- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

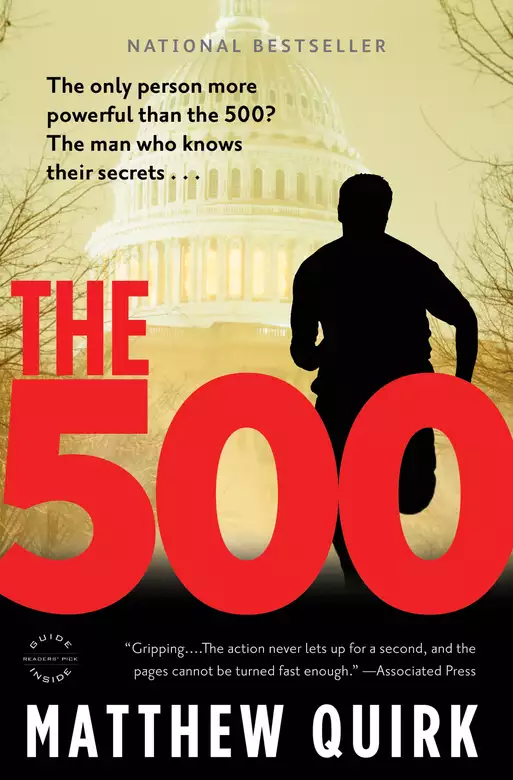

Synopsis

A year ago, fresh out of Harvard Law School, Mike Ford landed his dream job at the Davies Group, Washington’s most powerful consulting firm. Now he’s staring down the barrel of a gun, pursued by two of the world’s most dangerous men. To get out, he’ll have to do all the things he thought he’d never do again: lie, cheat, steal—and this time, maybe even kill. Mike grew up in a world of small stakes con men, learning lessons at his father’s knee. His hard won success in college and law school was his ticket out. As the Davies Group’s rising star, he rubs shoulders with “The 500,” the elite men and women who really run Washington—and the world. But peddling influence, he soon learns, is familiar work and even with a pedigree, a con is still a con. Combining the best elements of political intrigue and heart-stopping action, The 500 is an explosive debut, one that calls to mind classic thrillers like The Firm and Presumed Innocent. In Mike Ford, listeners will discover a new hero who learns that the higher the climb, the harder—and deadlier—the fall.

Release date: June 5, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The 500

Matthew Quirk

MIROSLAV AND ALEKSANDAR filled the front seats of the Range Rover across the street. They wore their customary diplomatic uniforms—dark Brionis tailored close—but the two Serbs looked angrier than usual. Aleksandar lifted his right hand high enough to flash me a glint of his Sig Sauer. A master of subtlety, that Alex. I wasn’t particularly worried about the two bruisers sitting up front, however. The worst thing they could do was kill me, and right now that looked like one of my better options.

The rear window rolled down and there was Rado, glaring. He preferred to make his threats with a dinner napkin. He lifted one up and dabbed gently at the corners of his mouth. They called him the King of Hearts because, well, he ate people’s hearts. The way I heard it was that he’d read an article in the Economist about some nineteen-year-old Liberian warlord with a taste for human flesh. Rado decided that sort of flagrant evil would give his criminal brand the edge it needed in a crowded global marketplace, so he picked up the habit.

I wasn’t even all that worried about him tucking into my heart. That’s usually fatal and, like I said, would greatly simplify my dilemma. The problem was that he knew about Annie. And my getting another loved one killed because of my mistakes was one of the things that made Rado’s fork look like the easy out.

I nodded to Rado and started up the street. It was a beautiful May morning in the nation’s capital, with a sky like blue porcelain. The blood that had soaked through my shirt was drying, stiff and scratchy. My left foot dragged on the asphalt. My knee had swollen to the size of a rugby ball. I tried to concentrate on the knee to keep my mind off the injury to my chest, because if I thought about that—not the pain so much as the sheer creepiness of it—I was sure I would pass out.

As I approached, the office looked as classy as ever: a three-story Federal mansion set back in the woods of Kalorama, among the embassies and chanceries. It was home to the Davies Group, Washington, DC’s most respected strategic consulting and government affairs firm, where I guess technically I may have still been employed. I fished my keys from my pocket and waved them in front of a gray pad beside the door lock. No go.

