coldness, the stiffness of him to her, no, no, no, howling it out, How could you? No, no, and nobody at all to hear her, with Eve moved out and Keith in Galway and God not giving a damn. While she slept beside him he’d taken his last breath and gone away from her, a month before his fifty-seventh birthday, his present of a navy sweater already bought and wrapped and sitting in the boot of her car, the only place he wouldn’t find it.

Heart, Dr Jack had said. A massive heart attack. He wouldn’t have suffered, he’d told her, and she’d clung, she was clinging, to that. Let him not have felt a thing. Let his life have come to a gentle and painless end. Let her suffer – let all the suffering be hers.

The immediate aftermath, the days following his death, she remembered only in disjointed, unrelated fragments – somewhat, she imagined, like the recollections of an Alzheimer’s patient, whose lived life could only be recalled, if at all, in haphazard, misaligned episodes.

The hands, all the hands of Roone reaching out to shake hers, not a soul on the island, young or old, who hadn’t known Hugh. Sorry for your trouble, sorry for your trouble, like a litany, like a Taizé chant, a poem learnt off by heart, the words affording some tiny solace by their very monotony. People calling her lovey and darling and pet, calling her all the names he’d called her.

The wobble in Henry Manning’s chin, his eyes swimming as he told her that Hugh’s first job had been washing up in the hotel kitchen at weekends as a schoolboy, a missing forearm no hindrance at all to him. As fast as anyone, Henry had told her, my father often said there was nobody like him to work, trembling mouth downturned in a way Imelda might have found comical, once upon a time.

The ham sandwich cut into four little squares that she’d forced herself to eat at someone’s urging. Too much butter in it, a smear of the English mustard that she hated, but she’d chewed and swallowed and washed it down with warm tea so that she’d be left alone.

The smell of wet clothes during the endless night of his wake, when people sat in relays by his coffin through the darkness, as island custom demanded. Rain pelting down outside, a fitting soundtrack it felt like.

Isolated images too. A bunch of big white and yellow daisies, tied with a green ribbon. Someone’s green quilted jacket draped over the back of a chair. Someone else’s silver drop earrings in the shape of flying birds. A biscuit sitting ignored on a saucer that had beautiful pink roses painted on it. Whose saucer? She had no idea, part of the paraphernalia of crockery and glasses that someone – Nell? – had rounded up for the wake.

The dreadful coldness of the lips she kissed as she told him goodbye, the day of the funeral. The taste of the blood she drew from her cheek, biting hard into it as the coffin lid was lowered. Trying to distract herself from the other pain, but there was no escape from it.

The feel of her sister’s arm about her waist as they stood at the open grave, her brother-in-law on her other side, propping her up between them. Nell standing ac. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...