- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

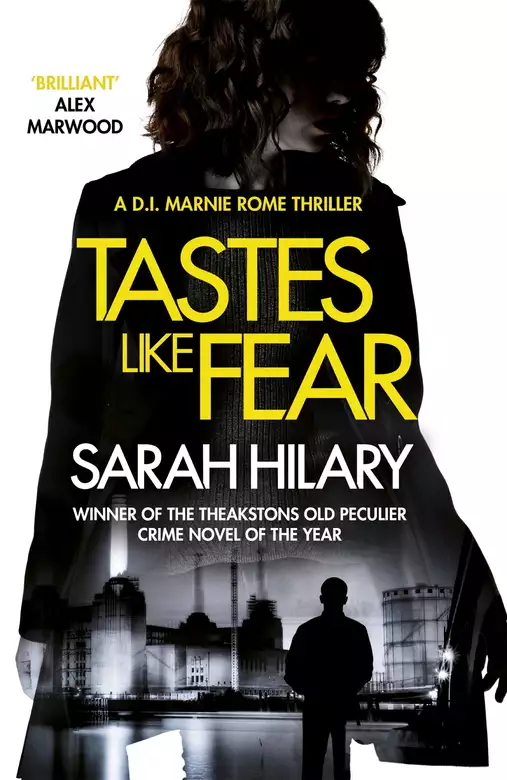

Sarah Hilary won the 2015 Theakston's Crime Novel of the Year with her debut, the 2014 Richard and Judy pick. She followed up with NO OTHER DARKNESS, proclaimed as 'riveting' by Lisa Gardner, 'utterly gripping' by Eva Dolan and 'truly mesmerising' by David Mark. Now D.I. Marnie Rome returns in her third novel.

You'll never be out of Harm's way

The young girl who causes the fatal car crash disappears from the scene.

A runaway who doesn't want to be found, she only wants to go home.

To the one man who understands her.

Gives her shelter.

Just as he gives shelter to the other lost girls who live in his house.

He's the head of her new family.

He's Harm.

D.I. Marnie Rome has faced many dangerous criminals but she has never come up against a man like Harm. She thinks that she knows families, their secrets and their fault lines. But as she begins investigating the girl's disappearance nothing can prepare her for what she's about to face.

Because when Harm's family is threatened, everything tastes like fear...

Release date: April 7, 2016

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 330

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Tastes Like Fear

Sarah Hilary

The rain found its way into everything, bleeding through brickwork, shaking the glass from broken windows, filling the empty can Christie put out for the rush hour. She ran her finger around its ragged lip, inviting blood – proof that she was still here. A Guinness can, its top taken off with a blunt knife, stones weighting the bottom. Coins did the same trick, but it’d been days since anyone dropped coins. She sucked at her finger, tasting meat and copper. Raw inside, an empty ache, but I’m still here, she thought. She wished she had better proof than a bloody finger in her mouth.

The world was a wall of umbrellas. She knew the commuters on this route, had seen them sweating in their summer dresses and shirtsleeves. Scowling now, heads down, shoulders up. Angry at her for taking up space on their pavement, sticking her dirty feet in the half-shut door of their conscience. The rain was an excuse to hate her more than they already did.

When she was new to this game – how long ago? Months? – she’d searched the crowd for kind faces. But she’d quickly learned it wasn’t kindness that gave coin. People threw change at her the way they’d toss it at a toll-gate basket. To get past, away. Soon, they wouldn’t have to pretend not to notice her. She’d be see-through. The rain was washing her away.

‘Do you mind?’ a woman demanded, meaning Christie’s feet, which were in her way apparently, even though they weren’t. She’d made herself so small, no part of her was in anyone’s way. ‘For God’s sake find yourself somewhere to go.’ Thin and furious, her fist fierce with rings, clenched around the handle of a yellow umbrella.

Christie had tucked herself into a doorway where it was almost dry, but the rain still found her. Pricking through old bricks, a trickle and then a stream. She felt its fingers tickling her neck.

‘There are places, you know.’