But Davies was expecting me. I looked up at the closed-circuit camera. The lock buzzed.

Inside the foyer, I greeted the head of security and noted the baby Glock he’d pulled from its holster and was holding tight near his thigh. Then I turned to Marcus, my boss, and nodded by way of hello. He stood on the other side of the metal detector, waved me through, then frisked me neck to ankle. He was checking for weapons, and for wires. Marcus had made a nice long career with those hands, killing.

“Strip,” Marcus said. I obliged, shirt and pants. Even Marcus winced when he saw the skin of my chest, puckering around the staples. He took a quick look inside my drawers, then seemed satisfied I wasn’t bugged. I suited back up.

“Envelope,” he said, and gestured to the manila one I was carrying.

“Not until we have a deal,” I said. The envelope was the only thing keeping me alive, so I was a little reluctant to let it go. “This will go wide if I disappear.”

Marcus nodded. That kind of insurance was standard industry practice. He’d taught me so himself. He led me upstairs to Davies’s office and stood guard by the door as I stepped inside.

There, standing by the windows, looking out over downtown DC, was the one thing I was worried about, the option that seemed much worse than getting carved up by Rado: it was Davies, who turned to me with a grandfather’s smile.

“It’s good to see you, Mike. I’m glad you decided to come back to us.”

He wanted a deal. He wanted to feel like he owned me again. And that’s what I was afraid of more than anything else, that I would say yes.

“I don’t know how things got this bad,” he said. “Your father…I’m sorry.”

Dead, as of last night. Marcus’s handiwork.

“I want you to know we didn’t have anything to do with that.”

I said nothing.

“You might want to ask your Serbian friends about it. We can protect you, Mike; we can protect the people you love.” He told me to sit down at the far end of the conference table, and he moved a little closer. “Just say it and all this is over. Come back to us, Mike. It only takes one word: yes.”

And that was the weird thing about all his games, all the torture. At the end of the day he really thought he was doing me a favor. He wanted me back, thought of me as a son, a younger version of himself. He had to corrupt me, to own me, or else everything he believed, his whole sordid world, was a lie.

My dad chose to die instead of playing ball with Davies. Die proud rather than live corrupted. He got out. It was so neat and clean. But I didn’t have that luxury. My death would be only the beginning of the pain. I had no good options. That’s why I was here, about to shake hands with the devil.

I placed the envelope on the table. Inside it was the only thing Henry was afraid of: evidence of a mostly forgotten murder. His only mistake. The one bit of carelessness in Davies’s long career. It was a piece of himself he’d lost fifty years before, and he wanted it back.

“This is the only real trust, Mike. When two people know each other’s secrets. When they have each other cornered. Mutually assured destruction. Anything else is bullshit sentimentality. I’m proud of you. It’s the same play I made when I was starting out.”

Henry always told me that every man has his price. He’d found mine. If I said yes, I’d have my life back—the house, the money, the friends, the respectable facade I’d always wanted. If I said no, it was all over, for me, for Annie.

“Name your price, Mike. You can have it. Anyone who’s anyone has made a deal like this on the way up. It’s how the game is played. What do you say?”

It was an old bargain. Swap your soul for all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. There would be haggling over details, of course. I wasn’t going to sell myself on the cheap, but that was quickly squared away.

“I will give you this evidence,” I said, tapping my finger on the envelope, “and guarantee that you will never have to worry about it again. In exchange, Rado goes away. The police leave me alone. I get my life back. And I become a full partner.”

“And from now on, you’re mine,” Henry said. “A full partner in the wet work too. When we find Rado, you’ll slit his throat.”

I nodded.

“Then we’re agreed,” Henry said. The devil held his hand out.

I shook it, and handed over my soul with the envelope.

But that was bullshit, another gamble. Die in infamy, honor intact, or live in glory, corrupted. I chose neither. There was nothing in the envelope. I was trying to barter empty-handed with the devil, so I really had only one choice: to beat him at his own game.

CHAPTER ONE

I WAS LATE. I checked myself out in one of the giant gilt mirrors they had hanging everywhere. There were dark circles under my eyes from lack of sleep and a fresh patch of carpet burn on my forehead. Otherwise I looked like every other upwardly mobile grade-grubber streaming through Langdell Hall.

