- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

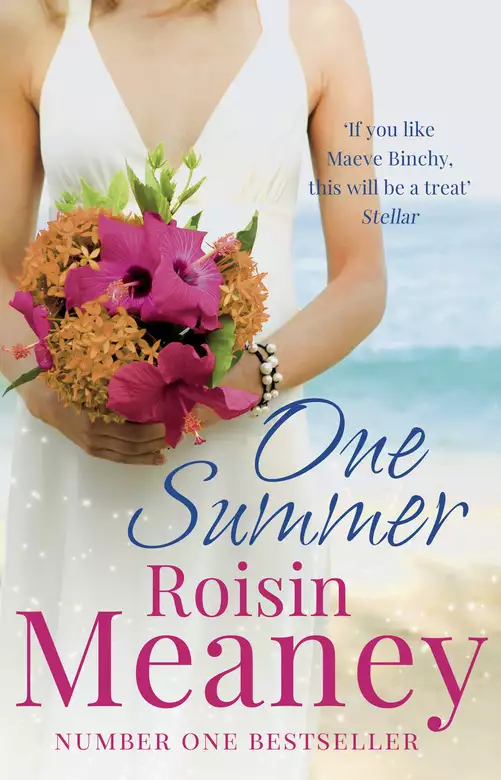

Fans of Maeve Binchy will love the number one bestseller Roisin Meaney and this heart-warming story of love, friendship and fate set on Roone, a small island off the west coast of Ireland ...

Nell Mulcahy grew up on the island so when the old stone cottage by the edge of the sea went up for sale, the decision to move back from Dublin was easy.

But when Nell decides to rent out her cottage for the summer to help raise money her forthcoming wedding to Tim, she's unprepared for what's about to happen ...

As she welcomes holiday-makers to her cottage, Nell must face some truths: about her upcoming wedding to Tim, and her friendship with his brother, James.

And, meanwhile, her father delivers some astounding news which leaves Nell, her mother and the island reeling ...

But will Nell make it down the aisle?

One thing's for sure, it's a summer on the island that nobody will ever forget.

Release date: April 5, 2012

Publisher: Hachette Ireland

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Summer

Roisin Meaney

at a small car-ferry terminal with a little slanting pier – the width, perhaps, of three vehicles – that sticks its toe into

the Atlantic Ocean. If you park in the designated waiting area and get out to stretch your legs you’ll be met, as you open

the car door, by a wash of pure fresh salt air, by the heartbreaking call of seagulls, by the intermittent slap of water against

stone.

If you stand at the edge of the pier and look out to sea you’ll catch a glimpse, on a clear day, of a landmass sitting on

the horizon, cradled between the two outermost edges of the bay on whose coastline you stand. If you drive on to the modest

ferry when it arrives – every twenty minutes, with room for eight cars – you will cover at a leisurely pace the fourteen nautical

miles that separate the mainland from the most westerly of Ireland’s islands, barely seven miles long by four wide.

And if you disembark and drive through the little village, past its two pubs and single hair salon and three cafés and scatter

of craft shops and art galleries, if you continue on past the graveyard and the creamery and the holy well, if you ignore

signs for the lighthouse and the beaches and the prehistoric remains, and keep to the main artery as it winds upwards towards

the highest of the island’s cliffs, you’ll come at last to the end of the road.

And there, two feet or more beyond the safety fence, stuck into the most outlying promontory and pointing straight out into

the Atlantic, you will see a sign that looks like any other road sign you’ll have passed along the way. The sign reads, The Statue of Liberty: 3,000 miles, and it has stood on that spot for as long as the oldest islander can remember.

And nobody – not the local county council or any of the island’s three hundred and forty-seven year-round inhabitants – has

the smallest idea where it came from.

Welcome to Roone.

‘Six weeks,’ she said, tipping powder into the drawer of the washing-machine. ‘That’s all it would take.’

Silence.

She slid the drawer shut and turned to look at him. ‘Honey? What do you think?’

Still no response. His back to her, leaning into the radiator as he looked out at the garden, or pretended to. Not much to

see in the dark.

She pressed buttons and the washing-machine growled into life and got to work. ‘Forty-two measly days, that’s all,’ she said.

‘What’s that in the grand scheme of things? Nothing.’

‘Hardly nothing.’

She shouldn’t have converted it to days: forty-two did sound like a lot. ‘OK, it’s not exactly nothing. But what’s a few weeks

when we’ve got the rest of our lives together?’