She didn’t know. She wished she did. She was scared of the rain, the way it ruined everything, her clothes, her sleeping bag – everything she had. Rain scared her worse than fire.

When she was new to this, a young couple would come with leaflets. They’d stop and crouch, faces working hard. Talking about Our Lord and what was coming and ‘Are you ready?’ Christie expected it from old people, though most shook their heads as if beggars hadn’t existed back in their day. Only once did anyone over the age of sixty give her a second glance. The young couple had pamphlets with pictures of grinning people. The colours ran, making her hands dirtier. When she asked for money, they got mad. They pretended they weren’t – ‘We’re on your side’ – but she saw it under the surface of their skin like a swallowing of snakes.

Worse than the snakes was the little man who came and sat beside her. He never spoke, just sat dropping change into her can, one penny at a time, so she couldn’t get up and go or tell him to piss off even though he was freaking her out. He smelt funny. Not poor-funny. Rich-funny. Being rich didn’t help, the young couple said, it was about being ready for what was coming. Death or Jesus, she didn’t know, but there was a whole moment when she thought she could do it – pretend to be religious so they’d save her from this. Being nobody, nothing, invisible.

When the rain started, they stopped coming.

Everyone stopped, except the little man. In a plastic cape that ran the wet off him into her doorway. Splashing coppers into her can, and she knew she couldn’t afford to be picky but when he went, she shoved her hand in and scooped out his coins, flinging them away from her, sucking rusty blood from her knuckles. He’d be back for more tomorrow. She should move, somewhere he couldn’t find her. Her whole body hurt like it was being squeezed.

Where would she go?

Who should she be?

She could make herself smaller for the woman with the rings, pretend to believe in Jesus for the religious couple. Go with the creep in the cape and be … whatever he wanted her to be. Just to get out of the rain for a day, an hour. It was washing her away, all her colours, everything. She wasn’t her any more. Empty inside, scraped out. Missing.

That was when he found her, where he found her …

Right on the brink of being lost.

He wasn’t like the little man. He was tall and fair and he smelt of the rain that was bluing the shoulders of his shirt. He didn’t have pamphlets, or questions. He wasn’t angry with her.

His hands were empty and open, like his face.

When he stood in her doorway, he blocked the umbrellas and the hiss and spit of tyres in the street. His shoulders stopped the rain from reaching her.

Strong fingers, wet like hers, but his palms were dry and warm.

Safe, he was safe.

There are places, you know.

She hadn’t believed it, until then.

Praise for Tastes Like Fear:

‘Brilliant. I put everything else aside when I have one of her books in the house’ Alex Marwood

‘A tense, terrifying tale of obsession and possession … a writer at the top of her game’ Alison Graham, Radio Times

‘A truly chilling exploration of control, submission and the desire to step out of a normal life’ Eva Dolan

‘It is devious, dark, deliciously chilling. A formidable addition to an accomplished series that just keeps getting better and better’ Never Imitate Blog

Praise for No Other Darkness:

‘Riveting … Sarah Hilary delivers in this enthralling tale of a haunted detective, terrible crime, and the secrets all of us try to keep’ Lisa Gardner

‘At the centre is a queasily equivocal moral tone that forces the reader into a constant rejigging of their attitude to the characters. And did I mention the plotting? Hilary’s ace in the hole – as it is in the best crime thrillers’ Financial Times

‘Sarah Hilary cements her position as one of Britain’s most exciting and accomplished new writers. Complex, polished and utterly gripping, this is a book to make your heart pound’ Eva Dolan

‘The skill of the prose produces a deft and disturbing thriller’ Sunday Mirror

‘Truly mesmerising from its opening page to its thunderous denouement. A haunting, potent novel from a bleakly sublime new voice’ David Mark

‘Heart-breaking … I can’t recommend this highly enough’ SJI Holliday

‘DI Marnie Rome is a three-dimensional character of an emotional depth rarely encountered in the world of fictional cops’ The Times

‘Hilary’s attention to detail is scrupulous, and she is at her absolute best when it comes to marshalling a cast of characters’ Crime Review

‘Marnie Rome is back and Sarah Hilary has knocked it out of the park for us yet again’ Grab This Book