The seminar was called Politics and Strategy. I ducked inside. It was application only—sixteen spots—and had the reputation of being a launching pad for future leaders in finance, diplomacy, military, and government. Every year Harvard tapped a few mid- to late-career heavies from DC and New York and brought them up to lead the seminar. The class was essentially a chance for the wannabe big-deal professional students—and there was no shortage of them around campus—to show off their “big think” skills, hoping establishment dons would tap them and start them off on glittering careers. I looked around the table: hotshots from the law school, econ, philosophy, even a couple MD/PhDs. Ego poured through the room like central air.

It was my third year at the law school—I was doing a joint law and politics degree—and I had no idea how I’d managed to finagle my way into HLS or the seminar. That’d been pretty typical of the past ten years of my life, though, so I shrugged it off. Maybe it was all just a long series of clerical errors. My usual attitude was the fewer questions asked, the better.

Jacket, button-down, khakis: I mostly managed to look the part, if a little worn and frayed. We were in the thick of the conversation. The subject was World War I. And Professor Davies stared at us expectantly, sweating the answer out of us like an inquisitor.

“So,” Davies said. “Gavrilo Princip steps forward and pistol-whips a bystander with his little Browning 1910. He shoots the archduke in the jugular and then shoots his wife through the stomach as she shields the archduke with her body. He just so happens to trigger the Great War in the process. The question is: Why?”

He glowered around the table. “Don’t regurgitate what you read. Think.”

I watched the others squirm. Davies definitely qualified as a heavy. The other students in class had studied his career with jealous obsession. I knew less, but enough. He was an old Washington hand. Going back forty years, he knew everyone who mattered, the two layers of people below those who mattered, and, most important, where all the bodies were buried. He’d worked for Lyndon Johnson, jumped ship to Nixon, then put out his own shingle as a fixer. He now ran a high-end strategic consulting firm called the Davies Group, which always made me think of the Kinks (that should tell you a bit about how fit I am for cutthroat DC career climbing). Davies had influence and could trade on that for anything he wanted, including, as one of the guys in class pointed out, a mansion in McLean, a place in Tuscany, and a ten-thousand-acre ranch on the central California coast. He’d been guest-teaching the seminar for a few weeks now. My classmates were practically vibrating with anxiety; I’d never seen them so eager to impress. That led me to believe that in the various orbits of official Washington, Davies had pull like the sun.

Davies’s usual teaching method was to sit placidly and put a good face on his boredom, like he was listening to a bunch of second-graders spout dinosaur trivia. He wasn’t an especially large man, maybe five ten, five eleven, but he sort of…loomed. His pull, it was almost like you could see it spread out through a room. People stopped talking, all eyes turned to him, and soon enough he had everyone lined up around him like filings around a magnet.

But his voice: that was the odd thing. You’d expect it to boom out, but he always spoke softly. There was a scar on his neck, right between where his jawline met his ear. It was the source of some speculation, whether an old injury had something to do with his quiet tone, but no one knew what had happened. It didn’t matter much, since most rooms went silent when he opened his mouth. In class, though, his students were desperate to be heard, to be noticed by the master. Everyone had his answers to Davies’s questions marshaled. There’s an art to seminar: when to let others blabber, when to cut in. It’s like boxing or…I guess fencing or squash or one of those other Ivy League pastimes.

The guy who always went first and never had a point to make began talking about the Young Bosnia movement until Davies’s stare put the fear in him. The kid trailed off, mumbling. A feeding frenzy ensued as everyone smelled weakness and started barking over one another, spouting off about Greater Serbia versus the Southern Slavs, Bosnian versus Bosniak, irredentist Serbs and the Triple Entente and the two-power standard.

I was in awe. It wasn’t just the facts they’d assembled (and some of these guys seemed to know literally everything; I’d never managed to push them out of their depths). It was their manner. You could see the entitlement in every move; it was like they’d grown up toddling around the study as their fathers swirled single-malts and debated the fate of nations, like they’d spent the last twenty-five years boning up on diplomatic history just to kill time until their dads grew tired of running the world and let them take the wheel. They were just so…so goddamn respectable. I usually loved to watch them, loved the little toehold I’d managed to gain in this world, loved to think that I could finally pass for one of them.