The words caused a lick of delight inside her. The rest of their lives: thousands of days ahead of them. She wiped down the

draining-board and squeezed the dishcloth into the sink, smiling at the water that dribbled down the plughole. Smiling at

everything, these days, she was. Happy as a pig in muck, she was.

They were getting married. In September he’d asked for her hand in marriage, down on bended knee on the beach, and she’d said

yes – no, she’d shouted yes, pulling him up to waltz with him into the oncoming rush of water, laughing at his protests. And

next December, on her thirty-fourth birthday, they were going to bind themselves to each other till death them did part.

Years and years ahead of them, barring any nasty accidents or diseases. Assuming that neither of them crossed paths with a

crazed gunman or boarded a plane that was destined to have an encounter with a tall building.

‘Promise me we’ll always travel together,’ she said, reaching behind to untie her apron. ‘In planes, I mean.’ If she was going

to be flown into a skyscraper she wanted him right there next to her, squeezing her hand all the way to eternity.

He turned. ‘What?’

She often puzzled him, poor love. She dropped the apron on the draining-board and regarded him happily. ‘Oh, nothing,’ she

said. ‘Just thinking out loud.’

Look at those cat-green eyes, that adorably full bottom lip, the silky muddy-blond hair that just begged to be tousled. Look

how lucky she was, the luckiest girl on Roone.

They were different, oh, just about as different as two people could be. He was the cautious one, always planning for the

future; she liked diving into days without a plan.

Her wardrobe was full of things that didn’t go with any other things. He shopped for clothes once a year, with a list; he

was lost without a list. She regularly ran out of phone credit. He had new toiletries waiting when the old ones were still

a quarter full.

He frowned at her; she laughed at him. He didn’t get the way her mind skipped ahead of itself sometimes, darting from one

idea into another without waiting for anyone to catch up. He was more the one-logical-step-at-a-time kind of person – which

meant, of course, that he was ideal for her. She needed somebody logical in her life, to grab her when she veered too far

off course. They were the perfect match, polar opposites irresistibly drawn towards each other.

Tim, of course, had been scandalised when Nell told him she’d bought the first house she’d looked at, three years earlier

at the ripe old age of thirty. It had belonged to Seánín Fionn, seventh son of a seventh son, and recently deceased after

eighty-seven years of healing that no doctor could achieve, or explain.

The house was in need of much redecorating – Seánín Fionn’s interests had lain beyond wallpapering and painting – but as soon

as Nell had stepped through the peeling front door she had experienced the strangest rush of well-being, as if she was doing

something exactly right. ‘Oh –’ she’d said, causing the estate agent, who’d come all the way from Dingle, to ask if anything was wrong.

‘No,’ she’d told him, her hand pressed to her happily fluttering heart, ‘nothing’s wrong, nothing at all.’

And if she’d had any doubts after that that this was the house for her, they’d been banished by the black and white dog that

was still hanging around the property, looking hungry and sad, it seemed to Nell.

‘Is anyone feeding him?’ she’d asked the estate agent. ‘Are you trying to find him a home?’

The young man – whose name, he’d told her, was Brendan, and whose stiff new shirt collar was chafing his neck – was clearly

doing nothing of the sort. ‘I’ve had no instruction about the dog,’ he’d said, ushering Nell through to the little sitting

room, pushing a bent metal coat hanger out of the way with the shiny toe of his black shoe. ‘He’s not really our concern.’

Not their concern, shivering outside the window, looking in at him and Nell with an expression that said, ‘Don’t you care?

Doesn’t anyone care about me any more?’

On the spot she’d made an offer. She’d gone straight from the house to the supermarket for a plastic pouch of dog food, and

brought it back to him. She’d torn it open and placed it on the lawn, and he’d gobbled its contents, licked it clean and looked

hopefully up at her, tail wagging. A week later she’d signed the contract. Every day in between she’d returned to the garden

with her dinner leftovers, and rashers stolen from her mother’s fridge.

A month later, having kept up the daily feeds, she’d got the keys and moved in with a stack of books, a microwave and a camp

bed. Her new neighbour, whom she already knew, of course, this being Roone – and who’d also, she discovered, been on dog-feeding

duty – had told her that the animal was called John Silver, and Nell had been happy to leave that unchanged. It was perfect

for him, with the black patch around his right eye. They’d taken to each other wonderfully.