‘Sarah Hilary explores her characters with forensic insight and serious skill’ Live and Deadly

‘A genius at sending the reader in one direction, while pointing clues in another … Totally and utterly recommended’ Northern Crime

‘A masterclass in developing crime fiction series characters’ Crime Reader Blog

Praise for Someone Else’s Skin:

‘An exceptional new talent. Hilary writes with a beguiling immediacy that pulls you straight into her world on the first page and leaves you bereft when you finish’ Alex Marwood

‘I absolutely loved it’ Martyn Waites

‘An intelligent, assured and very promising debut’ Guardian (Best Spring Crime Novel)

‘So brilliantly put together, unflinching without ever being gratuitous … it’s the best crime debut I’ve ever read’ Erin Kelly

‘A slick, stylish debut’ Sharon Bolton

‘Hilary maintains all her characters with depth and feeling’ Independent

‘It’s meaty, dark and terrifying … And Sarah’s writing is glorious’ Julia Crouch

‘There is a moment when it is almost impossible to keep reading, the scene Hilary has created is so upsetting, but almost impossible not to, the story is so hell-for-leather compelling’ Observer

‘It’s written with the verve and assurance of a future star’ Steven Dunne

‘It’s a simply superb read – dark and thrilling’ Sun

‘Detective Inspector Marnie Rome – secretive, brilliant and haunted by a whole host of demons … excellent novel’ Literary Review

‘I think it must be one of the debut novels of next year, if not THE debut novel …’ Caro Ramsay

‘Intelligently and fluently written with a clever plot and an energetic pace … I think Sarah’s onto a winning series and I really look forward to reading the next instalment’ Cath Staincliffe

‘A thinking woman’s whodunit’ Irish Examiner

‘The parallels with Lynda La Plante’s DCI Jane Tennison are plain to see but there is also a bleakness and sense of evil in the novel that sets Rome apart … richly deserves to succeed’ Daily Mail

‘It has such pace and force’ Helen Dunmore

‘A talented new writer who deserves every accolade for such a breath-taking crime novel’ crimesquad.com (Fresh Blood Pick of the Month)

Noah Jake was running late. He grabbed a bagel for breakfast, leaving the house with it held between his teeth, hands free to search for his Oyster card and keys and his phone, which was playing the theme tune from The Sweeney …

‘Jake.’ Remove the bagel, try again. ‘DS Jake.’

‘Shit, mate.’ Ron Carling laughed. ‘You sound like a dirty phone call. What’ve I interrupted?’

‘Breakfast. What’s up?’

‘Not you, by the sound of it. Late night?’

‘The late nights I can handle. It’s the early mornings that’re killing me.’ No luck finding the Oyster card. He had a nasty feeling his kid brother Sol had swiped it. ‘I’m on my way.’

‘The boss wants you in Battersea.’

‘Where, exactly?’

Ron supplied an address Noah recognised. ‘When?’

‘Ten minutes ago. Better get your roller-disco skates on.’

Forty minutes later, the traffic on York Road was being diverted by police accident signs. A snarl of cars ate the streets to either side of Battersea Power Station. Noah walked in its wide shadow, the tilt of its chimneys like stained fingers flipped at a blue sky. Out of commission for years, the power station was sometimes home to film shoots or exhibitions, but empty for the most part. Dan had worked here when it was an art venue, said it made the Tate look like a maiden aunt’s curio cabinet. Now it was being hauled into a new shape, one chimney gone, hobbling the building like an upturned table. Penthouses were on sale at six million, and there was talk of private clubs and restaurants. Noah was going to miss the old power station. Sunset Boulevard with a savage facelift, still slyly smoking sixty a day …

He heard the police tape before he saw it, switching back and forth.

Black smell of scorch marks from the smash site. An SUV had hit an Audi, the impact piling both cars into a concrete wall, taking a lamp post along for good measure.

DI Marnie Rome was with a traffic officer, her red hair tied back from her face, her neat suit the same shade as the gunmetal Audi, bits of which were still being removed. The SUV was gone, just the shape of its shoulder in the wall. ‘DS Jake. Good morning.’