But not today. I was having trouble. I couldn’t keep up with the give-and-take, the points and parries, let alone outdo them. On my good days I had a chance. But every time I tried to think about century-old Balkan micropolitics, I only saw a number, big and red and flashing. It was written in my notebook: $83,359, circled and underlined, and followed by a few other numbers: 43-23-65.

I hadn’t slept the night before. After work—I tended bar at a yuppie place called Barley—I went over to Kendra’s. I figured taking her up on her come-fuck-me look at the bar would do me more good than the ninety minutes of sleep I might have gotten before I had to wake up and read twelve hundred pages of densely written IR theory. She had black hair you could drown in, and a shape that invited lewd thoughts. But the principal appeal may have been that girls named Kendra who worked for tips and didn’t look you in the eye in bed were the exact opposite of everything I told myself I wanted.

I headed out from Kendra’s and got home around seven that morning. I knew something was up when I saw a few of my T-shirts on the stoop and my dad’s ratty old Barcalounger lying on its side on the sidewalk. The front door to my apartment had been forced, and not well. It looked like a mean black bear had done it. Gone: my bed, and most of the furniture, the lamps and small kitchen appliances. The rest of my stuff was scattered everywhere.

People were going through my shit on the sidewalk like it was the giveaway at the end of a yard sale. I shooed them off and gathered up what was left. The Barcalounger was safe: it weighed as much as a hatchback and would require some serious forethought and a couple of guys to haul it off.

As I straightened up inside the apartment, I noticed that Crenshaw Collection Services hadn’t seen the value of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War or the five-inch-thick stack of reading material that had to be finished before seminar in two hours. They had left me a little love note on the kitchen table: Furnishings taken as partial payment. Outstanding balance: $83,359. Outstanding. Spectacular, even. I knew enough law by then to recognize at a glance about seventeen fatal flaws in Crenshaw’s approach to debt collection, but they were as ruthless as bedbugs and I’d been too slammed trying to pay for school to sue them to a pulp. But that day would come.

Your parents’ debts are supposed to die with them, settled out of the estate. Not mine. The eighty-three grand was the balance due for my mother’s stomach cancer treatment. She was gone now. And if I may share one piece of advice, it’s this: if your mother is dying, don’t ever pay her bills with your own checkbook.

Because some unsavory creditors, folks like Crenshaw, will take that as a pretext to come after you once she’s dead. You’ve tacitly assumed the debts, they’ll say. It’s not exactly legal. But it’s not the kind of thing you know to look out for when you’re sixteen and the radiology bills start coming in and you’re trying to keep your mom alive by working overtime at Milwaukee Frozen Custard and your dad’s doing a twenty-four-year bid at the Allenwood Federal Correctional Complex.

I’d been through this sort of hassle too often to even waste time with anger. I’d do what I always did. The more all that stuff from the past tried to drag me down, the more I’d work my ass off to rise above it. And that meant putting a wall around this little disaster, meant plowing through as much work as I could before class so I wouldn’t sound like a moron in Davies’s seminar. I took my reading out to the sidewalk, then righted the recliner. I kicked back and dug into some Churchill essays as traffic cruised by.

By the time I made it to seminar, however, I’d crashed. My punchy up-all-night post-lay energy was gone, as was the jolt of enthusiasm I’d had to spite Crenshaw by nailing class. To get to seminar, I had to swipe my ID at the entrance to Langdell Hall. I joined the long queue of students swiping and hitting the turnstiles and hustling to class. But my card made the LED flash red, not green. The metal bar locked and bent my knees back. My upper half continued forward in one of those agonizingly slow falls where you realize what’s happening and can’t do a thing about it for the ten minutes it seems to take to eat shit headfirst onto a thin layer of carpet over cement.

The cute undergrad behind the circulation desk was nice enough to explain that I might want to check with the Student Receivables Office about unpaid tuition or fees. Then she treated herself to a little pump of hand sanitizer. Crenshaw must have gone after my bank accounts and screwed up my tuition payment, and Harvard was just as serious about getting paid as Crenshaw. I had to circle around the back of Langdell and sneak in behind a guy going out for a smoke by the shipping dock.

In class, I guess my fugue state was now pretty obvious. It felt like Davies was looking right at me. Then I felt it coming. I fought it with every muscle in my body but sometimes there’s nothing you can do. I had to yawn. And this one was big, lion big. There was no hiding it behind my hand.