And from the start, it was as if the house had accepted Nell too. She’d lain in her camp bed at night, deliciously drowsy,

smelling the fresh paint and wood varnish that no amount of open windows would banish – it would leave when it was good and

ready – and she’d felt safe and cherished, and truly at home. Maybe it was Seánín Fionn, sending gentle good wishes from whatever dimension he’d travelled to.

‘I can’t believe you bought the first house you saw,’ Tim had said. ‘You didn’t even look at any others?’

‘I loved it as soon as I walked in,’ Nell had told him, ‘and it loved me back. And this is Roone, remember; I could have been

waiting ages for another to come up. And, anyway, this house had a dog going with it, and he needed me.’

Tim had opened his mouth again, no doubt to put forward another argument. Nell had felt obliged to put an end to it by kissing

him.

And now here she was, trying to plan ahead for once, like he was always telling her to do. You’d think he’d be delighted,

but he wasn’t showing an ounce of enthusiasm. Clearly, more work was needed, which didn’t bother Nell at all. She had a history

of getting her own way with him.

She brushed a scattering of crumbs from the tablecloth into her hand. ‘Houses around here are getting four hundred euro a

week in July and August,’ she said. ‘Two bedrooms, just like this one. In six weeks we’d make well over two thousand euro.’

‘We don’t need two thousand euro,’ Tim said. ‘You know I’ll pay for the wedding, I’ve said I will. You know I can well afford

it.’

‘And you know I’m not going to let you,’ she replied, ‘because I’m stubborn and independent, and all those other things you

love about me.’

‘I don’t love everything about you.’

She adored the huskiness a head cold gave to his voice. She walked over to him and slid an arm around his waist. ‘Oh, yes,’

she said softly, standing on tiptoe to kiss his chin, ‘you do.’

He didn’t care what kind of a wedding they had, or honeymoon. He’d get married in this kitchen if she’d let him, and book

into a B&B in Ballybunion for a week afterwards – and lovely as Ballybunion was for a summer afternoon stroll along that magnificent

beach, Nell was aiming a bit higher for her honeymoon. As high as Barbados, maybe, or Bali.

‘Come on,’ she said, burrowing into his neck. ‘Say you’ll think about it, at least.’

He sighed. ‘Honestly, Nell, I’d rather not. For one thing – well, the main thing, really – where would we live if a bunch

of strangers moved in here? Have you thought about that at all?’

‘Oh, who cares?’ she said. ‘Anyway, that’s only a minor detail for you – aren’t you in Dublin most of the time?’

From Monday to Friday he worked in the capital, and lived in the apartment he’d bought several years earlier, right in the

centre of the city. Nell had been to it twice, and had no particular wish to return. Their life was on Roone.

‘I spend every weekend here,’ he said. ‘Are you suggesting we camp out on the beach for six weeks?’

She laughed. ‘I would, no problem – God, it would be fabulous – but I can’t see you sleeping under the stars, even for one night.’

‘Well, I’m glad we’re agreed on that at least. As far as I can see, our only option would be to move in with your folks and,

no offence, I’m not sure I’d fancy that.’

‘No …’

She’d already decided that bringing Tim to live in her parents’ house was out of the question. The smallest bedroom had been

converted into her father’s office for years, which left Nell’s old room – and she wouldn’t ask them to let her and Tim sleep

together in there, not when she knew they wouldn’t be comfortable with it. What she did in her own house they accepted was

her business, but under their roof she was happy for their standards to apply.

No need to point that out now, though, when Tim had already vetoed the idea of moving in with them.

‘And James wouldn’t have room for both of us,’ he went on, ‘not that I’d be rushing to stay there either.’

‘I suppose not.’ She’d ruled out James too: his house was small for two, let alone four, although he’d probably have been

fine with it, bless him.

‘So what do you suggest?’ Tim asked. ‘And, yes, it does matter to me where we live. It matters a lot.’

She was going to have to break it gently. ‘Well,’ she said, playing with a button of his flannel shirt, ‘I was thinking of that room off the salon.’

He caught her hand. ‘The room off the salon? You’re not serious. It’s tiny – and it’s full of junk.’

‘Actually, it’s not junk, it’s my supplies. But they could be cleared out, we could make it lovely and cosy.’

‘Cosy is the word,’ he said. ‘Cosy enough not to be able to swing a cat.’

She let a beat pass. ‘How long have you been living in this house?’ she asked.

He looked down at her. ‘About … eight months, isn’t it? What’s that got to do with anything?’