‘Sorry I’m late.’

‘Everyone’s late,’ the traffic officer said, ‘because of this.’

‘How bad is it?’ Noah asked Marnie. ‘Ron said no one died.’

‘Not yet. Four in hospital, two critical. Our eyewitness says a girl walked out into the road.’

No mention of a girl in the early reports online. ‘She’s one of the critical ones?’

‘She walked away. Not a scratch on her, or not from this. The driver of the Audi was lucky. His wife wasn’t. Nor was the passenger in the SUV.’

‘Which two are critical?’

‘Ruth Eaton from the Audi. Logan Marsh from the SUV. He’s eighteen. His dad was driving him home from a friend’s house. Head injuries. It doesn’t look good.’

‘But the girl doesn’t have a scratch? Where is she?’

‘I wish I knew.’

‘So when you said she walked away …’

‘I meant it literally. We need to find her. From the description, she’s at risk of harm. Half-dressed, covered in scratches. In shock.’ Marnie was studying the scars left by the crash. ‘The Audi’s driver is our only eyewitness. Joe Eaton. He’s at St Thomas’s with his wife.’

‘How old was the girl?’

‘Sixteen, seventeen?’ She pre-empted Noah’s next question. ‘Red hair, not blonde. It doesn’t sound like May Beswick.’

Twelve weeks they’d been looking for May. Noah had hoped …

‘This girl’s skinny,’ Marnie said, ‘and half-dressed. No one in Missing Persons matches her description.’

‘It’s not much of a description.’ Twelve weeks was long enough for May to be skinny, and to have dyed her hair. ‘Didn’t he notice anything else about her?’

‘He was trying not to run her down.’

‘I was in a near-miss accident once. A kid ran into the road, after a ball. I hit the brakes in time, just. He got his ball, vanished like that.’ Noah snapped his fingers. ‘I only saw him for a second, but I can still see the freckles on his nose, scabs on his knees. Like a photo. It happened two years ago.’

‘Flashback memory …’ Marnie’s eyes darkened to ink-blue. ‘Perhaps Mr Eaton remembers more than he realises. Let’s find out.’

St Thomas’s smelt the same as always, a squeaky top layer of clean with sour base notes of bodies. Noah breathed through his mouth from force of habit. He and Marnie walked down a corridor where trolleys had left skid marks on the walls, and the floors had a frantic shine, to the room where Joe Eaton was waiting for news of his wife.

Eaton was in his mid thirties, could’ve passed for twenty-eight. Darkish hair. Grey eyes, the left spoilt by a subconjunctival haemorrhage, bleeding into the white. Natty suit ruined by a neck brace for whiplash. A shade over six feet tall. Blank fright on his face when he saw Marnie and Noah.

‘Mr Eaton, I’m Detective Inspector Rome, this is Detective Sergeant Jake. How are you?’

‘Fine.’ He brought his shoulders up. ‘I’m fine. Ruth’s in surgery. They think a ruptured spleen.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Marnie said, ‘but we need to ask some questions.’

‘How’s Logan? I spoke with his dad last night.’ Joe put a hand across his mouth. ‘It sounded bad, worse than Ruth. And he’s just a kid.’

‘We haven’t spoken with Mr Marsh yet. Shall we sit down?’ Marnie drew up a chair, settling her slim frame to face the man.

Joe nodded, following her lead. Noah could smell his stress: stale sweat under CK1; green hand gel from one of the hospital’s dispensers.

‘I was hoping you could tell us about the young woman you saw last night.’

‘She stepped right in front of me. I didn’t have any choice but to swerve. I’d have killed her otherwise.’ He pushed a hand through his hair. Winced. ‘Has she told you what she was doing?’

‘She’s missing,’ Marnie said. ‘We’re looking for her.’

‘You mean she ran off? After the crash?’ He looked stricken, scared rather than angry. ‘She did that and then she ran?’

‘We’re looking for her. You thought she was injured?’

‘She was covered in scratches. But she’s okay, she must be, otherwise how did she run off?’