Davies fixed me with a dagger look sharpened over God knows how many face-offs—he used to stare down labor bosses and KGB agents.

“Are we boring you, Mr. Ford?” he asked.

“No, sir.” An awful weightless feeling grew in my stomach. “I apologize.”

“Then why don’t you share your thoughts on the assassination?”

The others tried to hide their delight: one less grade-grubber to climb over. The particular thoughts distracting me went like this: Can’t shake Crenshaw until I have a law degree and a decent job and can’t get either until I shake Crenshaw, which leaves me with the eighty-three grand due Crenshaw and one hundred sixty due Harvard and no way to pay it back. Everything I’d worked my ass off for ten years to earn, all the respectability filling that room, was about to slip from my hands, and be gone for good. And at the root of it all: my father, the convict, who first got tangled up with Crenshaw, who left me the man of the house at twelve, who should have done the world a favor and kicked instead of my mom. I pictured him, pictured his smirk, and as much as I tried not to, all I could think about was…

“Revenge,” I said.

Davies brought the earpiece of his glasses up to his lips. He was waiting for me to go on.

“I mean Princip is dirt-poor, right? He has six siblings die, and his parents have to give him away because they can’t feed him. And he thinks the whole reason he can’t get ahead in life is that the Austrians have had their foot on his family’s neck since he was born. He’s scrawny; the guerrillas laughed him out of the room when he tried to join up. He was just a nobody trying to make a splash. The other assassins lost their nerve, but he…he was, well, pissed off like no one else. He had something to prove. Twenty-three years of resentment. So he’d do what he had to do to make his name, even if it meant killing. Especially if it meant killing. The more dangerous the target the better.”

My peers looked away in distaste. I didn’t talk much in seminar, and when I did I tried to use polished, high-sounding Harvard English like everyone else, not the regular-Mike tone I had just slipped into. I waited for Davies to tear me up. I sounded like a street kid, not a young establishment comer.

“Not bad,” he said. He thought for a moment, then looked around the room.

“Grand strategy, world war. You are all getting caught up in abstractions. Never lose sight of the fact that at the end of the day it comes down to men. Someone has to pull the trigger. If you want to lead nations, you have to start by understanding a single man, his wants and fears, the secrets he won’t admit to and may not even be aware of himself. Those are the levers that move the world. Every man has a price. And once you find it, you own him, body and soul.”

After class, I was in a rush to clean myself up and attend to the disaster back in my apartment. A hand on my shoulder stopped me. I half expected it to be Crenshaw, ready to humiliate me in front of the good people of Harvard.

That might’ve been preferable; it was Davies, with that dagger stare and whisper voice. “I would like to talk to you,” he said. “Ten forty-five, my office?”

“Terrific,” I said, my best attempt at calm. Maybe he’d saved the chewing-out for a private conference. Classy.

I needed food and sleep, but coffee would cover both for a while. I didn’t have time to go back to my apartment, and without really thinking about it, I walked over to Barley, the bar where I worked. The only thing filling my head was that number, $83,359, and the endless pathetic arithmetic of how I’d never be able to pay it off.

The bar was a pretentious box with too many windows. The only one in there was Oz, the manager, who bartended a few shifts a week. It wasn’t until I leaned against the oak bar and took the first bitter sip of coffee that I caught myself. I hadn’t come for caffeine. I cycled the numbers in my head: 46-79-35, 43-23-65, and so on. They were combinations for a Sentry safe.

Oz, who was also the owner’s son-in-law, was skimming. And not just here and there, the usual retail “shrinkage.” He was robbing the place. I’d been watching him up his game for a while, no sale–ing drinks and pocketing the money, comping his regulars half their tabs and never punching a thing into the register. Fishing that large a volume of stolen money from the cash drawer every night must have been a little difficult, since he had to do it while we were waiting around to be tipped out. So I was certain, dead certain, that this asshole was now keeping it in the safe. I could just tell. Probably because his act was basically a clumsy version of what I’d be doing if I were him and hadn’t sworn off grifting a long time ago. The academic term is alert opportunism. It means that if you have the eyes of a criminal, you see the world differently, as nothing more than a collection of unwatched candy jars. I was starting to worry about myself, because now that I needed money, badly, it was all jumping out at me again: unlocked cars, open doors, loose purses, cheap locks, dark entries.