‘In eight months,’ she said, ‘you have never once swung a cat. What makes you think you’d suddenly get the urge if we moved

out?’

‘Be serious.’ He drew away from her and went to look out into the darkness again. She could feel the disapproval coming off

him in waves. He plunged his hands into his pockets, and she heard coins clinking off one another. He always jingled his coins

when he was thinking.

‘You sound like Santa,’ she said. ‘Jingle bells.’

He turned to face her. ‘The whole thing is daft,’ he said. ‘I’ve offered to pay for the wedding. You know I can easily afford

it, but you insist on doing it your way and, frankly, your way just sounds plain daft.’

‘It’s not daft, it’s … innovative,’ she said, damping down a flick of irritation. ‘Look, try to see the big picture. It’s

my wedding day, the only one I’m planning to have, and I’d really love to splash out with a clear conscience. If you were

paying for the whole thing I’d feel like I had to watch what I spent, and just once in my life I want to go mad. Just this

once.’

He shrugged. ‘Still makes no sense to me,’ he said. ‘You could spend what you like, I wouldn’t care. But this is your house,

you’re the boss.’

She resisted the urge to cross the room and slap him, hard. He could be like a two-year-old sometimes. As if she’d lay down

the law because the house they shared had her name on the title deeds, as if she’d ever used her ownership of the house to

her advantage in the eight months since he’d moved in.

At this stage, she considered it as much his house as hers. He paid half the mortgage and the entire electricity bill, and

he’d bought the garden furniture and the bathroom cabinet and the rug in front of the sitting-room fireplace. It was their

house in everything but name – and of course she’d change that when she got around to it.

And she wasn’t trying to lay down the law here, for goodness’ sake – she was just attempting to persuade him, in the gentlest

way possible, to let her contribute to the expense of their wedding. Because there would be expense, a lot of it.

She thought of the dress she’d seen in a Killarney boutique, how it had slithered down over her bra and pants as if all its

life it had been waiting for her to come along and lift it off the hanger. The perfect fit of it, the off-the-shoulder, handmade-silk-flower

sexiness of it – not to mention the colour, which was the palest sea-green: how absolutely perfect was that? Who wanted boring

white on their wedding day, especially if they were lucky enough to live in a place that was surrounded by the sea?

And the teeny triangular buttons tinker-tailoring down the bodice; triangular, not heart-shaped. Nothing sissy about that

dress. That dress had serious attitude.

But attitude didn’t come cheap. Attitude cost almost as much as Nell earned in a month cutting hair – and the bed she wanted

them to begin married life in cost almost as much as the dress. And she was pretty sure that the two-week honeymoon she was

planning would cost much, much more.

Two thousand euro certainly wouldn’t cover everything – it wouldn’t come close. Tim would still be footing most of the bill,

and she had no qualms about that. His computer programmer’s salary was ridiculously high, even during these tighten-your-belt

times. He’d easily cover whatever was left after she’d spent the money they’d get from letting the house.

But she still had to sell the idea to him. She approached him again and leant into his back. ‘I know it’s daft,’ she said, sliding her arms around his chest. ‘I know it’ll be a pain. But

it’ll make me happy, and it’s the only thing I’ve asked you for since we met.’

‘You asked me to stop wearing white socks,’ he said.

She smiled. They were on the right track: he was lightening up. ‘Yes, I did – but that was for your own good. I’d have had

to leave you otherwise, and you would have been heartbroken.’

‘You made me cut my hair.’

‘Again, in your own interest.’

‘And switch to boxers.’

‘Oh, please – ask any woman which she prefers. I can’t believe you got away with those other horrors for so long.’

He turned to face her at last. He cupped her chin in his hand. ‘I wish I didn’t love you,’ he said. ‘Life was so much easier

before we met.’

She laughed. ‘Come on, you don’t expect me to believe that. I’m the best thing that ever happened to you.’

He pulled her into his chest. She took that as agreement. ‘We’re getting married,’ she said, pressing against him and closing her eyes, hearing the gentle rattle of his breathing beneath the shirt and the

thermal vest, smelling the comforting warmth of the eucalyptus-scented ointment she’d smeared earlier on his chest. ‘It’ll

be worth it, I promise. We’ll have the perfect wedding and honeymoon, and I’ll never ask you for another thing.’

‘Can I have that in writing?’