‘We’d like to go over your description from last night. In case we missed anything.’

‘There’s not a scratch on me, that’s what I don’t get. Just this thing for the whiplash.’ Joe touched the neck brace then put out his hands and stared at them. ‘Even Logan’s dad … We walked away, both of us. But I’m the only one without a scratch to show for it, and I caused the bloody thing.’

Marnie and Noah waited, not speaking.

‘She walked right in front of us. If I’d hit her, she’d be dead. I was doing thirty tops, but that’s enough to kill someone. I had to swerve.’

‘Which direction was she coming from?’ Marnie asked.

‘My left. I suppose that’s … west?’

‘And she was walking east.’

‘There’s an estate on that side of York Road, maybe she lives there? They breath-tested me, I wasn’t over the limit. I’d had a glass of wine with Ruth, but we were eating spaghetti. I was stuffed full of carbs and I’d had two coffees. We’ve got kids. They’re with Ruth’s sister, too little to understand what’s going on with their mum.’

‘How old are they?’ Noah asked.

‘Sorcha’s two. Liam’s ten months. Carrie’s great with them. They love their auntie.’ Joe wiped his eyes, settled his hands on the lip of the table. ‘Okay. The girl, last night? She looked seventeen, maybe a bit younger. Hard to tell because she wasn’t dressed properly, just a man’s shirt, too big for her, white. And her skin was really pale, except for the scratches. She was moving like a wind-up toy. Not fast, but like she wouldn’t … couldn’t stop. Her face was … scary.’ He blinked. ‘She wasn’t going to stop.’

‘Was she calling for help?’

‘No, but her face … It was like she was screaming.’ He grimaced, moving his head as if he wanted to get rid of the image he’d conjured.

‘Mr Eaton.’ Marnie held out a photograph. ‘Was this the girl you saw?’

‘Isn’t this … Mary Beswick?’ He held the photo by its edges. ‘The missing schoolgirl?’

‘May Beswick. Yes, it is.’

Noah held his breath as Joe studied May’s face, but …

‘It wasn’t her.’ Joe handed back the photo. ‘Sorry.’

‘Are you sure? She could have lost weight since this was taken. Dyed her hair, changed her appearance. How tall was the girl you saw?’

‘Shorter than Ruth. Five foot? Not much more than that. Just a kid, a teenager. Maybe she’s nearer to fifteen. And really skinny. Bony knees. Red hair.’ A glance at Marnie. ‘Not like yours. Red red, like paint.’ His eyes flicked back, frowning, to the photograph. ‘It was dyed.’

‘Long hair, or short?’

‘To her shoulders. But it was crazy, like she’d back-combed it. Really wiry and wild.’

May Beswick was five foot one, not skinny but not fat. In the photo, her blonde hair was waist-length, brushed smooth. She wore a green jumper over a white blouse, and she was smiling, her top lip coming away from her front teeth, soft brown eyes crinkled at the corners. Noah didn’t need to look at the photo to be sure of those details. He’d been seeing her face in his sleep for twelve weeks.

‘What else was she wearing,’ Marnie asked, ‘apart from the shirt?’

‘Nothing. Knickers, I think.’ Joe flushed. ‘No trousers, no shoes. No bra. Maybe she was seventeen. I can’t tell. She should’ve been wearing a bra.’

Somewhere a door slammed open. Joe turned his head towards the sound. His hands were clenched on the table, his neck red inside the brace.

Marnie said, ‘Tell us about the scratches.’

‘All … all over her. Her legs, her stomach, her chest.’ He grimaced. ‘Everywhere.’

In the photograph, May’s face was smooth, like her hair. Round cheeks, a wide forehead, no acne. Not a mark on her, twelve weeks ago.

‘Was her face scratched?’

‘Not her face. But everywhere else, from what I could see.’

‘Were the scratches recent?’ Noah asked.

‘I don’t think so. Hard to tell in the headlights, and I only saw her for a second. They looked black, not red, not like fresh blood.’ He drew a breath. Held it in his chest. Let it go. ‘Ruth got a better look than I did. The girl came from the left, her side of the car. If …’ He pushed his hands at his eyes. ‘When she wakes up, she’ll be able to give you a better description. Ruth always notices stuff. She’s brilliant like that.’