As much as I tried, I couldn’t forget my apprenticeship, my ill-gotten expertise. I couldn’t ignore all those invitations to stray. People seem to think thieves have to pick locks and shinny up drainpipes and charm widows. Usually, though, they just have to keep their eyes open. The money is more or less left sitting out by honest folks who can’t quite believe people like me are walking around. The hidden key, the unlocked garage, the anniversary-date PIN code. It’s there for the taking. And that’s the funny thing: the straighter I became, the easier it was to be crooked. It was like people were constantly upping the temptations to keep testing me after all these years clean. As a harmless-looking grad student in a button-down, I could probably have walked out of Cambridge Savings and Trust with a trash bag full of hundreds and a revolver in my belt while the guard held the door and told me to have a nice weekend.

Alert opportunism. That’s how I picked up that Oz was day-locking the safe, so he only had to dial in the last number to open it. It’s how I knew that that number was 65. It’s how I recalled that Sentry safes came from the manufacturer preset with only a handful of codes—called tryouts—and so if Oz’s code ended in 65, it was almost certain that someone along the line had been too lazy to change the original factory combo from 43-23-65. It’s how I noted that Oz was barely able to calculate a tip, let alone keep his skim straight, and that his drinking had gone from bad to worse: at 10:30 a.m. he was already halfway through a five-second pour of Jameson in a mug with a splash of coffee on top. And even if he did notice something missing, who would he tell? No honor among thieves, right?

Oz had the cash drawers on the bar now. He took them into the office. I heard the safe open and shut. He came back out and said, “I’m going to grab some cigarettes. Can you keep an eye on the place?”

Opportunity knocked. I nodded.

I took my coffee, stepped into the office, and tried the handle on the safe. It was open. Jesus. He was practically begging me. Scanning the contents, I counted about forty-eight thousand dollars in bank bundles and maybe another ten grand or so in cash just piled up. Oz was way behind on the deposits.

There were two plays: I could nibble away at his skim and keep Crenshaw off my back long enough to get my degree. Or I could just rip off the Band-Aid, come in before dawn and clean it out. The bar’s back door was like Fort Knox, but the front you could pry open with a Wonderbar in a minute and a half—typical. No one would get hurt. As long as there are signs of forced entry, insurance pays out. I checked the top drawers of the desk, then the corkboard, and sure enough, there it was, tacked to the wall in Oz’s third-grader handwriting: 43-23-65—the combination. Begging me.

I needed to pay Harvard at least, that week. Or else no degree. All that work, gone. The blood was pumping. A thrill coursed through me. It felt good. Really good. I’d missed it. Ten years I’d been clean, the upstanding go-getter. I hadn’t strayed, hadn’t lifted so much as a malted-milk ball from the grocery-store candy bins.

Standing in front of that open safe felt good. It felt way too good. It was in my blood. And I knew that shit would destroy me—like it did my dad, like it did my family—if I gave it the slightest chance. I looked over my button-down shirt, my loafers, Thucydides staring up from the cover of my book.

“Fuck me,” I muttered. Who was I kidding? I was too damn respectable to be crooked. And somehow still too crooked to be respectable. I swallowed the last of my coffee, then looked down at the empty mug. I’d chosen honest a long time ago, to survive, and I was going to stick with it even if it killed me.

I clanked the safe door shut.

I had pictured Davies’s office like a World War II film set: a map room with man-size globes and him shoving around armies on table maps with a croupier’s rake. Instead, Harvard had put him in a spare office in Littauer Hall, all Office Depot cherry veneer and no windows.

Sitting across from him, I felt an eerie bit of déjà vu. He seemed to grow as he looked me over, and I remembered, from a long time ago, what it was like to be standing dead center in the courtroom with a judge staring down.

“I have to catch the shuttle back to DC in a few minutes,” Davies said. “But I wanted to talk to you. You were a summer associate at Damrosch and Cox?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’re planning to work with them after you graduate?”

“No,” I said.

That’s pretty unusual. All the real work in law school is in the first year and a half, when you’re gunning for a summer associateship at a firm. Then they wine and dine and overpay you to do nothing in order to make up for the seven years of hell they’re going to make you pay as an actu. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...