‘You’re joking, aren’t you?’ She stood on tiptoe and kissed his cheek. ‘I’ll show you the website I found. It’s very safe.

We can dictate all the conditions, say what’s allowed and what’s not. Pets or no pets, that kind of thing. And no smoking,

obviously.’

‘Smoking?’ he asked sharply, drawing back. ‘We could get smokers staying here?’

Damn. Three steps forward, two back.

‘No, we couldn’t. We’d make it clear that smoking in the house wasn’t on. People are used to it now – everyone goes outside

to smoke. That wouldn’t be a problem at all.’

It was two days before Christmas. In just under a year she would stop being Nell Mulcahy and start being Nell Baker. She loved the idea of taking his name and making it hers – and Mrs Baker

sounded so cosy. Mrs Baker had rosy cheeks and wore a checked apron and made the best apple tarts in town. All the children

loved Mrs Baker because she gave them homemade lemonade and chocolate-chip cookies when they called round.

‘Do you think children prefer chocolate-chip cookies or cupcakes?’ she asked.

‘What?’

‘Nothing.’

‘So,’ he said, ‘you’re proposing that we both squeeze into that tiny room at the weekends.’

‘Well, if you really hate the thought of it you could ask James if you could stay with him. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind.’

They weren’t close, not the way Nell imagined two siblings should be. At forty, James was five years older than Tim. He lived

with his son in a house that had been built as a holiday home, with small rooms and little storage space, but he and Andy

seemed to manage fine. And they had three bedrooms, so there would be room for Tim.

‘You could talk to James,’ she said. ‘Just put it to him and see how he reacts.’ It wasn’t as if they didn’t get on, they

were just very different. ‘But I’d miss you.’

‘Would you?’

‘Course I would.’

Nell and James got on wonderfully well. He was quieter than Tim, and creative where Tim was logical. He painted houses around

the island and beyond, and occasionally he worked behind the bar in Fitz’s. And when he wasn’t painting walls he painted canvases,

with considerable skill. His work was on sale in various locations around the country – including, of course, the island’s

two art galleries – and Nell had a small collection on display in her hair salon. When she and Tim had got engaged James had

presented them with a view of the old harbour which was quite beautiful, and which hung above their bed.

‘OK,’ Tim said.

She drew back to look into his face. ‘OK? OK what?’

‘We can try the little room,’ he said. ‘We can give it a go.’

‘Only if you’re sure,’ she said, trying not to look triumphant.

She’d won. She’d got what she wanted. They were on the way to the perfect wedding, followed by the bit where they got to live

happily ever after. Mr and Mrs Baker and their large, cheerful family. She planned at least four children, as close in age

as she could manage. More, if the humour took her. The biggest family on Roone they might have. ‘I don’t know how Mrs Baker

does it,’ everyone would say. ‘All those children, and still managing that hair salon and baking all those apple tarts.’

Tim sighed deeply. ‘I think,’ he said, ‘it’s going to be a long summer.’

‘Not at all,’ the future Mrs Baker replied, smiling up at him. ‘It’ll fly by. Wait and see.’

Katy –

Big news: we’re letting the house for the summer! Well, just for six weeks, which should net us over two grand, would you

believe? Looks like I’ll get the wedding of my dreams after all! Tim not bowled over with the idea but going along to keep

me happy, bless him. So in January we’ll register with a holiday-home letting website and see what happens – watch this space!

Hope all’s well, happy new year, let’s hope it’s a good one!

N xxx

Nell

Letting the house, great idea – maybe I’ll book it myself and FINALLY get to meet you! Keep me posted – and on all the wedding

plans, of course. I’m back at work already, no rest for the wicked, but there’s a big company party planned for the 31st,

so I’ll be ringing in the new year with a splash … and hopefully not holding my head for too long afterwards! Happy new year

to you and Tim,

K xxx

‘They’re asking for a security question,’ Nell said. ‘They want the name of my first best friend, or my mother’s maiden name,

or my favourite movie star.’

‘I should choose my mother’s maiden name,’ Walter replied. ‘The others are all subjective, whereas that one is a constant.

You won’t be trying to remember which person you decided was your best friend, and so on.’

‘True.’ She clicked on the mouse and began to type. ‘Should I write Fitzpatrick with a capital “F”?’

‘Oh, yes. Write it exactly how you always do, and that way you won’t be wondering.’

She smiled at him. ‘I knew you’d be the best person to help me with this.’