He pushed harder with his hands, knuckles bleaching under the pressure. ‘I can’t forget her face. Maybe it was May Beswick, I don’t know. She didn’t look like her, but she didn’t look like anyone. Whatever happened to her … she looked … terrorised.’

He dropped his hands and looked up at Marnie and Noah. ‘She wasn’t making a sound, not a sound, but her whole face was screaming.’

Three months ago, I thought I was safe. Home and dry, off the streets. And not just me. All of us thinking the same thing, that we’d landed on our feet. Like cats. He took us all in.

He called the new place home, but not the way you’d think. ‘It’s wide open,’ he said.

Open-plan, the estate agent called it, but Harm meant something different, the sort of place where you’re overlooked, where you disappear even if you don’t mean to. London’s full of places like that. Dead spaces, dazzle spots. Empty doorways, gaps between buildings. Places no one thinks of looking because they don’t see, not properly. Maybe they did once, but they’ve trained themselves to stop. Even when you’re right where they walk every morning, when your hand’s out and you’re asking for a little help, even when you’ve got a fucking dog. A thing could be right in front of your face, Harm said, and you still wouldn’t see it. Some things are just … invisible.

Grace wouldn’t be invisible. She’d started answering back. She wasn’t playing by the rules and I wanted her to shut up. Too much fizz in her, making her skip, making that crazy red hair stick out like she’d rubbed a balloon the wrong way. She wouldn’t sit still and she wouldn’t shut up, and I thought there was something wrong with her. Something was wrong with each of us, that was how he chose us. The noisy ones like Grace and the ones like me who were disappearing – burning up like fireworks until nothing was left.

Harm would keep us safe, he said. We just had to listen to him, let him help us. Grace should’ve shut up. At least she had a roof over her head.

A new roof. The house where he’d been keeping us was getting too small, too much like a squat. We were spilling over, making mess. This new place was better. ‘Great potential,’ Harm said.

The estate agent liked that. ‘Some people just see dead space, but I can tell you’re one of the smart guys.’

Harm nodded, and turned his back. He thought the man was a cocksucker, I could see it in his face. Harm hates cocksuckers; it was one of the first things I found out about him.

The new place was a flat, but on two floors. Split-level, the estate agent said, loft living. One room higher than the others, up a flight of stairs. My room. Unfinished when we saw it that first time. Raw walls with fist-sized holes for wiring, and the estate agent was full of crap about uplighting and underfloor heating, but you could see the money they’d have to pour into the place just to get it fit to live in. No wonder it ran out. It looked good, though, back then. The cocksucker left us to appreciate the view. All of London dazzling under us. ‘I’ll give you a minute,’ he said.

Harm turned his back.

So you know, that’s when he’s dangerous – when his back’s turned. It means he can’t stand looking at you any longer. You’ve made him sick, angry. So sick and angry he won’t look at you. He wants you to stop talking, stop looking, stop being. We all knew this, even Grace, but the estate agent didn’t. He was the sort of man who used to sidestep me when I was begging on the streets, so I suppose I wanted him to stop talking and stop being, just the same as Harm did.

In the end, Harm shook the man’s hand, making his eyes light up, smelling a sale. That was back before the money ran out, when they still believed the uplighting and underfloor heating would happen. Back before Grace stopped fizzing. Before he made her stop.

I remember exactly how it felt, that first day in the new place.

The others followed Harm and Christie outside, but I stayed, wanting to get my bearings, needing to know what I was up against.

Harm doubled back. I didn’t hear him on the stairs, but I saw dust smoke up from the floor when his feet moved across it, not making a sound.

Then the heat of him behind me …

The damp weight of his shadow across my shoulders, at the back of my neck.

He kept my hair cut short. I could feel his stare sharp on my skin.

Not touching. He never touched. It was worse than that.

His stare was hotter than fingers, or a tongue.

I could smell him, smiling.

He was so heavy behind me.