Walter wondered privately why she didn’t regard her fiancé – who was, after all, far more au fait with computers than Walter

– as the most suitable person to help her fill in a form that was located on a computer screen, but he held his tongue. No

doubt she had her reasons.

‘Right, property description – there’s a checklist. One bathroom, two bedrooms, zero en-suites, zero cots available for infants,

number of seats in dining room —’ She looked up. ‘I don’t have a dining room.’

‘In that case, put in the number of seats in your kitchen,’ Walter said. ‘Wherever you eat, I should think.’

‘Oh, right. We have only four kitchen chairs – but I could borrow one or two from Mam and Dad. Then again, the house only

sleeps four.’

‘Perhaps your couch could sleep a fifth?’

She looked doubtful. ‘Well, we have had the odd pal spending the night on it, but only for a weekend, and they weren’t paying.

I’m not sure I’d fancy sleeping on it myself.’

‘I should leave it at four then.’

‘Yes, four is plenty, so four chairs will do.’ She scrolled down. ‘Maximum number of people accepted – four.’ She stopped

again. ‘Does four sound too few, though? Am I limiting my chances of getting people?’

‘Not at all. A couple, or a couple and two children, or a small group of friends. Plenty of scope, I should think.’

‘OK, four it is then … Next is external features. What external features have I?’

‘Patio with furniture,’ Walter offered. ‘Front and rear landscaped gardens.’

‘Doesn’t sound very exciting, does it? Maybe I could get a barbecue. Must ask James where he got his … Right, here’s a box

for additional information. What can we add?’

‘Scenic island location. Adjacent to beautiful beach.’

‘Is half a mile adjacent?’

‘Absolutely. Walking distance to village with shops, pubs, cafés. Numerous walks, suitable for cyclists, tourist attractions

such as lighthouse, prehistoric remains, holy well—’

‘Slow down.’ She tapped the keys rapidly. ‘Right, holiday type, another checklist. Let’s see … not city, not winter sun, not

ski. Yes, beach, yes, relaxing, yes, walking holiday, yes, village, yes, waterfront, yes, seaside. That should do it.’

‘Another sherry?’ Walter asked, sneaking a look at the clock on the opposite wall.

Nell shook her head. ‘Better not, thanks … Sports and activities, oh dear, no horse riding, no golf, no tennis, no skiing,

no pony trekking – oh, thank goodness, fishing, cycling, surfing, walking. I thought I wasn’t going to be able to tick any

of the boxes.’

They made their way through arrival details, availability and rental rates, and then Walter decided the time had come to speak

up. ‘In fact,’ he said apologetically, ‘it’s getting on for one o’clock, so perhaps we’d better—’

‘Lord, it’s not, is it?’ Nell flipped the laptop closed. ‘Sorry, Walter, I lost track. Come on, I’ll grab my books and meet

you outside.’

The mobile library visited Roone every Monday and parked on the main street for two hours from eleven till one. Nell and Walter rarely missed a visit, being equally greedy bookworms,

even if Walter’s literary tastes ran more towards gardening and biographies, and Nell favoured whodunits and historical romances.

Nell covered the mile to the village in her yellow Beetle far too quickly for Walter’s heart, but thankfully, the night’s

subzero temperatures hadn’t caused problems on the dry roads, and they made it safely with minutes to choose their new books.

Walter opted to walk home afterwards, saying he needed one or two things in the supermarket.

‘Oh, but I’ll wait for you.’

‘No need,’ he assured her. ‘The walk will do me good.’

‘Well, let me take your books at least, I’ll drop them over later – or will you come to dinner tonight? Oh, do, I’m trying

out a beef casserole, with apricots. Come around seven.’

She was the best of neighbours, generous and reliable. He’d miss having her around for six weeks. Not that she’d be gone far,

of course – nowhere was far on Roone. And it might be interesting to have new faces across the stone wall from him, just for

a little while.

He walked along the village street, humming the first few bars of ‘Three Little Maids From School Are We’, and wondering what

business apricots could possibly have in a beef casserole.

‘Tim,’ his boss said, ‘how’s the Dickinson job coming along?’

Tim clicked an icon on his screen and a new dialogue box popped up. ‘Fine. Should have it for you by end of play on Thursday.’

‘Any hope of a bit earlier? I’ve just had a call from Liam Heneghan at Slattery’s – a few of them are coming in to talk to

us first thing on Wednesday about overhauling their system, and you know they always want things done yesterday.’

Earlier than Thursday wo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...