‘This is it,’ he whispered. ‘This is home.’

Like Joe Eaton, Calum Marsh had a neck brace and a sling for his right arm, taking the strain off a badly bruised collarbone. He was sitting on the end of the hospital bed, trying to push his left foot into a leather shoe. Whoever had removed his shoes hadn’t untied the laces, and he was struggling, his face fisted in concentration. Wearing chinos and a half-buttoned shirt, wanting to be dressed so he could go and check on his son. All his panic and pain was there in the struggle with the shoe.

‘Mr Marsh, I’m DI Rome and this is DS Jake.’ Marnie crouched and took the shoe, freeing the laces from the stranglehold of a knot. ‘We’re here to find out what happened.’

Calum peered at her in confusion. ‘Have you seen him? Logan?’ His feet and face jumped with stress. ‘I was asleep. Is his mum here?’ Looking away from Marnie, concentrating on Noah. ‘Is he okay? What’s happening?’

‘We’re waiting to speak with the doctor. Logan’s in surgery.’ Marnie stayed crouched, the unlaced shoe in her hands. ‘I’ve asked someone to speak with you as soon as there’s news.’

‘There’s nothing I can do. That’s what they said in the ambulance. And here. The nurses said the same.’ Calum wiped his hand on the sheet, leaving a rust stain where his sweat had brought dried blood back to life. ‘There’s nothing.’ He was in his early forties, well-built, greying temples and stubbled skin, blood in the lines under his eyes. Unless the shirt was hiding damage that Noah couldn’t see, the blood was his son’s.

‘There should be news soon.’ Marnie put the shoe down and straightened, stepping back. She nodded at Noah, who moved a chair to the side of the bed.

‘We were talking with Joe Eaton about how it happened,’ he said. ‘We’re trying to find the girl.’

‘The girl.’ Calum’s face was empty. He blinked, focused. ‘What girl?’

‘The girl who walked out into the road. That’s why Joe Eaton swerved.’

‘He came right at me.’ Calum put his hand up, palm out. ‘Right at me.’ His hand was broader than Joe’s, and scarred in places, twitching with shock like the rest of him.

‘Joe says a girl walked in front of the Audi.’ Noah took care not to crowd the man. ‘That’s why he swerved. To avoid hitting her.’

‘That’s what he said? The other driver … He said there was a girl …?’

‘You didn’t see her?’

‘No girl, just the Audi coming at us, and … the wall. Then Logan hitting the windscreen, making this noise.’ Punishing his injured arm with his left hand. ‘His head made this noise like something bursting. He broke the windscreen with his head …’ Putting his hand out, blindly. ‘Don’t let him die. Not like this. Not my fault, don’t let it be my fault, he’s just a kid. My kid.’

‘All right.’ Noah took the man’s hand, chilled and sticky with his son’s blood, aftershocks locking and unlocking the fingers. ‘Mr Marsh? Calum. It’s all right.’

Marnie left, coming back with a nurse, who helped Logan’s dad back into the bed. Noah waited until he was lying down before easing his hand free from the man’s grip.

‘Sorry,’ Calum kept saying, to the nurse, to Noah. ‘I’m sorry.’

Marnie was in the corridor, waiting.

‘He didn’t see a girl,’ Noah said. ‘Do you think Joe Eaton got it wrong?’

‘Something made Joe swerve. He wasn’t drunk and it wasn’t raining. Traffic conditions were good. Why invent a girl? Especially a half-dressed girl covered in scratches.’

She took out her phone. ‘We need to know who else was on that road. DC Tanner’s looking at CCTV. Whether or not she’s May Beswick, this girl’s in trouble.’ She dialled a number, held the phone to her ear. ‘Ed, call me when you get this. I need to pick your brains.’

Ed Belloc was a victim care officer, one of the best. He and Marnie had been together six months, maybe a little longer.

‘Whether or not she’s May Beswick,’ Noah repeated. ‘You think there’s a chance it’s her?’

‘I don’t know. I’d like to hope so. At least … This girl was running from someone. Injured by the sound of it. She didn’t stop after causing the crash. I’m wonderin. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...